Are you ready for some football?!?!

This “battle cry” has long been a staple of Monday Night Football, the original prime-time slot for American professional football in the United States. These days when you want to watch a football game, you get to see it on large 4K high resolution televisions, made up of several dozens of camera angles from all over the field, cameras on cables flying above the field, blimp cams, goal post cams, and sometimes even helmet cams.

If you miss the game on television, you have countless options of streaming websites, apps, and whole television channels dedicated to football to give you up to the minute stats, replays, and commentary.

Of course, it wasn’t always like this. Prior to the days of the internet and television technology, if you wanted to watch a game, you either had to go there, or wait for the Sunday paper to read about local and national games.

One of the many things I love about collecting and shooting old cameras is stepping into the shoes of photographers from an early age when cameras didn’t give instant results on an LCD screen or could be instantly uploaded to social media and shared with the world, seconds after the photos were taken. Photography used to be slower, more deliberate, and more thoughtful.

When I saw this article from the December 1949 issue of Modern Photography which gave a behind the scenes look at the newspaper staff of the Des Moines Register, I was initially fascinated, then horrified. Not horrified for any bad reason, but that the process was as complex as it was. If there has ever been an article that makes me appreciate the speed and conveniences that photography has today, it’s this one.

Author G. W. Van Citters takes you through a typical Saturday cycle of photographers flying out to a regional football game and how they capture the action and get it ready for publishing and onto customer’s doorsteps Sunday morning.

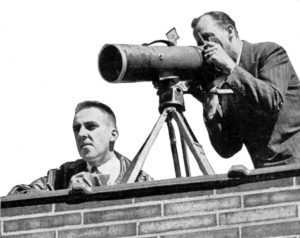

The article mentions a variety of “howitzer” and “machine gun cameras” that are used for this ritual. The howitzer appears to be some type of modified Graflex Speed Graphic with a long telephoto lens on it that benefits from the higher resolution of sheet film for maximum detail. The machine gun cameras are specialized Bell & Howell Eyemo 35mm motion picture cameras with a modified shutter that fires at 1/375 instead of 1/30 to capture fast action sequences without motion blur.

In order to capture properly exposed images that are in focus, the photographers memorize the dimensions of every stadium that their teams would play in. Assuming a brightly lit Saturday afternoon, they can estimate exposure using 100 speed film, and knowing the distance from the press box to each corner of the playing field, they can use depth of field to their advantage so that the cameras are pre-focused before the shot.

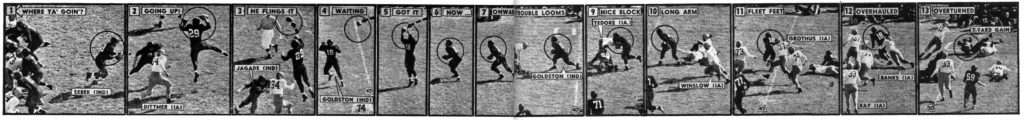

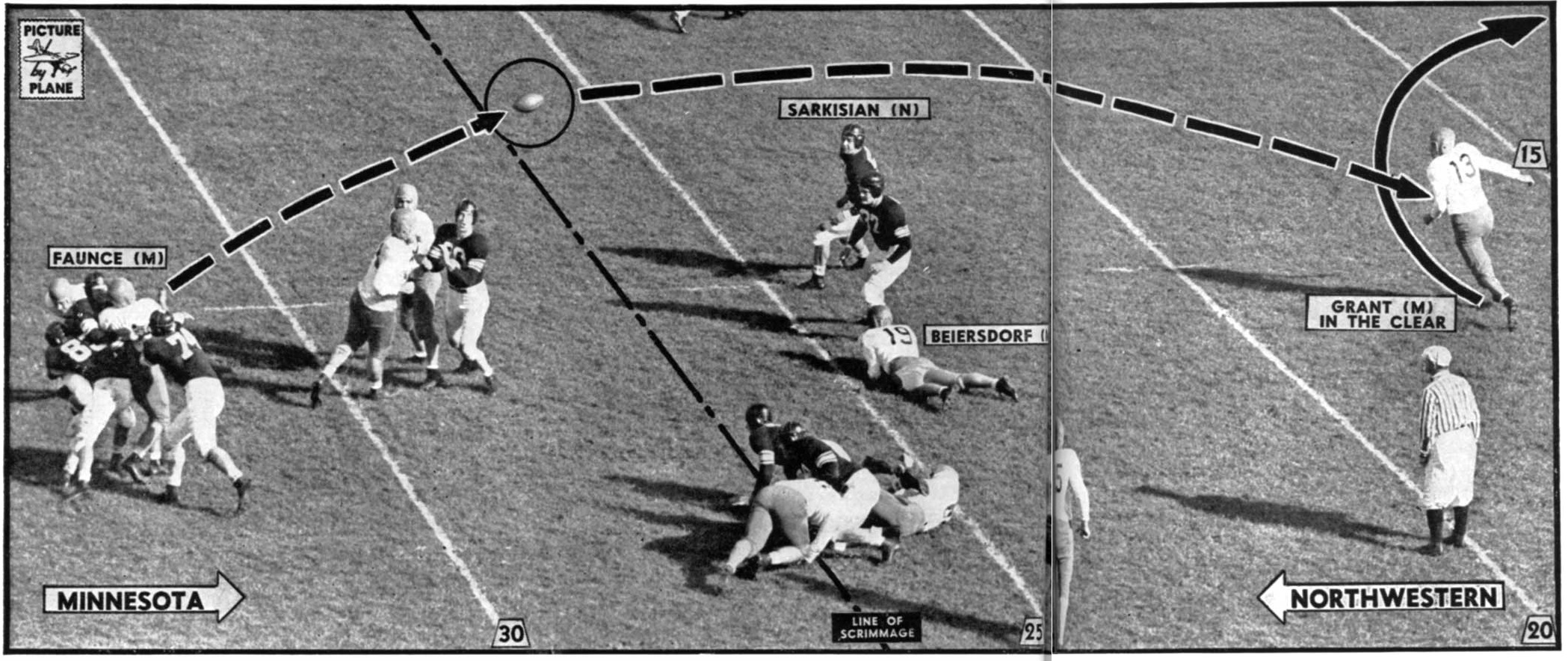

The machine gun camera follows every play for the entire game, but isn’t continuously firing. A spotter works with the photographer taking notes of what’s happening with each sequence of shots taken, so that the editors back at the paper can piece together the images with a description of what’s happening. Since the camera isn’t firing when no action is happening, the photographers point the camera at the scoreboard after each play to get a time stamp of when those shots were made, to more easily match up the photos with the notes from the spotter.

The howitzer photographer has a much more elaborate shooting process which the article describes as:

At the end of each play, he inserts his slide, withdraws his holder, zips his focal plane shutter to “0,” focuses on the scene of the next play, cocks his shutter, inserts his holder, withdraws his slide, puts his eye to the viewfinder, follows the play and trips the shutter at the climactic instant, whereupon he repeats the entire cycle.

Simple right?! It’s one thing to thoughtfully follow this process in a controlled environment like a studio or when shooting landscapes where things can be slowed down and the photographer works at his own pace, but to have to do this quickly, in the middle of a football game, over and over, hoping to capture just the right “climactic instant” gives me anxiety even typing this out!

The instant the game is over, the press team jumps back on a plane and heads back to Des Moines where the film immediately heads to the dark room for development. The 35mm film is developed on large reels and afterwards dries on a custom made contraption made up of old bicycle wheels.

This process begins around 4:15pm and is complete by 4:45pm at which point the prints are sent to engraving by 5:40 where artists draw additional artwork onto the negatives which help to tell the story of sequences of shots made to help the reader understand what they’re looking at. The artwork and text of the articles is completed by 9:20pm at which time presses start to roll printing out tomorrow morning’s paper.

So next time you watch a sporting event and see instant action and live feeds from sportswriters from all over the world creating content for you to read and look at seconds after it occurs, think of these guys and the literal hoops they had to jump through, to bring details football action to Sunday morning Iowa readers in 1949!

Read the entire “Flying Football Cameramen” article in your browser below. If you wish, there is a download link in the control panel at the bottom of the article.

All scans used with permission by Marc Bergman, 2019.

WOW, what a trip down memory lane this story is! My dad was a magazine editor; I well recall him during the late 1950s, bringing home 8×10 b&w glossies rubber-cemented to cardboard, taping tracing paper over them, and supplying both crop marks and captions in grease pencil, for return the following morning to the pre-press guys, who’d shoot the process negatives for the stripping department.

.

In my own case, I was the high school football team’s eyeglasses-wearing skinny mascot, hauled here and there throughout the district in the team bus, setting up tripod and Penta J mounted to a refractor telescope with a home-machined adapter (Yeenon did not yet exist … HA). They’d get me up on the roof of the press box and I’d shoot the action. The telescope served as about a 500mm lens with a single aperture of about f11. Follow-focus was a true challenge. Tri-X shot at ASA 1200 and souped in Acufine allowed me to use a fast shutter speed. “These kids today, they have no idea what photography was like when WE were young … !”

I am really happy you enjoyed the article Roger. I love football almost as much as photography, so it was a thrill for me to find an article that crosses off two interests of mine, but for it to be a trip down memory lane for someone like yourself, makes it all the more relevant!

This is a great article about the way it used to be when shooting sports. I shot about 500 NFL and 2000 MLB games in my career from 1983-2016. I loved hearing the stories of how the old shooters would cover games. Unfortunately a lot of those guys have passed now.

Dan, after reading your comment and speaking to you in person, I am in awe of the things you must’ve seen. I’d love to one day see a gallery of sorts of images you’ve shot!

In the early 1960s I shot Penn football, mostly at Franklin Field with a Speed Graphic 4×5, a Sawyer’s Mk IV TLR (127), and, later, a Minolta SLR. At halftime all the press guys were given Kraft crackers and cheese! Only got run over by a player once. Football was very challenging to shoot because the point of focus moved so quickly. Good thing I didn’t know about auto exposure, autofocus, motor drives, and zoom lenses.