This is an Olympus OM-2, a 35mm Single Lens Reflex camera made by the Olympus Corporation from 1975 – 1984. The MD in the name means it has the Motor Drive provision on the bottom plate. The OM-2 was the follow up to the extremely successful OM-1 from 1973. It added aperture priority auto exposure with an electronic shutter and a unique Silicon Blue Cell exposure meter that took a reading off reflected light off the film plane. The OM-2 shared the earlier model’s small and lightweight body, while retaining full manual control, interchangeable focus screens, and lenses. The OM-2 was a popular third option to Nikon and Canon models of the time, and was heralded for it’s small size, innovative meter, large and bright viewfinder, and excellent F.Zuiko lenses.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens Mount: Olympus OM Bayonet Mount

Lens: 50mm f/1.8 Olympus F.Zuiko AUTO-S Coated 6-elements

Focus: Fixed SLR Prism

Shutter: Focal Plane Cloth

Speeds (Manual): B, 1 – 1/1000 seconds

Speeds (Auto): 120 – 1/1000 seconds, stepless (Yes, thats 120 seconds auto exposure!)

Exposure Meter: Dual Silicon Blue Cell TTL OTF (Off the Film)

Battery: 2 x S76 Silver-Oxide or Alkaline Battery

Flash Mount: Hotshoe and PC-X connector

Weight: 703 grams (w/ lens), 525 grams (body only)

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/olympus_pdf/olympus_om-2.pdf

My Final WordHow these ratings work |

The Olympus OM-2 was a state of the art camera that offered a long list of innovative and high tech features in a small and lightweight body that was unlike anything in the market upon it’s release. It was one of Olympus’s most successful cameras and would remain in production until at least 1984. As a user, it is still a very capable camera that is still popular with those who still shoot film today. While my first experience didn’t leave me with many warm and fuzzy feelings about it, I see the appeal that this camera has for so many people. If you are looking for a really nice and easy to use example of a 1970s SLR, you could do a lot worse than the OM-2. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0% | |

| Bonus | +1 for it’s incredibly small size and innovative feature set | ||||||

| Final Score | 10.0 | ||||||

History

Olympus was founded in Tokyo, Japan on October 12, 1919 as K.K. Takachiho Seisakusho, or Takachiho Works Co., Ltd. in English by Yamashita Takeshi. Mr. Yamashita had previously worked for an industrial manufacturing company known as Tokiwa Shōkai who operated in many Japanese industries at the time.

Takachiho Seisakusho was formed using financial support from Tokiwa who maintained a share of the new company’s ownership and handled all of the company’s marketing.

Although Japan’s industry was growing quickly in the early part of the 20th century, it still relied heavily on many imported products from Europe and other parts of the world. Takachiho Seisakusho’s first products were microscopes and thermometers based on German designs of the time. An early goal of the company was to compete with the likes of Leitz and Zeiss who up until this point had gone unchallenged in these industries.

Takachiho Seisakusho would release the first Japanese made microscope in March 1920. It was given the name “Asahi” which stands for “morning sun” which is the symbol of the Japanese people. The Asahi was made with a gunmetal body, and sold for 125 yen. The Asahi was sold under the brand name Tokiwa in 1920, but the very next year, the brand name was changed to Olympus. In total, Takachiho Seisakusho had 7 different models available for a variety of industries, one of the biggest of which was the Japanese textile industry. Tokiwa/Olympus microscopes were very successful, and a source of pride for the company and all of Japan.

The company would continue to improve and innovate new microscope designs throughout the rest of the 1920s and well into the 30s where the Olympus brand became known worldwide as a leader in microscope and optical design.

In 1933, Takachiho would sign an agreement with the Japanese Navy as an exclusive maker of microscopes and other optical equipment. One of their products was a device called the Olympus PM I and II which allowed photographs to be taken through a microscope. It wasn’t exactly a camera by traditional standards, rather an apparatus that consisted of a prism, a ground glass, a rudimentary shutter, and a dark box. It would make plate film exposures that were 56mm x 93mm. A later version of this apparatus used a bellows instead of a dark box.

Perhaps due to the success, or at least some level of interest, in this rudimentary microscope camera, in 1935 Takachiho would diversity it’s portfolio by developing it’s own optical lenses. Initially operated as a separate, but co-owned company known as Mizuho Kōgaku Kenkyūjo, the company’s first lenses were released in 1936 and were based off Zeiss Tessar formulas and came in focal lengths of 105mm and 75mm. These lenses were given the name Zuikō as a result of a contest among company employees to select a name.

Mizuho’s original intent was to market and sell their lenses as stand alone products, but could not find any interested parties to buy them. In an effort to drum up interest in their lenses, Mizuho decided to sell the lenses together with a camera body to increase interest in their design.

Without any actual expertise in developing camera bodies or shutters, Takachiho would partner with Miyazaki Shizuma who was the owner of yet another Japanese optics company called Proud-Sha and would use a model they made called the Semi-Proud, a 6cm x 4.5cm folding camera that itself was based of the German made Balda Baldax.

As a result, in 1936 Takachiho would package it’s own Zuiko lenses made by Mizuho Kōgaku, with a camera made by Proud-Sha, and would market it under Takachiho’s Olympus name as the Semi Olympus.

It’s worth mentioning that many Japanese 6cm x 4.5cm folding cameras had the name “Semi”, which is another way of saying “half” for half frame 6cm x 9cm which was the common size for 120 format roll film.

In 1937, Takachiho would release the Semi Olympus II which was inspired heavily by the original Proud-Sha designed Semi Olympus, except this time the body, shutter, and the lenses were all made in house by Takachiho.

It is said that Yamashita Takeshi had a great admiration of Zeiss and wanted to compete with them with their own quality lenses and cameras. The Zuiko was based off Zeiss’s Tessar formula but was not an identical copy, and the Semi Olympus II was built to compete with the Zeiss Ikonta which was also not an exact copy. This was in contrast to other Japanese companies like Canon and Minolta who made near identical copies of German cameras with only minor differences. Takeshi wanted Takachiho’s products to stand alone in the marketplace and be 100% Japanese designs, and not just another German copy.

At this time, there was a great deal of innovation in the Japanese camera industry, and Takachiho would design a revolutionary new 35mm rangefinder known as the Olympus Standard, which was going to compete with the Zeiss Contax rangefinder, but the complexity of the design and the onset of war caused production of the Standard to be halted after only 10 prototypes were made.

World War II changed the entire Japanese optics industry, including Takachiho who fell under control of another Japanese optics company called Ataka Shōkai in 1942. Founder and CEO Yamashita Takeshi would resign in 1943 and the company’s name would be changed to Takachiho Kōgaku Kōgyō K.K. From 1940 – 45, the only model being made was the Olympus Six, a 6cm x 6cm folding camera which was also made for the Japanese military.

Then in 1945, several of Takachiho’s factories, including one in Hatagaya where Takachiho’s shutters were made, were destroyed by US bombers, halting production for at least a year. Production of the Olympus Six resumed in 1946, and then in 1948, the Olympus 35 would be introduced which was the company’s first ever 35mm film camera.

On January 1, 1949, the company’s name would be changed once again to Olympus Kōgaku Kōgyō K.K. which was the first time the company was officially known as Olympus.

Throughout the 1950s and 60s, Olympus would release a wide variety of folding, TLR, and solid bodied full frame and half frame 35mm cameras that were highly successful. At the time, Olympus was one of Japan’s premiere optics companies. Despite their recent popularity as a maker of cameras and lenses, the company would continue to follow in the footsteps of the original Takachiho’s reputation as a quality microscope maker. Many of the company’s most successful microscopes were designed during this period elevating their reputation as one of the world’s leading microscope makers, a reputation the company still has to this very day.

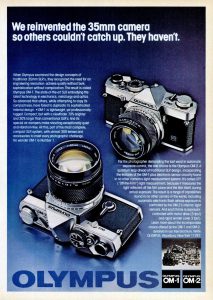

By the early 1970s, Olympus started to fall behind in sales to other Japanese companies like Nippon Kogaku (Nikon), Canon, and Pentax, so the company took on it’s most ambitious task yet. It was going to enter into the highly competitive single lens reflex (SLR) market that was dominated by both Nikon and Canon. Olympus wisely knew that they would struggle to compete with the professional grade Nikon F-series, or the highly regarded semi-pro SLR lines by Canon, Minolta, and several other manufacturers, so instead, Olympus targeted a relatively new market, which was the compact and lightweight SLR market. Until this time, most SLRs were large and quite heavy. Asahi Pentax, and Petri were the only makers of lightweight SLR bodies, but their Spotmatic and Petri-Flex lines were relatively basic models. Olympus wanted to design a whole new SLR system with state of the art features, quality lenses, and high quality, but light weight bodies.

In 1972, the Olympus M1 was released. Designed by a team led by Maitani Yoshihisa who had previously designed the Olympus Pen series, it is said that Yoshihisa was inspired by the Leica M-series rangefinder in designing the M1 as the goal was to have the camera be no larger or heavier than the Leica. In an ironic twist, Leitz got into a legal argument with Olympus over the Olympus M1 name because Leitz already had a model called the M1. As a result, the Olympus M1 was renamed the OM-1 to avoid any copyright infringement. An estimated 52,000 Olympus M1s were sold before the name changed to OM-1, and as such are very expensive and highly sought after by collectors.

The Olympus OM-1 was a huge hit. It was an entirely mechanical camera with a CdS cell exposure meter. It had specially designed air dampers which would quiet down the sound of the shutter firing. It’s body only weight of 510 grams was significantly lighter than other cameras of the day such as the Pentax Spotmatic SP at 621 grams, Yashica TL Electro X at 722 grams, Canon FTb at 740 grams, and Nikkormat FTn at 755 grams (all body only).

The OM-2 followed it 2 years later and was the automatic version of the OM-1 with a fully electronic shutter. It carried over most of the features that made the OM-1 great like it’s compact size, quiet shutter, and compatibility with all OM series lenses and accessories. The OM-2 had aperture priority auto exposure with TTL flash exposure metering. Instead of a traditional CdS meter, it used twin silicon blue cell (SBC) meters which took a reading by measuring reflected light off the film itself at the exact moment of exposure. Combined with a randomized white checkerboard pattern on the back of the first shutter curtain, the meter would detect light reflecting off the curtain using shutter speeds slower than 1/60th of a second before the exposure is made, and then on the film itself after 1/60th of a second. I won’t pretend to fully understand how it worked, but if you’d like a more technical explanation, MIR has a pretty good write up with some illustrations that explain it better than I could. Despite all of these advancements, the OM-2’s body weight increased by less than 10 grams compared to the OM-1.

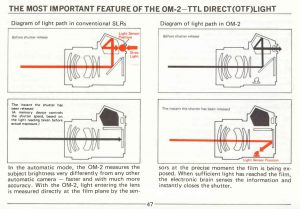

The OM-2’s metering system was advertised as a much more accurate method for measuring light exactly where the film would be exposed, rather than up in the prism or viewfinder like on most other SLRs. The image to the left from the OM-2’s original manual shows a comparison between how a TTL meter works in the OM-2 compared to other SLRs of the time.

By taking a reading at the exact location and moment of exposure, any possible chance of light variation in the time it took the reflex mirror to swing up out of the way and open the curtains is eliminated. This also eliminated the need for a viewfinder blind which was used on some SLRs to block out stray light from entering the viewfinder during long exposures. The metering system on the OM-2 was so accurate that it allowed for automatic exposures of up to 120 seconds, which is unheard of, even today. The longest automatic exposure time on my Nikon D7000 DSLR is “only” 30 seconds.

An interesting side effect of the metering system in the OM-2 is that since the exposure meter can only take a reading at the film plane when the mirror is up, it doesn’t work while the mirror is down. In order for the exposure needle visible in the viewfinder to register a light reading while composing, Olympus had to add two separate CdS meters in the viewfinder. These CdS meters in the viewfinder are only used for the viewfinder, and are not used when calculating exposure as the two systems are completely isolated from each other. Also, according to page 98 of the OM-2’s manual, the two sets of meters have completely different EV sensitivities. The focal plane SBC meters have an EV range of -6.5 to 18, and the viewfinder CdS meters have an EV range of 1.5 to 17. This means that there could be discrepancies between what the CdS viewfinder meter sees and what the two SBD meters behind the mirror see. You could get completely different exposures with the camera in Auto mode, compared to Manual mode, if you trust the match needle.

Here are two magazine articles from May 1976, both announcing the arrival of the Olympus OM-2. The first is a short review from Modern Photography’s “Modern Tests” column in which the camera is put through it’s paces and various specifications are measured.

This second is more of an editorial, “first look” at the OM-2 by Simon Nathan from Popular Photography, who rather unfortunately, misspells Maitani’s name. The article is interesting though in it’s sort of first person perspective look at a very well known camera today, and how it was perceived when it was new.

The OM-2’s huge list of highly capable features, combined with it’s easy to use and compact body made it a huge success. The original OM-2 would receive a few updates through it’s 9 year production run, the first in 1979, called the OM-2N which moved the reset button to the top of the camera and had a revised wind lever and flash attachment. Then in 1984, a heavily redesigned model called the OM-2SP (or Spot Program) would be released and sold for another 4 years, finally being discontinued in 1988. Although the SP model shared the same “OM-2” designation, it featured a revised body, completely different shutter, full Program mode auto exposure, and an LED display inside of the viewfinder.

Today, the Olympus OM-2 has a near cult following. It remains a popular user camera for people still interested in shooting film and is one of the most successful Olympus models of all time. I could not find any information regarding production numbers, but they had to be high. A quick search for “olympus om2” on eBay returned 138 results, so finding one is not difficult for anyone interested in picking one up. Prices fluctuate wildly depending on the condition of the camera and if any lenses or accessories are included. In mint condition, sold prices can exceed well over $200.

My Thoughts

When I was in my early 20s, I was a bit of a gear head. One of my pride and joys was a 1998 Pontiac Trans Am which I still have. I got hooked on modding the car, upgrading the engine, exhaust, suspension, stereo, and just about anything that I could afford. I joined car clubs, raced that car, and made tons of great memories.

For those of you who aren’t very knowledgeable in the world of cars, Pontiac was a division of General Motors prior to their bankruptcy in 2008. They made sister cars to Chevrolet and other GM brands like Buick and Oldsmobile. During that era if you were a GM guy, you generally competed against Ford guys. Mustangs would race Camaros and Trans Ams at the drag strip on an almost daily basis. Although there were some closet gear heads who liked both GM and Ford, they generally wouldn’t admit it in public.

Every once in a while, you’d run into that guy who was neither a GM or a Ford guy, but he was the odd duck who liked the third biggest American auto company, Chrysler. Known as MOPAR in car circles, the Chrysler Corporation also owned Dodge, and until 2000, Plymouth.

GM and Ford were the top 2 American auto manufacturers, and Chrysler was a distant third in terms of sales and popularity. Ask a MOPAR guy though, and he’d tell you that his brand’s products were just as good, or even better than anything else out there.

The same is true in some respects with photography. Nikon and Canon are the GM and Ford of the camera world, and Olympus was Chrysler. I realize I probably just pissed off a bunch of Pentax loyalists….sorry about that, but for the purposes of this analogy, it only works if I mention 3 Japanese camera makers. And yes, there was also Minolta and Konica, but they both went out of business so we’ll pretend that they were AMC and Studebaker.

Nikon, Canon, and Olympus all make what are called “system” cameras. This means that once you bought into a brand, you would continue to buy everything made for their system. Nikon lenses and accessories generally weren’t compatible with cameras made by Canon or anyone else. Sure, you could buy adapters, but most people didn’t do that back then. Like today, system cameras aren’t cheap. It’s said that when buying a new system camera, you don’t necessarily buy into a particular brand for one single camera, but more for the whole system. When I bought my first Nikon, I bought one because I had a couple of friends who also had Nikon cameras, so I could learn from them and borrow their stuff.

When you buy into a particular system, you will invest quite a bit of money because once you start buying other parts for your chosen system, it can get quite expensive to change later on down the road. So it is this reason that Nikon guys generally weren’t interested in Canon, Olympus, or any other brands, and vice versa.

Now, with the proliferation of dirt cheap film SLRs in the used market today, thrifty people like myself have the luxury of picking and choosing models across multiple systems and playing with them. I can buy a Nikon, Canon, and Olympus camera with lens for a tiny fraction of what these cameras originally cost. It would have been insanely expensive for someone in the 70s or 80s to buy one of each just to “play” with them.

So while I had been enjoying trying all these different systems, the Olympus line was one that I didn’t have much of an interest in at first. There gets to be a point when you shoot enough Japanese SLRs, they start to blend together. I had read many glowing reviews of the OM-2 and the whole OM family, but it wasn’t until I stumbled into a resale shop and saw this Olympus OM-2 sitting in a basket of junk. I picked it up and noticed it was very rough looking and it looked like someone had poured vegetable oil on it (at least that’s what I told myself since I didn’t really want to know what kind of oily substance was on this camera). It literally had these yellow drops of oil all over the body and inside the film compartment. I tried to fire the shutter, and it wouldn’t fire. There was no lens attached, so when I looked in the mirror box, I could see the mirror was in it’s up position.

I was about to put it back in the box when I remembered reading online that some 70s SLRs will lock the mirror in the up position if the battery dies. I didn’t have a spare battery on me to test this OM-2, but then I noticed a “Reset” button near the bottom of the lens mount and upon pressing it, the mirror flapped back to it’s down position, and I heard the shutter reset.

Hmm, that seemed optimistic. I cocked the shutter and fired it again, and the mirror stuck in the up position again. I went through the cycle of resetting it and firing the shutter a couple of more times and despite it’s unfortunate sheen of oily residue, I thought that if they’d let it go cheap enough, it just might be worth a shot. I offered the lady at the counter $5 and she said sure. So here I was with my first ever Olympus OM-2 coated in what I hoped wasn’t anything toxic.

I mentioned my recent fortune to my friend Adam from Quirky Guy with a Camera, and lo and behold, Adam had a spare Olympus F.Zuiko 50/1.8 lens sitting around that he’d gladly send my way.

A week or so later, Adam’s lens showed up and with a box of Q-tips and a bottle of rubbing alcohol, I cleaned as much of the oil off the camera as I could. Thankfully, the oil seemed to be only on the outer parts of the camera, and around the inner lip of the film compartment. I did not see that any had gotten on the shutter, which is likely why it was still firing. I grabbed two unused S76 batteries, mounted Adam’s lens and to my surprise, the camera fired right up! The exposure needle in the viewfinder sprang to life, and the shutter sounded accurate!

I mention earlier in this review how one of the biggest selling points of the OM-series was it’s light weight body. Compared to other 1970s SLRs in my collection, the OM-2 is impressively small and light weight. To even suggest that in this tiny little body is a fully featured AE camera with so many advanced features is pretty amazing. I can definitely see why the OM-system was so popular with photographers.

My favorite feature is definitely the viewfinder. It’s combination of size and brightness is impressive considering the era this camera was released. It also features a split image focus aide which is something I prefer over microprism circles.

My favorite feature is definitely the viewfinder. It’s combination of size and brightness is impressive considering the era this camera was released. It also features a split image focus aide which is something I prefer over microprism circles.

On the left side of the viewfinder, you see the exposure needle with a scale that changes depending on the mode the camera is in. Looking at the images to the left and right, you’ll see that there is a see through scale that moves depending on if the camera is in Auto or Manual mode. In Manual mode, the scale only shots a + or a – and it works like any other match needle camera, but when you move the mode selector to Auto, the scale changes, showing shutter speeds from 1 second to 1/1000. This is when the camera is in aperture priority auto exposure mode and the needle will point to whatever shutter speed the camera is going to select. When the camera is switched off, the scale disappears altogether.

Another interesting feature of the OM series was the air dampened shutter system which works surprisingly well. While not as silent as a leaf shutter camera, the sound of the shutter on the OM-2 firing is considerably quieter than other mechanical and electronic shutter SLRs of the day. Since the shutter is electronic, there is no sound of a mechanical governor ticking away while shooting slow speeds. Also since the shutter is electronic, it will not fire at any speed except Bulb with a dead battery.

The OM-2 has a couple of less obvious features too, like a battery check light that will remain steady when the battery is fully changed, and will blink if the camera detects that the voltage of the battery is getting low. The OM-2 body itself does not have a depth of field lever, but all OM-system lenses have such a button on the lens itself allowing you to preview the depth of field if you so choose. The self timer can be partially engaged allowing for a delay of between 4 and 12 seconds, and can also be cancelled midway through it’s travel. The film back is removable, allowing for different kinds of data or bulk film backs to be used. Finally, the focusing screen is interchangeable if you wanted to try out some other type of focusing screen which suggests that Olympus was making an attempt to cater to professionals too.

While I enjoyed the viewfinder and the camera’s small and compact size, I found a few other aspects of it’s layout to be a little awkward. The most significant was the shutter speed collar around the lens mount. Olympus went with a design that is very similar to what Nikon did with it’s Nikkormat series. Instead of a traditional dial on the top plate of the camera, there is a collar ring that entirely circles the lens mount that is used to change shutter speeds. When the camera is in Auto Exposure mode, you don’t need to mess with it, but when shooting in Manual mode, I found myself fumbling with it on more than one occasion.

I think the theory with putting the shutter ring here instead of on the top plate of the camera is that it is in easier reach of your left hand while focusing the camera. You can change focus, aperture, and shutter speeds all with the same hand without taking your eye away from the camera. This works well on the Nikkormat partially due to the larger size of the camera. But this is one area where the Olympus OM-2s small size works against it. The shutter ring feels cramped up against the body of the camera and only gets worse if you have large hands.

Another curious design decision is that on top of the camera where a traditional shutter speed selector would be, is the exposure compensation dial. It offers up to 2 full stops of over or under exposure in 1/3rd stop increments. Exposure compensation dials are certainly useful features, but I don’t know that it should occupy such a prominent location on the camera’s top plate. If you are shooting the OM-2 in manual mode, you could just change the aperture or shutter speeds to compensate exposure, rather than using a dial like that. Then in Auto mode, you’d have to relocate your hand to change it anyway, so there’s really no benefit to it’s location.

I understand the potential benefit for having the shutter speed control around the collar of the lens mount, but on a small camera like the OM-2, I feel it becomes more of a burden than an asset. I will at least acknowledge that as I write this, I have only shot one roll of film through the OM-2. Perhaps with repeated use, this would be something I would get used to, as I’m sure many happy OM-2 owners did back then, but as someone who frequently jumps between different SLRs, I find this to be something I don’t love about the OM-2.

Overall, the OM-2 is quite a nice camera, and I can definitely see why people liked it. There was just enough that was different about it that it didnt feel like a clone of a Nikon or Canon. The F.Zuiko lenses were as good as anything out there, and of course it’s small size and high tech features likely made it a frequently bought model by people who wanted something different than what everyone else was shooting.

My Results

When writing reviews for this site, I often go through various phases of “acquisition”, “shooting”, and “reviewing”. Sometimes I build up a queue of cameras that I want to shoot so that I can get some results from them for a future review. At the time I got this OM-2 working, my queue was quite large, and I had a trip planned to visit Parke County, Indiana, near Turkey Run State Park. I already had about 10 cameras set to go with me that day, but I didn’t want to pass up such a good chance to try out this OM-2, so it was a last minute addition for that trip. I’ll be honest and admit I can’t remember what kind of film I used for this test roll as I didn’t plan it out as well as I normally do with other cameras, so what follows is a gallery of the best shots from that mystery roll of film.

One last thing I should mention is that unlike pretty much every other Japanese SLR from the 70s or 80s, the light seals were still in tact on this camera. It looks like the door deals are all made of a fabric, rather than the foam that normally turns into a sticky mess after several decades. While I still think that replacing light seals is a smart thing to do on any classic camera, it wasn’t necessary on this example.

If there’s one regret that naturally comes with reviewing so many cameras, is that often I do not get to spend as much time as I’d like with a particular model. I have to find the balance of getting a review done and published while still feeling as though I did the best I could given my time and money for a particular model.

There is little I can really say here that would change the mind of someone who already is a fan of the OM-2, and if this review is your first exposure to the model, make no mistake, the OM-2 is an excellent camera with a lot of great things going for it. There is a reason that this model is so highly regarded.

Looking at the images above, I can say they are OK. I think my choice of film was not wise as the images all seem to be somewhat washed out. I regrettably didn’t write down what film I used, but looking at these results, it has to be some type of expired film as these shots are not consistent with the vibrant and colorful images I usually get from fresh Fuji 200 or 400. My favorite image is definitely the one from within the covered bridge, but otherwise I don’t feel as though I did a very good job of capturing any magical moments, but I certainly cannot blame the camera for that.

While shooting with the OM-2, I felt as though the meter was overexposing my shots by at least a full stop, if not more. I noticed my shutter speeds seemed way too slow for the situations in which I was using them, so I shot about half the roll using Sunny 16 and half with AE, and looking at the results, my Sunny 16 shots looked more accurate. This is not entirely unexpected for a nearly 40 year old camera, but it is disappointing considering the technology that went into the OM-2’s “Off The Film” metering system. It would seem that no matter how advanced a system is in the 1970s, it is still subject to the perils of time, not unlike more traditional metering systems in any other number of cameras from the same era.

Since I spent some time with the camera in Manual mode due to the meter, I was forced to use the shutter collar around the lens mount and I just could never get used to it. My only other experience with a camera with a similar shutter selector is the Nikkormat series, but the larger size of those cameras make finding the shutter ring just a tad bit easier. I would have preferred a more traditional shutter speed dial on the top plate of the camera, or with a forward reaching one, like on the Canon EF.

Continuing with my Chrysler analogy earlier, Olympus was not only “third” in an industry dominated by Nikon and Canon, but like Chrysler, it took some risks with design and functionality that the more conservative “big two” didn’t. The compact and lightweight body was Olympus’s Dodge Dart to Chevy’s Nova and Ford’s Falcon, it’s revolutionary OTF metering system was it’s push button transmission to Chevy and Ford’s column and floor mounted shifters, and it’s quality Zuiko glass was it’s Hemi 426 to Chevy and Ford’s 454 and 460 big blocks.

It is clear to me that my experiences with this camera are not shared by the millions of people who bought, and loved them over the years. The OM-2 is a classic design that is still capable of wonderful photography. Olympus did a hell of a job packing so many great features into the OM-2’s tiny body. I thoroughly enjoyed it’s compact and lightweight size, and I really did like the viewfinder. I wonder if my impressions of this model would change if I gave it another shot without the burden of 10 other cameras. I do like the OM-2, but perhaps the worst knock I can give it, is that there are so many other equally great SLRs made by the competition, that in 2017 when you can find these things for fractions of what they cost knew, it’s just easier to own them all!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Olympus_OM-2

http://camerapedia.wikia.com/wiki/Olympus_OM-1/2/3/4

http://www.mir.com.my/rb/photography/hardwares/classics/olympusom1n2/om2/

https://simonhawketts.com/2016/04/30/olympus-om-2-review/

http://quirkyguywithacamera.blogspot.com/2017/03/oh-me-too-what-more-can-i-add-olympus.html

http://120studio.com/film-slr/olympus-om2.htm

http://olympus.dementix.org/Hardware/

http://www.robnunnphoto.com/posts/2011/5/26/the-olympus-om2n-35mm-film-slr-camera-review.html

http://photo.rwboyer.com/2012/11/06/om2-opinions/

https://www.filmshooterscollective.com/analog-film-photography-blog/olympus-om-user-review-4-29

Really interesting. I bought an Olympus OM-1n in the very early 1980s and loved it. I still have it displayed in a place of honor in my living room and still love it. Great glass. The compact size and light weight was a sensation at the time and one of the big selling points to me. I always found it simple and intuitive to use. A great camera. The Olympus company history was really good. i didn’t know that much about how the company started. Great work on the article. Jeff Oliveira in CA

Fantastic write-up, and one that I find a lot of relation to. Having an OM-2n, I find myself not liking it as much as I feel I should, and I think a lot of this has to do with the shutter speeds on the collar ring, which only seems to deter its use and persuade the user to rely more on the Auto mode since it is somewhat easier to use. Aside from that, it’s a great size camera with a large bright viewfinder that does manage to stand out a bit from the typical 70’s SLR cameras.

Your mention of two separate meters though has given me a lot of pause for thought. Mine tends to indicate somewhat “optimistic” shutter speeds about a stop faster than expected. I would wonder if the separate OTF meter (provided it is accurate) would essentially negate the somewhat off CDS settings when the camera is in Aperture priority mode since the two systems are presumably uncoupled. It would only be when in manual mode that following the CDS meter’s recommendation would run you afoul?!?

Adam, you are definitely onto something. The CdS meters (there’s actually two of them according to page 98 of the OM-2’s user manual) likely do return a reading different than what the SBC meters do at the film plane. In auto mode, this could show a reading that is different than what the camera would actually use. This could mean that the SBC meters are right and the CdS meters are wrong or vice versa.

It also has the side effect that if the CdS meters are faulty, in full manual mode, you could choose a shutter and aperture combination that’s incorrect if you depend on the reading of the match needle.

Also interesting is that according to the user manual, the EV sensitivity is different between the two sets of meters (SBC: EV -6.5 to 18, CdS: EV 1.5 – 17)

I totally get why Olympus needs two sets of meters as there’s no way a film plane meter would work with the mirror down, but it hints at a camera that could behave completely different in Auto mode compared to Manual mode.

So, an idea just occurred to me.

Sans film, I should take my OM-2 out in dark conditions and find a setting where the external meter reads 1/2 or 1 second (on my presumption of it over-exposing) in Auto mode and fire the shutter and see if the actual duration is longer!

My first SLR was an Olympus back in the eighties so I have fond memories of it. You do get used to the shutter ring, you can leave your finger on the shutter button and adjust both aperture and shutter speed with your left hand. I think you may have the shutter speed and curtain arrangement the wrong way around, at 1/60 and slower the silicon cells read off the film, at higher speeds it’s a mixture of film and curtain pattern, faster the spees the more it is of the curtain.

Excellent review, I love the OMs, still my everyday camera

If you fire the Om-2 without film in Auto mode, the shutter speed will be much SLOWER than indicated in the viewfinder by the CDS cells. This is because the camera will be measuring the light off of the black (dark) pressure plate. The two meter readings need either film or the originally supplied film plane greycard installed if the two readings are to be reasonably close.

The article completely leaves out the main benefit of the OM-2 metering system which is for flash — it was the first camera commercially manufactured to use TTL flash with selected Olympus flashes, that is so widely used today, allowing greater freedom to pick apertures with flash, as well as accurate bounce flash and multi flash setups automatically. This was revolutionary.

As to the shutter speed ring around the lens mount, once one gets used to the location, it is superior to the standard setup as one hand can focus and adjust aperture and shutter speed with one’s finger always on the shutter release. I also use film Nikons like F2as, FE2 and FM3a — and don’t like having to change my grip and take my finger off the shutter release to change the shutter speed. Once you use the OM-2 for a few days, you’ll agree.

Dean, I have definitely warmed to the arrangement of the shutter speed location, but I still don’t love it. Since publishing this review, I’ve acquired an OM-4 that I’ve shot a number of times and will eventually review. I completely understand why the location of the ring is there, but unless it’s a camera you consistently use day in and day out, it’s hard to switch between so many different cameras like I do when reviewing, and then having to readjust my muscle memory with the Olympus cameras. Make no mistake, I’m a huge fan of the entire OM-series and my experience with both the OM-2 and OM-4 are very positive otherwise!

You say that “..it is said that Yoshihisa was inspired by the Leica M-series rangefinder in designing the M1 as the goal was to have the camera be no larger or heavier than the Leica..” and your caption beneath the picture of the Leica M3 and the OM2 says “..You wouldn’t know it from looking at them, but the Leica M-series was the inspiration for the size and dimensions of the Olympus OM series.” No; sorry.

The reason that “You wouldn’t know it from looking at them” is that the OM2’s size was not based on the Leica M series, but on the earlier, smaller, original, ‘Barnack-style’ Leicas.

If you ignore the pentaprism on the top of the OM2 (which, in any case, is sunk deeper into the body than other SLR manufacturers put theirs) and you ignore the projecting lens mount, which sticks out from the body, then the body of the OM2 (and the OM1 before it) is the exact same height, width and depth as a Barnack-style Leica, which Mr Maitani, the designer of the OM series, owned when a young man ..the versions which were made before the bulkier, heavier M series Leicas.

What an insightful article. I have been wanting to purchase an Olympia OM-1 for some time. Once again, I placed a bid on eBay and lost by one dollar. I check a local online marketplace application on my phone and found a listing for several cameras including the elusive OM-1. Once again, the OM-1 sold before I can get to it. However, the seller did have an OM-2 which I was not too familiar with. I did not realize the camera was so small. We met in at the local In N Out parking lot. Here I successfully tested out the camera. I decided to purchase it with a third party lens.

The one thing that I do not like is the lack of adapters. It is easy to find a Olympus OM to (name the camera) adapter, but next to impossible, or even impossible to use my other non-OM lenses on this camera.

Once again, I went to my local marketplace to look for another lens. This time I found a listing for 3 OM-2n cameras for $99 untested. I decided to roll the dice and buy the cameras.

Once I got home, I placed the cameras on my table and took out six LR44 batteries. The first camera worked, the second camera worked, the third one functions, but constantly needs to be reset. Oddly, I still have one lens for four cameras. I am going to start testing with a roll of Fomopan 200. The metering and electronics seem to be working, but a fresh roll of film will be required to fully test it.

I am traveling later this week so will likely not travel with the camera until I feel that I have fully vetted it. In the meantime, I will either take my trusted Canon AE-1 Program or Contax (one of a few).