Lens coatings are good. If a single coating is good, then multiple coatings must be better.

This concludes the extent of my knowledge about lens coatings. I suspect I am not alone as a good number of digital and film photographers and collectors probably have about the same understanding as I about those mysterious bluish purpley green, sometimes yellow and orange, possibly radioactive reflections we see inside of our beloved pieces of glass.

In the years after World War II, lens coatings became more and more common. Usually associated with color photography, various methods developed by American, German, and Japanese companies to coat their lenses also helped to reduce flare, haze, and even make the lenses more resistant to scratches.

This week’s Keppler’s Vault brings you two articles about lens coatings, the first from March 1960 and the second about multi-coated lenses from June 1975. A bonus third article is a short one from December 1958 which discusses the use of radioactive glass in lens making which was another method employed to help improve contrast in mid century lenses.

The first article starts off similar to what I said above in that photographers take lens coatings for granted, knowing that we like them, but maybe don’t quite understand how they do what they do.

If you are like me and have a rudimentary understanding of lens coatings, the first two pages of the first article are definitely worth checking out. Things start to get technical by the end of the second page, but a simple primer of why an uncoated 4-element Tessar lacks contrast is explained in very simple terms. A little more history of how the earliest lens coatings occurred naturally is fascinating to think that in the 1800s, the more you used a lens, the better it got is cool to think about as well.

The rest of the first article discusses how lenses are coated and the challenges involved in making perfect corrections across the visible spectrum of light. Red, blue, and green light have different wavelengths that react differently when passing through or reflecting off glass elements. The lens coatings from the era in which this article was written were not able to perfectly correct these differences, but still, the improvements from uncoated lenses are still worth it.

At the very end of the article is a section called “To coat or not to coat” wherein the question is asked if it’s worth it to have previously uncoated lenses sent in to be coated. This is pretty amazing to me to think that there was a time when photographers would consider sending in their pre-war Elmars and Biotars to have them coated. I am unsure how big of a market this was, but I have to imagine at least a decent number of photographers had this done.

The second article fast forwards a decade and a half to 1975 to a time when a single lens coating wasn’t enough and lenses were receiving “multi-coatings”. As I pondered at the start of this article, more is better, right?

With the release of the Asahi Takumar SMC 50mm f/1.4 lens in 1972, which was first multi-coated SLR lens, multi-coating became THE buzzword in the photographic community. The idea that a single lens coating has limits, that adding more layers could improve was probably an easy sell to someone looking to upgrade. Multi-coated lenses promised further reductions in flare with improved contrast, and better light transmission making images shot with these lenses even better.

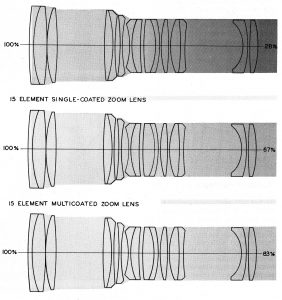

Modern’s article has quite a number of test images shot with uncoated, single coated, and multi-coated lenses, showing off how things like ghosts and flare are controlled with each. On the fifth page, they show how lens coatings affect light transmission. As light passes through each glass element of a lens, some of the light is lost. In a 5-element uncoated lens, only 63% of the light that entered the lens, exits it. With the same lens single coated, the transmission rate improves to 84%, and with multi-coating, improves further to 91%.

The more elements in a lens, the greater improvement there is. Using a zoom lens with 15-elements, the transmission rate from an uncoated to multi-coated lens jumps from an abysmal 28% to 83% proving how valuable lens coatings were in the widespread use of zooms.

As was the case with the 1960 article above, the 1975 article continues to preach the benefits of coated vs uncoated lenses, but suggests that although multi-coating is better than single coating, in real world use, it’s less noticeable. The examples of flare in badly overexposed and slightly underexposed images show significant improvements from uncoated to single coated, but not so much to multi.

I don’t want to steal too much of the thunder from the article as I definitely think it’s worth reading from start to finish, but the article does an excellent job of walking that line of offering technical information about lens coatings, without losing the interest of the casual reader. Although the earlier article offers a bit more history and a great explanation of why lens coatings are needed, this second article shows a lot more examples to further prove the point.

Finally, I found a short bonus article from December 1958 that’s not specifically about lens coatings, but talks about the widespread use of rare-earth lenses from the era that were found to help improve light transmission similarly to lens coatings. As collectors know today, many lenses from the mid 20th century used glass that contained thorium or lanthanum that is slightly radioactive, some of which can be detected with simple consumer grade Geiger Counters. I’ve heard of stories of collectors getting packages containing these lenses rejected by the postal service for excessive radiation.

Many of the best pre-war lenses were made of something called “Schott glass” which is named after Otto Schott, who in 1881 began research into ways of adding these materials to glass in an effort to improve their performance.

Today, the thought of a radioactive camera lens sounds scary and to many, brings back flashbacks of Chernobyl and Three Mile Island, when in reality, the amount of radiation contained in these lenses is far below trace amounts that we encounter every day in our normal lives.

There’s a bit of history here about how rare-earth lenses became common and how the technology was advanced throughout the years.

All scans used with permission by Marc Bergman, 2021.

hi Mike! for those too lazy to read the whole articles, here’s my 30- second version

http://rick_oleson.tripod.com/index-166.html

:)=

Thanks for the link Rick! It’s always good to have shorter explanations for things too! 🙂

Great article and great finds!

I would just like to offer some corrections. Minolta was the first company in the world to produce multicoated camera lenses, with the first being the 3.5cm F3.5 from 1956 for the Minolta 35 rangefinder, although it is very rare to find one and I couldn’t find a good image, but here is the same lens in Super A from 1957-58. Minolta literature from 1958 states that the 5cm F1.8 in LTM has the Achromatic Coating too although most/all seem to be predominantly golden with some violet. The 5cm F1.8 in Super A from the same year is nearly always seen in green, so perhaps there were some differences or practical reasons for this. On the LTM version it is, I would say, quite similar to the coating on Canon’s restyled 50/1.8 LTM (black focus ring) of 1956, which is a departure from their earlier lenses that have a blue/blue-purple coatings.

That makes the first multi-coated SLR lens also from Minolta in 1958, but it seems to be almost exclusively used on the standard kit lenses like the 55/1.8. You will see some 55/F2 versions that have the green coating and others that do not. Another culprit is the 100mm F2. Technically there is a 1-5 year difference between the above lenses but you can find examples of the 1966 ‘MC’ in both types of coating. My theory was that they are both multi-coated, just that there may be material shortages in the coating material for optimum/design performance or it is the result of the continuous adjustment in the production to account for changes in the refractive index or purity of materials, since the coating should be matched to the refractive-index as best as possible. It could also be the result of uncontrollable variations in the layer thickness due to limitations of the accuracy of the existing vacuum chambers.

Pentax released Super-Multi-Coated Takumar in 1971, but it’s at least, visibly, less advanced than the SMC lenses that came several years later. The first S-M-C coating, like Minolta’s, did not apply equally (by simple visual inspection) to all surfaces or all lenses.

The general consensus is that Pentax purchased/licensed their coating technology from OCLI which was perhaps the world pioneer in optical coatings research and computer-controlled coating production processors. There is brief article about that here and the reading about OCLI is interesting in itself. art. 1 ; art. 2 ; art. 3. Actually, last I checked, Ricoh/Pentax does not provide any additional information on the company history pages. [Here is a nice side by side showing the difference against the earlier Super-Takumar) (https://3.img-dpreview.com/files/p/TS560x560~forums/58145079/6eca36be6e494e05aed7a332640fab46). It doesn’t appear that the Super-Takumar coating was any less advanced than the earlier Minolta and Canon coatings that were not always green but on the cusp of ‘achromatic coating’ as described in the 1960 Modern Photography article. To my eyes the Super-Takumar coating could even be described as slightly green, sometimes, a good sign that there is something more complex than the basic blue or amber coatings common throughout the late 40’s and 1950’s.

Even Fujifilm states they have used EBC first in 1972 however separately they state that it was first applied in 1969 on television zoom lenses. Does that make it feasible that it was still a private and experimentally applied technology for the 1964 Olympics, as stated in the ‘AOHC.it’ article? I think that could be reasonable, as if it were in a less-advanced state not yet ready for commercialisation.

It’s an interesting thing to explore although I suppose the real truths are probably deep in some Japanese archives, not that it matters much at all. In my experience it’s the physical design of the lens, the size of the front element, the number of flat element surfaces, and the quality of internal finishing which really determines the performance differences when it comes to flare and ghosting. All lenses with some form of two-material coating are going to give very high transmission where it’s wanted. Supposedly the purpose of Minolta’s coating research was to colour-correct their entire lens range to have a consistent colour reproduction/saturation, however the evidence for this is somewhat anecdotal at best and not obvious in practice. It’s an idea that would really need to be tested on a spectrometer with carefully selected lenses that are within the same production period. There tends to be some truth to these things, but there also a lot of marketing fluff!

Rather surprisingly, Zeiss states they were researching 2 and 3-layer coatings already in WW2 and stated these were applied to some wide-angle lenses in the 1950-60’s that I could not find further support for. It appears that the MC Jena Pancolar 50/1.8 appeared in 1969 with multicoating but that may be wrong. Zeiss states the first multi-coated T* and MC Jena DDR lenses appeared in 1972 for Photokina.

Today, 6-10 layer ‘broad-band’ AR-coatings appear to be available on even the cheapest Chinese optical products, but it doesn’t mean they have been carefully designed and applied to match the refractive index of each glass substrate (and each subsequent coating layer) – it’s highly unlikely given the cost of these products. Coatings applied in a one-size-fits-all manner simply aren’t as efficient or effective as the custom coatings that might be on a lens from manufacturers like Zeiss, Pentax or Sigma. In general, however, they do seem to achieve broadly good colour balance and generally higher transmission than what vintage lenses from the 60s-80s will offer – potentially excluding the later Zeiss T*, Fuji EBC and Pentax SMC.

Fascinating articles! To think that ‘Modern Photography’ could afford to custom-order three identical lenses but with different coatings, as well as a spectrophotometer, while DPReview today can’t review the latest piece of gear if the manufacturer doesn’t ship them a copy… oh, how the mighty have fallen.

This is the first of this series that I’ve read (good stuff – I will be reading more). What I don’t understand here is that none of the referenced articles are by Herbert Keppler. I had guessed that Keppler’s Vault referred to his work. Eh?

This series of articles is named in honor of Herbert Keppler. As you probably know, Herb was one of the most well regarded authors and editors in the entire film industry through his several decades of work writing for both Modern and Popular Photography. Although many of the articles in this series were written by him, not all were. I took some liberty by including stuff from the same era and from the same magazines that he did work for, that I found to be interesting and worth being revisited today. Think of this sort of like how they name libraries in honor of special people. Perhaps a better name for this series would have been the Keppler Memorial Library! 🙂

Keep reading. Currently there are 101 articles in this series, all of which have fascinating information from a wide variety of topics that I think is worth a read. If you like Zeiss information, also check out the Zeiss Historica section on this site where I’ve published every single issue of the Zeiss Historica Newsletter from the very first issue in 1979 to the last in 2016. There’s information in there you cannot find anywhere else online.

Ah – I see… it was obviously a noobie question but now I’m up to speed.

This is great stuff and I look forward to reading more. Oh, and thanks for the mention of the Zeiss Historica section – I am recently an interested party due to procuring a Zeiss Ikon Ikonta 521/2 (6X9 images!).