Automation is coming!

In the decade after World War II, many of the world’s biggest economies were advancing technology at a fast pace. The United States and the Soviet Union were deep entrenched in a space race to explore the moon and our solar system. People fantasized about flying cars, space travel, and personal robotic assistants.

Soon, it was thought, automation would give us artificial beings that would be able to drive us around, clean our houses, and cook our meals. But not everyone was so excited about the prospect of automation as tales of “machines gone wild” dominated science fiction books and movies, blue collar factory jobs were disappearing at an alarming rate due to automation as the jobs that often required a team of several people to accomplish could easily, and cheaply be replaced by a machine. Strangely, these are concerns that we still have today, as more and more tech companies are investing in AI that can do everything from generating faces of people who do not exist, to legally representing us in court. Don’t worry though, this article is not about that kind of automation, rather an automation that had been rapidly becoming part of photography during the middle of the 20th century.

This week’s Keppler’s Vault takes a look at two different articles, both from Popular Photography. The first is from the October 1958 issue and explores the idea of automation in photography and what it might look like, and the second is from November 1959 which reviews 4 different “Electric Eye” cameras whose inclusion of “automatic exposure” was one of the hottest topics of the day.

When you think of automation in a classic film camera, what do you usually think of? Auto Focus? Yeah. Auto Exposure? Of course. The inclusion of these features in modern cameras was a big deal, and with each new feature, further made photography more accessible to novice and beginning photographers. But are these the only kinds of automation seen in cameras?

The first article suggests that automation was a far older concept than what people thought of it in 1958 when the article was written. If you were to compare a current 1958 SLR or rangefinder camera to that of a glass plate studio camera from the early 20th century, that SLR or rangefinder has a lot of automation already.

Take the film advance lever (or knob) for instance. On a modern SLR, each time you advance the lever, the film gets advanced to the next frame and automatically stops so that you don’t go too far. The exposure counter automatically goes up (or down depending on camera) by one to indicate another exposure has been used. Open the film door, and the exposure counter automatically resets. The shutter is automatically cocked and ready to be fired. When you press the shutter, the lens diaphragm is automatically stopped down to your chosen f/stop, the reflex mirror automatically flips up and out of the way, the shutter fires, and immediately after, the lens diaphragm automatically reopens, and the mirror automatically flips back down. Eventually cameras would automatically load and rewind film for you at the beginning and end of a new roll of film.

On rangefinder cameras, many models featured automatic parallax correction in which the frame lines in the viewfinder would move to represent a correct image at close focus. Interchangeable lens cameras had automatically adjusting frame lines when lenses of different focal lengths were attached. And although it’s a bit of a stretch, early rangefinder cameras were often heralded as “automatically focusing” because the rangefinder guaranteed that the lens would always be automatically set to the right focus distance.

In the simple process of moving the film advance lever and firing the shutter, all these things automatically happen, yet at one time, each of these features was an extra step. Lenses needed to be stopped down manually, film release catches needed to be manually released, reflex mirrors remained in the up position blocking light from entering the viewfinder. Each of these features that upon their release, was another step towards automation.

This first article makes a claim that a recent survey revealed only a small percentage of those who want to take pictures, have cameras capable of high quality results. The reason for all these low quality box camera users, wasn’t merely the cost of owning an expensive camera, rather the resistance amateurs and novice photographers had towards the painful process of exposure calculation of shutter settings, f/stops, and film speeds. It was thought that if a camera could automatically calculate exposure and eliminate this process, that this would open the door to higher quality cameras and photography to the amateur market.

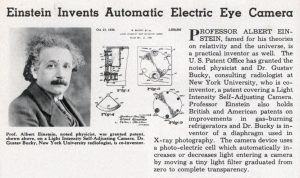

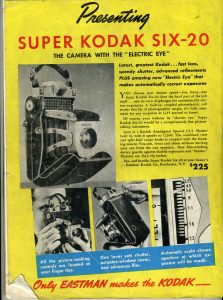

Automatic exposure was not unheard of in 1958 when this article was written, as it mentions the AGFA Automatic 66 from 1956. Albert Einstein actually patented an early form of electric eye automatic exposure as far back as 1936, with the first camera to have it, the Super Kodak Six-20, following two years later. Both of the AGFA and Kodak cameras were expensive and produced in very small quantities, so the average Pop Photo reader from 1958 would be forgiven if the concept was still foreign to them.

While they would had no way of knowing it when this article was written, they were right. Within 12 months of this first article, an onslaught of auto exposure (or electric eye) cameras would hit the market, and by the end of the next decade, automatic exposure would be a standard feature on nearly every camera sold.

Thirteen months after the first article was written, Popular Photography revisited the topic of auto exposure cameras, and took a look at four current cameras all with electric eye automatic exposure. The four cameras were the Bell & Howell EE 127 (which they strangely refer to as the ‘Infallible’), Kodak’s Automatic 35, Revere’s EE 127 Eyematic, and the AGFA Optima. I’ve had the pleasure of handling and reviewing every one of these cameras (I did the Kodak Motormatic 35 which is an identical camera, just with motor drive, and the Revere is in my “to review queue”) so it was with great fascination that I read what these photographers had to say.

I’ll spoil the surprise for you and say the feedback was positive across the board. Each of the photographers admitted great skepticism about the technology, but cautiously put them through their everyday paces, using them on assignment, in studios, and for casual photographs. Their conclusions were that although the cameras lacked “pro” features and had some definite limitations, when used within those limits, exposure automation worked with considerably accuracy.

The biggest limitation was that the large selenium cells could only detect an average reading of light, and was easily tricked in high contrast situations or in which there was heavy background light such as someone standing in front of a window. But when used within each camera’s strengths, the results were quite good.

In his test of the Revere EE 127 Eyematic, Peter Gowland mentions handing the camera to a 6 year old child, who didn’t even bother to focus, he simply pointed it at two of his friends and snapped away. When the photos were developed, the child’s photos all came out properly exposed and in focus. If that’s not a validation of the technology, I don’t know what is!

Of course auto exposure wouldn’t be the end to automation as cameras have continued to advance beyond even the wildest dreams of anyone in 1958, but many of today’s innovations border on the line of gimmicky, whereas the age of the “Electric Eye” was truly a game changer.

All scans used with permission by Marc Bergman, 2019.

As you indicate, one of the coolest things about ‘automation’ in cameras (and other things too) is the wide variety of meanings that the word took on. In the Rollei Automat, it meant that the mechanical frame counter reset itself to Frame 1 without having to line up a number in a red window… but the camera also featured coupled film wind and shutter cocking, and automatic parallax correction in the viewfinder. The Ansco Automatic Reflex a decade later had NONE of those features but was still called “automatic”, I guess just on the basis of having a (manually reset) mechanical frame counter. A few years later, the hot item was automatic lens diaphragms, and then instant-return mirrors, in SLRs. You can walk this all the way back to Kodak’s “You push the button, we do the rest” for their first box camera. To claim something as “automatic” today, you’d probably have to be referring to the camera wirelessly uploading your image files to the cloud.

Very true, Rick! I had actually thought of going through a whole list of every “automatic” feature a camera has claimed to have, but then I thought I would be getting away from the spirit of these Keppler’s Vault posts, which is to highlight the original articles themselves. Maybe that could be a whole separate article!

Nothing on the Konica Autoreflex, which changed the 35mm SLR territory for a time, championing a mechanical, shutter-speed-priority, automatic metering just a whisper before electronic systems appeared. (The original even featured “in body half- and full-frame format selection.”) I did wonder who would buy a non-through-the-lens-metering 35mm SLR, but I did see them in use in the late 1960’s. Later versions did adopt througth-the-lens metering, but by then electronically timed cameras were all the rage. (I was bemused, but not interested, since the Nikkormat FTn still worked just fine for ordinary use.)