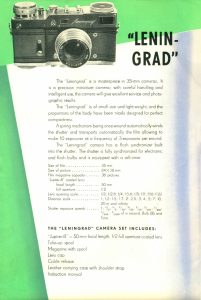

This is a Leningrad 35mm rangefinder camera made by Gosularstvennyi Optiko-Mekhanicheskii Zavod (GOMZ for short) between the years of 1956 and 1968. Although using the same M39 screw mount as many other Soviet rangefinders, the Leningrad is not based off any existing German design like the Zenit or FED rangefinders that share the mount. The Leningrad is named after the city of the same name (now St. Petersburg) which GOMZ was based out of. It is considered by many to be the most advanced and ambitious of all Soviet made rangefinders. Featuring a wind-up clockwork film advance, it can shoot up to 20 exposures on a single wind of the large knob on top of the camera. It’s rangefinder uses a very unique system of prisms instead of beam splitters, that shows a very bright and precise combined image. Using the M39 lens mount meant the camera could be used with a huge number of excellent German, Japanese, and Soviet screw mount lenses.

This is a Leningrad 35mm rangefinder camera made by Gosularstvennyi Optiko-Mekhanicheskii Zavod (GOMZ for short) between the years of 1956 and 1968. Although using the same M39 screw mount as many other Soviet rangefinders, the Leningrad is not based off any existing German design like the Zenit or FED rangefinders that share the mount. The Leningrad is named after the city of the same name (now St. Petersburg) which GOMZ was based out of. It is considered by many to be the most advanced and ambitious of all Soviet made rangefinders. Featuring a wind-up clockwork film advance, it can shoot up to 20 exposures on a single wind of the large knob on top of the camera. It’s rangefinder uses a very unique system of prisms instead of beam splitters, that shows a very bright and precise combined image. Using the M39 lens mount meant the camera could be used with a huge number of excellent German, Japanese, and Soviet screw mount lenses.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 50mm f/2 Jupiter 8 coated 4-elements

Lens Mount: M39 Screw Mount

Focus: 0.9 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Combined Split Image Coupled Rangefinder w/ Multiple Focal Length Frame lines

Shutter: Cloth focal plane

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Coldshoe and 5 – 25ms adjustable delay Flash Sync

Weight: 990 grams (w/ Jupiter 8 lens)

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/russian_pdf/leningrad.pdf

How these ratings work |

The GOMZ Leningrad is an extremely fascinating and feature rich camera built by a country not exactly known for innovation. It is considered by many as not only the most ambitious Soviet camera ever made, but it has one of the most distinct looks and feature sets of any camera made by any country. With a motorized film transport capable of up to 3 fps, a very bright and unique prism based combined image rangefinder, and support for the M39 lens mount, if there was one Soviet camera to add to your collection, this is it! | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 30% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 11.7 | ||||||

History

The former Soviet Union is known for a great many things, Communism, the first man in space, the Soyuz spacecraft, vodka, and cameras. Since you’re reading my site, it’s likely you’re interested in that last thing, cameras.

The earliest Soviet optics factory actually predates the Soviet Union itself. Formed in 1914 in the city of Petrograd (now St. Petersburg) the Russian Joint-Stock Company of Optical and Mechanical Production opened, building early optics products such as rifle scopes during the first World War. Over the next 20 years, this factory would change names several times and experience many changes in leadership. In 1924, Petrograd would be renamed Leningrad, and the factory would go through a series of name changes, from GOZ, TOMP, VTOMP, VOOMP, and eventually Gosularstvennyi Optiko-Mekhanicheskii Zavod, or GOMZ for short.

In it’s earliest years, GOMZ produced various folding sheet and roll film cameras based heavily off German designs. One of it’s most successful early designs was a 9×12 folding bed camera called the Fotokor-1 which was produced from 1930 through 1941. During the 1930s, GOMZ was the Soviet Union’s primary maker of medium format cameras, but they also dabbled in 35mm design.

Many people think that the Soviet FED rangefinder produced in Kharkov, Ukraine was the first Soviet Leica inspired 35mm rangefinder, but it was actually the Leica II inspired Pioneer made when GOMZ was still called VOOMP between 1933 and 1937. Less than 1200 VOOMP Pioneers were produced before production ended. By this time, the FED Labour Commune was already up and running churning out large numbers of FED rangefinders.

FED was basically a military type school that was designed as a youth rehabilitation center. The center was created by Anton Makarenko who was a Ukrainian educator who believed that troubled youths could be productive members of society by combining education and labor in a strict atmosphere. The center itself was named after Felix Edmundovich Dzerzhinsky who was the founder of the Soviet Union’s secret police, known as the NKVD. The NKVD was the predecessor of the much more well known KGB.

Over time, FED would improve both the design and the reliability of the camera, but unfortunately, it’s location in Ukraine meant it was more prone to damage to German fighters in World War II. Anticipating imminent destruction, in 1942 the Soviet government transported much of the FED factory’s machinery to the city of Berdsk, Siberia for safe keeping. Plans for the FED camera were given to another Soviet optics factory called Krasnogorsk Mechanical Works or KMZ for short in Krasnogorsk, near Moscow where they eventually started producing their own copy of the FED, which they branded the Zorki.

Due to severe damages at the FED factory during the war, both KMZ and the nearby GOMZ factory in Leningrad, Russia would be the first Soviet optics factories to resume camera production after the war. Although not up to the same high standards as the German Leicas that both the FED and KMZ Zorki’s were based off, the post-war cameras were dramatically better than early pre-war models. The Zorkis and FEDs would sell well within the Soviet Union and by the 1950s would begin to be exported to other European countries and even to the United States.

GOMZ benefited from the Soviet Union’s occupation of East Germany after the war where various German optics factories were dismantled and shipped to various locations within the Soviet Union. As a result, in 1946 GOMZ was able to quickly start production on a new camera called the Komsomolets which was very similar to the Voigtländer Brillant “pseudo-TLR”. The Komsomolets was the first all new camera to start production in the Soviet Union after the war. It would receive various revisions throughout it’s life including a name change in 1949 to the Lubitel.

The Lubitel was an extremely popular camera in both the Soviet Union and export countries as it was lightweight, small, cheap, easy to use, and produced better than average photographs. The original model would remain in production until about 1988, and in 2008 would be re-released by a new company as the Lubitel Universal 166+ which is still in production to this very day.

With the success of the Lubitel, the GOMZ factory was able to expand, releasing several new, and increasingly competitive designs. It’s first post war 35mm camera was the Smena which started production in 1953. A simple and compact 35mm scale focus camera with an entirely Bakelite body, the Smena would launch an entire family of compact point and shoot 35mm compact cameras that would exist up until after the fall of the Soviet Union in the 1990s.

After the Smena however, the engineers at GOMZ decided to reach for the stars and design what would eventually become the first Soviet made 35mm camera built for the professional photographer. GOMZ’s new camera would use bits and pieces of an earlier Soviet prototype called the GOI from the 1940s and would go through various revisions until it’s eventual release in 1956. The new camera boasted an innovative feature set and high build quality that exceeded all previous Soviet designs. Named after the city which it was built in, the GOMZ Leningrad was the crowning achievement of the Soviet camera industry up until that point.

With the exception of the M39 Leica Thread Mount shared by the KMZ Zorki and FED rangefinder, the Leningrad had a long list of unique features like a wind up clockwork film transport that was said to be able to fire the shutter as fast as 3 frames per second. It had an unusually large and bright combined image rangefinder and viewfinder which used prisms instead of mirrors or beam splitters to project an accurate rangefinder image for easy focusing. The viewfinder had automatic parallax correction and always showed frame lines for 35mm, 50mm, 85mm, and 135mm lenses.

The rubberized silk coated focal plane shutter had speeds from 1 second to 1/1000 making it competitive with nearly every other German or Japanese rangefinder produced at the time. It offered adjustable flash synchronization, had an accessory shoe, a kickstand to balance the camera on a flat surface, and supported all standard Eastman film cassettes.

Although originally sold in the Soviet Union, the camera was often exported to other countries not only to help with sales, but also to show the world that the Soviet Union was capable of a world class professional quality camera. In the November 1958 issue of Modern Photography, editor Herbert Keppler wrote an article pondering how good two new Russian cameras were. He used a Canadian importer from Toronto and bought two Russian cameras, the first was the Zenit-C SLR and the second, the Leningrad.

Listed with a retail price of $289.50 in Canadian dollars, I can’t really say how that compares to US Dollars today as historical foreign currency conversions are notoriously inaccurate, but I feel confident in saying that this would compare to well over $2000 in today’s money, making the Leningrad a very expensive camera. Adding to the suspicion the western world must have had in Soviet made products, I can’t imagine many were sold here.

Herb Keppler gave the camera a mixed review saying the Jupiter 8 lens had a rough build quality and was soft wide open. He said that although the prism viewfinder was large and bright, the combined rangefinder patch was difficult to use when there was no vertical lines in the viewfinder. He said that shutter speeds below 1/100 were difficult due to vibrations caused by the shutter firing. He didn’t care at all for the difficult to remove film back and poor design of the rewind mechanism.

It wasn’t all bad though. Keppler found the camera comfortable to hold and enjoyed the angled grip on the camera’s left side. He appreciated the motorized film transport that he said was capable of 12 shots in 6 seconds, and said the camera experienced no malfunctions during his month-long test. His overall verdict however, was that based on these two cameras, the Russian camera industry still had a long way to go before it could catch up with the West.

The Leningrad would remain in production for nearly 12 years, but with only 76,000 ever sold, sales were quite slow. With only a few minor cosmetic updates, the Leningrad would remain mostly unchanged throughout it’s entire run. In 1961 an updated Leningrad model was announced that was said to have a built in light meter, but no example has ever shown up, suggesting it was never produced.

GOMZ would change it’s name to LOMO in 1962 and continue to release a dizzying array of new and increasingly small and inexpensive cameras. Some Leningrads exist from after the company was renamed and are branded as LOMO Leningrads. In 1975, a model called the LOMO 135BC would have a motorized film transport like the Leningrad, but would otherwise be a simple scale focus fixed lens camera.

LOMO still exists today as a maker of various optical goods but more significantly, inspired something called the Lomograpic Society which is entirely unrelated to the Russian company it’s name is based off. Lomography is an unofficial name for a photography movement wherein people use inexpensive cameras with cheap plastic bodies and simple one and two element lenses to shoot imperfect photography.

Today, the GOMZ Leningrad is considered by many to be the pinnacle of the Soviet camera industry and remains one of the most collectible Soviet cameras ever made. It’s unique, highly quirky all Soviet design, and innovative list of features separate it from the endless German Leica and Contax clones often associated with Soviet cameras. Since only 76,000 were ever made, and even fewer exported to countries like the United States, finding one today, especially in working condition can be difficult. If you are looking to add one of these fascinating cameras to your collection, your best bet is to scour eastern European and former Soviet eBay sellers looking for one that’s been serviced. It won’t be cheap, but it just might be worth it!

My Thoughts

The GOMZ Leningrad is a fantastic camera. Before handling one, I knew this was one I wanted to get my hands on. I had unsuccessfully bid on several over the years, but a combination of rarity in the US, high shipping costs from eastern Europe where these things are more common, and their reputation for being less than reliable without a CLA, I was unable to find one in a price range that I was willing to pay.

That was until one day this past spring when I made the long voyage to the frozen north suburbs of Buffalo Grove to visit one of the largest collections of Soviet cameras in the world. Vladislav Kern is the proprietor of this basement museum and is both the owner of the USSRPhoto.com website and the Vintage Camera Collectors Facebook group.

An emigrant of the former Soviet country of Georgia, Vlad’s collection of Soviet cameras, lenses, and other gear rivals that of any collection I’ve seen, regardless of make. Thankfully after agreeing to sign away my first born, Vlad allowed me to borrow a few examples from his collection for review. So of course the first model that I targeted was this nice looking Leningrad.

Weighing a not-insignificant 990 grams with the Jupiter 8 lens, the Leningrad is a large and heavy piece of Soviet metal. The camera has a unique shape with a prominent angular grip on the camera’s left side (with the camera to your eye) meaning you can keep secure hold of the camera while winding the large knob on the cameras top plate.

It’s that knob that for me is the camera’s most interesting attribute. In the last year, I’ve become somewhat of a fanboy of other clockwork wind-up cameras like the Kodak Motormatic 35, Fujica Drive, and Robot Junior.

Each of these cameras has some type of large wind-up knob that puts tension on the film transport and shutter to automatically advance the film and cock the shutter after each previous exposure, making the camera ready for it’s next shot. It was this motorized film transport that gave mechanical cameras early versions of rapid fire shutters. If you have a fast enough trigger finger, you could in theory fire off as many as 3 exposures per second. Although not as fast as modern digital cameras that can burst shots sometimes as high as 10 frames per second, this high speed shutter release was still considered pretty fast for the 1950s.

The top plate shows the angled corner of the left side giving you an idea of what it’s like to hold the camera. From left to right is a dual film reminder dial and rewind knob, accessory shoe, shutter speed selector, Instant/Bulb shutter selector, shutter release, exposure counter, and wind knob. The film speed dial has numbers conforming to both the DIN and Soviet ГОСТ (GOST) scale. The GOST scale uses an arithmetic numbering system which was similar to the ASA scale, differing only by a factor of 0.1 so for example, GOST 90 is the same as ASA 100, 180 is 200, and so on.

On the side of the camera, below the wind knob are the numbers 5 through 20. These numbers are used for an adjustable 5 to 20ms delay when using flash photography. There is a movable slider just beneath the winding knob that increases the delay between when the flash is triggered based on whatever different types of flashbulbs you are using. The English language manual for the Leningrad strangely doesn’t mention how this works, but I have to imagine that somewhere is a chart explaining which delay setting should be used for various flashbulbs that existed at the time of this camera’s release.

The back of the camera has a surprisingly large eyepiece for the viewfinder. While not as large or bright as a Leica M3, the Leningrad’s viewfinder is significantly larger than those found on other 35mm Soviet rangefinders like the Kiev 3/4, FED 2, or early Zorkis. There is a knurled metal ring around the eyepiece which can be unscrewed slightly which acts as a diopter adjustment to compensate for people with poor vision. If you unscrew this ring too far, it will detach from the camera, so be careful. Immediately below the wind knob on the back is a reset slider for the exposure counter.

The viewfinder of the Leningrad is one of the most unique I’ve ever seen on any camera ever. For starters, the viewfinder does have automatic parallax correction, but rather than move the frame lines like most rangefinder cameras, the entire image moves as you reach close focus. Second, the rangefinder uses a prism instead of mirrors and beam splitters like many rangefinder equipped cameras use, but that’s not the most unique part.

Like most 35mm rangefinders, there is a smaller rangefinder patch in the center of the viewable image, but unlike other 35mm rangefinders, the image is not a “coincident” image in which a second image is projected over the main image. In the Leningrad, the rangefinder image entirely blocks out the center of the main viewfinder image. This means, you cannot see through the rangefinder image, rather, it is an entirely new image, but coming through the rangefinder window. This might be difficult to explain in words, but if you look at the image to the right, I have the rangefinder intentionally out of focus, so you can see the difference of the center image compared to everything around it. Notice how you cannot see the middle part of the light pole, but rather see the tree trunk of the tree to the left. The center portion of the light pole is off the right, indicating the image is not in focus. Had I taken a second shot of the viewfinder correctly lined up, the light pole would have smoothly transitioned from the viewfinder image, to the rangefinder image, and then back out to the viewfinder image.

The advantage to this is that the rangefinder image is as bright and clear as the rest of the image around it. There is no tinted color like in most rangefinder cameras, making it really easy to see. The downside of course is that since there is no “double image” you cant see that part of the viewfinder when things are out of focus making scenes without vertical lines difficult to accurately focus. In addition to the rangefinder window, there are projected black viewfinder frames for 135mm, 85mm, and 50mm. Although I don’t know for sure, I can guess that the entire visible viewfinder beyond the 50mm frame corresponds to a 35mm frame.

The bottom of the camera requires a little more explaining than the typical bottom of most cameras. From right to left, we have a rather standard locking ring for the film back. This works like most 35mm rangefinders of the 50s in which a knob opens and closes reloadable “Leica” cassettes. In the center is a 3/8″ tripod socket surrounded by a balancing foot that when flipped out, helps keep the camera level on a flat surface without falling forward on the lens.

On the far left is an outer ring which must be used in tandem with the locking ring on the right to remove the back of the camera. Simply rotating the locking ring 180 degrees like on a Nikon rangefinder is not enough to open the camera. You must rotate this counterclockwise several times to release it. In the center of this outer ring is rotating button with a metal knurled pattern which you must press in while rotating to release the tension on the clockwork drum inside of the camera so that you can rewind the film into the camera. Without doing this, trying to rewind the film is impossible as the drum will maintain tension on the film, possibly tearing it. It is super important that after unloading film and loading in a new roll, that you remember to reset this button to put tension back onto the drum, as you wont be able to properly advance the film.

With the back removed from the camera, you see what looks like a normal 35mm camera, but instead of a take up spool, has a large chrome drum on the right side, but after staring long enough, something is missing. Can you see it? I’ll give you a second before telling you.

Okay, its been a second, you’ll notice that unlike pretty much every mechanical 35mm camera ever made, there are no sprockets anywhere in the film compartment. Mechanical cameras rely on those sprockets to detect how much film travels after each exposure. This is important to know as this affects the frame spacing as you shoot more exposures on a roll. The drum is designed to rotate exactly half way each time you press the shutter release. This is good for a full exposure at the beginning of a roll of film. As you get closer to the end of a roll, especially 36 exposure rolls, because more film is wrapped around itself, the diameter of the spool/drum increases, which also increases frame spacing on your film. Without the ability to detect how much film has traveled, the frame spacing varies from the beginning to the end of a roll of film.

The Leningrad’s drum only has a slit on one end that’s too small for the leader normally found on modern 35mm film. I do not know if older Soviet film had a different leader, but I had to trim about 5mm of the width in order to attach a normal 35mm leader to the drum. Make sure you have the rewind button in the correct position in order to properly advance the film to secure the film to the drum. Once you’re sure that the film is properly attached, replace the back of the camera and lock it into position.

The Leningrad uses a standard 39mm lens mount so replacing the lens is as simple as getting a secure grip on it and rotating it counterclockwise to remove and clockwise to reattach. Sadly, not every M39 lens will attach to the Leningrad as a result of the protruding top plate. If you look at the image to the right closely, you’ll see that the chrome lens mount ring is recessed slightly behind the bottom of the top plate. This means that many Japanese and German M39 lenses like the Canon 50mm f/1.4 and Voigtländer Ultron 35mm f/1.7 won’t fit. Compatibility with non Soviet lenses was likely not a priority for the engineers at GOMZ, but I have to believe there are at least a few Soviet lenses which didn’t fit either.

The front of the camera has a standard PC flash socket for flash photography. To the left of the lens mount is a metal self-timer lever that can be used to release the shutter after up to a 10 second delay. The Leningrad being reviewed here is an earlier variant with two screws to the right of the lens mount. Later Leningrads have four screws, two on each side of the lens mount.

Without a doubt the most notable feature of the Leningrad is the motorized film transport, but it’s also the camera’s weakest link. With film loaded in the camera, there is absolutely no way to know if the film is transporting correctly. If the leader becomes detached from the drum, the camera will continue to wind and fire like normal. The rewind knob does not rotate during normal film transport like most mechanical cameras letting you know its properly loaded.

Another downfall of the design is that in the (very) likely event the film transport gets jammed, there is no way to manually advance it to the next frame to continue shooting. A trick that is discussed on a number of camera related sites is that sometimes if after firing the shutter, the film transport doesn’t work, you can relieve tension on the shutter by gently rotating the shutter speed dial counterclockwise, and then letting it go to snap back into position. This action can sometimes release a jammed shutter, advancing the film for the next shot. If this doesn’t work however, you have no other option than to rewind the film back into the cassette and open the camera.

The Leningrad was an entirely unique design in which nearly every element of the camera, save for the lens mount, was designed exclusively for this camera so it borrows nothing from existing, proven designs. This obviously gave it an edge over more mundane Soviet cameras that borrowed quite a bit from existing German designs, but also made it less reliable. It is said that later Leningrads are more reliable as they were produced after the company had worked out some design quirks, improving reliability. Whether this is true is anyone’s guess, but even if it is, the newest Leningrads are still 50 years old, and no camera is exempt from the perils of time.

My Results

I had trouble with the film transport on the Leningrad as my first attempt at shooting it, the shutter fired twice before jamming. As mentioned earlier, you can attempt to un-jam it by relieving tension using the shutter speed selector, but that didn’t seem to work. I rewound the film and reloaded it twice and the problem came back both times. Each time I inserted the film into the camera, the leader became more and more mangled so I trimmed it each time. After realizing that perhaps the issue was with that particular roll of film, I decided to try a second roll of Fuji 200 and that seemed to do the trick as it loaded and advanced correctly. Not knowing how long my luck would last, I took the camera on a trip to visit family in Northern Michigan and fired off nearly the entire roll over the course of 2 days.

Although the loading experience of the Leningrad was quite stressful, once the film was transporting correctly, the camera performed reasonably well with only the occasional hiccup. The bright combined image rangefinder was easy to use in bright light and in scenes with lots of vertical edges, but like Herb Keppler mentioned in his review from 1958, in scenes without a lot of clear lines, it was a bit difficult to use.

This is the 4th Soviet camera that I’ve used with a Jupiter 8 lens, so the results were about as I expected. Shot wide open, the images are soft, but once you stop it down even 1 stop, sharpness improves, giving nicely rendered and sharp images without any noticeable lens anomalies like chromatic aberrations or vignetting. Even the bluish lens coating performed well as I saw no signs of glare in any images I shot, and color reproduction was quite faithful to how I remember the scenes being in person.

The GOMZ Leningrad is a fascinating camera. I love it’s design, looks, and even though it’s not as useful as I had hoped, the large and bright viewfinder was much easier to use than other Soviet rangefinders like the FED 2 or early Zorkis.

The camera acted up a couple of times requiring me to waste a shot to get the film advance to work, but that’s OK. This particular example was an early version and was built at a time where innovation often came at the expense of long term reliability.

Of all the cameras I’ve recently borrowed from various collectors, this one was the one I was saddest to see go home. Even though it wasn’t perfect, I let Vlad know that if he ever comes across another, in good working condition, and for a bargain price, to let me know!

Additional Resources

http://www.sovietcams.com/index.php?-398124798

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Leningrad

http://corsopolaris.net/supercameras/leningrad/leningrad.html

https://www.lomography.com/magazine/1556-lomo-plc-leningrad-staff-review

http://www.commiecameras.com/sov/35mmrangefindercameras/cameras/others/index.htm

http://ussrphoto.com/Wiki/default.asp?WikiCatID=12&ParentID=1&ContentID=75&Item=Leningrad

http://photoethnography.com/ClassicCameras/Leningrad.html

https://www.rangefinderforum.com/forums/showthread.php?t=116868

That’s a crazy fun viewfinder. I’ve had quite a few old Soviets, but never one of these. As per usual, it looks as it can double for use as a weapon from its heft. Great write-up.

Thanks Kevin! It is definitely “personal defense worthy”! 🙂

Thank you Mike for your very thorough and detailed examination of this camera. I visit your blog to experience old cameras vicariously, without the expense of buying them, so I’m very grateful for your generosity!

Gran revisión, se agradece para poder entender mejor mi “nueva” Leningrad. Gracias