I still remember my first digital camera. It was a Toshiba PDR-M25, a 2.2 megapixel monstrosity that captured 1720×1200 pixel images on a SmartMedia flash card. I was the first person in my family to have a digital camera, and upon showing it off at family functions, no one cared about the crappy pictures it made, only that it didn’t need film!

The ooh’s and aah’s came every time I showed off the 1.5″ 61k pixel LCD on the back of the camera. People were amazed that not only could you see your images instantly after they were taken, but that if you didn’t like one, you could delete it without wasting any film. The thought that I’d never have to go to the Fotomat again and wait between 1 hour and 1 week to get my film back was life changing.

Almost overnight, I forgot about film. I shot thousands of digital images, but quickly outgrew that camera and upgraded to a Canon PowerShot S2 IS with 5 megapixels and a 10x optical zoom. Despite being only a couple years newer than that Toshiba, the Canon was light years better in every way. Images looked great, I loved the zoom, and all the shooting modes further wetted my appetite for photography.

I imagine my experience was like many others. Everyone used film cameras, until they didn’t. It felt like the digital revolution arrived with no warning and as soon as it begun, no one looked back. Film was dead.

The reality is, the swift change from film to digital didn’t happen overnight. In fact, the first shots in the digital war were fired in December 1975 when a 24 year old Kodak employee named Steve Sasson built the world’s first digital camera, using off the shelf spare parts he found at work. The camera used a CCD sensor that captured a 0.01 megapixel black and white image that it stored on a cassette tape. After capturing the image, it would take the machine 23 seconds for the image to be recorded to the tape. In order for it to be played back, it had to be read by a specially designed Motorola microcomputer and displayed on a television screen.

It wasn’t much, but once Kodak’s management saw it in action, they did what any film company executive would do, and shelved it.

Although it would seem that a company like Kodak would have done anything in their power to prevent future development of the digital camera as it would have (and did) directly impact their film business, Kodak actually helped develop many of the world’s first digital cameras. Their partnership with companies like Nikon, Canon, and Fuji paved the way for the advanced digital cameras we use today.

The entire history of digital photography is vast and very fascinating. Perhaps some day I’ll write a feature article about it, but for now, this week’s Keppler’s Vault brings to you a bit of history about a technology that existed in between film and digital, called electronic still photography.

With a digital camera, electronic sensors arranged in a grid detect light and turn that light into a digital signal, which is written as a data file to some kind of storage device, usually flash memory. After the digital image is captured, a computer reads the data file and pieces the various 1s and 0s back into an image that can be displayed on a screen.

An electronic still camera also uses a digital sensor to capture an image, but it differs in that it doesn’t actually store it as a digital image file. After the sensor captures the image, it converts the electric signal to analog video and writes a single video frame to some type of magnetic media. Essentially, they’re like a camcorder, but instead of capturing video motion, they capture one single frame at a time.

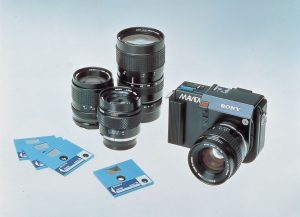

The most common example of an early still video camera was the Sony Mavica prototype from 1981. At the time, it was the world’s first filmless electronic still camera. The name Mavica is said to stand for MAgnetic VIdeo CAmera. The Mavica used a proprietary 2 inch “Mavipak” floppy disk format that Sony had developed for the camera.

The Sony Mavica was the first still video camera in the world and was presented in a familiar SLR style with it’s own unique interchangeable bayonet lens mount. Three lenses were available for it, a 50mm f/1.4, a 25mm f/2, and a 16-65mm f/1.4 zoom. The image to the left shows the Mavica with all three lenses (the 50mm f/1.4 is shown twice), and a couple of the 2″ Mavipak disks.

Images stored on the camera could only be displayed on a television or video monitor using a special purpose external disk drive. Each image had an approximate resolution of 570 x 490 which had it been a digital camera, would have been stated as 0.27 megapixels. Each Mavipak disk could hold up to 50 images on a single disk.

That original Sony Mavica was never sold to the public, but over the course of the next decade, a huge variety of electronic still video cameras were released by companies familiar in the photography industry like Canon and Kodak, but also by consumer electronics companies like Sony and Panasonic.

This week’s Keppler’s Vault brings you two articles, the first from the February 1986 issue of Modern Photography and has the pretty descriptive title of “What’s Really Going On In Electronic Still Photography?” Authored by Herbert Keppler, this article isn’t much of a review of any electronic still cameras, but more a review of the state of the technology at the time.

The article starts off much as I would predict a 1986 article about electronic cameras would, suggesting that readers of the magazine have been cautiously watching this new technology with “ever growing concern”. Would their prized Nikons and Hasselblads soon be obsolete, ready to be thrown in a junk pile, replaced by an army of filmless cameras with quality that puts film to shame?

The concerns of an electronic camera revolution were valid, as by 1986, electronic video cameras had well entrenched themselves as capable replacements to 8 and 16mm cinema film formats, so why couldn’t something happen with still film photography too?

Putting his reader’s immediate fears to rest, Herbert Keppler, as he often did, gazed into his crystal ball and made some predictions that now with the benefit of hindsight turned out to be surprisingly accurate.

Here are some of Keppler’s quotes, followed by my take on what actually happened.

…some new electronic techniques are going to be applied to regular silver-halide emulsion imaging that will give you image quality with present cameras far superior to what you have now.

It probably wasn’t a stretch in 1986 for photographers to see how computers could be used to enhance existing images. With programs like Adobe Photoshop and Lightroom, we can now modify images in post processing to enhance sharpness, contrast, shadow detail, and color shifts in ways never before possible.

The images made are primarily designed to be shown on TV which may not be the place where you want them…photographers want prints, and if they’re slide film users, they want to project pictures on a large screen where all the detail can be seen.

This one is both a hit and a miss in that Keppler was correct that photographers didn’t want to see their images on a screen, but that was only true when using 1986 television and electric camera technology. Back then, images from an electronic camera shown on a screen had significantly less detail than a print would have.

Today, with advances in modern digital cameras, high definition televisions, and smartphones with pixel densities over 500 PPI, the vast majority of images taken today are viewed on a screen. I have no stats to prove this, but I would be willing to bet that less than 1% of all images taken on a smartphone or traditional digital camera are ever printed.

The electronic camera today simply cannot record enough information to provide pictures with sufficient detail. Additionally, there is a growing number of technicians who feel that the quality characteristics of an electronic image may never match that possible from silver-halide material.

Keppler was correct that in 1986 electronic cameras had nowhere near the ability to produce images that matched that of competing film formats. Of course this would change in the decades after this article, but his prediction that some people would never feel that the quality characteristics would never match that of film is an argument that people still have today in 2021.

There is no debate that modern digital cameras can out resolve film, but that’s not what he’s saying. Keppler said “quality characteristics” which I interpret to mean the “look of film” that digital photographers today are still trying to recreate with plugins and filters, and is one of the reasons people like me keep shooting film.

Electronic information is generally discussed in terms of number of pixels captured.

While it’s not appropriate to credit Keppler with the idea that an electronic image is made up of pixels, his simplification of how pixels relate to electronic (and later digital) photography is another example of how forward thinking he was.

…we would need a still electronic imaging system offering between 4 million and 6 million pixels for a useable electronic still camera system with sufficient detail in the images to make good professional prints…such a system rivaling 35mm might not be available until way past the year 2000.

Herbert Keppler credits Dr. L.J. Thomas from Kodak for this one, and of all the predictions in this article, this one is amazingly accurate. Using my own personal observations, I found that once digital cameras reached the 5 to 6 megapixel barrier, that is when digital images started to match and surpass the quality of 35mm film. Some people might argue that you need as many as 10 megapixels or more to match film, but when I look back at images I took with my 5 megapixel Canon PowerShot S2 IS I mentioned earlier in this article, they look pretty dang good!

The second part about his prediction of ‘way past 2000’ was correct too. Nikon’s D1 released in June 1999 had a 2.7 megapixel sensor, and the D1X update from February 2001 bumped it to 5.3 megapixels. While February 2001 is hardly “way past 2000”, the Nikon D1X had a list price of $5350 in 2001, which when adjusted for inflation compares to nearly $7900 today, making it well out of reach for most people. Affordable 5 megapixel cameras would take another 3-4 years to be released.

Since electronic images can’t be compared directly with film in terms of graininess, pixels are used instead. Film pixel counts are equivalents.

Keppler touches on the debate of film versus digital which has existed for the past 20 or so years about how many pixels are required to reach a comparable quality of film. The problem with doing an A/B comparison between the two mediums is that there are far too many variables to consider as the type of film makes a difference as does your ability to “resolve” it. Scanning the same 35mm negative using a flatbed scanner versus a Noritsu dedicated film scanner versus a Heidelberg Tango drum scanner are all going to produce different results. Simply taking a photograph of something using both a 10 megapixel digital camera and a Nikon F3, and scanning it’s negative using an Epson V600 is not a fair comparison.

So while Keppler was correct that coming up with an accurate equivalent is difficult, he does it anyway, and lists several equivalent resolutions for several kinds of film. Numbers ranging from 1.5 megapixels for Kodak Disc film to a highly ambitious 18 megapixels for Kodacolor VR100 film are listed. To his credit though, I doubt anyone in 1986 had access to anything that could scan at anywhere near an 18 megapixel resolution, so his numbers are likely just optimistic estimates.

…enhancement could turn the (Kodak Disc film) format from a moderately successful system into a rip roaring success…

Uuuh…no. This did not happen! Shame on you, Bert! 🙂

The rest of the article talks about film enhancement techniques developed by Kodak involving magnetic tape, high resolution printers, and things like “convolvers” and “spatial frequency domains” that while not relevant today, are glimpses into early versions of digital post processing that likely formed the foundations of tools found in Adobe and other software suites that we use today.

As an added bonus, I found another article from the December 1981 issue of Popular Science that previews the Sony Mavica and the promise of a filmless camera revolution.

All scans used with permission by Marc Bergman, 2021.