This is a Mometta III, a 35mm interchangeable lens rangefinder camera, built in Budapest, Hungary between 1958 and 1962. The Mometta III was part of a series of Mometta cameras that shared the same basic body and focal plane shutter with speeds from 1/25 to 1/500 seconds. The lens mount is the same M42 screw mount as used by a huge number of SLR cameras with a 42mm screw mount with the only change being the addition of a coupling cam for the rangefinder. This means that Mometta M42 lenses cannot be mounted to M42 SLRs as the coupling will interfere with the reflex mirror, however M42 SLR lenses can be mounted to the Mometta, just without rangefinder coupling. The Mometta III was the highest featured model in the Mometta series by having both a coupled rangefinder and an interchangeable screw lens mount. Although an unusually high quality camera from a country not known for a great deal of their photographic production, the Mometta III sold slowly with only about 3200 ever produced.

Film Type: 135 (35mm), 24mm x 32mm exposures

Lens: 50mm f/3.5 MOM YMMAR coated 4-elements in 3-groups

Lens Mount: M42 Screw Mount with Special Mometta Rangefinder Coupling

Focus: 0.9 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: Z (Bulb), 1/25 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Cold shoe and M and X Flash Sync, 1/20 X-Sync

Other Features: None

Weight: 568 grams / 458 grams (body only)

Manual: None

How these ratings work |

The Mometta III is an unsuspecting cool and capable camera in a rather mundane body. One of the highest spec cameras from the Hungarian camera industry, the Mometta III has a coupled rangefinder, focal plane shutter, and supports interchangeable lenses via its M42 lens mount. Even though it is a rangefinder, it can accept M42 SLR lenses, albeit without rangefinder coupling. Still, this gives the Mometta III a level of lens flexibility not commonly seen on other mid century 35mm cameras. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 30% | |

| Bonus | None | ||||||

| Final Score | 10.4 | ||||||

History

The histories of many different countries camera industries are well told, and something I’ve covered extensively on this site. There is no shortage of information regarding cameras from Germany, Japan, the United States, Ukraine, Russia, even less common camera producing countries like France, Italy, and Czechoslovakia, but one country that I haven’t yet touched is Hungary.

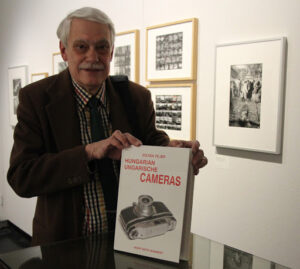

The reality is that Hungary has a deep and rich history that had it not been for being on the wrong side of World War II and Soviet occupation afterwards, might have been a highly influential country through the rest of the 20th century and perhaps even today. I won’t attempt to cover the entirety of the Hungarian photo industry as it is quite a bit deeper than I had anticipated, but if you’d really like to learn all you can, I highly recommend the book, “Hungarian Cameras” by Zoltán Fejér. This 180 page hardcover book is written both in Hungarian and English, and tells the tale of the entire industry from the 1830s to the late 1960s when the Hungarian photo industry was dismantled.

Picking which parts of a whole country’s history to write about is a difficult task, but I think a good starting point for someone who needs a baseline is József Petzval, creator of the Petzval lens which is considered by many to be the first portrait lens and one that inspired lens design for over a century before it was first created. Petzval was born in the town of Szepesbéla in the Kingdom of Hungary in 1807 and studied at the University of Vienna in 1836. His primary area of work was in mathematics, but in 1837 branched off into areas of acoustics and optics. In 1840, he created his first lens, which was initially used by Peter Wilhelm Friedrich von Voigtländer in his optical designs. A bitter dispute between Petzval and Voigtländer over who should get full credit for the lens was never truly resolved, and although Petzval would continue to study and teach mathematics at the university level, never fully realized profits from his design.

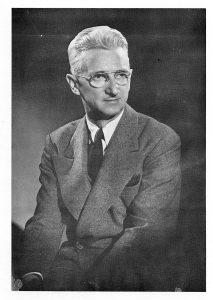

A second key contributor to the photographic industry came in the early 20th century by a man named Joseph Mihayli. Born in 1889 to Joseph and Maria Mihayli in Apatin, Hungary, Mihayli emigrated to the United States in the summer of 1907 with his older brother Frank, winding up in the St. Louis area. There, both Mihayli brothers got jobs at the Wissler Instrument Corp. The younger Mihayli got to work on tool design, his most notable project being a new type of transit used for surveying and other measuring systems.

Over the course of the next 15 years, Mihayli would take jobs working for Bausch & Lomb in Rochester New York, Crown Optical Company, and then finally Eastman Kodak. Shortly after accepting a new position at Kodak, Mihayli’s superiors recognized his considerable talent and experience and gave him the freedom to work on whatever projects he liked.

Over the course of the next few decades, Joe Mihayli created some of Eastman Kodak’s most innovative and important cameras of the 20th century. One of his earliest achievements was the Super Kodak 620, recognized as the first camera with auto exposure. Other designs he worked on were the Kodak Bantam Special, Medalist, and Ektra. In his later years, his ideas for exposure automation and motor drives were implemented into a great deal of other Kodak products and those developed by other companies. While Mihayli is not a household name today, or held in the same regard as other innovative camera designers like Oskar Barnack, August Nagel, Masahiko Fuketa, or Yoshihisa Maitani, his contributions were nonetheless as important.

Although Petzval and Mihayli had the bulk of their successes working in countries other than Hungary, their achievements nonetheless inspired and helped to build up the Hungarian optical and camera industries. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a large number of independent workshops started building all manner of photographic equipment from the most basic accessories to full blown photographic studios.

In the early 20th century, Hungary had a fledgling photo industry comprised with a multitude of small workshops designing small box and other simple cameras, but by the 1920s, two leaders in the industry began to emerge. The first was Gamma Technische AG, “Gamma Technical Company”, founded by István and Zoltán Juhász whose first products were small electrical devices and other precision tools. Gamma would form an optical division in 1935 called Gamma Finommachanikai es Optikai Muvek, whose products included simple lenses and other optical equipment.

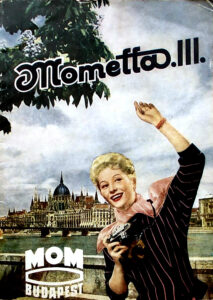

In 1921, a second firm, called Suss Nandor Precizios Mechanikai es Optikai Intezet Rt, (Nandor Suss Institute for Precision Mechanics and Optics Ltd) whose primary duty was presumably lens making. In 1939, the company’s long name was shortened to Magyar Optikai Muvek Rt. (Hungarian Optical Works, Ltd), and was frequently referred to by the abbreviation of its name, MOM.

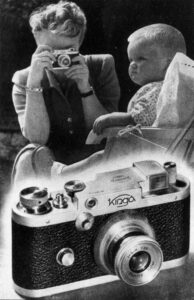

Together, Gamma and MOM produced a great deal of optical products and accessories for the Hungarian and German camera industries. During the war, production shifted to the manufacture of goods for the Hungarian military, but unlike in Germany where most companies stopped development of new photographic goods, in Hungary at the Gamma plant, work got underway for a revolutionary new 35mm rangefinder camera prototype with a fast f/2 lens, coupled rangefinder, a horizontally traveling metal blade shutter, and a unique focus mechanism with a movable prism that could reflect the light from the lens to a piece of ground glass, similar to the design used in the Corfield Periflex.

In 1943 the Kino Gamma prototype, or Kinga for short was shown. The camera had a remarkable design and features unlike any that had come before it. Sadly, during the war, nearly 70% of Gamma’s workshops were destroyed, so wide scale production never commenced. After the war, both Gamma and MOM would resume production, albeit at a much reduced capacity. In the years between 1945 and 1947, another interesting prototype called the Duflex would be created, which had the general shape of a rangefinder camera, but through clever packaging of mirrors, had a reflex viewfinder, similar to an SLR. Although not technically an SLR, the camera allowed for through the lens composition and focus. Gamma would attempt to market the Duflex outside of Hungary, but various combinations of cost, challenges with production, and a general challenge of getting anything exported out of central Europe in the aftermath of World War II ended that fantasy. An estimated 535 Duflexes were reportedly made.

Around this time, MOM had begun producing simpler, and less ambitious cameras than Gamma with models like the the 35mm Kinobox and roll film Pajtas box cameras. In 1952 however, with the expiration on Leitz’s Leica patents, work began on an all new, 35mm rangefinder. Complex designs as seen in cameras like the Kinga and Duflex were scrapped for simpler cloth focal plane shutters, and standard coincident image coupled rangefinders. In the summer of 1953 an unnamed prototype camera was shown with a trapezoid body, angled film transport, and coupled rangefinder. The angled film transport meant that the film had to pass through two 45 degree turns before crossing the film plane, which is thought to provide better film flatness as there is more tension on the film as it passes the plane, but it also allows the supply cassette and take up spool to be tucked into the corner, allowing for a less wide body. The lens on the prototype was a fixed Tessar style 4-element in 3-group design called the Ymmar, which is a name taken from that of the lens designer, Újvári Imre.

The new camera was later given the name Momikon and a preseries of production models began in September 1954, with a public unveiling on October 12, 1954. A total of 500 preseries cameras were made, and differ from all later cameras in that the minimum focus distance was 0.8m instead of 1m like on all other versions of the camera. A second series of Momikon cameras was produced in March 1955, and two more batches produced until those with serial numbers beginning with 50x xxx, at which time the name of the camera was changed from Momikon to Mometta. The reason for the name change is unclear, but it is believed that it was to avoid a copyright issue with Zeiss-Ikon, but in his book, Zoltán Fejér says this is undocumented.

Production of the Mometta steadily increased throughout 1955 and 1956 and remained a popular choice for Hungarian photographers. During this time, Hungary was very closely tied to the Soviet Union and the Soviet controlled German Democratic Republic (East Germany). As such, almost all cameras imported into Hungary were Soviet or GDR models. In an advertisement dated October 1957, available cameras for purchase were the Zorki S for 2200 Ft (the Forint was the currency of Hungary from 1948 and on), FED-2 for 2600 Ft, Zorki 4 for 4200 Ft, KW Praktica FX for 4700, and Exakta Varex for 8000 Ft. Each of these prices were several months worth of salary for the average Hungarian worker at 800 Ft per month. The Mometta had an affordable price of 1494 Ft, although strangely.

By far, the closest competitor to the Mometta was the GDR built Carl Zeiss Werra which sold for right around the same price. By 1957 though, the Werra was steadily improving with features such as a coupled exposure meter and interchangeable lenses. The Mometta was quickly becoming outdated and MOM knew they had to act fast to update their model.

The first update came a mere 5 days after the 1957 Leipzig Spring Fair and addressed one of the biggest complaints of the original Mometta’s design, which was its bottom loading film compartment. Although many German and German inspired cameras had bottom loading film compartments, due to the Mometta’s non linear angled film compartment, loading film into the camera was a challenge. A new model, called the Mometta II would soon be available with a removable back, similar to the Zeiss-Ikon Contax rangefinder. The new film back required a change to the location of the lock for opening the film compartment from one side to the center of the bottom plate. In the place of where the original lock was a second tripod socket in its place. One final cosmetic change to the camera was that for the first time, the name “Mometta” appeared on the top plate of the new model. Previous cameras, including the original Momikon only had a MOM logo.

Although the new film back was a nice upgrade to the original design, the Mometta was still lagging behind other cameras like the GDR Werra that was also available in the country. In an effort to stay relevant, another new model called the Mometta III would be released in November 1958 with a fully flash synchronized shutter, but also an interchangeable lens mount.

The lens mount is something that I feel has an interesting story, but Zoltán Fejér’s book spends very little time explaining it other than to say that in order to use the M42 SLR mount, a 9mm flange extension was added to the front of the camera to match the flange focal distance of M42 SLR lenses. On one hand, a huge number of M42 SLR lenses already existed and were plentiful at the time, immediately expanding the selection of compatible lenses that could be used on the camera, the lack of a rangefinder coupling meant that these SLR lenses would only be scale focus only and anything other than 50mm would require an auxiliary viewfinder.

At the same time as the release of the Mometta III, one final model, called the Mometta Junior was released. The Junior model had the same interchangeable lens mount and flash synchronized shutter, but lacked a rangefinder. In a promotional leaflet created for the Mometta Junor, a 35mm f/4 and 75mm f/4 lens was announced for the camera. A third 135mm f/4 was reportedly in the works, but has never been seen as it likely never made it past the “planning” stage. It is not clear if any of these lenses would have had the rangefinder coupling for the Mometta III, because if they didn’t, these would be nothing more than “normal” M42 screw mount lenses.

Both the Mometta III and Mometta Junior models were less successful than planned, with only about 3200 Mometta IIIs and 1800 Mometta Juniors made. The cameras stayed in production until 1962, seemingly to keep new stock on hand, but for most Hungarian photographers wanting an interchangeable lens 35mm camera, they certainly chose other options.

While the Mometta series was in production, MOM produced a number of other models from a simple stamped metal box camera called the Fotobox, to a more compact 35mm rangefinder called the Virax 35. The company even attempted to throw their hat into the 35mm SLR business, developing a prototype called the Correcta Reflex which never made it past the prototype stage.

MOM, and the rest of the Hungarian photo industry would continue to linger on throughout the 1960s, but economic changes and political pressures put less of an emphasis on producing cameras and lenses. Instead, MOM would turn their sights towards industrial machinery and electronic production.

Finding information about the Hungarian photo industry in the late 20th century was very difficult as apart from Zoltán Fejér’s book, there is hardly anything online. A defunct website dedicated to the history of MOM Budapest suggests that the company ceased to exist after 1998.

Today, cameras like the Mometta typically fly under the radar of many collectors, not because of any inherent problems with the camera, but rather a lack of knowledge of them and the Hungarian photo industry. While Zoltán Fejér did a fantastic job of researching and documenting the Hungarian photo industry, I don’t know that it has trickled down into the general knowledge of the cameras that came from this country.

Which is a shame as the Mometta III is quite a fascinating little camera, and after reading about other Hungarian cameras like the Kinga, Duflex, and Virax 35, I would love to find more of these cameras. As it is, I am happy to have this model in my collection and if you ever find yourself in a similar situation as I was and one just falls in your lap, don’t dismiss it as another generic German wannabe. These are capable cameras with a fascinating story to tell.

My Thoughts

The Mometta was not a camera that was on my radar until I happened to come across this one. Even after seeing it, I assumed it was some little known German brand that wasn’t very exciting.

It wasn’t until after I checked mikeckma…I mean, uuuh, Google for some information when I realized this Hungarian camera was not only not German, but a pretty decent little shooter.

The Mometta is a compact little that is unusually thick for a rangefinder, almost like a backwards Exakta. As I would later learn, the thickness of the camera is so that the 42mm screw mount matches that of M42 SLR lenses, making this one of a very small number of rangefinder cameras that can use SLR lenses without any sort of adapter.

The build quality is good, equally on par with other “B-Level” German brands like Altix, Paxette, or Futura and seems like with regular service is capable of a lifetime of service. The chrome plating has more of a matte finish that most cameras, but has held up well, with very little pitting or degradation. Whatever was used for the body covering has held up well, showing no signs of peeling or cracking.

Up top, the Mometta has all its controls in the usual locations you’d expect to find them. A small pop up rewind knob is on the left. On a raised portion of the camera which you can tell was intentionally designed to mimic the shape of a certain German rangefinder, is where you’ll find the accessory shoe, and to its right, the shutter speed selector. The Mometta has indicated speeds of 1/25 to 1/500 plus Z, which means Bulb, and a red lightning bolt between 25 and Z, which is the shutter’s X-sync speed. The Mometta lacks any slow speeds below the X-sync setting, which I assume means 1/20.

On a lowered level to the right, is the combined film advance knob and exposure counter. The exposure counter is additive, showing how many exposures have been made, and must be manually reset after loading in a new roll. Below and to the left of the knob is the cable threaded shutter release button with a film transport lever beneath it. I found the location of the shutter release to be rather cramped in this location. In addition, being so close to the rear edge of the camera requires you to bend your finger backwards a bit more than feels comfortable. It is not impossible to use, but certainly isn’t pleasant either. With the lever moved in the direction of the letter “V”, transport is deactivated for rewinding the film. With it away from the “V”, the camera transports film as normal.

The camera sides are symmetrical, but otherwise have nothing to see, not even strap lugs. The rear of the camera is equally barren as well, with nothing more than the round eyepiece for the viewfinder in the upper left corner. A (probably) unintended side effect of the camera’s thick shape is that the backwards angled sides fit comfortably in your hand, allowing you a secure grip on the camera while holding it.

The base of the camera has a folding door lock in the center, flanked by twin 3/8″ tripod sockets on each side. Other than giving a good look for those who love symmetry, I can’t really come up with a good reason to have two tripod sockets other than maybe it gives you a little flexibility in how it mounts in tight situations. The film door lock has two settings, the letter “Z” for locked, and “I” for unlocked.

With the door unlocked, the entire back and bottom come off in one piece to reveal the film compartment. Film transports from left to right onto a removable metal take up spool. Due to the tapered design of the camera back, the take up spool is tucked in deep into the corner and is rather difficult to reach without first removing the spool. Even after attaching the leader to the spool, fitting it back into the camera without having the film leader come off is rather awkward.

Other than that though, the rest of the film compartment works as usual. I found the presence of the cloth focal plane shutter to be unexpected as the outside design of the camera suggests a leaf shutter. Inside the film door is an oval shaped metal pressure plate which when pressed, goes into a recess in the film door. The camera’s serial number is engraved into the film gate beneath the shutter opening. Finally, there are no cloth or foam light seals to go bad and need replacing.

Looking down upon the MOM Ymmar lens, its controls look very much like an SLR lens, which in fact, it basically is. Like many 1950s SLR lenses, a ribbed aluminum focus ring is nearest the lens mount and has distances from 1 meter to infinity engraved. A depth of field scale is closest to the camera body. Near the front of the lens is the aperture ring with selections from f/3.5 to f/16. The Ymmar lens is neither preset, nor does it support an automatic diaphragm, not that it needs to.

Up front, the Mommetta has two flash sync ports to the left of the lens. The top port has a red ring around it and is for electronic flashes, and the bottom has a green ring which is for flashbulbs. The Mometta III uses the M42 lens mount, but since this is a rangefinder, each lens made for the Mometta has a rangefinder coupling ring, similar to M39 rangefinder lenses. This means that these lenses cannot be used on M42 SLRs as the lens itself will come in contact with the reflex mirror, but M42 SLR lenses can be used on the camera, just without the coupling. Rotating the lens counterclockwise removes it, and clockwise tightens it.

Nearly every M42 SLR lens will fit on the Mometta and will focus correctly, however since SLR lenses won’t have the rangefinder coupling, you’ll need to focus either using an accessory rangefinder, or get good at estimating distances. This wouldn’t be an issue for wide angle lenses which have good depth of field, but telephoto lenses could be problematic. Of course anything other than a 50mm lens would also need an auxiliary viewfinder to as the main viewfinder only shows a 50mm image. If you wanted to stick to 50mm though, you could still use the main viewfinder with something like an f/1.4 Yashinon and get the benefit of a much faster lens than the stock f/2.8 Ymmar that comes with it. Clearly, the creators of the Mometta III were aiming to capitalize on the large number of easily available M42 lenses coming out of East Germany after World War II.

The viewfinder on the Mometta II is surprisingly good. It isn’t very large, but unlike many 1950s 35mm rangefinder cameras with tiny viewfinders, I can still see all four edges of the viewfinder while wearing prescription glasses. In addition, the rectangular rangefinder patch has good contrast via a yellow tinted filter which makes it easy to see. Beyond the rangefinder patch though, there are no frame lines or anything else to see in there.

What I initially dismissed as an uninteresting and basic German rangefinder turned out to be a very cool camera from a country I had little experience with. The idea that a 35mm rangefinder camera could use SLR lenses and still focus correctly is super cool. That it has a focal plane shutter means there is no leaf shutter to interfere with adapting lenses, and with good build quality and a decent coupled rangefinder, dare I say that the Mometta III is a capable but economic alternative to much more expensive German rangefinders. Please don’t call it a Leica copy, but it does check off many of the same boxes as a Leica.

With increasing excitement for this camera, all I had left to do was shoot it. What kind of images would it make? Keep reading!

My Results

The Mometta came to me in fair condition. Cosmetically, it was nice, but all of the camera’s controls were stiff. The focus and aperture rings took a bit more effort to turn than I was comfortable with, but with a bit of use, seemed to loosen up. The shutter was sluggish too, but like the lens, did seem to loosen up after a while. It would consistently get stuck at 1/25, and with the back removed looking through the film compartment, the curtains weren’t separating at 1/500, but from 1/50 to 1/200, things looked okay so I decided to just stick to those three speeds. If I really wanted to put several rolls of film through this camera and shoot it reliably, it would need a full CLA for proper operation, but I have far too many cameras to test, and sadly, this camera would likely only ever get a roll or two from me, so I decided to hedge my bets, load in some film and hope for the best. Strangely, I landed on bulk EFKE 25. In hindsight I probably should have went with Kodak TMax 100 like I usually do, but was in an “Iron Curtain” mood, so I went with the Croatian film.

As expected, I struggled with the shutter on this camera. Although I had thought it was firing fine most of the time, as it would turn out, more than half the roll either didn’t expose at all, images would overlap, or the shutter hung up, causing one half of the image to be pure white, and the rest just blown out.

The good news is I did get a couple decent shots as seen above. The Ymmar lens produced okay looking shots. Some internal haze definitely added some softness to the images, especially those in which the sky was present. My one attempt at an indoor shot actually came out quite good. The lack of an overpowering source of light allowed the image to have good contrast with sharp details.

I’ve found no technical details on the makeup of the lens, but I’ll guess it is a Tessar copy. I saw a slight bit of vignetting in the outdoor shots, but nothing that struck me as offensive. Sharpness was good in the center, but once again, there was a good deal of softness which negatively impacted contrast, due to lens haze. Had this lens been crystal clear, I suspect the images would have looked like any other Tessar out there.

Despite some flaws with the camera, I felt as though the Ymmar lens did a good enough job for most people, however I would be missing a great opportunity if I didn’t take advantage of one of the coolest features of this camera, which is its ability to use M42 SLR lenses, so I wanted to shoot a few images using some other kind of lens.

While looking through my selection of lenses, I wanted to pick something that was period correct for the Mometta and might actually have been around when this camera was still being sold. I had a couple options, but not wanting to shoot another 50mm f/2.8 Tessar, instead I chose a Carl Zeiss Jena Tessar 40mm f/4.5 M42 lens which came to me on a Contax D SLR. As expected, the SLR lens screwed right into the Mometta no different than on the camera it came with. Since this is an SLR lens, it does not have the rangefinder coupling of the original Mometta lens, so I would have to rely on scale focusing. To help me compose with the 40mm focal length, I mounted a Leitz 5cm auxiliary finder which when I look outside of the framelines, approximates a 40mm focal length. Knowing of the camera’s shutter and film transport issues, I didn’t want to sacrifice an entire roll of film for this test, so instead I split a roll of fresh Fuji 200 with another camera.

As I expected, the Tessar 40mm f/4.5 lens delivered optically better results than the Ymmar lens by virtue of it being in better condition, and without internal haze. The 40mm focal length also allowed for greater depth of field which helped me in guess focus since the rangefinder is no longer coupled.

Unfortunately, the shutter issues continued while shooting this roll, with uneven exposure on the right side of the frame but also with a light leak that started to appear on some shots. I attempted to take a mirror selfie like I do with most cameras, but by the time I did those shots, the shutter was no longer firing.

With the unfortunate realization that these likely would be the last shots ever taken with this particular camera, I still felt as though I got a sense of what it would have been like to shoot when it was new, and in perfect working condition. That the designers of this camera chose to expand its lens selection by making it compatible with M42 SLR lenses was an incredibly good idea, and one that I wish other companies would have tried as it gives the Mometta an additional level of capability that is often lost on most small production mid 20th century rangefinders.

Carrying the camera around while shooting it was a pleasant experience. I really liked the shape of the body. With the angled back of the camera which was necessary to get the correct flange focal distance to accept SLR lenses on a rangefinder body, the camera felt very comfortable in my hands. Compared to a screw mount Leica, the Mometta is almost a full inch narrower. Even when compared to a 1950s Kodak Retina, it is slightly narrower as well making the camera quite convenient to hold. The thickness of the body, plus the lens negates any ability to slide in a shirt pocket, however.

I found the viewfinder to be basic, but good. For the condition issues this camera and lens had, the viewfinder was pretty clear, the rangefinder had excellent contrast, and most importantly, it was accurate. I had no issues with measuring focus while shooting my test roll with the rangefinder coupled Ymmar lens.

Despite the shutter’s poor condition which resulted in uneven exposure, the choice of a focal plane shutter as opposed to a leaf shutter was a wise one as making interchangeable lens cameras with leaf shutters was not an easy task. The focal plane shutter almost certainly simplified the design of the camera allowing it to be sold cheaper. In addition, the familiar “snick” sound that a camera with this shutter makes as it fires reminded me of higher end cameras like Leica and Nikon rangefinders.

Without a doubt, the camera’s best feature is its compatibility with SLR lenses. I suspect photographers who considered one when new saw this as a big plus compared to other interchangeable lens rangefinders which by the late 1950s, increasingly used more proprietary bayonet mounts. If you had access to a wide angle or telephoto Zeiss, Meyer-Optik, or Steinheil lens, it would work great, all you needed was a universal viewfinder. Even better, if you were to build up a collection of M42 lenses for this camera and then wanted to actually get a Praktica SLR, or even one of those new fangled Japanese SLRs, you could keep using the same lenses!

I don’t know how many of these cameras were ever made, how well they sold, or if any make it out west to the United States, but I am happy this one did. It wasn’t in the best condition, and definitely could use an CLA and a better lens, but for what it was, it worked well enough to form an opinion on it, and that opinion is a good one. Congrats Hungary, my first experience with one of your cameras was a good one!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Mometta

https://camerajunky.blog/2016/10/24/mometta-ii/

http://forum.mflenses.com/ymmar-35-50-mm-mometta-junior-m42-t47066.html