Kodachrome could very well be the most commercially successful film stock of all time. Not only was it in production for more than half a century, it inspired a 1972 song by Paul Simon, a 2017 movie starting Ed Harris, and also had a Utah State park named after it. Upon it’s discontinuation in 2010, the photographic world collectively mourned it’s loss.

I am sorry to say that never in my life did I have the experience of shooting Kodachrome. As a kid growing up in the 80s, my parents only ever used regular color negative film or Polaroid instant cameras. I do not remember ever growing up with a slide projector or having any use for slide film of any kind and by the time I fell in love with film again in 2014, it was already too late for me.

This week’s Keppler’s Vault is a special 19 page feature article from the September 1985 issue of Modern Photography, celebrating Kodachrome’s 50th anniversary. This article is one of the most detailed and comprehensive I’ve ever discovered in my search for these Keppler’s Vault articles, and I really hope you all take the time to read it in it’s entirety.

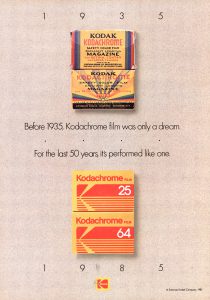

It starts off as most of my articles do, covering a bit of the history starting with the official announcement on April 15, 1935, showing images from magazine articles from the 1930s when it first debut, along with reactions from magazines such as LIFE. There’s even a little bit about pre Kodachrome color films such as Lumiére Autochrome, AGFAcolor, and something called Dufaycolor.

The article then gets a bit technical, explaining how Kodachrome’s subtractive process works compared to additive processes that were common at the time. Later, it explains how Kodachrome was different from other films, and although they didn’t know this in 1985 when this article was printed, led to it’s discontinuation in 2010. The development process is wonderfully complicated and could only be done by Eastman Kodak themselves, and although I don’t understand much of it, I still enjoyed reading about it.

My best attempt at simplifying how it’s done is that most color negative and slide films have color pigments in the film itself that produce the various shades that make up a color image. With Kodachrome, the film is fundamentally a black and white film with separate layers that are sensitive to different colors of the spectrum. When the film is developed, the color is created by the development chemicals itself, and it is these chemicals that make Kodachrome what it is.

The reason no one has been successful at completely recreating the Kodachrome process today is that reverse engineering the various chemicals needed to produce an image are prohibitively hard. Just look at how difficult it’s been to reverse engineer Polaroid instant film. In the last 11 years, first Impossible, and then Polaroid Originals have come close, but still have yet to perfectly recreate the quality of original Polaroid film. The fact that they’ve come as far along as they have, suggest that it’s at least doable, yet apart from one hobbyist, no one seems to be making any progress with Kodachrome.

Perhaps it was Kodachrome’s difficult process that gave it a look that no other film had. Colors were vibrant, but not cartoonish, the tints of reds and greens weren’t as natural as real life, but not quite pastel either. Upon it’s release, the photographic world was stunned at the life like colors, and even conservative publications like the British Journal of Photography raved about the potential, calling Kodachrome revolutionary. The look of Kodachrome film is often associated with all mid century color film. Whether they realize it or not, when most people visualize what like was like back then in color, they often see it through the eyes of Kodachrome film.

When it was first released, Kodachrome was only available in 16mm, as a six layer emulsion with a RemJet backing, intended for motion picture films. The first still film Kodachrome wouldn’t be available until September 1936 when it was released in both Kodak’s new 135 daylight loading cassette and 8 exposure 828 roll film format. The speed of the first Kodachrome was daylight balanced at ASA 8, comparable to Kodak’s Panchromatic black and white film. An 18 exposure roll of Kodachrome 35mm film sold for $3.50 and $1.75 for the 828 version, both prices included development by Kodak. When adjusted for inflation, these prices compare to $65 and $32.50 respectively, an incredible amount for a single roll of film.

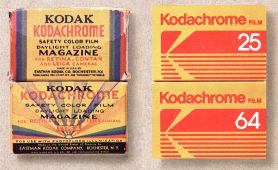

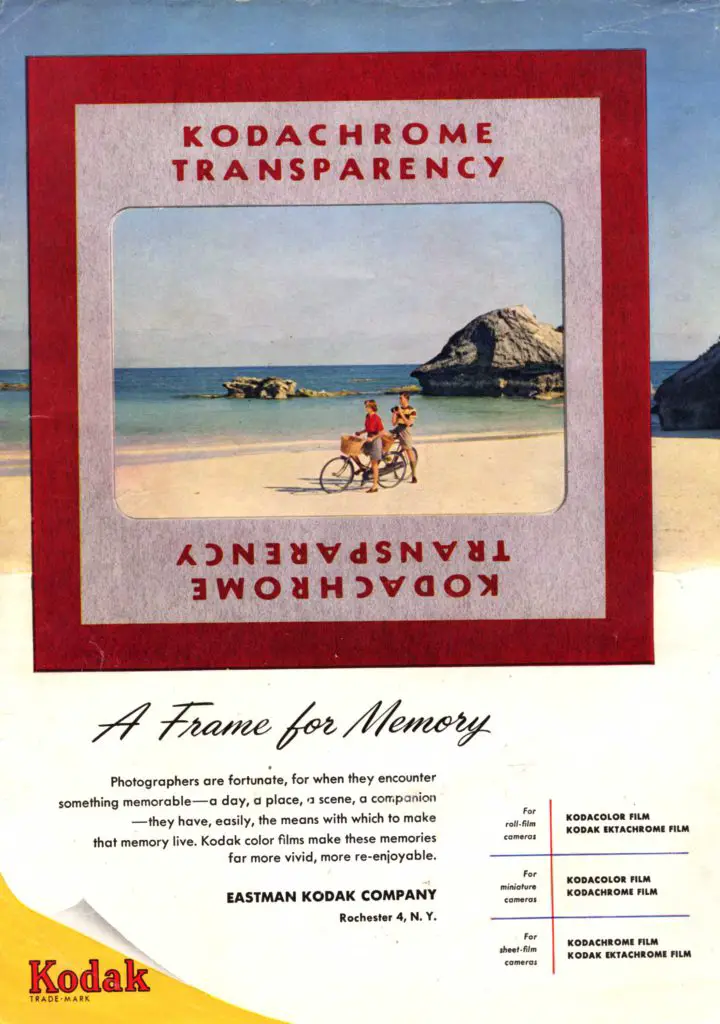

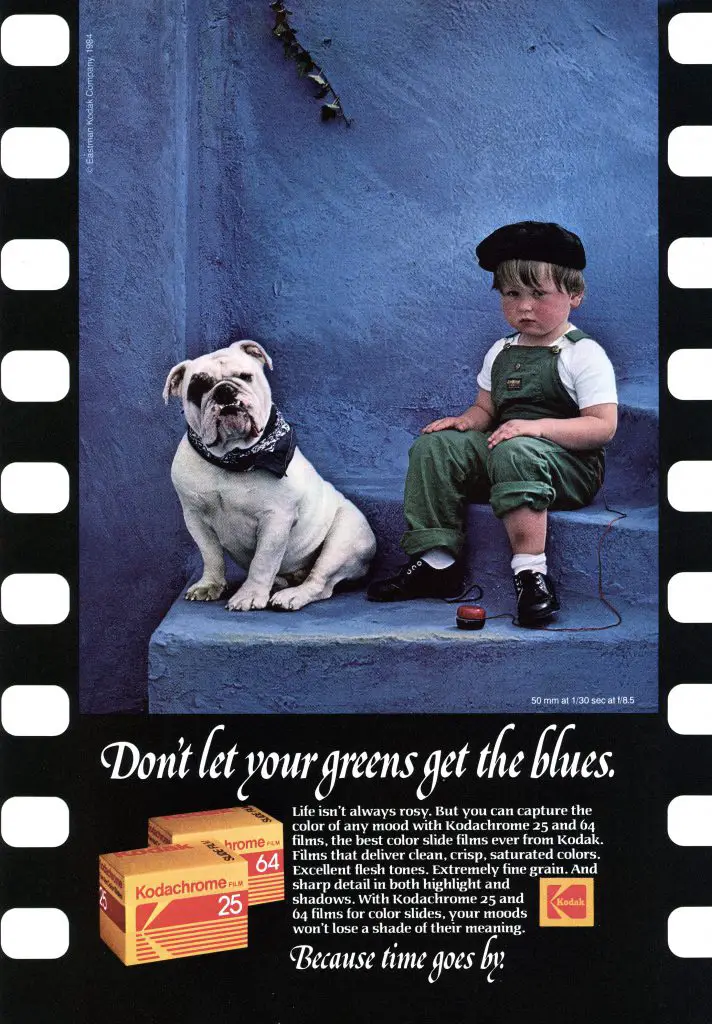

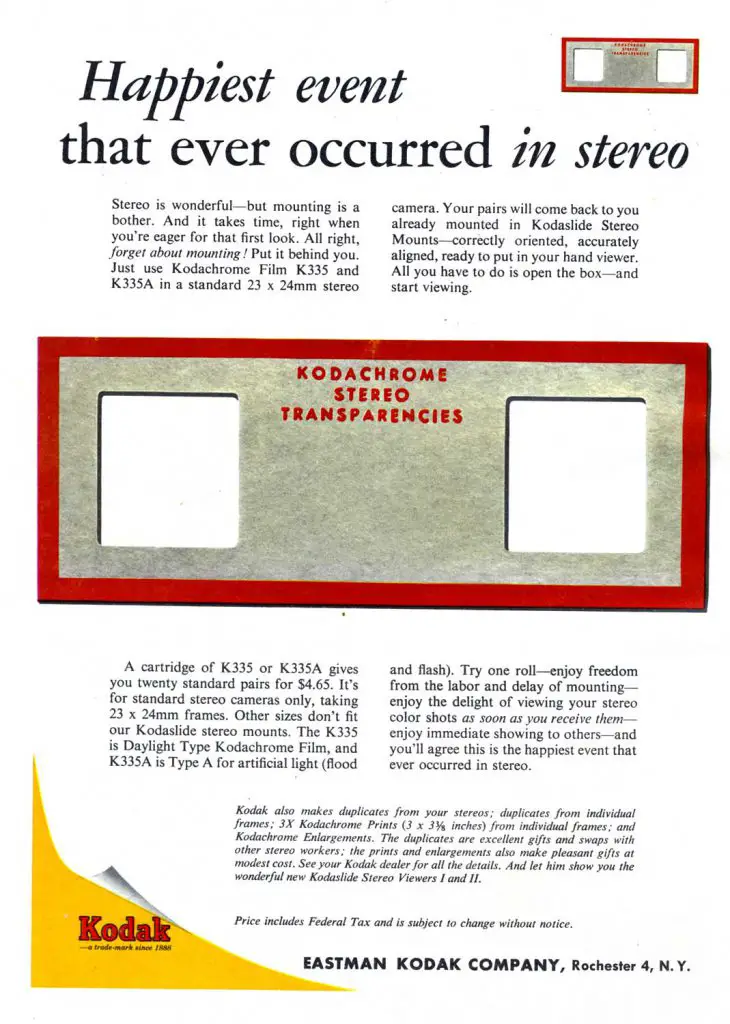

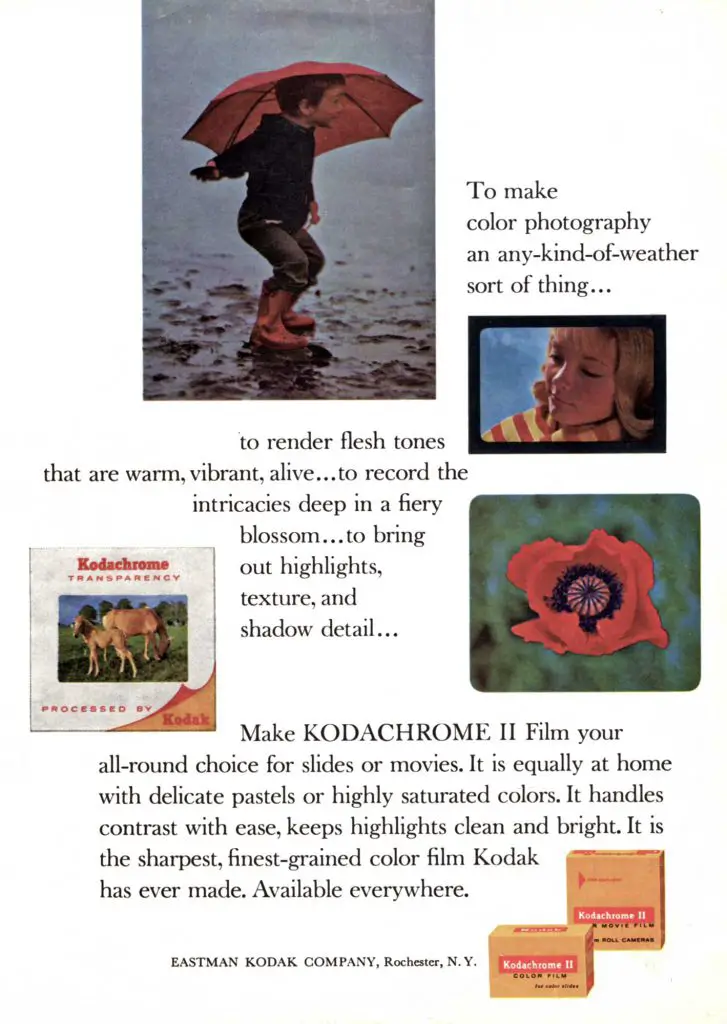

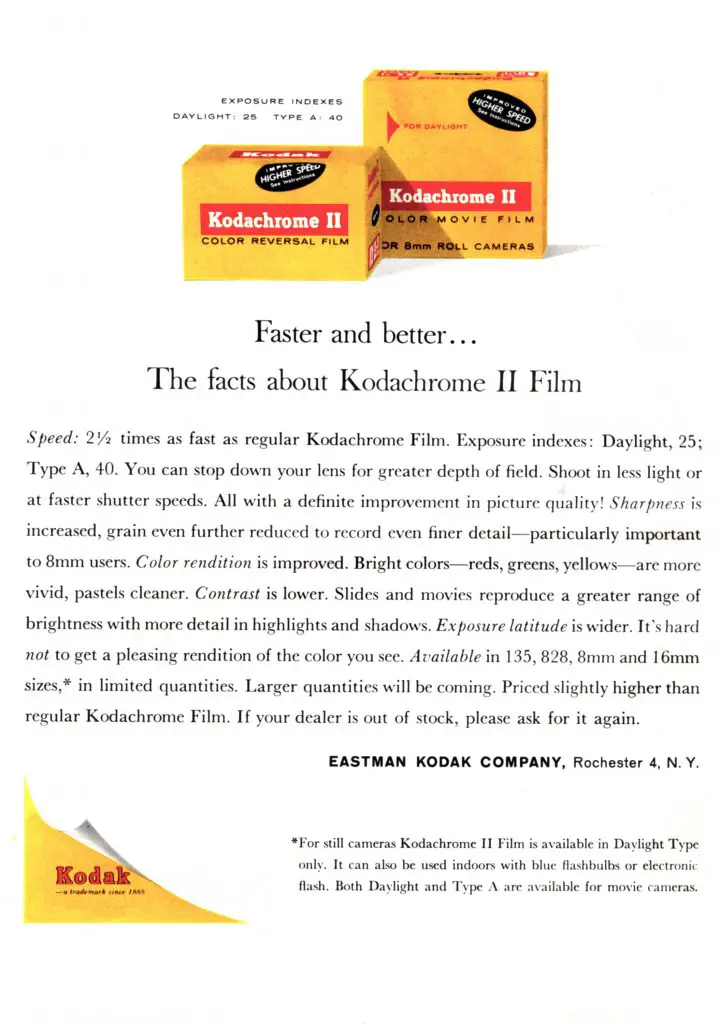

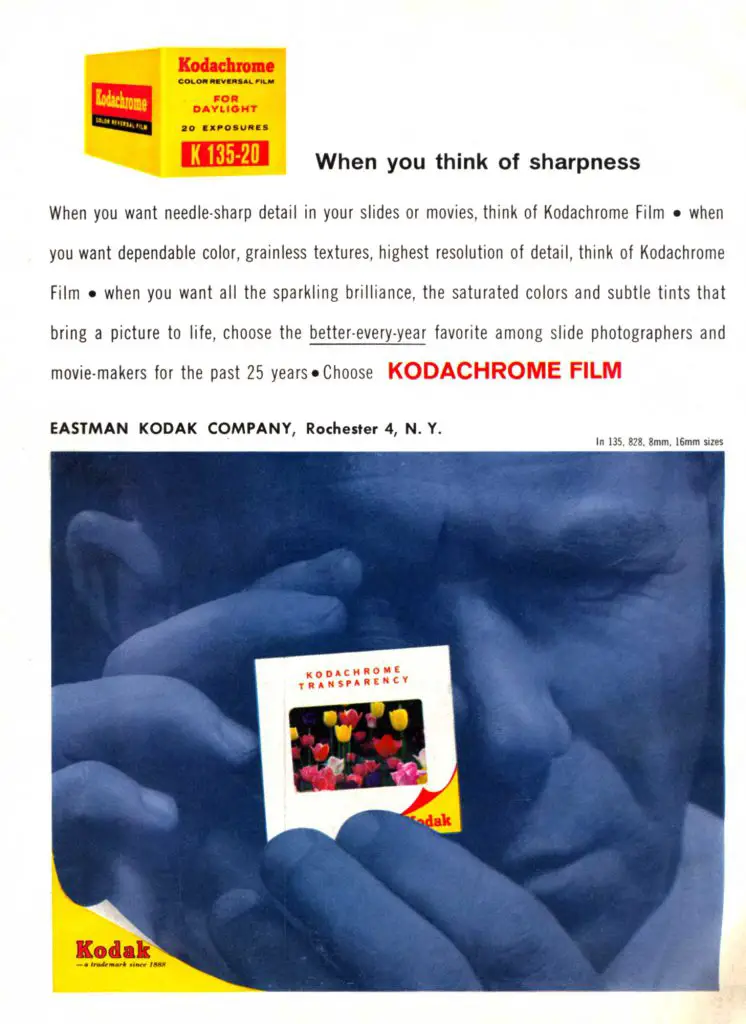

The gallery below shows various advertisements for Kodachrome throughout the 20th century, showing the different changes the film saw, from stereo slide mounts, faster speeds, and updated packaging.

There is a lot more to the article, talking about the early struggles with the film, variances in film speeds, and formats, along with Kodachrome’s comparison to other formats.

I wanted to include some sample images of Kodachrome slides, and whenever I take images I find online, I make an effort to contact whoever they belong to and ask for permission. The following collection of images appeared on an old website run by someone called Jim Hughes. These are likely promotional images he found elsewhere, but I am still going to include them with credit back to him, but if I ever receive anything from him or anyone else asking that I take them down, I will do so and try to find some other examples.

I often enjoy reading old articles like these where the editors make predictions for the future, and at the end of this article it correctly predicted that, “…ongoing progress in electronic images will eventually bring even this seemingly indestructible, landmark film to an end.” They were right, as 25 years later, as the digital era of photography saw a dramatic decrease in film use and sales, Kodak’s financial struggles meant that it was no longer profitable to continue making Kodachrome and it’s chemicals.

As an added bonus, here are two separate articles, both from early 1963 announcing the release of the much faster Kodachrome-X. It’s hard to remember today of a time when shooting color meant using film stocks no faster than ASA 10 or 25. With today’s digital cameras that can easily shoot color images with ISO speeds into the tens of thousands, when Kodachrome-X was released with a speed of ASA 64 it was a game changer for many people.

For one, it was now easier to shoot sports and other fast motion subjects as the speed of the film allowed for faster shutter speeds to be used, but also, it meant that more cameras could take advantage of color photography as the faster speed of the film lessened the requirement of fast lenses to capture the necessary amount of light for extremely slow films.

Although Kodak would eventually drop the “X” from the name and simply call the ASA 64 version of this film “regular” Kodachrome, the release of Kodachrome-X was a necessary and important milestone in the development of this film, allowing it to maintain it’s popularity for what would become another 40 plus years!

All scans used with permission by Marc Bergman, 2020.

Hey Mike, another great article, thanks for your effort! As a child of the 1960s Slide Nights are such strong memories for me, sadly back when I had the chance I never shot it, which is one of my biggest regrets now. It should be mentioned that Kodachrome became synonymous with the “National Geographic look” and after Kodak ceased production Steve McCurry of “Afghan Girl” fame turned to Kodak E100 VS which was produced as late as 2014, so although nowhere near the look of Kodachrome you will get images that are comparable.

Probably the best to see the look of Kodachrome is to examine the website, exhibitions and books released by The Anonymous Project run by Lee Shulman in Paris.

https://www.anonymous-project.com/the-project/

BBC Documentary: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LZHn8mCau6s

Books: https://www.editionstextuel.com/livre/the_anonymou_project

Mike, thank you for posting this retrospective on Kodachrome! I remember that issue of Modern, which I kept for many years. As for those Kodachrome images, they were from some Kodak public relations publication, but I can’t remember the date. The 4×5″ Kodachrome frame dates that example to the 1940s or 1950s.

Some of my dad’s 1944 Kodachromes: https://worldofdecay.blogspot.com/2019/10/from-archives-boston-massachusetts-in.html

An additional note: even the 35mm cardboard frames were the result of a lot of testing and refinement. The Kodak ones seldom opened or warped, unlike cheap competitor frames. The Kodak ones held the slide solidly. And to think, a machine did the cutting and mounting.

Oops, I forgot. A minor update about processing:

For many years, Kodak sold its film along with a processing envelope in which the user sent the film back to a Kodak laboratory. After some anti-trust lawsuits in the United States, Kodak had to separate its manufacturing from its processing. Some other companies offered Kodachrome processing in the 1960s, but I cannot remember exactly whom. As I recall, the alternate labs disappeared in the 1970s or maybe the 1980s. In Europe and Asia, Kodachrome film still came with the envelope, and the price included both film and processing by a Kodak lab (UK, Switzerland, Tokyo, etc.).

In the 1990s, Kodak introduced a compact processing system called the K-lab, which it hoped would help spur more companies around the country to offer Kodachrome processing with faster turnaround:

https://125px.com/docs/unsorted/kodak/tg2044_1_02mar99.pdf

The last lab on earth to handle Kodachrome was Dwayne’s in Parsons, Kansas (an independent lab, not Kodak). The last film is the theme of the 2017 movie that you noted above.