When George Eastman released the first Kodak camera in 1888, it came preloaded with a long roll of photographic film that could take 100 images before it needed to be sent off for development. The idea that you could have a camera loaded with film that didn’t require separate glass or metal plates to be inserted and removed after each exposure must have seemed like future technology for photographers at the time.

After that first Kodak, roll film cameras became more and more common with nothing more than a simple twist of a knob (and later a lever) to prepare for your next shot. It would take over 45 years before any meaningful advancements were made in “film transport” technology with the release of the Berning Robot I.

Originally designed by Heinz Kilfitt, the design for the clockwork powered Robot was sold to Otto Berning & Co. and produced starting in 1936. Over the next several decades, cameras from the Robot series were used by professional photographers, in aerial and industrial applications, and even in traffic cams as the cameras could be used to fire off a sequence shots quickly and without user intervention.

Another early camera that came with a clockwork film transport was the innovative Bell & Howell Foton from 1948 which used a shutter inspired by Bell & Howell’s experience with cinema shutters to create a rapid fire clockwork film transport and shutter that could shoot as many as 4 exposures per second.

Later advancements in automatic film advance came in the form of external motor drives. The first was the KW Praktina from 1952 which had a provision on the camera’s base plate that could be coupled to a wind up motor drive and later a battery powered electric drive. Without the motor drive, the camera would have to be wound by hand, but with the motor drives, high speed continuous photography was possible.

The following video shows how the wind up motor works (and sounds) on my Praktina FX.

The Praktina’s motor drive coupling heavily influenced later SLRs such as Nippon Kogaku’s Nikon F, which itself influenced many other SLR makers, but it would be another East German camera maker who would make the first camera with a fully integrated electric motor.

The Pentacon Prakti made it’s debut in 1960, only months ahead of an onslaught of other motor drive cameras. Unlike the Berning Robot’s spring wound motor, the Prakti had an electronic motor, powered by two AA batteries. Although benefiting from not requiring any effort from the photographer to wind up the camera, Pentacon’s electric motors were incredibly loud, slow, and problematic.

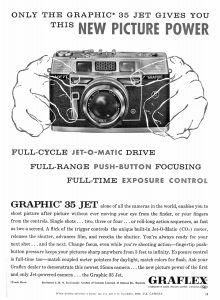

Kodak and several other companies like Fujica, Canon, and Kowa took a more conservative approach with a wind up motor similar to the Berning Robot, but perhaps the strangest implementation of auto advance was in a short lived camera built in Japan by Kowa for Graflex, called the Graflex Graphic 35 Jet.

Building off the popularity of the Cold War “Space Race” and Americans infatuated with jets and rockets, the Graphic 35 Jet used specialized bottles filled with compressed carbon dioxide, similar to those used in air rifles to power a mechanism that would advance the film and cock the shutter after each shot.

This so called “Jet Powered” camera could be fired as fast as 4 exposures per second and the sound of the compressed gas operating the film advance is said to sound like that of a bullet ricocheting. As ambitious as the design was, it proved to be very unreliable as the o-rings needed to maintain the pressure from the bottle would fail quickly. Combined with a high price, the Graphic 35 Jet did not sell well and in an effort to move inventory, Graflex modified the remainder of the unsold cameras to remove the Jet powered parts and sell the camera with manual advance only.

By the mid 1960s, whether it was by a wind up spring or electric motor, automatic advance cameras were common and the feature was increasingly favored by professional and amateur photographers alike.

This week’s Keppler’s Vault takes us to the August/September 1962 issue of Camera 35 magazine which covered The New Revolution of Auto Advance Cameras. The article repeatedly refers to these new automatic cameras as “sequence” cameras in that they are capable of quickly shooting a rapid sequence of shots to convey motion. While that was certainly true, this is the only instance of the term “sequence camera” I’ve found while collecting, suggesting it was an early term that never caught on.

The article correctly predicts that sequence cameras would have the greatest impact in both sports and wild life photography and also in new experiments such as the image above which shows a sequence of shots of a lady walking, all edited together into the same image.

Although it wasn’t written as a prediction, the article cautions that the added convenience of quicker auto advance cameras should not “be an excuse to shoot up a storm in hopes of getting one good shot.” Little did they know in 1962 that half a century later, this practice, sometimes referred to as “spray and pray” or “machine gunning” has become common in digital photography in which the shutter release is held down for a rapid fire of shots in the hope of getting one good one.

The rest of the article goes over the differences in the different designs of cameras, commenting that with spring wound cameras, the speed at which the system operates slows down as tension starts to decrease. Also, that the speed of the film transport changes depending on if the camera is loaded. A test of a camera’s speed without film in it will always be faster than with film in it. While this probably seems obvious to most, it was often a misleading way manufacturers boosted the claimed speed of their camera.

In total, 12 cameras are represented in the article with a short paragraph or two about each model, how it works, and it’s price. Some, like the Leica M series and Nikon F use auxiliary motors, while others have built in motors. The most interesting to me are the Graphic 35 Jet which I discussed above, the half frame Yashica Sequelle, and the Tessina mini 35mm TLR. Missing are compact wind up models like the GOMZ Leningrad which would have likely not been available to an American magazine at the time and models like the Fujica Drive, Canon Dial, and Ricoh Hi-Color 35, none of which had hit the market at the time this article was written.

All scans used with permission by Marc Bergman, 2020.