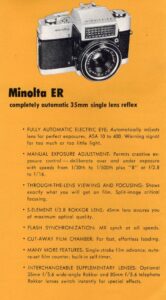

This is a Minolta-ER, a 35mm Single Lens Reflex camera produced by Chiyoda Kogaku Seiko K.K. in 1962. The Minolta-ER was a milestone camera as it was the first Minolta SLR with automatic exposure and was also the company’s first and only leaf shutter SLR. It offered shutter priority automatic exposure via the large selenium exposure meter located in front of the prism. The camera featured a fixed 45mm f/2.8 Rokkor lens, but was offered with two screw on accessory lenses which modified the focal length to either 35mm or 85mm, giving the camera somewhat of a full SLR experience.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 45mm f/2.8 Minolta Rokkor-TD coated 4-elements in 3-groups

Focus: 3 feet / 0.9 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Fixed SLR Pentaprism with Split Image Rangefinder and Ground Glass Collar, 0.7x Magnification

Shutter: Seikosha SLV Leaf

Speeds: B, 1/30 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: Coupled Selenium Cell w/ Shutter Priority AE

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Cold shoe and M and X Flash Sync

Other Features: Self-Timer

Weight: 866 grams

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/minolta_pdf/minolta_er.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Minolta-ER is a historically significant camera in the history of Minolta for a couple of reasons. Not only was it the only Minolta SLR with a leaf shutter, but it was also the first model with Shutter Priority AE. The camera itself is nicely built with a huge hump hiding the prism and meter. This causes issues seeing the settings around the lens, but in AE mode, you don’t really need it. The Rokkor lens delivers excellent results, as most Rokkor lenses do, but like most leaf shutter SLRs, these cameras can be very unreliable, so finding one in good operating condition will likely be difficult. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 20% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 9.8 | ||||||

History

The years between 1958 and 1963 were immensely exciting in the world of photography. In that five year period, we saw the rapid popularization of SLRs over rangefinder cameras, the release of first SLRs by Nikon, Minolta, Canon, Konica, Yashica, Mamiya, Petri, AGFA, and Voigtländer, many companies changed their names, Chiyoda Kogaku became Minolta, Kuribayashi became Petri, Yashima became Yashica and merged with Nicca, Riken became Ricoh, the rise of the auto exposure era, and the continued expansion of the Japanese photo industry.

The years between 1958 and 1963 were immensely exciting in the world of photography. In that five year period, we saw the rapid popularization of SLRs over rangefinder cameras, the release of first SLRs by Nikon, Minolta, Canon, Konica, Yashica, Mamiya, Petri, AGFA, and Voigtländer, many companies changed their names, Chiyoda Kogaku became Minolta, Kuribayashi became Petri, Yashima became Yashica and merged with Nicca, Riken became Ricoh, the rise of the auto exposure era, and the continued expansion of the Japanese photo industry.

In 1962, the Minolta-ER (which ER stands for “Electric Reflex”) would make it’s debut as the company’s first auto exposure camera and first leaf shutter SLR. That second fact is interesting as Minolta (still called Chiyoda Kogaku at that time) was not known for making leaf shutter SLRs. The design of most early auto exposure cameras had a mechanism that controlled the diaphragm, but required the user to manually choose an appropriate shutter speed. Thus shutter priority AE was the most common type of AE until the early 1970s when electronically controlled focal plane shutters became common.

While I have a general understanding of how both leaf and focal plane shutters work, how exactly they are controlled by a meter is still largely a mystery to me. That only leaf shutter cameras had auto exposure in the late 1950s and 1960s likely has to be due to a technical reason. It must have been easier to control the opening of a diaphragm coupled to a meter, than it would have been to control the speed of a shutter. Perhaps the infinite variability of the position of a diaphragm was more accurate than mechanical shutters which usually operated in steps. Whatever the reason, in 1962, shutter priority was king, and Chiyoda Kogaku entered the market with the ER.

The following article from the August 1962 issue of US Camera explores early auto exposure camera and what makes them “fully automatic”. It does a pretty good job of explaining how early AE systems work and somewhat confirms my theory that the use of leaf shutters and shutter priority was due to it being simpler. Although it makes no mention of focal plane shutters, it is plausible the same technology could be used in a shutter priority focal plane shutter camera, but definitely not aperture priority.

In 1958 when the first “electric eye” cameras as they were called then, entered the market, they were basic models like the Kodak Brownie Starmatic, Revere Eye-Matic EE 127, and the Bell & Howell Electric Eye 127. In the case of the Kodak and Bell & Howell models, they were glorified box cameras with single speed shutters and no focus aides. The Revere was slightly more advanced, offering a coupled rangefinder, but still a single speed leaf shutter.

Although technological marvels, these early AE cameras were largely ignored by most photographers. The idea that a camera could do a better job of determining exposure than a handheld meter was something that most pros had no interest in using. Also that the cameras themselves were quite basic further added to the ambivalence. By 1962, AE was gaining traction in the photographic world. More advanced cameras were starting to feature it, and the flexibility of multiple shutter speeds with TTL viewfinders added to the appeal.

Despite a number of firsts for a Minolta camera, the ER was not very successful and was not produced for very long. Versions of the Minolta-ER exist with the company’s name engraved on the top plate both as “Chiyoda Kogaku” and “Minolta Camera Co., Ltd.” suggesting the camera was produced at least until 1963 when the company’s name changed.

A huge amount of innovation in the SLR market during this time rendered the camera obsolete very quickly. Soon, CdS meters would replace selenium sells, TTL meters would replace body mounted ones, and auto exposure cameras with interchangeable lenses would quickly become the norm.

In my research for this review, I could not find any contemporary reviews, articles, or advertisements for the camera. The only references I can find from it’s release are short, to the point, list of specifications like in the image from a June 1962 round up of new models released at that year’s Photo Dealer’s Show.

The camera had a five speed Seikosha leaf shutter, flash synchronized at all speeds. It had a fixed pentaprism with bright Fresnel focusing screen and split image focus aides. It’s 45mm f/2.8 Rokkor-TD lens was fixed and could not be removed, although two accessory lenses could be purchased which screwed onto the front filter ring, altering the focal lengths to 35mm and 85mm.

At the time of it’s release, the price of “less than $120” probably means $119.50, which when adjusted for inflation compares to around $1175 today, making it expensive, but not out of reach for early adopters who wanted the latest in camera advancements.

Despite not being produced for long, the Minolta-ER did little to stop the progress of automation at Minolta. In 1965, the company would introduce the Electro Shot, a 35mm rangefinder camera with fully programmed automatic exposure, and in 1971 the X-1 which was the first SLR with an electronically timed focal plane shutter with aperture priority automatic exposure.

As we all know, auto exposure and other types of automation would quickly become the norm and by the end of the 1970s, nearly every camera had the feature. When looking back at these early implementations of AE, it is interesting to see the limitations, and what photographers had to contend with in order to make it work. While a modern photographer would see a camera with a single, or limited range of shutter speeds, and a single AE mode as a limitation, in the early 1960s when these cameras were making their debuts, they were seen as technological marvels, hinting at an exciting future for more and more advanced cameras.

Today, Minolta SLRs enjoy a positive reputation with successful cameras in the SRT and X-series being some of the more popular cameras for collectors and shooters. Very little is written about Minolta’s lone leaf shutter SLR, but it’s historical significance and odd combination of features makes it a compelling addition to any collection. Despite being built with a good build quality, the complexity of leaf shutter SLRs means they don’t age well and are likely to no longer to work, so if you do buy one with the intent on using one, I definitely recommend getting one serviced.

My Thoughts

I have a volatile relationship with leaf shutter SLRs. When they work, they are some of the best SLRs ever made. I raved about the Kowa SET-R and Voigtländer Bessamatic Deluxe in each of my reviews for those cameras, but the list of leaf shutter SLRs which were totally inoperable or so unreliable that they couldn’t be used is much, much longer.

So when I had the opportunity to pick up a Minolta-ER in “I don’t know much about cameras” condition, I didn’t allow my hopes to get too high.

Whether or not you knew the Minolta-ER was the company’s first and only leaf shutter SLR before picking it up, one glance at the top of the camera would definitely let you know that something is different about the camera.

Dominating the top plate is a very large and fairly flat top cover for both the pentaprism and selenium exposure meter with an engraved “Minolta-ER” logo facing forward. It is clear that Chiyoda Kogaku wanted people to know what kind of camera this is as the logo faces away from the photographer. To the left of the prism is a fold out metal rewind lever. Unlike most SLRs in which the lever folds out of a knob, the lever here is made entirely of metal and must be folded out before it can be used. To the right of the prism is the cable threaded shutter release, film advance lever, and automatic resetting exposure counter. That the exposure counter automatically resets when opening the camera is a nice feature as this wasn’t standard on all models at the time it was made. Between the advance lever and prism are the words “Chiyoda Kogaku”. The Minolta-ER was produced before and after the company being renamed to Minolta, so some versions of this camera say “Minolta Camera Co. Ltd.” here.

Flip the camera over an we see the rewind release button, centrally mounted 1/4″ tripod socket, and the words “Made in Japan”. Off to the side is a notch in the base plate whcih is there to make film loading easier.

The back of the camera is very bare, with only the round eyepiece for the viewfinder. A black frame around the eyepiece is cosmetic only, and offers no connection point for any kind of viewfinder accessory. A single screw below and to the right of the eyepiece is used to disassembling the camera and serves no purpose for the user. Beyond this, the only other thing to see here is a large piece of body covering on the film door.

The left side of the camera has the sliding lock for the door latch. Like most cameras of it’s era, the film compartment is opened by sliding this latch down and swinging the door open. Pulling up on the rewind knob does nothing. Both sides of the camera have chrome metal strap lugs that are angled forward. Having them face forward like this helps to prevent the camera from falling forward while dangling from a strap. The large depth of the combined prism and meter cover gives the Minolta-ER an awkward looking profile.

After unlocking the film compartment, the right hinged door swings open to reveal a rather ordinary film compartment. The presence of a capping plate inside of the film gate is a tell tale sign of a leaf shutter, but other than that, film transports from left to right onto a fixed and single slotted plastic take up spool. The rewind knob does not lift up to move the fork out of the way, so a notch in the base plate beneath the supply side allows you to easily slide in a new cassette when loading film.

The inside of the film door has a large black metal pressure plates with divots in a grid pattern, which help to reduce resistance as film transports through the camera. A chrome metal roller to it’s side helps maintain film flatness across the geared spindle. The Minolta-ER originally came with foam light seals in both the door channels and on the hinge, which have completely rotted away in this camera, requiring replacement before I could shoot the camera.

Because of the large size of the prism and meter, there is nothing to see when looking down upon the top of the lens as almost all of it is shrouded by the meter. Looking at each side of the lens however, on the photographer’s left side is a slider for selecting aperture f/stops from f/2.8 to f/22, plus an additional position with an orange “A” which puts the camera in shutter priority auto exposure mode.

On the opposite side of the shutter is another slider for shutter speeds from 1/30 to 1/500 plus a position for Bulb. All five shutter speeds are marked in orange, indicating they work in AE mode, but Bulb is white, indicating it will not work with AE on. Neither of the shutter speed nor aperture sliders have click stops and move smoothly, suggesting that in between values can be chosen.

Facing the bottom of the shutter is a focus scale indicated in both feet and meters. Since this is an SLR, the need to see focused distance with the camera to your eye isn’t as necessary as with a rangefinder or scale focus scale, but it’s still an unfortunate location, especially considering nearly every other SLR has it facing up. Finally, in a spot in between the focus and aperture f/stops scales is a small slider for choosing M or X flash sync, or V for the mechanical self timer. As with all old mechanical cameras, it is strongly advised you not try to use the self-timer as it can easily jam things up.

Finally, around the front of the lens, the beauty ring doubles as the film speed dial. ASA film speeds from 10 to 400 and DIN speeds from 11 to 27 are available in a strange arrangement where some numbers are one on side of the opening and others are on the other. Not only is this a strange location for a film speed ring, but how the numbers are arranged is unusual as well. The Minolta-ER does not have an interchangeable lens, but when it was new, was offered with two auxiliary lenses which screwed into the front filter threads, allowing for focal lengths of 35mm and 85mm.

Near the 2 o’clock position around the lens is a small round window which the Minolta-ER’s manual describes as a visual exposure indicator, yet nowhere in the manual does it describe what it does. The metering system on this camera was not functional, so I had no ability to test it and with limited information online about this camera, I cannot be certain what this is used for. Perhaps it’s a way of seeing the meter come to life without the camera to your eye, but I cannot come up with a good reason anyone would need to know that.

The Minolta-ER has what at first appears to be an unusually bright and easy to use viewfinder. It has a large split image focus aide in the center surrounded by a ground glass collar, which both making focusing your image a snap. A small round flag near the upper left corner of the viewfinder image turns green with the camera in AE mode when proper exposure can be made. With the aperture control lever set to the “A” position, if the light detected by the camera’s selenium meter will not result in proper exposure given the chosen film and shutter speeds, this flag remains black and the shutter release is locked. With the camera in full manual position, the shutter lock feature does not work, nor does the camera give you any recommendations for exposure.

I started off the previous paragraph by saying “what appears to be an unusually bright….viewfinder”, and my choice for those words are because the viewfinder screen in the camera is of the non-focusing type. Outside of the ground glass circle around the split image focus age are a concentric pattern of Fresnel circles that extend all the way to the edge of the screen. This Fresnel pattern helps to improve brightness, especially near the corners where there is very little light fall off. In the era the Minolta-ER was made, this type of Fresnel pattern on non-focusing screens was very common, as other cameras like the Zeiss-Ikon Contaflex Super used a similar design. This means the viewfinder is very bright and easy to compose your image with in poor lighting, but it comes at the expense of being able to “see” focus on the whole screen. When shooting the camera, use the entire screen to compose your image, but only the split image and ground glass circles may be used for focus. Whether the lens is in focus or not, the rest of your image will appear sharp and clear, even though the camera may not capture it that way.

In use, this isn’t as big of a con as it might seem, as I suspect a huge number of people detect focus only in the center of an image anyway, and if you are used to shooting rangefinder cameras, the combined image is only in the center anyway. For modern shooters used to later SLRs, this might seem like a big issue, but for first time users of this camera in 1963, they likely preferred the compromise of having an extra bright screen.

It is clear the Minolta-ER is a solidly built, although strange SLR that represents a very short period of Minolta’s history. With the company’s positive reputation building great cameras with even better lenses, how much of what’s good about Minolta made it into this camera, or is it a rare misstep by a company with any otherwise stellar track record? Keep reading…

My Results

This Minolta-ER wasn’t in the most optimal working condition when it came to me. The meter was completely dead, so using it in AE mode was not an option. Even in manual mode, I noticed it would get stuck at 1/30 and 1/60, but 1/125 and up seemed to work okay most of the time. Not wanting to tempt fate, I loaded up a roll of semi-expired Kodak CN400 black and white film and hoped for the best. The week I took the ER out shooting, it was heavily overcast, so my plan was to primarily use the 125 and 250 speeds and guesstimate the exposure as best as I could.

I’ve spent the better part of this review telling you all that’s different about the Minolta-ER compared to the company’s other SLRs, but one area in which the camera is the same, is in the excellent performance of the 45mm f/2.8 Rokkor-TD lens. Of course it performs well, it’s a Rokkor, you might be thinking!

As should be a surprise to nobody, Chiyoda Kogaku was one of the premiere Japanese lens makers of it’s era, putting Rokkor lenses on everything from it’s Autocord TLRs to it’s most basic rangefinder cameras, all of which consistently delivered excellent image quality. The Minolta-ER is no exception as images shot with it show excellent sharpness from corner to corner with no obvious vignetting near the corners and none of the optical anomalies often associated with lesser lenses. Due to condition issues with this particular example, I only ever shot a single roll of black and white film in the camera, but based on my vast experience with other Rokkor lens cameras, I have no doubt that it would have performed well with color film.

Using the camera was mostly an uneventful experience for anyone who has shot an early leaf shutter SLR, but might feel a little strange to those used to more modern SLRs. Most of the camera’s controls are in logical locations like the film advance lever, shutter release, and focus ring. The side locations for aperture and shutter speed control is not typical, but took only a couple of seconds to get used to. The biggest change for someone unfamiliar with this style of camera is the viewfinder, or more specifically, the viewing screen. As was common back then, a thick ribbed Fresnel pattern encircles the split image and ground glass focus aides. This has the benefit of making the entire viewing screen bright all the way to the corners, but on the downside, that you cannot “see” focus outside of the ground glass window.

This was a very common practice on SLRs of it’s era as a compromise allowing you to still see through the lens focusing, while still having a bright viewfinder for composing your image, even in low light. That you couldn’t use the entire screen to see focus wasn’t much of a problem at the time, as rangefinder users were already used to only seeing focus in the center of the viewfinder, and for those SLR users who had more traditional viewing screens, the edges were often so dark, you couldn’t see the edges anyway.

Although this Minolta-ER did work, it was in very poor condition and had many problems. The shutter only operated at 125 and up, and after letting the camera sit for more than a couple of minutes, the diaphragm would stick, requiring me to fire off a wasted frame to get it to fire correctly for the next shot. As long as I kept shooting images in relatively quick succession, it was OK, but I had a lot of wasted frame. Also, the selenium meter was dead, so I could only shoot the camera in manual mode.

This was hardly a deal breaker for me though as I am used to shooting cameras to their strengths. I have handled enough cameras to be able to draw conclusions of what a properly serviced Minolta-ER might have handled like, and I’d say it’s pretty good! With an original retail price of $120, the Minolta-ER would have been an affordable entry into both Single Lens Reflex cameras, and automatic exposure, both of which five years earlier, were only available on the most expensive models.

The Minolta-ER is definitely an odd duck in the history of Minolta. It was a historically significant camera in the company’s move towards more automatic operation, and although it wasn’t produced for long, was likely seen as a proof-of-concept for the company as they would later revisit and improve the implementation of auto exposure in later cameras.

These cameras were produced in low numbers, which makes them difficult to find today, especially in working condition. Whether you like leaf shutter SLRs, are a fan of Minolta, or just like cameras with firsts, the Minolta-ER is worthy of being added to your collection. If you can shoot it, then great, but if not, that’s okay too!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Minolta_ER

https://earthsunfilm.com/vmlp-11-the-minolta-er-strange-quark/

http://www.subclub.org/minman/er.htm

https://www.digicammuseum.de/gechichten/erfahrungsberichte/minolta-analog-slr-er/ (in German)

http://www.collection-appareils.fr/x/html/page_standard.php?id_appareil=11507

The Mec 16 SB with a built-in Gossen lightmeter was the first camera to offer through-the-lens metering. 1960

That camera was not made by Minolta. There were other metered cameras with and without TTL metering before the Minolta-ER.

Great review, Mike! I just wanted to point out that Minolta’s first Hi-Matic had automatic exposure with no manual control, and it came out three years before the Electro Shot.

Jerome at Earth, Sun, Film wrote about his experiences with the Minolta ER here:

https://earthsunfilm.com/vmlp-11-the-minolta-er-strange-quark/

I saw one of these several years ago and being a Minolta collector had to buy it. Never saw it before nor could locate much information. My shutter is slow to react however my meter works. You can see the aperture chosen from the back and when I set the camera on A, pick one speed, then subject the meter to different light, and shoot, I find the aperture does change relative to the light from wide open to f22 when you take a look. However, no green light in the viewfinder. Main issue is the capping plate doesn’t move out of the way for several seconds after pressing the shutter release. Not sure this is a camera I want to dive inside versus an SR.

While I’m not one to discourage anyone from wanting to bring back an old camera from the dead, if given the chance to shoot only a Minolta ER or an early SR, I’d definitely do the SR. I have both an early SR-2 and SR-3 and they are gems. There is something different about the earlier SRs that the later SR-Ts don’t have. In a way, they feel better made, almost like a German camera, much like the original Asahiflex and Pentax AP models have a higher level of quality than the later Spotmatics do. The ER is certainly good, but far less flexible.