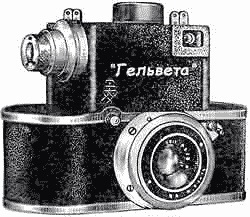

This is the Sport (Спорт), a 35mm Single Lens Reflex camera made by Gosudarstvennyi Optiko-Mekhanicheskii Zavod (GOMZ for short) near Leningrad, Russia between the years 1935 and 1941. The GOMZ Sport is an evolution of an earlier prototype camera called the Gelveta. The GOMZ Sport is credited as the Soviet Union’s very first 35mm SLR and one of the earliest made by any company, being narrowly beat to the market by the Ihagee Kine Exakta. Although a true single lens reflex camera, the GOMZ Sport has quite a few differences from later SLRs, namely the waist level optical viewfinder, unique vertically traveling guillotine focal plane shutter, and a unique bayonet lens mount to which no other lenses were ever made.

Film Type: 135 (35mm), 50 Exposures in Special Cassettes

Lens: 5cm f/3.5 Industar-10 uncoated 4-elements in 3-groups

Lens Mount: GOMZ Sport Bayonet

Focus: 1 meter to Infinity

Viewfinder: Eye Level Reflex Viewfinder with Optical Eyepiece and Scale Focus Optical Viewfinder

Shutter: Vertically Traveling Guillotine Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1/25 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Other Features: None

Weight: 736 grams, 644 grams (body only)

Manual: None

How these ratings work |

The GOMZ Sport was the first Soviet 35mm SLR and second ever to go on sale in the world. It has a design that is much different from SLRs from later in the 20th century, but otherwise works similarly to them. The reflex viewfinder cannot be used at waist level and requires the camera to be held to your eye, but is brighter than expected. The shutter is a clever design and the Industar lens is capable of above average image quality, meaning that when examples of this camera are found in working condition, makes really nice images. The GOMZ Sport is a rare camera and hard to find today, but if you can find one, makes for an excellent addition to your collection. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 40% | |

| Bonus | None | ||||||

| Final Score | 12.6 | ||||||

History

The earliest Soviet optics factory actually predates the Soviet Union itself. Formed in 1914 in the city of Petrograd (now St. Petersburg) the Russian Joint-Stock Company of Optical and Mechanical Production opened, building early optics products such as rifle scopes during the first World War. Over the next 20 years, this factory would change names several times and experience many changes in leadership. In 1924, Petrograd would be renamed Leningrad, and the factory would go through a series of name changes, from GOZ, TOMP, VTOMP, VOOMP, and eventually Gosularstvennyi Optiko-Mekhanicheskii Zavod, or GOMZ for short.

In its earliest years, GOMZ produced various folding sheet and roll film cameras based heavily off German designs. One of it’s most successful early designs was a 9×12 folding bed camera called the Fotokor-1 which was produced from 1930 through 1941. During the 1930s, GOMZ was the Soviet Union’s primary maker of medium format cameras, but they also dabbled in 35mm design.

Many people think that the Soviet FED rangefinder produced in Kharkov, Ukraine was the first Soviet Leica inspired 35mm rangefinder, but it was actually the Leica II inspired Pioneer made when GOMZ was still called VOOMP between 1933 and 1937. Less than 1200 VOOMP Pioneers were produced before production ended. By this time, the FED Labour Commune was already up and running churning out large numbers of FED rangefinders.

Around the same time the GOMZ factory was about to release its new Leica inspired rangefinder, the company set their sights on something higher, the world’s first 35mm Single Lens Reflex camera.

SLRs were not new, as various medium and large format reflex cameras had been around since the late 1800s. These early SLRs were very large, bulky, rarely had interchangeable lenses, and had very dim viewfinders, but offered the rare benefit of being able to “see focus” by composing your image through the taking lens. Models by Eastman Kodak, Folmer & Schwing, Voigtlander, and Zeiss often featured focal plane shutters with fast top speeds, and were favored by portrait photographers who wanted precise control over depth of field and the ability to closely focus on their subjects.

With the release of the Leica rangefinder in the 1920s, more attention was placed on 35mm film cameras, but no one had yet attempted to make a 35mm reflex camera. History would tell us that the first company to market a successful 35mm SLR was Ihagee Kamerawerke in Dresden, Germany when they released the first “Kine” Exakta in 1936, but work on a Single Lens Reflex concept began much earlier in 1929 with a conceptual camera designed by Soviet inventor A.A. Min. No images or physical examples of Min’s camera have ever been found so it is not known how far beyond the design phase it ever made it. A drawing in Jean Loup Princelle’s “The Authentic Guide to Russian and Soviet Cameras” shows a camera in the shape of a rectangular cube, with a round viewfinder sticking up through the top plate of the camera, a traditional lens in the center, and various knobs and buttons on the top and side, possibly functioning as a film advance and shutter release.

The camera would have a focal plane shutter capable of 8 speeds and was stated to use double perforated 35mm “kine” film, making seventy-five 24mm x 32mm exposures per roll. Princelle further describes the camera as having a reflex mirror that created a light tight box, eliminating the need for a dark slide when advancing the film to prevent light leaks, a pressure plate that retracted while advancing film, and some type of film notching device, perhaps used to identify the end of exposed film for mid roll changes.

Whether Min’s camera was a fantasy jotted down on some napkins by an eager visionary, or something that was actively pursued is unknown, but the fact that so little information about it, or any photos have ever been found suggested its development didn’t make it very far.

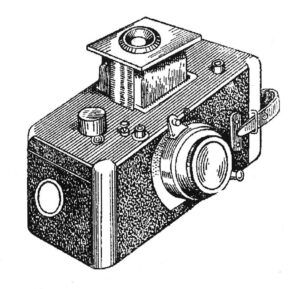

The next step in 35mm SLR development came in October 1934, when the announcement of a new prototype camera called the Гельвета (Gelveta) was mentioned in Sovetskoye Foto #7. The design of the new camera is credited to A.O. Gelgar and reused some of the same concepts as Min’s camera from 1929. Production was already along far enough in 1934 to suggest that work had begun on it the year before. If true, initial development of a Soviet SLR in 1933 coincides with the debut of the Ihagee Vest Pocket Exakta which was announced at the 1933 Spring Fair in Leipzig, Germany.

Similarities between the Gelveta and Min were a vaguely similar rectangular body, magnified viewfinder on the top plate, focal plane shutter with integrated reflex mirror, and use of double perforated 35mm film loaded in special cassettes. Early versions of the Gelveta used a paper backed film and relied on exposure numbers read through a red window on the back door of the camera. The exposed image size increased to 24mm x 36mm which was the more commonly used size by German camera makers and reduced the number of images to fifty per roll.

Two additional announcements for the camera appeared in January 1935 and April 1936. The first announcement gave few details other than that it was an experimental model which reflects images from the lens onto a piece of frosted glass which can be observed through a special magnifying glass. The second announcement gave more detail, saying that production had already begin at the GOMZ factory in Leningrad. The name of the camera was revealed to be the “Sport” instead of “Gelveta” and that it would be like a reflex version of the Leica, using standard 35mm film. Once again A.O. Gelgar is credited as the camera’s designer.

Up to 300 versions of the Gelveta were produced, all in prototype form as the camera was never offered for sale or use by professional or amateur photographers. Various iterations of the Gelveta have been found, with varying cosmetics. The name Gelveta appears on the lens, however not on the body, most of which are engraved with the name Спорт or Sport. No versions of the Gelveta have ever been found with the name anywhere on the camera.

In 1937 an additional announcement would appear in Sovetskoye Foto #11 announcing that the Sport would be delivered by the 20th anniversary of the 1917 Revolution which suggests an October 1937 release date.

The new camera was illustrated as having a few cosmetic changes from the earlier prototype. The most significant is a redesigned body that is more rounded on the edges, most likely making it easier to hold. The top plate of the viewfinder is different with a cosmetic ring around the eyepiece and the removal of two neck strap loops that were on the earlier camera. The front plate around the lens mount is different, and the lens is now identified as an Industar-10. Late versions of the Gelveta prototypes showed a removal of the red window on the back of the camera suggesting that paper backed 35mm film would no longer be needed.

One last change was that in the 1937 announcement, credit for the design of the camera was given to two engineers named Rybnikov and Postnikov without any mention of A.O. Gelgar. In addition to the Sport, four other cameras, the Fotokor, Reporter, Lilliput, and Tourist were also announced for release.

Serial numbers of the GOMZ Sport range from 320 to just over 19000 and were produced until 1941. Along the way, many subtle cosmetic changes were made, along with a few special versions of the camera, some with unpainted viewfinders, green leather, lenses with black rings, and a few other changes have all been found.

In 1941, a few cameras called the Sport-2 were made, which Princelle suggests had some cosmetic changes and an improved shutter which provided more reliable operation, however no images of the camera are included.

One additional camera, a non-reflex stereo camera which exposed 24 x 30mm images on regular 35mm film, was created between 1938 and 1940 by GOMZ. Although this camera was never released and existed only in prototype form, it shared some parts with the GOMZ Sport, namely the Sports unique film cassettes, and the bottom locking mechanism of the camera.

That the Sport was in production for as long as it was and to have over 19,000 made suggests it saw some success. Like most pre-war Soviet cameras, the Sport was never made available for export, so western photographers would have likely never learned of its existence. As to the camera who can claim the title as first 35mm SLR, that the Sport wasn’t officially released for use by photographers until October 1937, over a year after the Kine Exakta, and that very few people outside of the Soviet Union knew it existed, cements the claim for the Exakta. If however, work began on the earliest Gelveta prototype exist from 1933 or even the Min concept in 1929, validates the claim that the Soviets began work on the first 35mm SLR before anyone else.

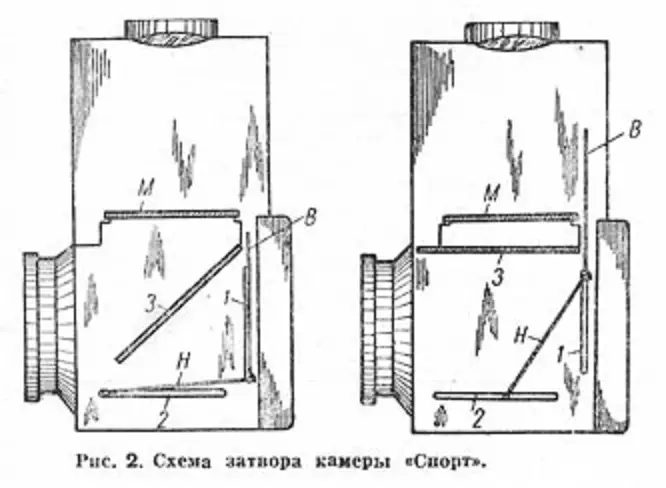

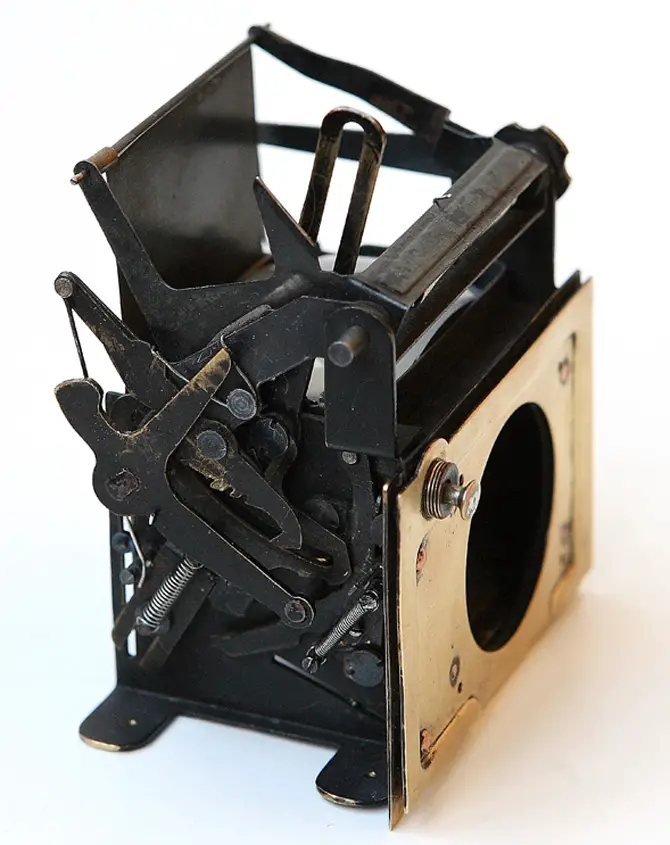

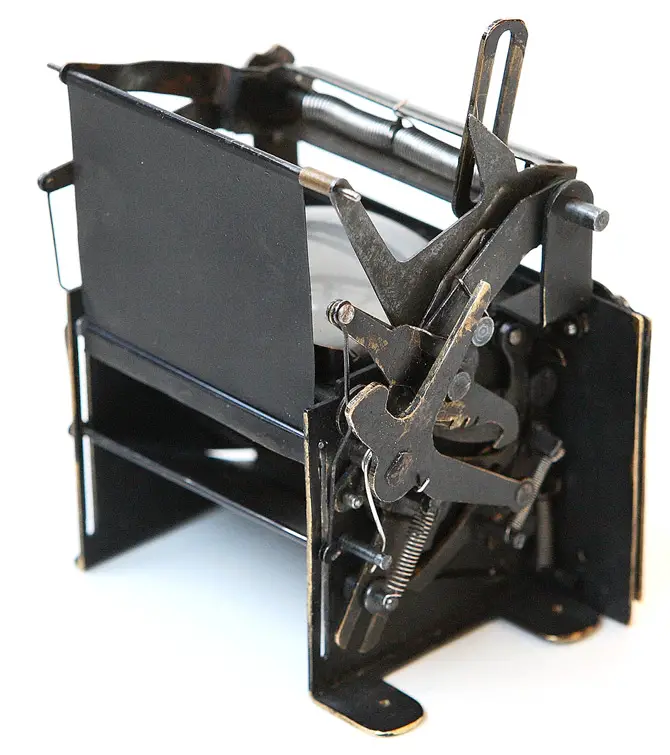

By today’s standards, the Sport is a strange looking camera with features not found on any other SLR, not even the Exakta which is strange by today’s standards. Without a doubt, the camera’s most unique feature was its all metal focal plane shutter. A vertically traveling design which instead of using cloth curtains or folding slats as in the case of the Zeiss-Ikon Contax, the Sport’s shutter consists of two flat metal curtains (indicated by B and H in the illustration above) which move in and out of the focal plane while firing. A shutter speed mechanism on the side of the mirror box delays the movement of the second curtain when the shutter release is fired, offering varying speeds from 1/25 to 1/500 seconds.

When the shutter is set, the mirror (indicated by 3 in the above illustration) drops down at a 45 degree angle, reflecting light up towards a frosted ground glass (M), the first curtain (B) drops down from an area above and behind the ground glass completely covering the film gate, and the second curtain (H) drops down and lays flat at the bottom of the mirror box. While setting the shutter (which also advances the film), both the first and second curtains move together, providing a light tight seal preventing light from leaking onto the film. The reflex mirror (3) is also quite large, allowing additional protection from light leaks.

When the shutter is fired, the reflex mirror (3) flips up out of the way of the path of light, the first curtain (B) moves straight upward into its original position, and a delay mechanism prevents the second curtain (H) from raising back to its original position allowing for whatever shutter speed is chosen.

The two images above are courtesy of photohistory.ru and are credited to Alexey Nikitin, and show the shutter mechanism removed from the body. In both images, the shutter is not set, with the first curtain in the raised position. You cannot see it, but in this state, the reflex mirror would be in a raised position, blocking light from entering the viewfinder. In the second image showing the back side of the shutter, there is a gap between the first and second curtains which normally wouldn’t be there. It is unclear whether this is done intentionally to show separation between the two curtains, or if these images are of a defective shutter.

To illustrate how the Sport’s shutter works, I made two videos showing the action of the shutter being set and fired at various speeds. In this first video, I show how the two curtains move and what it looks like while firing at 1/25, 1/500, and Bulb.

In this second video, I show the shutter firing in slow motion. You can very easily see the separation between the two curtains at the moment of exposure.

While researching this article and playing with my own camera, I can’t help but marvel at the simplicity and effectiveness of the Sport’s shutter design. For starters, it is a vertical design, which is something Dr. Heinz Küppenbender saw the value of when designing the shutter for the Contax rangefinder. Vertical shutters are the dominant style used today and have a shorter distance to travel (24mm vs 36mm) than horizontal shutters, allowing for more precise speed control and faster flash synchronization. The all metal curtains are immune to pinholes and tears, and are generally stronger, meaning that they should be more resistant to damage than cloth curtains or the delicate silk straps of the Contax shutter’s design. Finally, the overall simplicity suggests a shutter that would be less costly to build and easier to repair in the event of failure.

The biggest con to the design of course is how large it is. The large rectangular box on top of the main body is not only used for the viewfinder, but also for the first curtain when the shutter is not set, resulting in an overall awkward design of the camera. Still, considering how many other companies were developing early versions of SLRs in the 1930s and even into the 1940s, I am surprised that at least a few other companies never developed a shutter similar to the Sport’s.

This is the part of my review where I usually talk about marketing and what a camera might have cost when new, but Soviet cameras were not typically advertised in nationwide photo magazines. Articles appeared in a few publications, but not with full page ads like you would find in Western countries. I could not find any period ads or reviews for the GOMZ Sport, but in the 1936 article from Sovetskoye Foto written by D. Bunimovich, the price of the GOMZ Sport was estimated to be around 800 – 850 rubles with a future price drop to 550 – 600 rubles. It is nearly impossible to correlate modern US dollars to pre war Soviet rubles as the economies of both countries were very different, plus the difference of 80 years adds additional complexity. However, knowing that precision cameras were almost always out of the reach of an average Soviet factory worker, it can be assumed that at whatever price the GOMZ Sport sold at, it was probably unaffordable by all but the wealthy, or well connected.

Most references suggest that the GOMZ Sport ended production around 1941, which makes sense as that was near the beginning of the Soviet Union’s role in World War II. Like every other country at that time, the focus shifted away from producing things like cameras, and more towards war production. It is possible that had the war never happened, we would have seen further development of the Sport line. That the Ihagee Exakta was become established as the preferred 35mm reflex camera would have at least suggested that any future Soviet SLRs might have had significant changes, but it stands to reason that development would have continued.

Instead, in the years following the war, the most common Soviet cameras were copies of the Leica II made both by FED and KMZ. Development of a new Soviet 35mm SLR would commence in 1951 with the KMZ Zenit, a camera that answers the question, “what if you took a Leica rangefinder and put a mirror box in it?” The Zenit would be further developed over the course of the rest of the 20th century and become one of the highest produced 35mm SLRs ever made, and while the Zenit shares almost nothing in common with the GOMZ Sport, it owes at least a little bit of its lineage to its prewar ancestor.

Today, the GOMZ Sport is well known by collectors of all kinds. That it is an interesting looking, rare, and historically significant camera adds to its appeal, whether or not you are interested in Soviet cameras. With a total production of just over 1900 means that there are enough of them out there to where if you want to find one you can. The prices may be high, but if you want one bad enough, you can find them. As I write this, a quick eBay search returns 7 cameras for sale internationally, ranging in price from $799 to $2269. Whether or not that’s something you are willing to spend your money on, is up to you, so if you are not, hopefully you are enjoying this review!

My Thoughts

I remember when writing my first review of the Ihagee Exakta, I followed the general claim that the original Kine Exakta was the world’s first 35mm SLR, Of course, Soviet collector fans are often quick to point out that the GOMZ Sport, and the Gelveta prototype predated the Exakta’s release, that these cameras were not available or in widespread production until 1937, one year after the Exakta was on sale, cemented my stance that the German camera could claim the title as “first ever”. Besides, it’s not like I’ll ever get a chance to shoot a GOMZ Sport, would I?

Apparently, I would! In the summer of 2023, as I was in charge of dispersing of the camera collection of Kurt Ingham, I came across this GOMZ Sport in an upstairs closet and upon opening the leather case it had been resting in, I was amazed at what I saw! Such a beautiful, rare, and historically significant, resting next to a box of unused GE flashbulbs! I could not wait to get this thing home and learn more about it!

The GOMZ Sport is as strange looking in person as it is in pictures. Resembling a fat Leica with a huge rectangular box grafted on top, this is unlike any other SLR you’ve ever seen. The build quality of the camera is somewhere between haphazardly put together prototype and run of the mill Soviet rangefinder. Machining marks are evident under the black enamel which in places looks like it was painted on with a brush, there are variations in the finish of the nickel metal parts around the lens opening and the shinier pieces elsewhere on the camera. The top half of the camera is covered in an attractive black crinkle paint, whereas the bottom is glossy and covered with a soft leather. None of this is to say that the Sport isn’t well put together, but its early, handmade design is very evident in the finish and quality of materials used in its construction. This is the only GOMZ Sport I have ever held, but I would suspect that no two cameras are exactly the same as the hand finished nature shows minute sample variations.

Despite its odd shape and bulbous dimensions, the GOMZ Sport is surprisingly easy to handle. The thickness of the body front the back, combined with the short shoulders to the left and right of the rectangular viewfinder make gripping the camera easy. With my right forefinger resting on the front shutter release, I felt assured in my grip of the camera, and suspect I would be able to main good comfort while shooting the camera for an extended period of time. Weighing in at a reasonable 736 with the Industar 10 lens mounted, but no film, the camera weighs 736 grams which is 152 grams lighter than a prewar Ihagee Exakta with waist level finder and Schneider-Kreuznach 50mm f/2 Xenon lens.

From pretty much every angle, the GOMZ Sport looks unlike any SLR ever made, and that starts with the top. Featuring a large round eyepiece for the top down eye level finder. Despite facing up, this is not a waist level finder as you cannot see much of the image when holding the camera at your waist. You must lift the camera all the way, very close to your eye to see the entire image through the eyepiece. Apart from a metal finger which helps indicate shutter speeds, there is nothing else to see on the raised top portion of the camera.

On the right side of the viewfinder box is the combined shutter speed selector, film advance, shutter setting device, and manual resetting exposure counter. The main part of the round selector has a knurled pattern which makes it very easy to turn. Under normal operation, this knob only turns forward, to advance the film and set the shutter. Once a full rotation has been made, the knob locks into position and will not move again until after the shutter is fired.

A shiny nickel plated collar goes around the selector, closest to the viewfinder, and is marked with shutter speeds 25 to 500 plus Bulb. To change shutter speeds, you must press the entire knob inward towards the viewfinder while rotating it. While changing speeds, you may twist the collar in either direction, even if the shutter is cocked. A metal finger, which I previously mentioned is sticking out from the top of the viewfinder is your shutter speed indicator. While maintaining inward pressure on the collar while rotating it, line up your chosen speed with the metal finger and let go of the collar and it should snap into position. If it does not, a gentle jiggle of the collar should allow it to properly seat. While testing this camera, I found it easier to change shutter speeds after the shutter is set, although you can do it with it not set, just the numbers won’t line up correctly until after setting the shutter. With the shutter fully set and your chosen speed lined up with the metal finger, you are ready to make an exposure.

The exposure counter is manually reset by turning it using two little posts which are located 180 degrees opposite each other. Numbers are engraved from 0 to 49 which is because the film cassettes designed for the GOMZ Sport allowed for up to 50 exposures per roll. The exposure counter is additive, showing the number of exposures made.

Flip the camera over and the film door release key is prominently located in the middle, with a 3/8″ tripod socket in the center. The location of the tripod socket and film door release not only gives the base of the camera good symmetry, but also means it would be balanced when mounted to a tripod. The use of a larger 3/8″ tripod socket was common with Soviet cameras until the late 1950s. The film door release key is not indicated which direction is locked or unlocked, but a good rule of thumb is the key will only fold flat in the locked position. With the key unlocked, you cannot fold it flush with the bottom of the camera.

Around back, apart from the leather covering of the body and back of the viewfinder, the only thing to see is a straight through optical viewfinder in the upper left corner of the viewfinder box. That the GOMZ Sport is an SLR with both a reflex finder and optical viewfinder was not unusual, as early SLR cameras made by Alpa, KW, and Asahi Optical had both kinds as well. Beyond the optical viewfinder, there is nothing else to see.

The sides of the body have absolutely nothing to see, not even strap lugs which are not present on any version of the GOMZ Sport. If you had a need to carry this camera along with you, you better have the original leather ever ready case with a good strap attached to it. From the side you can get a good idea of how thick and strangely shaped the body is.

Looking down upon the top of the Industar-10 lens, it is difficult to see the focus scale, which is engraved into the back of the lens which is angled downward towards the body. Distances from 1 meter to infinity are engraved, but frankly, are too difficult to see under normal shooting conditions. Anyone using this camera would have almost certainly used the reflex finder to confirm focus accuracy.

Up front, the name of the camera, “Спорт” is engraved into the front face of the viewfinder box, with a round gold and black GOMZ logo above and to its left. The viewfinder opening is above and to the right of the logo. On the main body of the camera, near the 10 o’clock position of the lens is the cable threaded shutter release button. This location is very comfortably located and within easy reach of your right index finger while holding the camera.

The GOMZ Sport has an interchangeable lens mount, however according to research, no lenses other than the original Industar-10 were ever made for it so there really is no reason to ever change the lens. If you would like to remove it however, a small finger sticking through the side of the knurled focus ring unlocks the bayonet, allowing a quick counterclockwise twist to remove the lens. Installation is the opposite of removal. The focus ring has two posts sticking out from the side, near the aperture scale. The post nearest the top of the camera is an unlock for the bottom post. When the lens is set at infinity, the focus ring locks into position, similar to a Leica. To unlock it, squeeze the two posts together while pressing down on both and it will unlock, allowing you to choose something other than infinity. Finally, the front face of the Industar-10 lens has the aperture ring with engravings from f/3.5 to f/16.

Serial Numbers: Most GOMZ Sports do not have a serial number anywhere on the body. The only number is engraved on the front of the lens, but since they are interchangeable, it can be difficult to know which camera is which.

The back and bottom come off the camera all in one piece, similar to the Zeiss-Ikon Contax from 1932. Whether or not the designers of this camera were inspired by Zeiss-Ikon and not Leica is anyone’s guess, but with the back removed, you get a good look at the film compartment. Everything looks fairly ordinary for a 35mm camera, film transports from left to right over the film gate and across a metal shaft with two rolls of sprockets for the exposure counter. The GOMZ Sport uses a cassette to cassette loading system, and while it uses regular double perforated 35mm film, the cassettes are unique to this camera.

The cassettes are larger than ordinary 35mm cassettes, allowing for up to 50 exposures to be made on a single roll. Rewinding the film is not possible, nor is cutting it mid roll like in an Exakta, or later KMZ Start SLR. The cassettes themselves are a five piece design, consisting of an inner spool, the main body of the cassette, two caps that hold it together, and a spring which slides into a channel, keeping it from rotating while in the camera. Other than its larger than usual size, the GOMZ Sport’s cassettes are like most reloadable metal 35mm cassettes of the day. If you have a GOMZ Sport and ever wish to shoot the camera, you must have both cassettes, as the height of the original cassettes and spools is shorter than usual 35mm cassettes, so repurposing one from another camera is not possible.

The film compartment’s construction is a bit crude, with machining marks visible in the metal, and sharp edges all over the place. The inside of the take up side has exposed gears whcih are part of the film transport system. The thin metal pressure plate on the inside of the door looks hand formed and loosely wobbles around with it removed from the camera. Black yarn light seals line the top channel of the film compartment, beneath the top plate of the camera, protecting the film from light leaks.

Film transports from left to right. With film loaded in a supply cassette on the left, you must attach the leader to the inner spool of the take up cassette with the film compartment open. You will waste the first few inches of film doing this, but at least you’ll know the film is securely attached before closing the film compartment. Once everything is ready to go, reset the exposure counter to zero, close the back and fire off a blank shot or two to get past the exposed portion of the film.

The GOMZ Sport has two viewfinders, a straight through optical on in the upper left corner of the back of the camera, and an eye level reflex viewfinder up top. The optical viewfinder is ideal for fast action shots where your subject is at or near infinity. For these type of action shots, seeing focus and getting exact framing is not necessary. Unlike other SLRs with top facing viewfinders, the one here is not a “waist level” finder as you cannot see through it with the camera lowered from your face. To see the entire ground glass, you must hold the camera very close to your eye just like as if it has a pentaprism. When I say “very close to your eye”, I mean it as it is impossible to see everything while wearing prescription glasses. You need to physically push your eye almost inside of the black ring to see everything.

Once you do however, the viewfinder is surprisingly bright for a 1930s SLR. In the gallery above, the reflex viewfinder image is darker than it appears in real life as my cell phone wasn’t able to see through the round eyepiece to capture the corners, giving it much more vignetting than is really there. The GOMZ Sport predates both instant return mirrors and automatic diaphragms by almost two decades, so you’ll need to set the shutter before you can see anything, and the brightness changes depending on which f/stop you’ve selected on the lens. If you want the brightest possible image, you’ll need to open it up to f/3.5, but remember to stop it down again before firing the shutter.

Like all other “top down” reflex cameras, the viewfinder image is horizontally flipped, so that moving the camera to the left shifts the image to the right, and vice versa. A single horizontal and vertical line is etched into the focusing screen through the central axises, which can be used to level out the camera to the horizon, or some kind of vertical object. Vignetting is visible near the corners which makes seeing the corners a challenge in dim light, but is hardly an issue outside in good lighting. Overall, the reflex viewfinder is better than some SLR viewfinders from the 1940s and even early 1950s, suggesting the Soviet creators who designed this camera knew what they were doing.

The GOMZ Sport is a strange looking camera that clearly shows its roots from an era when established norms for what a 35mm SLR should look and work like, weren’t yet decided. Despite its many oddities however, the camera is easy to use. Cock the shutter and advance the film by turning a knob, look through a reflex viewfinder, focus your image, check your exposure, and press the shutter release. Once you get the camera loaded up and familiar with its controls, this uncommon 1930s Soviet camera is just as capable of nice images as any camera made decades later. But what is it like to use? Keep reading…

My Results

When the GOMZ Sport came to me, it appeared to be in working condition, but I had no clue of how accurate the shutter was, whether the film compartment was light tight, or did I have any faith in my ability to load the special cassettes that the camera uses, so I played it safe and loaded in a short strip of bulk Kodak TMax 100. In addition to being a great all around film, I find that films around ASA 100 work best with shutters of questionable accuracy as 1/100 to 1/125 shutter speeds tend to be the most reliable.

The above seven images were the best from about 20 I took. Although the shutter appeared to be in working order, the GOMZ Sport suffered from massive film transport issues. In my preliminary tests, everything seemed to work fine with the camera open, but once film was in the camera and the back closed up, the additional stress of film actually transporting through the camera resulted in massively overlapping frames. I could feel the sprockets shredding the film perforations as I turned the advance knob. Suspecting this was happening, I made it a point to shoot a photo, then fire off a blank frame, and then a photo, alternating between blank frames thinking the film would advance enough in the blank exposure to not overlap as much.

Once I was able to develop the film and see my suspicions were correct that each turn of the knob only advance the film about half of what it needed, but that otherwise the images looked good, I decided to give the camera another go, this time using my “alternating blank exposure” method. Encouraged by the test roll using Kodak TMax, I thought it would be fun to shoot the Soviet camera with something more “Soviet”. I didn’t have any viable period correct film, so I went with a fresh roll of Svema FN64 which I recently purchased from the Film Photography Project. Svema FN64 is a current film made in Ukraine whose roots date back to the Cold War, so I thought it would be a good match.

There are cameras you expect to be great and they are, there are cameras that you hope to be great but they aren’t, there are cameras you expect to be bad and they are, but then there are cameras which you have no idea what to expect. The GOMZ Sport is the latter.

Before loading film into the camera, I spent a lot of time familiarizing myself with the controls. Turning the shutter cocking and film advance knob was relatively easy to do and the shutter seemed to fire correctly at all speeds, but I noticed that after putting in some film, there was quite a bit more resistance turning that knob than before. I was concerned about film transport problems, or that while using the camera, it would just lock up and stop working so I operated the Sport as if it was a fragile time bomb, ready to go off at any moment. Thankfully, I made it through two rolls of film with only one issue which I’ll get to later.

Looking at the images from both rolls of film, I was impressed both with the sharpness and accuracy of exposure. It seemed as though the nearly 90 year old Soviet shutter was still working correctly at all the speeds I used it at. The vertically traveling metal shutter showed no signs of capping, light leaks, or blank exposures. I did miss focus a few times and in my excitement, I underexposed a few interior shots, but overall, the images came out way better than I had ever hoped for!

The images from the uncoated 4-element Industar-10 lens were superb and easily as good as many other more highly regarded uncoated German lenses. I should point out that in the image to the left of the lens, there is a strong blue cast in the glass which resembles a lens coating, but is actually a result of the blue sky reflecting back into the glass. I got a little heavy handed with the Saturation slider when editing these photos, but trust me, this is definitely an uncoated lens.

Images showed excellent sharpness in the center with only subtle softness and vignetting creeping into the corners. That this is an uncoated lens, I stuck with only black and white film but predict that had I used color, I would have seen the typical muted colors and subtle flaring characteristic of other uncoated lenses by Zeiss, Schneider and other companies.

In addition to the accuracy of the shutter and the quality of the images, another thing that impressed me about the camera was how easy it was to use. This camera was designed at a time in which nobody knew what a 35mm SLR should look like or how it should operate. Although Ihagee would release the Kine Exakta a year before GOMZ put the Sport on sale, it is unlikely anyone in Leningrad had seen an Exakta when building this camera. Considering this was essentially an experimental model with features and a design that probably favored function over form, it impressed me how little the camera got in the way while shooting.

The combined film advance and shutter cocking dial that doubles as the shutter speed selector and exposure counter is really well designed. In an era where essential camera controls are often haphazardly strewn about the top, bottom, and side plates of cameras, to have four controls all in one, easy to use location was a really smart move, and something I wished other cameras had.

Another small, but nice touch to the lens is the design of the infinity lock on the Industar lens. The focus arm is made up of two metal posts. Under normal operation, focusing the lens requires you to rotate the lens with either of these posts, but when the lens reaches infinity, a latch locks the lens at infinity, similar to how the same feature works on most Leica Thread Mount cameras. Instead of pressing a button to release the lock, on the Sport, you simply squeeze the two posts together to release the lock. I find this to be a simpler and much more smooth process than what you see on your typical FED or Zorki rangefinders.

Using the viewfinder was the most difficult part of shooting the Sport as you really do need to press your eye uncomfortably close to the round eyepiece, and even then, it is difficult to see all four edges of the focus screen. For prescription glasses wearers like myself, the problem is even worse as while shooting, I could maybe see only the center third of the entire image, requiring me to extrapolate the rest of what I was about to capture. Despite this one issue, I still applaud the design of the viewfinder as it was unexpectedly bright considering the era in which this camera was made.

Beyond the viewfinder, I only had minor nitpicks with the rest of the camera. I did not like the design of the shallow lens and how it put the focus scale so close to the body making it hard to read. I also didn’t love having to change apertures by using a ring on the face of the lens, but to GOMZ’s credit, thats how many Leitz and Zeiss lenses of the same era worked too. Finally, loading film into the camera was a bit of a challenge, but that can easily be excused as almost everyone had a different opinion for how a 35mm cassette should work then.

For what minor complaints I have above, none significantly impacted my enjoyment of using the camera or the results I got. Add to the fact that this is an experimental Soviet 35mm SLR from the 1930s, and you end up with an immensely cool and fun camera to shoot. I know that finding these cameras today is very difficult (and expensive), and I am sure that very few can be found in good working order, but my experience with the GOMZ Sport reinforces why I love this hobby so much. Anyone can shoot a Nikon or Minolta SLR, but when you find a camera that has a very interesting history and unique design, and still manages to be fun to use and makes great results, its difficult to find the words to accurately reflect how much I like this camera.

I fully understand that there are very few people who will read this who will ever have a chance to shoot a working GOMZ Sport, but if you do, take it! This is one cool camera!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Sport_(SLR)

https://sovietcameras.org/sport/

https://sovietcams.com/cameras/detail/43cz1qmwnn4yx5d20r1dwhs551

http://www.photohistory.ru/1207248178962562.html (in Russian)

http://www.photogallery.it/storia/icnopm.html (in Italian)

So typical of the USSR, design and produce an interchangeable lens camera, never make any other lenses for it…

You’re not wrong, but to be fair, there are plenty of other camera makers from other countries that produced a dead end lens mount as well. The Japanese Tanack V3 was made with a bayonet and no lenses ever we made for it. When the camera went on sale, the company sold it with a Leica Thread Mount lens with a bayonet adapter mounted to the camera since there were no lenses.

Mike, it is a common myth that no images of the A.A. Min’s “Filmanka” prototype camera exist. I can e-mail you a image of an article in Soviet Photography, which shows a real working camera and also explains it’s possible use as an enlarger and projector. In these photographs the viewfinder is of a folding down to the body type, like on a Rolleiflex.

The prototype was submitted to an evaluation committee, which gave a very positive assessment and recommended that the work should proceed on manufacturing it, but for some reason this was not done.

I also have an image of the Galvetta with the name on the upper body of the camera. It looks like a newsprint photograph, rather than an engraving.

On a related topic, Gelgar, the original designer of the Galvetta, went on to design the rotating sector shutter of the Kiev 10 and Kiev 15 SLRs manufactured by Arsenal.

My mistake, the article and photos are from Proletarskoe Photo, Issue 3, 1933. The article bemoans the fact that A.A. Min’s novel design and prototype have still not been taken up for production despite the positive assessment given by the committee of experts. Pages on Mike’s Facebook page.