This is a Zenit-E 35mm SLR camera, made by Krasnogorski Mekhanicheskii Zavod (KMZ) in the former Soviet Union between the years of 1965 and 1986. The entire Zenit (Зенит) line was extremely successful and not only sold very well, but it has become an iconic camera of the Soviet Union. Millions were made and sold domestically and exported all over the world. Versions of this camera were sold in countries like the United States, Australia, and Germany under a variety of names like Kalimar, Cosmorex, and Revueflex. The Zenit-E was a very long lived model with a simple shutter and a match needle selenium exposure meter.

This is a Zenit-E 35mm SLR camera, made by Krasnogorski Mekhanicheskii Zavod (KMZ) in the former Soviet Union between the years of 1965 and 1986. The entire Zenit (Зенит) line was extremely successful and not only sold very well, but it has become an iconic camera of the Soviet Union. Millions were made and sold domestically and exported all over the world. Versions of this camera were sold in countries like the United States, Australia, and Germany under a variety of names like Kalimar, Cosmorex, and Revueflex. The Zenit-E was a very long lived model with a simple shutter and a match needle selenium exposure meter.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 58mm f/2 Helios-44-2 coated 6-elements

Lens Mount: M42 Screw Mount

Focus: .55 Meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Fixed SLR Pentaprism

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1/30 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: Coupled Selenium Cell w/ top plate match needle

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Coldshoe and M / X Flash Sync

Weight: 698 grams (body only) / 920 grams (w/ lens)

Manual: https://www.butkus.org/chinon/russian/zenith-e/zenith-e.pdf

Manual (alt version): https://mikeeckman.com/media/ZenithManual.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Zenit-E is one of the longest lived single camera model ever built and one of the most iconic of the whole Soviet camera industry. It is a simple camera with a large and squared “brick-like” body without many bells and whistles. It’s shutter has only 5 speeds, and the viewfinder has absolutely no information in it, not even a focus aide. Yet, despite its simplicity, therein lies it’s charm. This is a camera stripped down to just the bare essentials needed to capture a photo. Mount it with any number of Soviet, Japanese, or German M42 lenses and you can take some really great photographs with it. If you’re looking for a fully mechanical camera that offers little in the way of modern conveniences, this is a really cool camera to have. The fact that millions were made, make them really easy and inexpensive to add to your collection. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 20% | |

| Bonus | +1 for historical significance, one of the longest lived and popular cameras ever made | ||||||

| Final Score | 9.4 | ||||||

History

Growing up as a kid in the United States in the 80s, my knowledge of what life must have been like in the Soviet Union was heavily based off what I saw on television and the movies. WarGames, Red Dawn, Rocky IV, Red Heat, and the Hunt for Red October all taught me that the Russians were tough, no nonsense guys who wanted nothing more than to “crush us Americans”. They had a strong military, an adept space program, and were good at hockey.

Growing up as a kid in the United States in the 80s, my knowledge of what life must have been like in the Soviet Union was heavily based off what I saw on television and the movies. WarGames, Red Dawn, Rocky IV, Red Heat, and the Hunt for Red October all taught me that the Russians were tough, no nonsense guys who wanted nothing more than to “crush us Americans”. They had a strong military, an adept space program, and were good at hockey.

As I grew older, and looked past the political posturing, I realized that for many people living in the Soviet Union, the everyday people weren’t much different than Americans. They went to school, got jobs, had families, made babies, and wanted to buy things like vodka, cars, and cameras.

Without getting into any kind of debate or discussion about the differences of communism vs capitalism, one thing that is glaringly different between the two countries was in the variety and availability of the things people could spend their money on. Things just needed to work, and once they worked, there wasn’t as much of an incentive to change or improve on the design.

Cars like the Lada “Kopeyka” and the Dacia 1300 ruled the roads in the Soviet Union largely unchanged for many decades. The Soyuz spacecraft first took flight with a manned crew in April 1967, and is still in use today shuttling Russians and Americans alike back and forth to the International Space Station. It would seem the Soviet Union took the old saying “Don’t fix what’s not broken” VERY seriously!

If the Lada and the Soyuz were iconic stalwarts of Soviet era design in their respective industries, the camera equivalent to those long lived products was the Zenit SLR.

Like the Germans and Japanese, in the early 1950s, designers at the KMZ factory in Moscow were aware that the Single Lens Reflex camera was the future of camera design. The days of the rangefinder would be limited, and future success meant that an SLR needed to be released. The only problem was that at this time, the Soviet Union didn’t have too many original designs to base a new SLR off, so they took an approach that Nippon Kogaku and Kodak AG did with the Nikon F and Retina Reflex and created an SLR camera based off an existing rangefinder body.

The first Zenit (translated to English means Zenith, or ‘peak’) was nothing more than a Zorki rangefinder with the rangefinder removed, and a mirror box shoved in there. Since the early Zorkis still bore a strong resemblance to the Leica II that they were based off, the original Zenit model from 1952 looks what a Barnack Leica would have looked like if it was turned into an SLR.

Both the Zenit and the Zorki had the same elongated oval body with round advance and rewind knobs, both were bottom loaders, and both even shared the same 39×1 interchangeable lens mount. Although it might seem logical to share the same lens mount between an SLR and rangefinder based off the same body, this turned out to be a really bad idea as the mirror box in the Zenit required the lens mount to be pushed farther forward than it would have been on the rangefinder Zorki. The “flange focal distance” is different between the Zenit and Zorki which means the lenses were not compatible because the focus would always be way off. Although you could physically swap lenses between the Zenit and Zorki, your images would never be in focus. This probably confused many photographers back then and perhaps realizing this was a bad idea, KMZ would eventually switch to the M42 “universal” screw mount that was specifically designed for SLRs.

Over the next decade, the Zenit sold moderately well. The original model was available until 1956, and a slightly updated version called the Zenit-S (the Cyrillic S looks like a Roman C, so this camera is often incorrectly called the Zenit-C) was released that added a flash synchronized (hence the “S”) shutter. By 1960, the design of the camera started to change. As SLRs took their place as the most popular style of 35mm camera for pros and semi-pros, KMZ started working on many variants of the Zenit.

A short lived model called the Crystall (Кристалл) was released in 1961 with a new body and a hinged rear film back, but was ultimately a failure, being replaced after one year by the Zenit 3M. Up until that point the Zenit 3M was the most successful Soviet SLR, staying in production for 7 years and selling nearly 800,000 copies.

Before the end of the 1960s, KMZ would experiment with a variety of new designs for the Zenit, first creating a leaf shutter version (Zenits 4, 5, and 6), and then an all new design using a bayonet mount (Zenit-7), but it was a model released in 1965 called the Zenit-E that would prove to strike the right balance of design, functionality, and popularity.

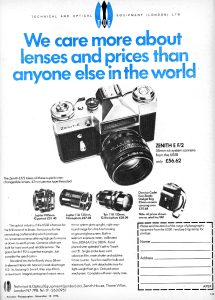

Featuring a large and boxy body with strong 90 degree corners and a prominent selenium exposure meter on the front face of the prism, the Zenit-E would first use the original M39 lens mount, but would quickly be changed to the M42 lens mount.

The Zenit-E would be produced until 1986 with only minor cosmetic changes to it’s design. In 1978, in anticipation of the 1980 Summer Olympics held in Moscow, many Soviet cameras like the Zenit-E received an “Olympic edition” with some variation of the Olympic rings and either “Moscow 80” or “Moskva 80” printed on it. Other than the logo, there is no difference between Olympic and non-Olympic editions.

Two variants, called the Zenit-EM and Zenit-ET would be released in 1972 and 1981 respectively, with an automatic diaphragm and redesigned cosmetics. Each of the new models were produced concurrently with the original models that came before them. The ET would be the last to be produced, when it finally ended production in 1991. Counting all three models together, total production of the Zenit E-series was over 7 million units.

The whole Zenit family saw many other variants that would take an entire article to fully cover. At one point in the early 1980s, the popularity of the Zenit line was so great, that the KMZ factory could not keep up, so the Belorussian factory BeLOMO started producing several of the most popular Zenit cameras to help keep up with demand.

In addition to sales in the Soviet Union, the Zenit was one of the most popular Soviet cameras for export. A dizzying number of export variants were created with names like Cosmorex, Kalimar, Prinzflex, Diramic, Global, and Revueflex were created for various Western markets.

Today, the entire Zenit family is known to most collectors, regardless of their interest in Soviet cameras. The Zenit-E, due in large part to the huge number that were made, are as “Soviet” as the Lada, the Soyuz, and Ivan Drago. They’re heavy, bulky, have limited shutter speeds, and don’t have a lot of bells and whistles, but the simplicity of the Zenit is perhaps it’s greatest asset as there’s little to go wrong. Contrary to many other kinds of Soviet cameras with questionable reliability, most Zenits can be found today in good working condition for very little money. For that reason, I think the Zenit-E is a no-brainer for any collector. It’s to Soviet Cameras as baseball and apple pie are to the United States!

My Thoughts

Twice now, I’ve hinted at a lineup of cameras that I admitted to having little interest in adding to my collection. The first were East German made Praktica SLRs. Stalwarts of post WWII Soviet controlled East Germany, the Praktica lineup of cameras were generally pretty basic, rudimentary bricks that offered little in the way of innovation or design. It wasn’t until a reader of this site from the UK named Paul Snaith contacted me and pointed out a lack of Prakticas in my list of reviews.

After a few email exchanges with Paul, he agreed to send me a Praktica IV F SLR that I would shoot and eventually review. As it would turn out, I ended up loving that Praktica quite a bit!

In an effort to take advantage of expensive international shipping rates, Paul discovered that if he could send one camera to me, he could easily fit another in the same box for nearly the same price. That second camera turned out to be another that was lacking on my site, a KMZ Zenit-E. In both cases, the cameras came to me body only, but I had period correct Zeiss Tessar and Helios 44-2 lenses that I could use on both bodies.

Of the two cameras, the Zenit was the one that took longer to grow on me, and as such got pushed farther down ‘in the queue’ before I would eventually load in some film for some shots. On a random summer day, I grabbed the Zenit, loaded in a roll of Fuji 200 and quickly shot the roll over a weekend.

As you might imagine, the Zenit is bulky, but strangely, not as heavy as you might think. It’s brick-like shape, with sharp 90 degree corners give the illusion of a camera that’s heavier than it really is. Without a lens, the body weighs just under 700 grams. Not insignificant, but certainly less than other large bodied SLRs of the 1960s. The Helios 44-2 lens that I had mounted to it contributed another 220 grams of weight, bringing the combo up to 920 grams. The Helios lens has an N00xxxxx serial number which suggests it was probably made in the late 1960s and likely used a lot more brass than later examples would have. There is a lot of information online that recites the same rumor where Soviet lenses that begin with zeroes were created for Communist VIPs, but I don’t believe that to be true. The only thing that I feel saying with any level of certainty is that this particular Helios lens is an earlier example and therefore a bit heavier.

One way in which the Zenit does live up to it’s reputation is in it’s simplicity. The Zenit-E has a simple 5-speed shutter with nothing under 1/30 or over 1/500. For the professional photographer who needs a wide spread of speeds, this likely would be a major limitation, but for the everyday snapshooter, most normal scenes can be captured with one of those five speeds. Using Sunny 16 and 100 through 400 speed films, you shouldn’t be limited one bit.

The top plate is where the film reminder dial, popup rewind knob, and “match needle” light meter readout is. Unlike most match needle cameras of the 1960s and 70s, the needle is not visible within the viewfinder, so you must lower the camera from your eye if you wish to measure exposure using the meter. To the right of the shutter speed selector is the rewind button and film advance lever with manual exposure counter and threaded shutter release. Again, it’s rudimentary, but works fine.

The bottom of the camera is completely bare, save for the words “Made in USSR” silkscreened onto the metal and the tripod socket. The tripod socket uses the modern size of 1/4″ instead of 3/8″ like you normally see on older Soviet cameras. This started to become common in the second half of the 1960s because Soviet companies wanted to make their cameras more appealing to other markets. Notice that although this lens is not original to this body, you can see “Made in USSR” on the bottom of the Helios lens.

Minimalism continues on the back of the camera, with only the large circular eyepiece and film advance lever visible.

Like most cameras of the era in which the Zenit-E was first created, the film door opens with a latch on the camera’s left side. Simply slide up on the latch and the right hinged rear door pops open. Loading film is an uneventful left to right process. The fixed take up spool has only one slit in it for catching the leader. The cloth curtains on this Zenit-E were in great shape, suggesting that with care, these cameras can stay functional for quite a while. Despite this particular Zenit being made in 1978, it still uses all fabric light seals, which unlike the foam ones used by everyone else in the 1970s have not degraded. I did not have to replace any light seals on this camera.

The viewfinder for the Zenit has absolutely no information about exposure or selected shutter speeds or aperture. There’s no focus aides of any kind. No split image rangefinder, no ground glass circle, no microprism dot, nothing. There’s not even a Fresnel pattern to improve brightness, its just one big swath of frosted ground glass. Amazingly, it still manages to be “sorta” bright. In well lit scenes, it’s easy enough to focus and compose your images, but things get quite dim indoors. One thing I found interesting was the general shape of the viewing screen has soft rounded edges, almost like looking at an old CRT television.

I mentioned in the history section above that earlier Zenits used a variation of the M39 screw mount from the original Zorki rangefinder that this camera was based on, but somewhere after the start of Zenit-E production, KMZ wisely switched to the M42 screw mount which means that literally any other Soviet, German, or Japanese M42 lens will work on these cameras. For this review, I could have used any number of Zeiss, Pentax, or Yashica lenses, but that somehow wouldn’t seem right. The Zenit-E does not support automatic diaphragms, so any lens, even if it has an automatic diaphragm, requires you to first stop down the lens to get an accurate meter reading. The Helios 44-2 lens used here is a ‘preset’ lens so it was a perfect match.

The more I handled the Zenit, the more I started to appreciate it’s quirks as benefits. The lack of modern electronics and advanced shutters meant that it still worked properly. The ancient cloth light seals were still in tact and doing their job, so I didn’t have any messy foam light seals to scrape off and replace. The primitive viewfinder forced me to really concentrate on my compositions and think about what I wanted to shoot before pressing the shutter release. Even the shape of the body began to grow on me. Where some cameras have swoops and curves that haven’t aged well, the squared off corners of the Zenit had a clean and timeless look to them that I appreciated. The Zenit was winning me over, but what kinds of images would it make?

My Results

This Zenit-E was generously donated to me by a reader of my site named Paul who contacted me after noticing a void of Prakticas on my site, Once we discussed which camera he would send, he snuck in this Zenit-E as a bonus camera. Upon it’s arrival, I was pleased that it was in good shape and seemed to work correctly, but it still left a bit to be desired in terms of handling and beauty.

Not wanting to disappoint one of my loyal readers, I felt I owed it to Paul to at least throw a roll of Fuji 200 in the film and see what it could do.

As seems to happen with many cameras, while shooting the Zenit, it started to grow on me. Sure, it was like a large metal cube pressed to my face, and the sound of the shutter firing was a cacophony of metal gears and levers slapping together instead of the confidence inspiring “snick” often associated with precision Japanese cameras. But it had charm. The experience was so raw, almost carnal, I felt like I was using a relic from a forgotten era that needed a bit of extra persuasion to use.

I knew what to expect from this Helios 44-2 as I’ve shot it adapted to digital and on the Petri Flex V that I reviewed in 2016, so I guess I figured the images would turn out nice, but I was still quite surprised to see them appear on my computer screen after scanning them in.

As you can see, the images were spectacular. Although the light meter on this camera responded to light, I did not use it, instead shooting everything Sunny 16. The “preset” Helios 44-2 lens takes a bit of getting used to as you have to manually stop it down by rotating the outer ring before firing every shot, but after a couple of exposures, I got used to it.

I didn’t make a lot of effort to get any type of “swirly bokeh” that Helios lenses are known for, but I did try some minimum focus shots and enjoyed the semi-macro close focus capabilities of the lens. The Helios is a 6-element lens that renders images with extreme sharpness in the center and just a hint of softness to the edges which I enjoyed quite a bit.

I really enjoy photography, and I love cameras of all shapes, sizes, and technologies. Film is not better or worse than digital, SLRs are not better or worse than rangefinders, 35mm is not better or worse than medium format, and a rudimentary camera is not better or worse than a top of the line model. The Zenit-E is a relic from a previous era and one whose feature set was far surpassed by the rest of the world in the later decades of it’s production.

Yet, the Zenit has something more modern models don’t, which is history. In the earliest days of photography, chemists performed “voodoo” with explosive and highly poisonous concoctions on glass and metal plates, freezing time and capturing light in ways that had never been done before. The first people who ever had their photos taken were probably mystified and looked at it as some form of magic. They were likely awed at the camera’s ability to capture a moment and preserve it. That’s what the Zenit does. It’s a simple device that serves one single purpose, and it is noteworthy not for what it can’t do, but what it can.

Although it took me a little longer to come around to this model than the Praktica that Paul sent me, but it was no less of a rewarding experience. I am glad to have been able to shoot it and share my experience with you, and if you were like me, and had dismissed these models, give them a chance. Maybe the Zenit voodoo will capture you too!

Additional Resources

http://www.sovietcams.com/index.php?-1057156339

http://camerapedia.wikia.com/wiki/Zenit-E

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Zenit_E

http://cameras.alfredklomp.com/zenite/

https://www.casualphotophile.com/2017/08/23/zenit-e-camera-review-seizing-the-means-of-photography/

https://www.35mmc.com/04/08/2018/fathers-old-zenit-e-johann-wahlmuller/

https://simonhawketts.co.uk/2016/03/26/zenit-e-35mm-slr-review/

https://kosmofoto.com/2012/11/zenit-e-russian-camera-review/

http://www.commiecameras.com/sov/35mmsinglelensreflexcameras/cameras/zenit/index.htm

https://www.lomography.com/magazine/187194-zenit-e-the-sturdy-metal-heart-of-russian-photography

https://photography-on-the.net/forum/showthread.php?t=1491800

http://ussrphoto.com/Wiki/default.asp?WikiCatID=69&ParentID=1&ContentID=636&Item=Zenit+E

Great article. My first SLR was a Zenith E, bought it in the mid 70’s, I still have the lovely Helios 44-2 and use it for film and digital photography. I also had the pleasure ! of driving a Lada around the Latvian countryside in 1993.

Excellent article as always Mike. Thanks for taking the time to do a review of this often overlooked piece of Russian camera history. I can’t believe you knew about Lada cars. They were quite popular over here in the UK in the 70s and early 80s as they were very cheap to buy and run, but you had to have no sense of cool and be completely shameless to own one if you were below the age of 30. 🙂 And yes, the focusing screens on the Zenit Es are exactly like old TV sets – I wondered why they looked so familiar.

And the photos just turned out great too. Those Helios presets are dynamite. Again many thanks for doing the review. Red Oktober has been very interesting – it’s a good job it’s not the McCarthy era or you would have been sitting in a jail cell right now for publishing this stuff !!!

Very well written. Enjoyed reading it!

I was in the UK many years ago – partly to photograph a friend’s wedding. My Pentax ES was stolen out of my rental car – luckily everything else-including the Rolleis- was in the trunk. At the time UK camera prices were 2x what they were in the US and I was short on shopping time. I bought a Zenit -everything was OK- but it was just too clunky to keep using when I got home. Still have it somewhere.

Growing up in the US in the 70s, the most important thing I learned was that all Russian women were very large, wore babushkas, enormous overcoats, and stockings rolled down around their ankles, and drove tractors.

That has turned out to be not entirely correct.

I love the look of this camera, couldnt care less if it doesnt measure up to some western standard of handsome. Some super shots, spectacular is right. Well done

My first camera was also a Zenit. I have a soft spot for them, but don’t really enjoy using them due to the weight.