You would assume that any magazine article telling the story of one of the most famous street photographers of all time would mention his name in the title. This week’s Keppler’s Vault about Arthur Fellig, better known as “Weegee” is the oldest article I’ve ever featured and is from the December 1937 issue of Popular Photography, and is merely titled “Free-Lance Cameraman”.

In my research for this post, I could not find any information about Fellig prior to December 1937, so it’s very likely that this article is the first to alert the photographic world to Weegee, who is well recognized as one of the most well known freelance street photographers of all time.

Arthur Fellig was born Ascher Fellig on June 12, 1899 in what was then Złoczów, Austria-Hungary, but now part of Ukraine. After emigrating to the United States in 1909, his first name was changed to Arthur. Growing up in New York City, Fellig took various odd jobs, one of which was as an assistant to a commercial photographer where he learned his way around a darkroom. This experience came in handy as in 1925 he was hired by Acme Newspictures who would later become UPI, as a darkroom technician.

Fellig would work for Acme for eleven years where he observed the ins and outs of professional photographers, picking up skills that would eventually serve him well later in life. In 1935 he would leave Acme to pursue a full time career as a freelance photographer.

Arthur Fellig understood that in order to make a living shooting photos, he needed to be able to sell them. In order to sell them, he knew that he couldn’t step on the toes of the pros who worked for other news organizations and the big papers. Back then, most big time photographers had little respect for freelancers. They were considered thieves, as each time a freelancer sold a photo, that was one less the pro could sell.

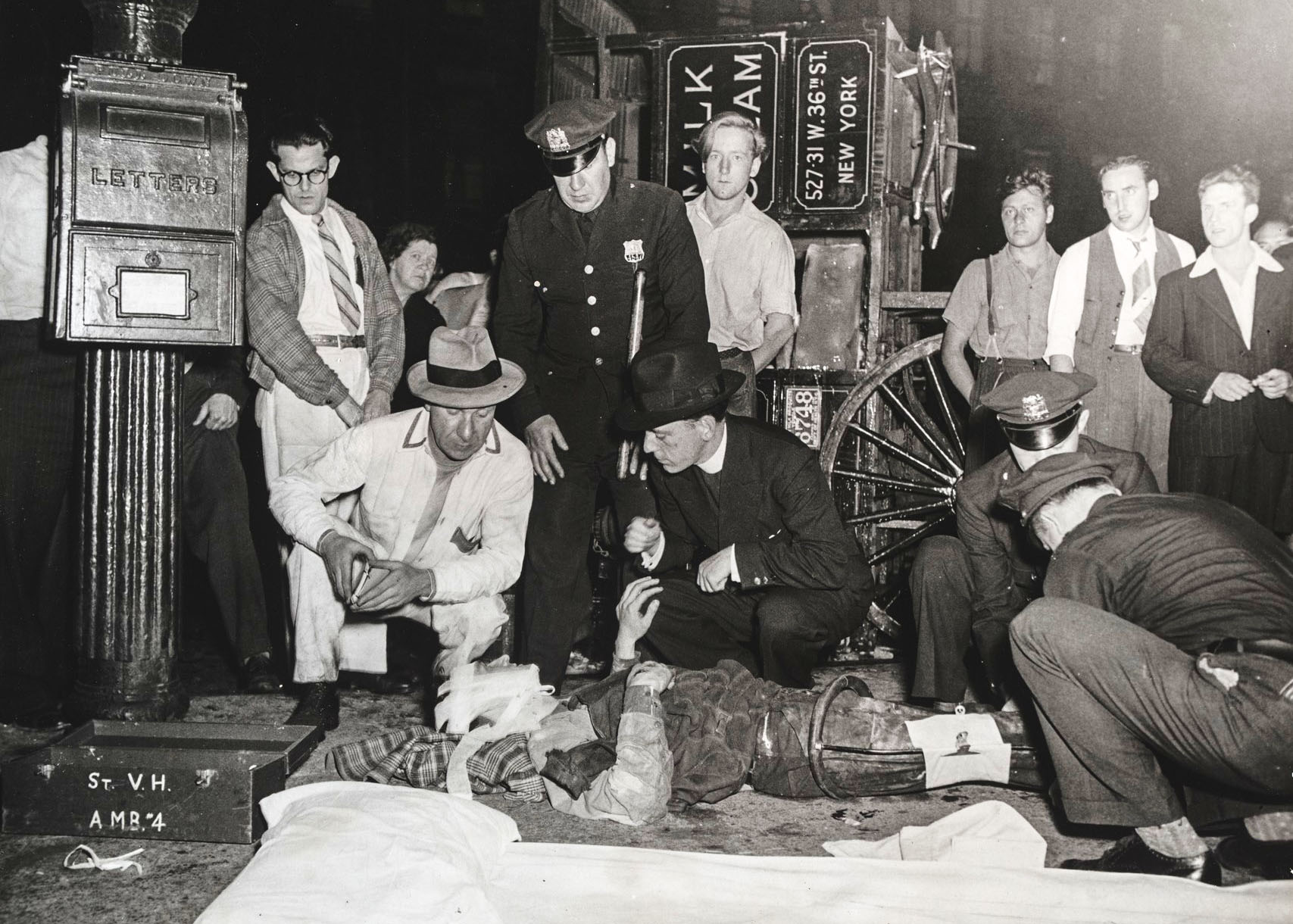

Fellig worked around this by working almost exclusively at night. He knew from his time working at Acme that many of New York’s papers did not keep photographers working the night shift. Some did, but for those that didn’t, if a big story hit, they’d have to get their day photographers out of bed, and by the time they’d get there, it was usually too late. Fellig saw this as an opportunity by being the first on the scene getting images the other papers couldn’t get and then selling them back to them in time for the morning edition. This helped win him some respect as he was taking the jobs many weren’t willing to do.

Shooting exclusively with a 4×5 Speed Graphic with a Tessar 3.5 lens, Fellig shot most of his shots at f/16 and the focus fixed at 10 feet. Later in life, he would popularize the phrase “f/8 and be there” describing that if you set your camera to a safe setting that offers you the best chance at getting a good photo, you can spend more time thinking about your shot, rather than the camera.

Fellig’s Speed Graphic was standard fare among press photographers of the era, it was neither his equipment or his technique that brought him the most success, it was his understanding of how the system worked, and that the best prints to sell are ones that tell a human story.

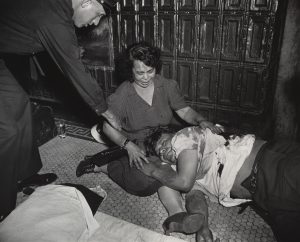

While a dramatic shot of flames shooting out of a burning building might be exciting to see, the images that sold best were ones of the people affected by that fire, perhaps with ash on their face, and a glazed look in their eyes as they watched their belongings burn.

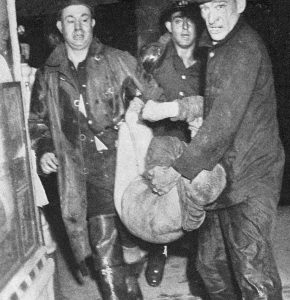

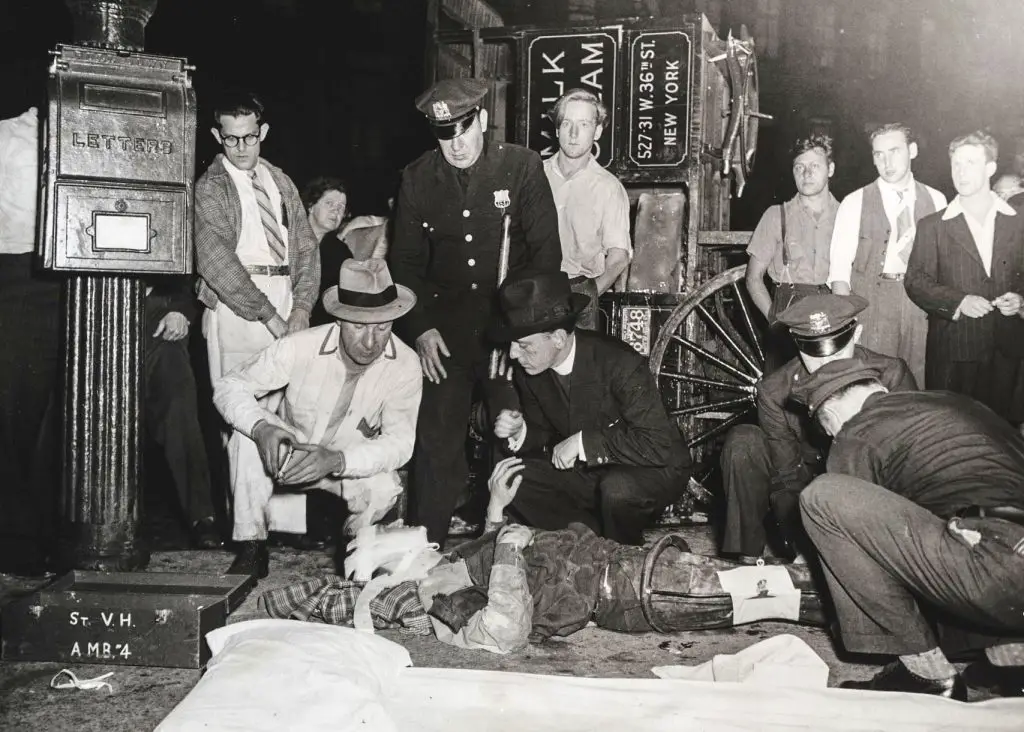

If you’re shooting a vehicle accident, don’t just shoot a crumpled vehicle, try to get it’s driver in the image too, maybe even with some blood dripping down their face. Fellig remarked that getting pictures of pretty girls sold well, and if you could get one crying, it was worth even more. Connecting people to the images he shot was one of the secret’s to Arthur Fellig’s success. Blood, gore, and occasional nudity were all frequent elements of Fellig’s work. It was raw and shocking, but it sold.

One of the ways Fellig was able to get to the news so quickly was by gaining favor with the NYPD. Early on, Fellig would rent a hotel room across the street from a local precinct and wait until they responded to a crisis and follow them. Arthur Fellig used his friendly personality to great effect, getting on the good side of officers, being respectful to their crime scenes, and in some cases doing favors like shooting baby christenings and police outings and picnics. If he got a good shot that an officer liked, he would make multiple prints for them for free. Eventually, the NYPD would grant him access to their radios, allowing him to listen in on private police channels, further giving him an edge on getting to the scene first.

Shooting crime scenes, many of Arthur Fellig’s best images were some of the most gruesomest. Images of murders with blood splattered all over the wall, crumpled vehicle wrecks, and injured or dying people being carted off in an ambulance were favorite subjects for him to photograph. Arthur Fellig’s knack for getting the images he got so quickly earned him the nickname “Weegee” as his peers joked that he must use an Ouija board.

When this article was first published, Weegee was well known in New York City, but not elsewhere. His style of gritty street photography was not a common way to make a living and when Popular Photography first published this article, it likely was the average reader’s first glimpse into Weegee’s raw style.

By the early 1940s, Arthur Fellig became increasingly known by his nickname, even using it as a stamp to certify one of his photographs. He would stay active for the rest of his life, expanding into cinema photography in the 50s and 60s, and even appearing in a few movies.

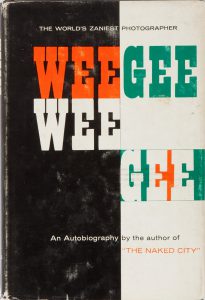

In 1961, his autobiography, “Weegee by Weegee” shared many of the stories of his life that he experienced while on the streets of New York. In his book, Weegee was very well aware of the myths surrounding him and his work, and his stories only helped fuel the imagination of those who wanted to know more about him.

Arthur Fellig would eventually pass away on December 26, 1968 but his photography continues to live on to the present day. Although there have been many street photographers in the years since, most of them were influenced in some way by Arthur Fellig. His combination of a knack for telling a story in an image, his friendly personality, and unique look, almost always sucking on a cigar make him exceptionally memorable.

All scans used with permission by Marc Bergman, 2020.

A great find…interesting that in the shot at the top of your post he’s wearing some sort of space helmet but also using a quite new-looking Nikon S2. Shot doesn’t appear in the 1937 article of course, but where on earth (or in space, for that matter) is it from?

The space helmet pic came much later when I was just looking for interesting pics of Weegee to supplement the article. I liked that one as it’s goofy, he’s still chomping on his cigar, and he’s holding a camera you don’t normally see him with. My guess it’s from the early to mid 1950s, well after the original article was written.

Thanks for this, really interesting post! I didn’t know this stuff about Weegee’s early career – it’s always interesting to see the hard work, ingenuity, people skills and various other not-directly-photography-related qualities that go into making a top photographer.