There have been many firsts in the history of photography. First photographic process, first use of film, first box camera, first SLR, first digital camera, etc.

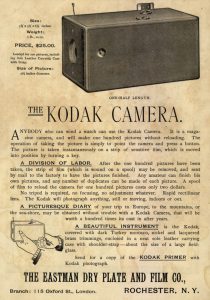

Of all those firsts, in 1888, a new camera made it’s debut that was the first of it’s kind, first to use a new type of roll film, first affordable camera for the novice, and first to be released by what would later become the largest photographic company of the 20th Century.

That camera, of course, is the 1888 Kodak Camera.

A quick bit of history is that on July 12, 1854, in Waterville, New York, a man named George Eastman was born. Eastman was forced at the age of 15 to drop out of school and work to help support his mother and older sister after the death of his father and another sister in 1862 and 1870 respectively.

George Eastman didn’t initially have an interest in photography as a child, and it wasn’t until the age of 23 that he had found a passion for it, working as a part time amateur photographer to supplement his day time banker’s income.

As did most photographers of the day, Eastman used a wet-plate process, but found the weight of equipment and steps necessary to develop images to be cumbersome and sought to find an easier method for making photographs. After reading about a dry plate process in the British Journal of Photography, he decided to experiment on his own to develop his own dry plates in his mother’s kitchen.

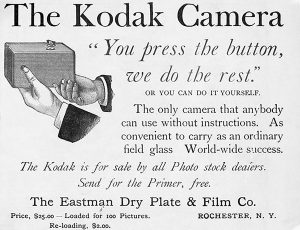

Within three years after picking up his first camera, Eastman was successfully producing his own dry plates and selling them locally to other photographers. This led to a full time interest in photography and a continued passion for simplification of the photographic process, a hallmark of what would later lead to developments of the Eastman’s first roll film in 1885, the first Kodak camera in 1888, the first transparent base film in 1889, first pocket folding Kodak in 1898, the first Brownie box camera in 1900, and continued innovations throughout the 20th century.

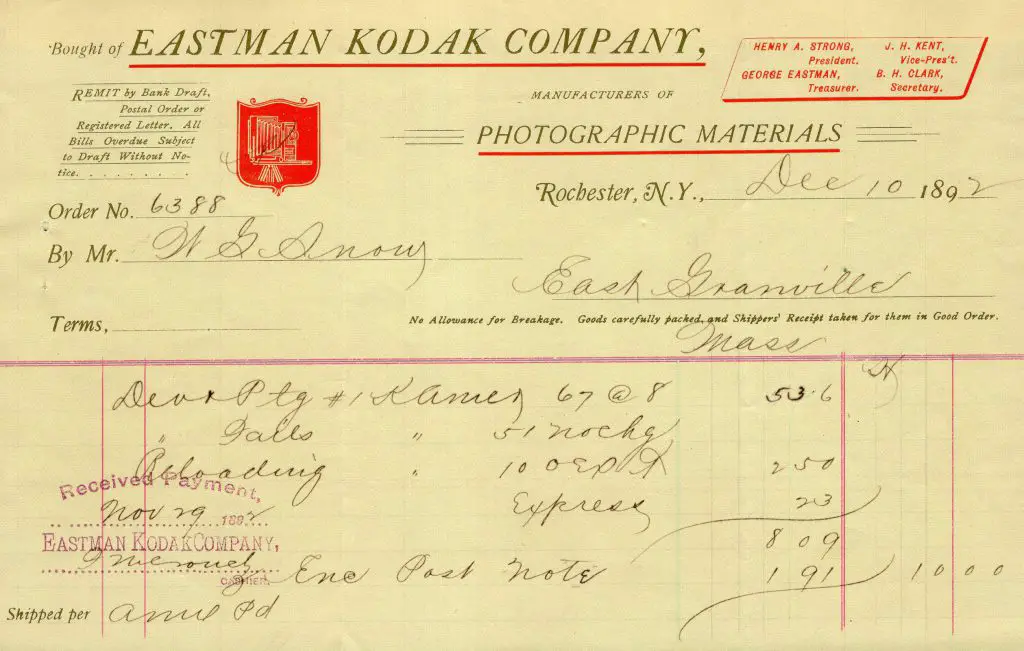

When it was first released in 1888, the Kodak sold for $25 and it came pre-loaded with a single roll of photographic negative paper that was capable of making 100 exposures. When adjusted for inflation, this price compares to about $690 today which isn’t exactly cheap, but considering the alterative would be to buy a whole studio worth of equipment, it was a bargain. Although many articles online suggest the Kodak was loaded with film, this is not true, at least not in the modern sense of what we call film today as celluloid film would not be commercially available until 1889. The “film” loaded in the Kodak was a negative paper backed film that when sent back to Eastman, would be developed and contact printed onto photographic positive paper. Inside the camera was a circular mask that would produce the Kodak’s distinct circle images.

When you were finished shooting all 100 exposures, you would send the camera back to Kodak along with $10 and they would have your film developed and printed. The camera would then be reloaded with a fresh roll and sent back to you. For the photographer familiar with developing, Kodak provided instructions to do this yourself if you so chose.

Although not exactly cheap, it was still a far cry from the cost involved with a professional studio camera, lens, and equipment. Not to mention the need to create and develop your own plates was out of reach of the novice photographer. The Kodak simplified photography enough to where anyone could do it making it the first consumer point and shoot camera.

This week’s Keppler’s Vault comes from the November 1980 issue of Modern Photography and features Jason Schneider’s Camera Collector column. Jason’s column was a regular fixture in that magazine for over 20 years and took a look at countless different cameras from the 19th and 20th centuries. His insights into each model’s history and how they were used have helped me in writing many of my own reviews, and although each of his columns is usually pretty short, they are consistently a treasure trove of useful information.

Jason’s November 1980 column was devoted entirely to the original Kodak camera in celebration of the Kodak company’s 100th anniversary. He starts it off by saying this one was written in the style of a full Modern Test article, as if the magazine had been in existence at the time of the camera’s creation. It is not likely I’ll ever get a chance to test one of these cameras myself so Jason’s article is probably the closest I’ll ever come. In the spirit of Jason’s attempt to give the camera a regular review, I thought I would do the same thing.

The Kodak (1888)

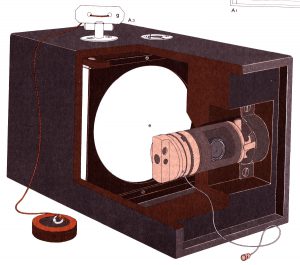

This is the Kodak Camera, a simple box camera made by the Eastman Dry Plate Company of Rochester, NY in 1888. The Kodak was Eastman’s first attempt at making a photographic camera and came preloaded with a roll of 70mm wide photographic paper backed film that was good for 100 exposures. When the roll was fully shot, the camera was to be returned to Eastman, to have the film removed, developed, contact printed and mounted to cards, the camera reloaded with a new roll, and it sent back to you. For the photographer brave enough to handle the developing him or herself, Eastman would sell rolls of film separately, allowing the user to remove, develop, and reload the film themselves. The Kodak was a pioneering advancement in photography, not only because of the camera’s simple design, but also the use of photographic roll film, and being the first ever Kodak Camera.

Film Type: 70mm roll photographic negative paper (100 2 5/8″ circular exposures per roll)

Lens: 2 1/4″ (~57mm) US 4 (~f/8) Rapid Rectilinear uncoated 4-elements in 2-groups

Focus: Fixed focus ~4 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: None, Image estimated using 60 degree lines on the top of the camera

Shutter: Spring Tensioned Rotating Barrel

Speeds: Single Speed ~1/45 second

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Weight: 1 lb, 10 oz. with film (~737 grams)

Manual: https://www.pacificrimcamera.com/rl/00104/00104.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Kodak camera is an easy to use and foolproof all in one solution for the amateur who wants to be free from the burden of understanding how photography works. As Eastman says, “you press the button, we do the rest”, the Kodak really is as easy as that. With a limited ability for exposure, the camera requires good lighting for properly exposed images, but with a near focus free operation, the camera can easily handle nearly any photographic situation, assuming the lighting is right. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 50% | |

| Bonus | +2 for extreme historical significance, the first ever Kodak camera, first point and shoot camera, and one that started an industry | ||||||

| Final Score | 14.0 | ||||||

The Kodak is a wooden box covered in Moroccan leather measuring 6 1/2″ in length by 3 1/4″ wide by 3 3/4″ tall. The camera weighs 1 pound and 10 ounces loaded with film and feels sturdy and well made, with a box built by a Rochester cabinet maker. George Eastman created this camera as a way of simplifying the process of photography to make it accessible by anyone.

In it’s marketing, Eastman cleverly promotes it’s simplicity by saying “You press the button, we do the rest”, and if there was a more appropriate slogan for a new product, I haven’t seen it.

The camera’s controls are easy to understand and logically laid out. A string on the top of the camera is connected to an internal ratcheting system that winds up the shutter for a total of 4-6 exposures before having to wind it up again. The camera lacks any sort of double image prevention, so you must remember to advance the film using the key on the back of the top plate in between each exposure or else you risk double exposing the same image.

With the shutter set and the film advanced, firing the single speed shutter is a matter of pressing the small button on the camera’s left side. It’s location is within easy reach of the photographer’s left hand while supporting the camera from the bottom.

Although the Kodak’s shutter is only capable of a single speed, long exposures may be accomplished by intentionally running down the clockwork spring tensioned by pulling the spring and manually rotating the lens barrel into an open position with your finger and leaving the lens open for as long as the exposure requires. Ending the exposure is accomplished by either covering the lens with a lens cap, or pulling the spring to tension it again.

Inside the camera is a round mask that produces the Kodak’s distinct round images. The decision to make round images was not purely for aesthetics, but the use of what at the time would have been considered a wide angle ~57mm lens, the Rapid Rectilinear design would have produced extremely soft corners, so by creating a round mask, these undesirable parts of the image were eliminated, only allowing the sharpest parts of the image to be recorded.

The film inside of the camera was 70mm wide photographic paper which Eastman sold separately for those wanting to reload the camera themselves. Optionally, the entire camera could be sent to Eastman and they would unload, develop, and reload the film for you. If you so chose to handle film loading yourself, the camera could be opened by unscrewing the film advance key on top of the camera and gently sliding the film compartment out of the back of the camera.

The photographic paper roller system was quite unique. A total of 5 wooden spools handled the paper transport which was geared in a manner that the paper could only be advanced in one direction, but also by preventing backwards transport meant that tension could be maintained throughout the entire roll, helping with paper flatness. A clever feature of the paper transport is that as the paper transported through the camera, two sharp notches would notch the paper at the top and bottom, in between each exposure, making it easier to tear the paper safely without cutting an already exposed image in half. This allowed for unloading of a partially exposed roll for development. While most users would simply wait until the entire 100 exposure roll was shot, if you so chose, you could tear out as little as a single exposure for developing if you wanted.

George Eastman’s Kodak camera was well thought out, and found a near perfect balance of innovative features packaged together in a wooden box that would accomplish it’s mission of making photography accessible to anyone who wanted it. The 4-element semi wide angle Rapid Rectilinear lens produced images of sufficient quality and allowed for focus free options of subjects from four feet to infinity, plus the speed of the shutter allowed for hand held shots with a minimum of motion blur.

In Schneider’s article, they observed two nitpicks to the camera’s design, the first was that it was lacking in any sort of tripod bushing, which meant that any method of stabilizing the camera for interior shots required setting the camera down on a flat surface such as a table. Had a tripod bushing been included, this would have allowed for greater stabilizing in locations where a flat surface was not available.

The second nitpick was that if exposed to direct sunlight, the rotating shutter barrel on the front of the camera lacked enough light sealing properties to completely keep light out. In use, images would be fogged or exhibit signs of light leaks if direct sunlight hit the front of the camera. Some kind of capping device that protected the barrel when not in use could have prevented this.

As a whole, the Kodak was a rousing success, not only introducing novices to the wonders of photography, but also helping to establish George Eastman’s company at the forefront of the photographic industry. In fact, success of the Kodak was so great, that in 1892, the Eastman Dry Plate Company would be renamed as the Eastman Kodak Company, a name it would retain for decades to come.

The original Kodak was only produced for about a year after which an estimated 5200 cameras were made. In 1889, a new camera that looked very similar called the No.1 Kodak replaced the expensive to manufacture barrel shutter with a simpler sector shutter. It used the same 100 exposure roll of 70mm film and had most of the same features, but had a few cosmetic differences including a relocated shutter release, differences in where screws are located, and that the glass lens is always visible. Shortly after the No.1 Kodak was released, a variety of other cameras sharing the same basic feature set, but shooting larger images were released as the Nos.2, 3, and 4 Kodak. All four models would be produced concurrently and all would be discontinued in 1897.

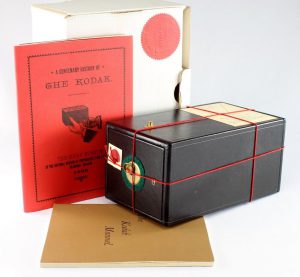

In 1988, to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the original Kodak, the Eastman Kodak Corporation would create a limited edition replica of the original Kodak. The camera was non functional, but came wrapped in genuine leather, and with a reproduction manual and some literature.

In the years after the 1888 Kodak was produced, the company that would eventually become Eastman Kodak pioneered many advancements both in Kodak film and Kodak cameras. In the 20th century, Kodak would release at least 30 different film formats, and several hundreds of different camera models.

George Eastman’s contributions extended well beyond his company, as he was a prolific philanthropist who funded schools, charities, and hospitals. His legacy would live on via the George Eastman Museum, which today still houses many of Kodak’s most pioneering and significant designs.

All scans used with permission by Marc Bergman, 2021.

Film was actually developed by an Episcopal priest by the name of The Rev. Hannibal Goodwin. While Fr. Goodwin filed for a patent in 1887 it was not granted until the fall of 1898. He died in 1900 before he could capitalize on his invention. His widow sold the rights to what would become ANSCO. They sued Kodak for patent infringement and were awarded $5,000,000 (about 140 million today) in 1911. George Eastman perfected a way of mass producing film although there is some indication that idea was actually that of an employee.

Hi! Just discovered your Keppler’s Vault series. I too have fond memories of Herbert Keppler. I’m most interested in Modern Photography from about 1965 to its end in 1987. I’m fascinated by the mix of mechanics and electronics of this era. Keppler was my go-to read in Modern Photography and then Popular Photography for 25 years. Jason Schneider was a strong #2. He could be pretty funny, although he used a formal 19th century tone in this Kodak article. I’ve scanned (for my personal interest) a couple hundred MODERN Tests, plus another hundred feature articles. However, I don’t dare post them, because MODERN’s copyrights are likely owned by Disney, and you know how aggressive Disney is about protecting their property.

I posted a history of safety film on POP’s online forums – before the forum was ended. It’s gone now. Yeah, Eastman tended to take credit for any invention made by anyone working for him. Kodak Labs was one of the first megacorporation research labs. Godowsky and Mannes are remembered for Kodachrome, because they started their work before they joined Kodak. Eastman was also willing to steal from others at the beginning, before he got into trouble. Intellectual property was not well protected in the 19th century and the Kodak-Goodwin/Ansco case was a landmark in 20th property rights.

Paul, thanks for the comment! I am happy that you’ve been able to start going through my Keppler’s Vault series. A large number of them are from those years of 65 to 87 that you remember, but I have many more that go back farther. I have one even from the 30s, way before Keppler started working for Modern. I wish I had a chance to meet, or even just talk to him before he passed away, but as is the case with everyone, people get older and I feel as though by me sharing this stuff online, it keeps those people’s memories (and work) alive!