In the history of photography, there have been a LOT of different film formats. In a Wikipedia article about the history of film formats, a chart showing 71 different formats of film is listed, including a large number of roll film, film pack, sheet, and cassette formats.

A majority of these film formats are from the early 20th century when the state of the photographic industry was like the wild west, with little consistency between manufacturers. Some formats of film might have only been used with one or two different kinds of cameras. Of the ones that were more popular, formats like 127, 620, and 828 formats have all disappeared, last being made by Kodak in 1995, 1995, and 1985 respectively.

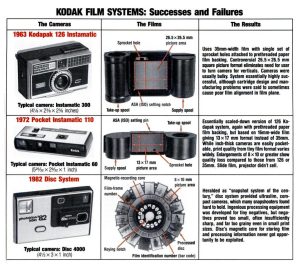

Without a doubt, Kodak’s most successful film formats were 120 roll film and their Type 135 Daylight Loading 35mm film, both of which are still made today. Since the rise of these two formats, Kodak has littered the grave yard of extinct film formats with Type 126 Instamatic, Type 110 Pocket Instamatic, Kodak’s answer to Polaroid Instant Film, and in the 1980s, Kodak Disc Film.

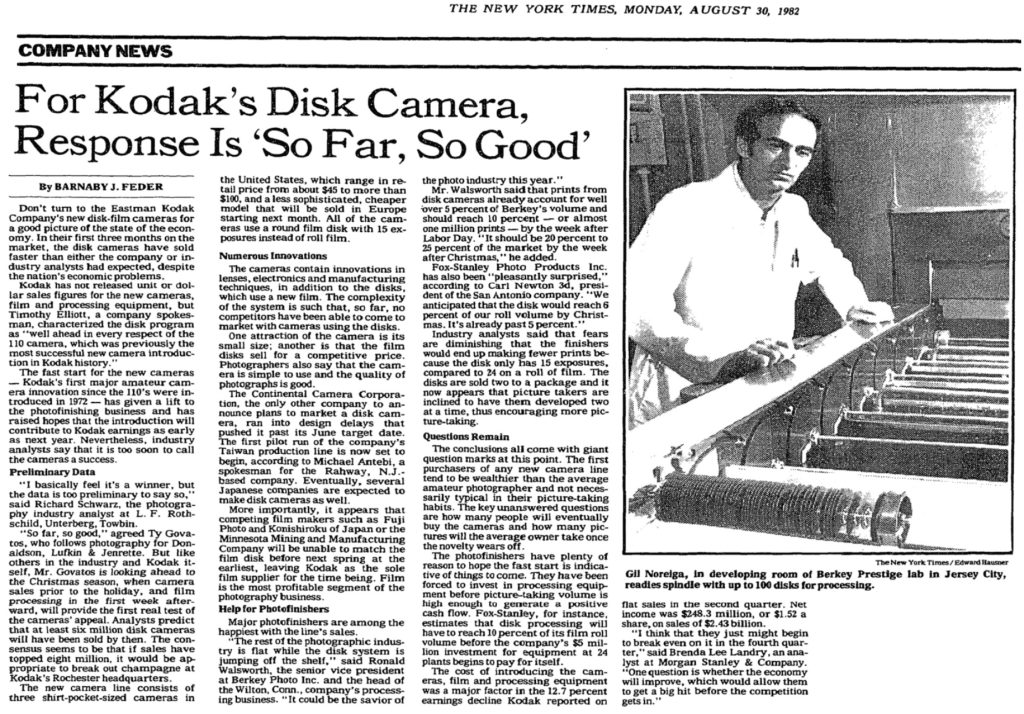

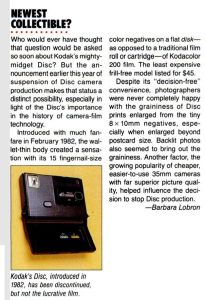

There aren’t too many people who remember Kodak’s Disc format with fond memories. The images were incredibly tiny and of poor quality, the cameras were very basic, and well the format just didn’t make sense. Of course, hindsight is 20/20, but on February 3rd, 1982, the day Eastman Kodak launched Disc film, there was a lot to be optimistic about.

This, the 103rd Keppler’s Vault brings to you a variety of articles, all from 1982 issues of Popular Photography. The first is a short one page preview written by long time writer Arthur Goldsmith suggests that years of development rumors preceded the release of the new format. Goldsmith praised the unique look of the new cameras, saying that it had an impressive amount of technology, including a sophisticated 4-element lens, lithium batteries with 5 year shelf life, and automatic everything. Coinciding with the release of the new format was a new type of 200 speed Kodak color film which was capable of higher resolutions than ever before, certainly something that was useful for a camera making 8mm x 10mm images. Near the end, Goldsmith suggests that the excitement of Kodak’s new format matched that of other releases like the Nikon FM2 and Canon’s new focus assist AL-1.

The second article is the most technical, covering a bit of the history of the new format’s 5 year development. Author Don Leavitt breaks the two and a half page review into sections covering the development of the system itself, the film, battery, advances in photofinishing and finally, the cameras themselves.

While I found this whole section fascinating, the most interesting to me was the discussion of the film as it seems Kodak’s goals for the system predated the disc format itself. Always looking to improve upon earlier formats, Kodak was aware of the challenges making a sharp images using both Type 126 Instamatic and Type 110 Pocket Instamatic films. Each of those formats use standard film in a plastic cassette which lacks a pressure plate. Getting the film to lay perfectly flat in the film plane was a challenge to both formats, and one of many reasons that neither really caught on in the midlevel and professional markets. It didn’t matter how good of a lens or a camera you would design, if the film didn’t sit flat, it wouldn’t be sharp.

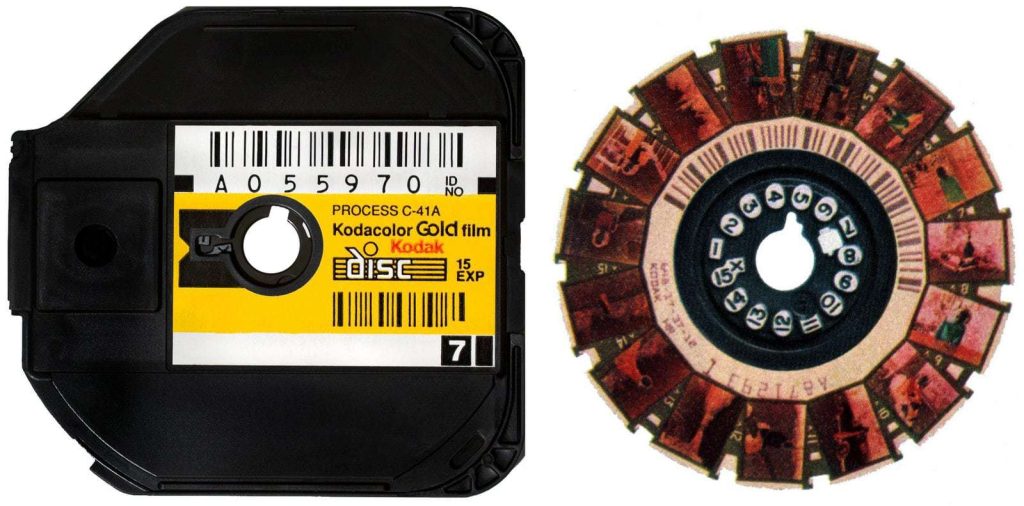

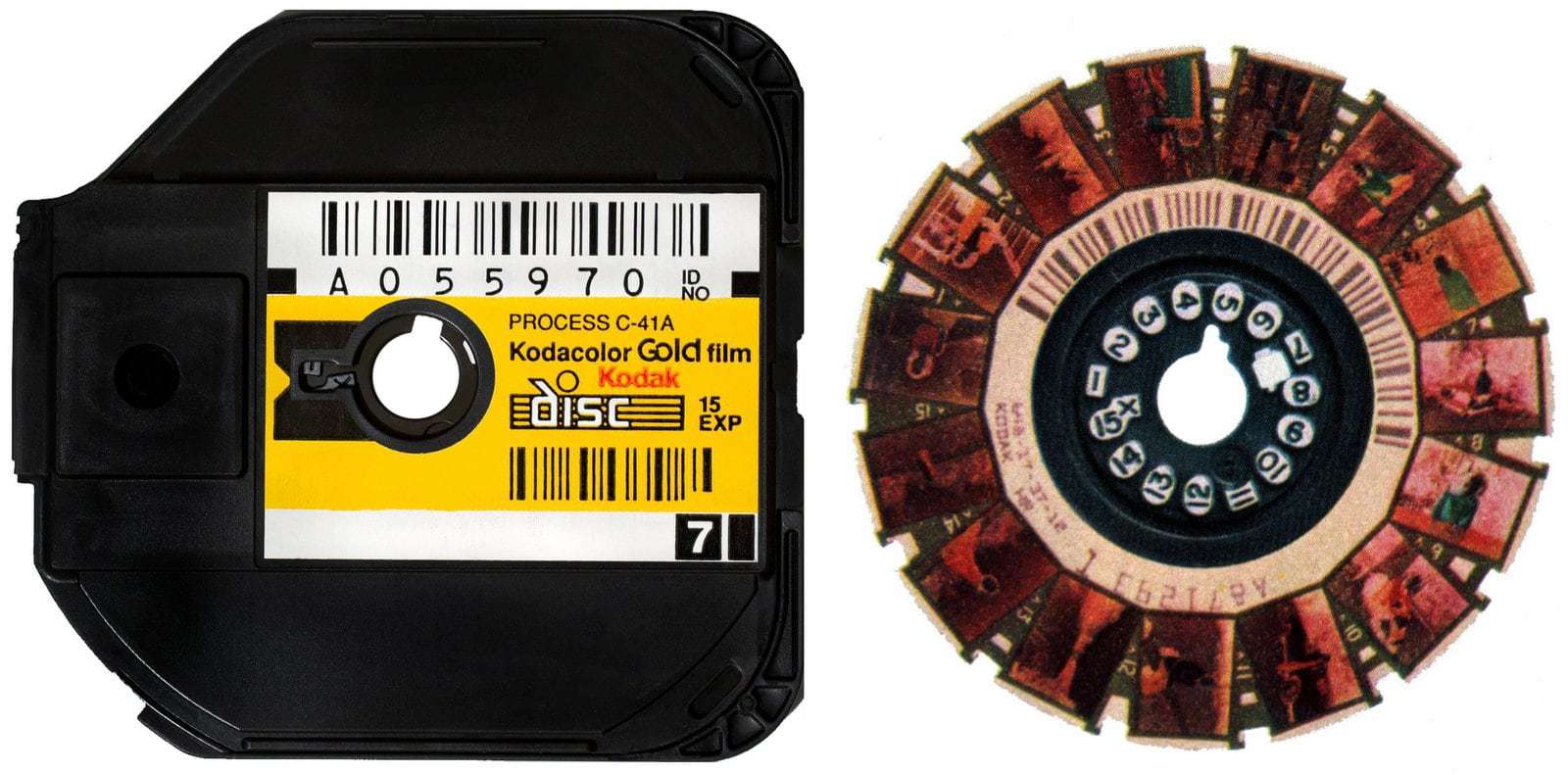

For the new system, Kodak decided on a much more rigid 7 mil thick Estar base which they used for 4×5 and 8×10 sheet film. The film could lay perfectly flat, but didn’t like being rolled up, so in order to maximize the flatness of the thicker film, the idea of a disc format came to fruition. Each round cassette would contain 15 exposures surrounding a center hub on a piece of Estar film that would always lay perfectly flat in the film plane, without the need for a pressure plate. This section concludes the film was designed first, and the camera around it.

As it turns out, the flat design of the camera, made choosing a wide angle and very shallow lens easier to construct as with a short focal length, depth of field was improved, allowing for nearly focus free operation, and a very short distance from front lens element to film plane. As an added bonus, the lenses could be made with a large aperture of f/2.8 which was quite a bit faster than Kodak’s inexpensive 110 cameras.

In addition to a fast and sharp lenses, the new Kodacolor HR film was an all new emulsion, reformulated with smaller grain which maximized sharpness, allowing for good quality 4×5 and 5×7 prints to be made without noticeable loss in quality. Even after the release of the format, Kodak would continue investing in ways to shrink the size of grain, eventually creating T-grain emulsions in 1985, which would eventually find their way into other films such as Kodak Tmax and Portra.

The lithium battery used in Kodak’s disc film cameras was all new and made by Matushita (Panasonic). Kodak guaranteed the battery for up to 5 years which they suggested was good for 133 full discs of film. If the battery ever were to die, it could be sent to Kodak for replacement. Leavit suggests the most exciting possibility with Matsushita’s new battery might be in other applications of the technology in other camera formats (he was right).

An often overlooked element of a new film format is photofinishing. After all, what good is a new film format if you can’t ever develop or print the images? Quite a bit of thought was put into the new format, including computer readable exposure numbers and a unique serial number on the center spool of each disc, simplifying ordering prints and helping to reduce the chances of the film being lost during development. In addition, a magnetic ring was also included which Kodak envisioned could be used by later, more advanced cameras to encode printing and developing instructions. Such a system was also planned and implemented in Kodak’s later Advanced Photo System film format from 1996.

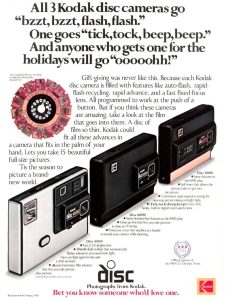

The final section covers Kodak’s three launch cameras, the Kodak Disc 4000, 6000, and 8000 models. All three models used the same 12.5mm f/2.8 four element lens and auto exposure systems, but added features like metal cases, close focus, and (strangely) an alarm clock in the 8000 model. Each of the three cameras had a retail price of $67.95, $89.95, and $142.95. A 15-exposure pack of the film itself would carry a retail price of $3.19 with a two pack option for $5.90. When adjusted for inflation, each of these prices compare to $210, $280, $440, just under $10, and just over $18 today.

The final two articles discuss the possibility of developing Kodak Disc film at home, and Disc Film Cameras made by third party companies like Haking, Hanimex, Continental, and a few others.

As I dug further through back issues of photography magazines, I found a few other interesting articles such as the two below, from May 1982 which have a few testimonials from “experts” on the format, and a short preview of Continental’s Disc cameras.

Praise from the first four experts was very positive, using the word “brilliant” multiple times. The fifth, Henry Wilhelm was less impressed but at least predicted it would be a moderate success.

Fred Spira from Spiratone predicted that the Disc format would sell so well, that it could actually boost the sale of more advanced formats as more and more people are turned onto photography and might one day be looking for an upgrade path.

Paul Klingenstein from both Kling and Berkey Photo predicted the film would have sensational sales, and that as a Kodak shareholder himself, he was delighted.

Overall, the experts all seemed to think that there would be a market for the new cameras and film format and that Kodak had done a good job at properly releasing a quality product rather than rushing something to the market before it was ready. So what went wrong?

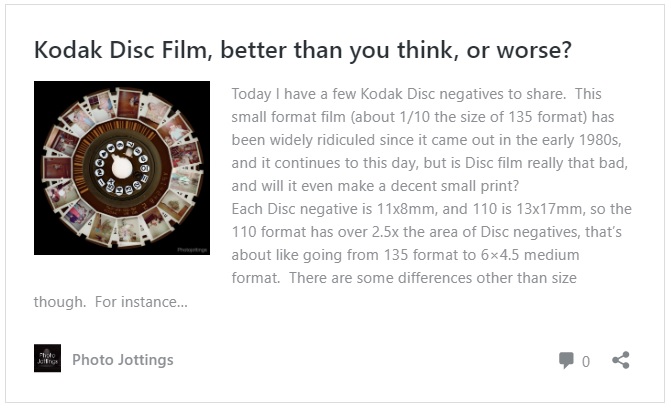

Despite a huge amount of early fanfare and consumer excitement, sales of the new format slowed pretty quickly. The most obvious answer was that despite Kodak’s improvements in shrinking grain size in the Kodacolor HR film, and the use of a sharp 4-element lens in the cameras, image quality was still pretty low, especially in images taken in low light. Furthermore, enlargements larger than a postcard further revealed the limitations of the 8mm x 10mm image.

At least part of the problem with image quality wasn’t the fault of the cameras or the film however, as photofinishers resisted Kodak’s requirement to upgrade their lab equipment to include newer 6-element lenses, instead relying on older 3 and 4 element lenses, which further reduced the image quality of enlargements.

The unique shape and small size of the camera initially had “wow factor” but like so often happens with new products that look different from established norms, the excitement over the small and flat cameras faded quickly.

Finally, and what perhaps was the biggest failure of Kodak Disc film was the same exact thing that caused both the Instamatic and Pocket Instamatic film formats to fail, which was the success of regular 35mm film. During the era right before the release of Kodak’s disc film, features like full programmed auto exposure and auto focus were reserved for more expensive models. In 1982, there wasn’t a single 35mm SLR with in body auto focus and point and shoot cameras like the Canon AF35M and Nikon L35AF had prices approaching $200 which was quite a bit higher than the entry point into Disc film. These cameras usually lacked quick film loading and in some cases still required the photographer to manually rewind film at the end of each roll.

Within a few short years, advancements in the 35mm segment produced point and shoot cameras that were easier to use, and less expensive than ever before. By 1985, if you were in the market for a simple and inexpensive camera, entry level 35mm point and shoots offered all the same advantages of Disc film, but with significantly improved image quality and the economy of 24 and 36 exposures per roll, for not a whole lot more.

Kodak would discontinue making Disc cameras in early 1988, with their competitors soon to follow. Although the film was still produced until December 31, 1999, the format’s days were numbered.

It is easy today to look back at Kodak Disc film and declare it a failure, but that would be too easy. This begs the question, how bad was it really? In the months I prepared for this article, I went back and forth on whether I wanted to go out and buy a Disc camera or two, see if I could get it working, and if so, shoot some film, find someone to develop it, and then scan it in.

Thankfully, at least two other Internet bloggers did that for me, so rather than show you my own results, here are two wonderfully written articles that each show some sample images shot on Disc film.

https://cameralegend.com/2019/01/23/the-worst-cameras-of-all-time-2-the-kodak-disc-camera/

Disc film cameras still show up in our local thrift shops. I leave them there, for the reasons you’ve presented. OTOH, the many 35mm p&s models that appear – even the “Bentley” and “Sports Illustrated” models – can be taken home for $2.

Big companies can’t resist making big mistakes. Kodak throughout the 60’s and 70’s showed total distain for picture quality over profit margins. Photo stores pushed low prices for cameras and overcharged on processing. Meanwhile the public ignorance over photography climbed to new heights. No one wanted their picture taken unless they were dressed in their Sunday best.

I don’t disagree with what you said, but I don’t necessarily think Kodak didn’t care about image quality, I just think they underestimated the target market. They were so hell bent on making easier to load and unload cameras with Instamatic 126, Pocket Instamatic 110, and Disc film, that they didn’t realize the majority of people were happy with 35mm. The one good thing that did come from Disc cameras though is that T-Grain films like Portra and TMax greatly benefitted larger formats, but were first produced in the Disc film era.

Fascinating reading the background to the Disc format. A couple of years go, I added a Disc 4000 to my collection as representative of the format. Boxed, two films and all literature for very little money. I see that Kodak produced the 4000 from 1982 to 1984, and they indicated that the battery was good for at least 5 years. I’ve just checked mine again and it still powers up, 38 years later! How’s this for longevity?

One thing I did see on the ‘net at the time was a reference that the lens reputedly resolved over 2000 lpm. Unfortunately, a search just now doesn’t throw this source up. Any thoughts on this, Mike?

Just imagine the result if Kodak had simply incorporated all this new technology and film in a new, improved pocket 110 camera. Terry

I was thinking more along the lines of applying the emulsion for APS cameras. I have a lovely mint Canon IX which I play with with a couple of Canon lenses. Now, many years after it was popular, I am surprised just how good the spec and features of this camera are. I didn’t get one originally as I did my own d&p but how I would have loved to use one back then were it not for this.

Someone in my family—I think my sister—had a Disc 4000 in the early 80s. As I recall, the ergonomics were quite good; I liked shooting it much better than the cheap 110 camera that I had at the time, and IIRC the prints were better than those from my 110 camera as well.

Also remember that the compact disc digital audio format came out a year or two before Kodak debuted the disc cameras. Anything with “disc” in the name was new, high tech, and desirable in the early 1980s, so Kodak rode the coattails of Sony and Phillips with their heavily advertised “disc” products.

I’ve often thought a digital camera with a design similar to the Kodak disc cameras would have been great—flat profile, decent non-protruding prime lens with an f/2.8 aperture, optical viewfinder, and shutter button on the front of the camera.

Thanks for sharing your story, Aaron!

Where the disc format had an edge over 110, despite having a smaller negative, is that the ESTAR base of disc film was incredibly flat and was always sharply in the focal plane compared to 110 (and even Instamatic 126) where the film could wiggle around going in and out of the focal plane resulting in blurred images, but also the Kodacolor HR and later T-Grain films had much finer grain than anything available in 110 at the time.

As for your wish for a modern version digital camera with a flat profile and non protruding high speed lens, you’ve basically described a smartphone! Some phones have buttons on the side, front, and many can be activating using your voice so you don’t even need a shutter release at all! In fact, many smartphone lenses are faster than f/2.8. I think the one on mine is f/1.9.

Fair point about the similarities of the smartphone to the disc cameras, although I’ve not yet seen a smartphone with an optical viewfinder. But then again I’m not sure how much it matters. I have a DSLR and hardly shoot it any more, as my smartphone is a much more convenient tool for making digital images than the DSLR.

You’re right that simplified and easy to use 35mm cameras captured the market, but disc film would have survived if Kodak hadn’t been so greedy.

I managed a photo lab in the early 80s, and the biggest problem for 35mm was camera loading. We’d regularly get blank rolls developed because the film leader never got attached properly to the take-up spool in the camera. This has happened to everyone at some point, but was especially frustrating for people who just wanted to take pictures and not fool around with the camera. The 126 and 110 cartridge films were great for those people, but size does matter. Kodak charged the same price for 126 and 110 cartridge film, but you got far less film in a 110 cartridge compared to 126. 110 film sold since the cameras were smaller, but the image quality was much worse. It was a trade-off that less demanding consumers were willing to make. The big mistake with disc film was to make it dramatically smaller than 110, and also make it more expensive. A cute trick if you can get away with it, but Kodak didn’t. A disc camera wasn’t any smaller or more convenient than a 110 camera for all practical purposes, and the image quality was certainly no better, and likely worse. The value for money equation just didn’t work out. Kodak made the same mistake with APS. Lots of new features, but a smaller image format and less film for your dollar. If APS had been designed with the same image size as 35mm it might have been a winner, but no, Kodak had to try the same scam again. 35mm survives since bigger is always better for film.

I agree with your analysis of the APS format. I think many of the features, like encoding exposure information on a strip, were clever. But, as you said, smaller piece of film at a similar price to the 35mm format. Consumers were not impressed.