This is a Pentacon Super, a 35mm SLR made by Kombinat VEB Pentacon Dresden between the years 1968 and 1972. The Pentacon Super was the sole attempt by Pentacon to build a professional level SLR. It had a number of features such as an interchangeable metered prism, open aperture metering, a hybrid cloth and metal vertically traveling focal plane shutter with top 1/2000 shutter speed, a full information viewfinder, and external motor drive coupling. The camera used the standard M42 screw mount, but in order to support the camera’s open aperture meter, special lenses with an internal coupling pin were developed for this camera. Lenses without this pin could still be used, but only with stop down metering. The camera was very heavy and expensive, but compared to more advanced cameras that had already been on sale outside of Germany for a lot less money, the Pentacon Super sold poorly and is very rare today.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 50mm f/1.8 Carl Zeiss Jena coated 6-elements in 4-groups

Lens Mount: M42 Screw Mount (Open Aperture Metering Requires 2 Pin M42 Lenses)

Focus: 1.2 feet / 0.35 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Interchangeable SLR Pentaprism

Shutter: Hybrid Vertically Traveling Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 10 – 1/2000 seconds

Exposure Meter: TTL Coupled CdS Cell w/ Viewfinder Match Needle

Battery: 1.35v PX625 Mercury Battery

Flash Mount: PC Sync Port, FP, F, and X Sync, 1/125 X-Sync

Other Features: Self-Timer, Shutter Lock. Interchangeable Focus Screens, DOF Preview (On Lens), Battery Check

Weight: 1096 grams, 900 grams (body only)

Manual (in German): https://mikeeckman.com/media/PentaconSuperManual.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Pentacon Super was the most ambitious 35mm camera Pentacon ever made, with features that should have put it near the top of the pro 35mm SLR echelon, and on paper, they succeeded, however in reality the camera was extremely expensive and coming from a company not known for pro-level gear, sold poorly outside of East Germany. The Pentacon Super is a good camera, with a long list of features, but it simply doesn’t compare to other cameras from the same era in which it was made. As a collector’s item, this is a cool camera to have, but its rarity and price today, plus with many not found in working condition today, make this a difficult camera to recommend to someone actually wanting to use it. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 20% | |

| Bonus | None | ||||||

| Final Score | 10.8 | ||||||

History

The state of the East German postwar camera industry was a mess. Starting with the total devastation leveled by Allied forces during World War II, what factories survived were very old and ill equipped to compete with the rapid modernization of the camera industry innovated by both Japanese and West German companies. Further complicating matters in East Germany was that the company that had one of the best reputations outside of the country, Ihagee, was partially owned by a Dutchman, and due to the East German government’s desire to maintain friendly trade partnerships with The Netherlands, Ihagee could not be nationalized into a government sanctioned entity.

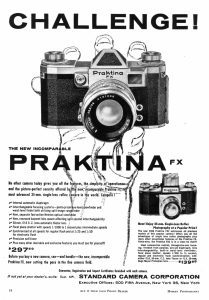

As a result, the companies that did survive the war, largely produced mid to lower end cameras. Simple scale focus and rangefinder models by Certo and Balda were common, as were basic SLRs like the Praktica. For the pros, if you didn’t want an Ihagee Exakta, the only other good option was the KW Praktina from 1952, which actually was a pretty decent camera, but it was an overly complicated camera that cost a lot to make and even more to sell. KW Praktinas were outside of the spending range of all but the most wealthy photographers, and a lack of brand recognition outside of East Germany meant the camera didn’t sell well in export markets.

KW would be merged in with Zeiss-Ikon and a few other German camera factories in 1959 to become VEB Kamera-und Kinowerke at which time a consolidation of models began. The Praktina wasn’t initially on the chopping block, but a 1960 price cut didn’t do much to boost sales, as only a couple months later, in May 1960, the Prakinta was discontinued.

The timing for the discontinuation of the KW Praktina couldn’t have been worse as it was right around the time pro-level SLRs from Japan would hit the export market. Models by Nippon Kogaku and Canon were released in May 1959 with exporting to Europe and North America in early 1960. Furthermore, mid-level and advanced amateur models by Minolta, Konica, Yashica, and a variety of other companies also flooded the market. With only the aging Exakta to sell, the East German camera industry was without a feature rich SLR to sell to anybody.

In an effort to reverse this trend, in 1961 work began on a new shutter that could achieve faster shutter speeds while also being quieter. By 1963 a prototype camera, called the Praktina N was reportedly made whcih showed an all new camera that featured the new 1961 shutter. A TTL metering system developed by Horst Strehle reportedly was part of the Praktina-N’s specifications. No examples of the Praktina-N have ever been found, but a wooden mockup created by Manfred Claus is pictured to the left.

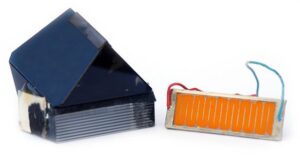

A notable design element of both the Praktina-N and final Pentacon Super is the huge metered prism. The reason for the large size had to do with an all new TTL metering system that is integrated inside the prism. Designed by Horst Strehle, the meter used two wedged pieces of glass that act sort of like a beamsplitter. When light would pass through the wedge, a portion of the light would be reflected to a long light sensitive resistor and the rest through the prism into the viewfinder. This system, although advanced for its era, proved to be less effective than simpler TTL CdS meters which were soon deployed in other Praktica models like the Praktica Super TL.

Development of a new SLR continued but by the 1966 Leipzig Spring fair, the Praktina-N was dropped and the camera was given the name Pentacon Super. The camera made its debut showing a body not entirely unlike the Praktina-N wooden model, but with a M42 lens mount, open aperture metering, a new vertically traveling hybrid shutter with top 1/2000 shutter speed, and an all new body design. To support the feature of open aperture metering using a screw lens mount, the designers of the camera made special lenses with a secondary pin which moved a feeling ring around the perimeter of the lens mount forward and backward, depending on which f/stop was selected. This effectively allowed the lens to communicate back to the in-body meter how much light would be let through the diaphragm at the moment of exposure, without having to stop it down first, like on every other metered M42 SLR. According to brochures for the camera at the time of its release, a total of 10 lenses ranging from 20mm to 300mm would support the second pin for the Pentacon Super, but it is not certain if all 10 were ever made.

The camera was a technological tour de force, at least as far as an East German SLR was concerned. Many of the Pentacon Super’s features matched up to those already available on other Japanese cameras like the Topcon RE Super and Nikon F, but it was a first for a Pentacon produced model.

For reasons I was unable to discover while researching this article, it would be another two years after the Leipzig announcement and when the camera first became available in October 1968. In those two years, the camera saw many minor cosmetic changes, such as a smaller logo, a change in body covering, and cosmetic differences on the bottom plate, strap lugs, and various knobs on the camera.

vPerhaps an unappreciated characteristic of the Pentacon Super was that many of the camera’s internal components were built as separate modules and assembled together to make a finished camera. The entire shutter, reflex mirror, metering system, and film transport were made separately and assembled together, helping to minimize labor in the assembly process. This also, in theory, should have meant the Pentacon Super would be easier to repair. If the metering system or the shutter needed work, each system could be separated completely from the rest of the camera, repaired, and then put back in.

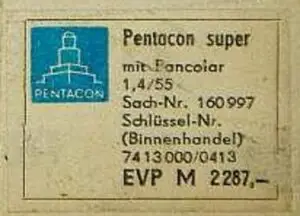

Despite any potential cost saving this might have resulted in, at the time of its release, the Pentacon Super still ended up being extremely expensive. When sold with a 55mm f/1.4 Zeiss Pancolar lens, the camera carried a retail price of 2287,- Mark, the motor drive was 547,- Mark, the 17 meter bulk film back was 320,- Mark, optional waist level finder was 87,- Mark, and leather case was 45,50 Mark.

According to the inflation calculator at lawyerdb.de, when adjusted for inflation, the cost of just the camera and 55/1.4 lens compares to 5170 Euro today. Using Google’s currency convertor, this compares to just under $5600 USD today an absolutely astounding price for a camera. If you were to package out the camera with motor drive, bulk back, multiple viewfinders, and a selection of lenses, the prices could skyrocket further.

In a surprise to no one, the Pentacon Super sold poorly. It is not clear if any attempt was made to export it out of the country, but I would find that to be very unlikely as any non-German country who might be interested in a top level SLR, probably already had access to Japanese cameras which had the same, or similar features, more proven reliability, and cost significantly less. Less than an estimated 4500 units were produced before the camera’s production was halted in January 1972.

Perhaps due to the failure of the Pentacon Super and the East German camera industry’s continued failure to market a high end 35mm SLR outside of Germany, VEB Pentacon would never again attempt another camera like the Pentacon Super. Production of entry to mid-level Prakticas continued through the 1990s, with those models eventually featuring things like electronic shutters, automatic exposure, and even an all new Praktica-specific bayonet lens mount.

Today, collectors often dismiss most East German SLRs out of misguided snobbery. Many Praktica models are quite good cameras that are reliable and often feature excellent lenses. The Pentacon Super however is relatively unknown. It is possible that some have mistaken it for “just another Praktica” which it clearly is not, but even if one was aware of this model’s existence, its rarity, combined with astronomical asking prices on the used market keep them away from all but the most deep pocketed collectors.

My Thoughts

One time on some random forum, blog post, or Facebook group, I heard someone say “If you’ve seen one Praktica, you’ve seen them all…” As a fan of many different Prakticas, I both agree and disagree with that statement. On the agree side, there certainly were a LOT of Prakticas that all had very similar features. When a new Praktica model would come out, often very little had changed from the model before it. When you look at the huge number of different models on sites like Mike’s Praktica Collection, you can’t help but notice there wasn’t a lot of variety.

However, if you look hard enough, you’ll see interesting models like the Praktica IV and V models with their bottom wind film advances and large and bulbous prisms up top, and the later VLC 3 with its removable prism and electronic lens connection.

One thing you’ll never find however, is a professional level Praktica, at least not anything that aimed to compete with the likes of the Nikon F and Canon F-1. If you dig hard enough into the history of the East German camera industry, you’ll find one single model. Made by VEB Pentacon, the same company that absorbed KW the original maker of the Praktica (and Praktiflex), the Pentacon Super is the closest you’ll ever come to a “Pro Praktica”. Why the camera isn’t called a Praktica is a mystery, but if I had to guess, it was probably an attempt to differentiate between the company’s consumer line, much like how Nippon Kogaku called its first consumer level SLR a Nikkormat, instead of a Nikon.

At a quick glance from maybe 10 or more feet away, the Pentacon Super looks sorta like a larger Praktica. It has a similar film advance lever, most of the lenses have those alternating chrome and black zebra stripes on them, and the center of the pentaprism has the familiar Ernemann Tower. Beyond that though, the cameras are different, VERY different!

Starting with the size, the Pentacon Super isn’t just a little bigger, it is a LOT bigger. Compared to other large 1960s SLRs like the Nikon F w/ Photomic prism and Tokyo Kogaku Topcon R, the Pentacon is larger in every dimension. The difference is almost comical when placed next to more compact SLRs like an Asahi Pentax Sv or an Olympus OM-1. At a weight of 900 grams body only, the East German behemoth is the heaviest 35mm SLR I have in my collection, it even outweighs some lighter TLRs like the Yashica D and Minolta Autocord. This is a mighty camera that requires large and strong hands. For long shooting sessions, a wide and padded neck strap would be a must to avoid fatigue.

Up top, things start off inconspicuously with a pretty normal rewind knob with fold out handle on the left. The knob lifts up to make inserting and removing the film cassette earlier, but is not used to unlock the film door. Unlike many other cameras of the era, there are no other controls beneath or around the rewind knob.

Next to the rewind knob, taking up roughly a third of the entire width of the top of the camera is the gargantuan removable pentaprism. Although massive, if I’m being fair, it is not any less bulbous than a Nikon F Photomic prism. In addition to CdS exposure meter and associated electronic circuitry, a large round door unscrews to reveal the battery compartment where a single 1.35v PX625 mercury (or equivalent) battery goes. Around the battery compartment is a separate ring with a black dot that points to a green, red, and yellow dot on the side of the prism. With the black dot lined up to the red dot, the meter is off, the green dot means it is on, and the yellow dot is a battery check position in which the meter needle visible in the viewfinder will always move to the middle position regardless of light. In front of the battery compartment is a trapezoid shape window which I’ll explain later.

To the right of the prism is the film advance lever with combined film type reminder dial, shutter speed selector, and film speed selector. Starting with the advance lever, it is a quick wind design that starts with an approximate 15 degree offset. Beyond that, another 180 degrees is required to fully wind the film, tension the shutter, and advance the exposure counter. The lever must be moved in one single motion as multiple smaller motions are not allowed. The film type reminder dial is just a knob on top of the wind lever and has 4 icons for various types of color film and one for black and white. Strangely, if you turn this dial too much, it will completely unscrew from the camera, so don’t do that.

The selected shutter speed is shown through a rectangular opening pointing towards that trapezoid window on the side of the prism. This window is connected to a lens inside of the viewfinder, allowing you to see your selected shutter speed while the camera is to your eye. Shutter speeds from 1 – 2000 second plus Bulb can be chosen here. Shutter speeds 1 to 15 are indicated in red to caution you to stabilize the camera. A lightning bolt at the 125 setting indicates the X-Sync speed. The Pentacon Super supports longer shutter speeds down to 10 seconds, but these are accessed using the self timer, similar to an Exakta. I’ll get to that later. Finally, the film speed selector shows ASA and DIN speeds from 6 to 3200 and 9 to 33. Changing the film speed is a bit odd as the index mark is visible next to the 1/60th shutter speed. The easiest way I can explain it is to set the shutter speed to 60 first, then lift up on the outer ring and rotate until your desired film speed is next to the index mark next to the number 60. Once you have a film speed set, you can change the shutter speeds back to whatever you want.

Flip the camera over and on the bottom we see a 1/4″ tripod socket beneath the mirror box which is the center of weight for the entire camera, ensuring proper balance with the camera on a tripod. Off to one side is the motor drive coupling which connects to a special battery powered unit made specifically for this camera. To the right of the coupling is a deeply recessed rewind mode switch. Above and to the right of the rewind switch is an electromagnet contact point which is used by the motor drive to communicate back with the camera.

On the other side of the base of the camera is the combined self-timer and slow shutter speed knob. The Pentacon Super uses a slow speed escapement that controls both the self-timer, shutter speeds from 2 to 10 seconds, and a combination of self timer and between 2 to 6 seconds. The basic functionality is very similar to what Ihagee designed with the Exakta’s combined slow speed and self-timer mechanism. I am unsure if the internal mechanism is the same, or just functionally similar. That Ihagee Kamera-Werk AG eventually was merged into VEB Pentacon and Pentacon would produce their own version of the Exakta using a similar design at least suggests that there was some shared technology.

Note 1: The Pentacon Super is a rare camera and is also over half a century old. Many examples of these cameras do not work properly. As with any mechanical camera, the self-timer and slow shutter speeds are the most likely to not work. Using the self-timer on a camera that has not been serviced can jam up the shutter and cause permanent damage. The owner of this camera told me it was recently serviced, so I felt comfortable playing with these settings, but if you come across one and aren’t sure of its operational condition, I strongly advise not trying to use this part of the camera.

Note 2: I used a combination of Google Translate and the German manual for the Pentacon Super to fully understand how this part of the camera works. One thing the manual does not say is whether the shutter needs to be tensioned before trying these settings. I found that while using them, the camera cooperated more with the shutter tensioned first. Perhaps when new this wasn’t a concern, but even with this camera being serviced, I found that it worked better to play with the self-timer and slow speeds with the shutter always tensioned first.

To use the slow speeds and self-timer, you first must understand that there are two pieces, a fold out key that winds up the escapement and an outer ring with zebra stripes and numbers from 2 to 10 in green, 2 to 6 in white, and the letter V in white. Regardless of what you want to do, the first step is to always wind up the mechanism as far as it will go by folding out the half circle handle of the key and turning it back and forth several times until it will not move any farther. The key does not turn in a complete 360 degree circle and will only move about a quarter turn. A complete wind takes about four and a half quarter turns. You must always fully tension the mechanism regardless of which slow shutter speed you are using or whether you want to use the self-timer or not.

Once the mechanism is fully wound up, the next step depends on what you want to do. If you are only using the self-timer, you can set the main shutter speed dial to any fast setting you want. For example, if you want to use the self-timer and a 1/125 shutter speed, set the main shutter speed dial to 125 and turn the zebra ring to the letter “V”. When you press the shutter release, the escapement will begin winding down, and after about 12 seconds, the shutter will fire at 1/125.

If you want to use a slow shutter speed from 2 to 10 seconds, you must first set the main shutter speed dial to B. If the main shutter dial is at any other speed, the mechanism will not work correctly. With the camera set to B, the shutter tensioned, and the escapement fully wound up, turn the zebra ring to one of the green numbers 2 through 10. These correspond to how many seconds long you want your exposure to be. Press the shutter release and the shutter will immediately open and the escapement will count down and after how many seconds you chose, the shutter will close.

If you wish to use the self-timer and a slow shutter speed from 2 to 6 seconds, set the main shutter speed dial to B, tension the shutter, wind the escapement all the way and turn the zebra dial to one of the white numbers. Press the shutter release and after an approximate 12 second delay, the shutter will open for however many seconds you chose.

If this sounds confusing, I have made a video showing the operation of the camera in all three modes.

The sides of the camera are mostly symmetrical. The left side has the sliding lock for the door latch and both sides have forward angled metal strap lugs. To have a camera this heavy without strap lugs would almost be a crime, so it is very good that they are here. That they are forward angled helps prevent the camera from tipping forward with a heavy lens and the camera dangling from your neck.

With the right hinged door open, the film compartment looks like most other East German SLRs. Film transports from left to right onto a fixed and single slotted take up spool. Film winds onto the spool opposite the direction the film rolls up in the cassette. This is done to help promote film flatness as it transports through the camera. Inside the film door is a large black painted metal film pressure plate covered in tiny divots to reduce friction as film passes over it. A metal clip near the door latch is there to hold the film cassette still. The door is removable via a small sliding latch on the hinge for attaching an optional 17 meter film bulk back. Inside the upper and lower door channels and inside the door hinge are fabric light seals, which on this camera were still in good condition and did not need replacement, although like any old camera, should be inspected to make sure no light can leak onto your film.

Looking down upon the top of the Zeiss Pancolar f/1.8 lens, the aperture ring is closest to the body with click stops from as small as f/22 to f/1.8. In front of it is a fixed depth of field scale with an IR focus mark between f/4 and f/8. Finally is the focus ring with distances measured from 1.2 feet and 0.33 meters to infinity. Both the focus and aperture rings have an alternating metal zebra pattern which was popular for German lenses of this era. I much prefer the feel of all metal lenses rather than the rubber coatings used on lenses later which can crack, get sticky, or fall off altogether.

Up front, the camera shows its Praktica roots with a 45 degree angled shutter release. The shutter release is comfortably located and within easy reach of your right index finger while shooting. The button is threaded for a cable release and has a rotating shutter lock to prevent accidental presses of the shutter. Next, in the bottom left corner is the exposure counter. The counter is additive, showing how many exposures have been on the current roll and automatically resets when the film door is opened. This is a rather unusual location for an exposure counter as its location means the photographer has to completely remove the camera from their eye and rotate the camera to look at the front. At the very least, it does look kinda cool. On the opposite corner is the PC flash sync port for connecting to a flashgun. A switch on the side of the mirror box has three positions for FP, F, and X sync. Unlike other pro-level SLRs with removable prisms, there is no hot shoe connection under the rewind knob, or hidden elsewhere on the camera. Looking at the German language manual, the only flash connection is the PC port on the front.

The Pentacon Super uses the M42 screw lens mount like the Praktica. It supports the same lenses with or without automatic diaphragms like pretty much every other M42 camera from the same era, however the Pentacon Super has an additional feature that most M42 cameras do not, which is the ability to meter with the lens wide open. Most other M42 lenses with meters require you to stop down the lens first, before the meter can measure the exact amount of light coming through the lens.

To accomplish this feat, lenses designed specifically for the Pentacon Super have a second pin in the lens which presses against a curved metal lever around the perimeter of the lens mount. As you turn the aperture ring on these lenses, the pin mechanically extends or retracts back in the lens. Wide open, the pin is retracted, when stopped down to the smallest aperture, the pin sticks out, pushing in on this lever around the lens mount, telling the meter which f/stop you’ve selected. This system actually works quite well and it is a shame that more M42 mount cameras didn’t employ a similar feature as it would have made future metered and AE SLRs much more flexible.

The Pentacon Super was targeted at professional photographers and like most other pro-level SLRs, it has an interchangeable viewfinder and interchangeable focus screens. Removing the prism is very easy and is done by pressing in on two round buttons on opposite sides of the eyepiece while lifting up on the prism. Reinstalling the prism is the opposite of removal.

With no finder installed, you can use the camera at waist level, however there will be glare without a hood. The focus screen can be swapped out with one of 4 different kinds mentioned in the user’s manual. I am unsure of more were developed after the camera’s release. Strangely, with the prism removed from the camera, the meter needle is still visible in the body of the camera, but it is useless without the prism as that is where both the metering cell and power supply is located. With the prism installed, power is supplied back to the body to move the needle using electrical contacts.

The Pentacon Super has a full information viewfinder, showing selected shutter speed, f/stops, the meter readout, and a shutter readiness indicator. How all of this is accomplished is wonderfully German and complicated, however. Starting with the shutter readiness indicator which works exactly the same as those from Prakticas of the same era in which a triangle pointer protrudes into the visible area when the shutter is not tensioned. Move the film advance lever and the pointer disappears.

Both the shutter speed and f/stops are displayed using separate “Judas windows” above the viewing screen. The aperture is shown inside a long oval window by pointing a lens at the physical aperture ring of the lens. Although a similar system is used by many other camera makers including Nikon and Minolta, the problem with the Pentacon Super is that the location of the aperture ring on the lens changes depending on which lens you have. I have a period correct “two-pin” ausJena 180mm f/2.8 lens in which you can’t see the aperture ring at all through this window. Even with the Zeiss Pancolar 50mm f/1.8 lens, the ring is nice properly centered in the window, but it does work. For shutter speeds, another window on the side of the pentaprism looks at the shutter speed dial on the top plate of the camera. While this window does work fairly well, I found it difficult to see both the selected shutter speed and f/stop at the same time. Furthermore, since both windows rely on ambient light hitting the top of the camera, you can’t see either in poor lighting.

On the right side of the focus screen is the meter readout, which is a traditional match needle system. Inside the area where the needle points is tinted yellow, inside of a thick black frame which blocks a good amount of the right side of the viewfinder screen. A horizontal line in the center of the match needle display is both the “correct” meter position, but also the position where the needle should move when the battery check function is used on the prism.

The viewing screen on the camera I have, has a traditional split image focusing rangefinder in the center, but around its perimeter is a strange Fresnel collar that sorta acts like a split image in that it distorts the image in a spherical shape. It is difficult to explain, but it does not look like any other ground glass collar or Fresnel screen I’ve ever seen. Around this “focusing Fresnel collar” is a more traditional Fresnel screen that just blurs the image when focus is incorrect. The purpose of the Fresnel rings is to maintain even brightness across the screen from corner to corner. Even with these rings however, I found the Pentacon Super’s viewfinder to be unacceptably dim for a professional level camera sold between 1968 to 1972. Had this camera been made in the 1950s, it would have been on par, but if VEB Pentacon had ever hoped to export this camera and compete with models from Japan, the viewfinder was entirely too dark. Even with the dark viewfinder, that the company was able to implement a meter read out, two Judas windows, a shutter readiness indicator, along with both interchangeable finders and focus screens, is quite remarkable.

The Pentacon Super has a lot of things going for it. Back to the statement I started this section off with, if you think you’ve seen every Praktica out there, you definitely haven’t seen a Pentacon Super, which I guess is a good reason not to give this the Praktica name. Regardless of your feeling about the name, it is clear that the designers who built their camera did their best. Their implementation of open aperture metering was quite good, I applauded their efforts in making a full information finder even if it doesn’t work in every scenario, and that the camera has pro-level features like changeable viewfinders and a motor drive coupling means they were paying attention to what the pros used.

The Pentacon Super is a cool camera and is very hard to find in working order, but with one in my hands that does work, I only thing left to do is shoot it…which is exactly what I did! If you want to hear how that turned out, keep reading!

My Results

This camera came to me as a loaner from site reader Jeff Felton who had this example CLAd recently. Jeff contacted me and said he was interested in loading me the camera to give a review of as he was aware of how rare they were and wanted to see what I could come up with. Of course, any time someone offers to send me a camera that’s both rare and perfectly working, I gladly accepted!

I had intended to shoot a couple rolls of film through the Pentacon Super, but I would only end up shooting one roll of fresh Fuji 200. I had every intention of trying another roll, but projects kept piling up and feeling pretty confident that the results of the camera, although a top tier model, would mimic that of other M42 screw mount cameras, I stuck with the inaugural roll.

It is probably not fair to compare the Pentacon Super to any Praktica made by VEB Pentacon as the two cameras don’t share the same name, but also because the Pentacon Super was intended for an entirely different market, but it is very difficult to so much as look at the Pentacon Super and not see it as some type of beefed up Praktica.

Regardless of how your mind reconciles such a camera, the similarities between this camera and the “lesser” Prakticas are much greater than what’s different. Shooting this camera compared to a period correct Praktica is much like comparing a Nikon F2 to a Nikkormat. Both cameras are made by the same company, look vaguely similar, use the same lenses, work mostly the same way, but were built for a different audience.

In the case of this particular Pentacon Super, I shot it with a Carl Zeiss Jena Pancolar 50mm f/1.8 lens, which is much like ones that would have been found on many Prakticas, so when it comes to image quality, it is exactly the same. The Pancolar 50/1.8 was an evolution of the Pancolar 50/2 which itself evolved from the Flexon 50/2 which evolved from the Biotar 50/2, so there are a lot of other lenses out there that will perform the same as this one.

Image quality on this lens was quite good, at least as comparable to most 50/1.8 lenses of the same era. In an online database of reviews for the Pancolar 50/1.8, it is said that although many of these lenses are good, there is a wide range of sample variation in terms of quality, so like with pretty much any interchangeable lens camera, your results will vary based on which exact lens you use.

As for the camera, the Pentacon Super is big…super big like its name suggests. At a weight of 1096 grams with the lens, you’ll never forget you’re carrying the it around while out shooting. Thankfully, the Pentacon Super is still within my comfort zone for large SLRs, and I didn’t have any specific issues with the canera’s heft or ergonomics, but I suspect those with smaller hands might take issue with the camera’s bulbous dimensions. The front angled shutter release was comfortably located and required just the right amount of force to actuate, although doing so results in a loud cacophony of sounds coming from the vertically traveling half metal/half cloth shutter. If you describe the camera as “super sized”, you also need to describe it as “super loud”.

Changing shutter speeds wasn’t an issue, although the location of the index mark is in a strange forward facing position. The judas window in the viewfinder allows you to see your selected shutter speed with the camera to your eye, but like all judas windows, it requires both sufficient outdoor light and your eye to be in just the right location to be able to see through the window. Position your eye a fraction of a degree off in any direction and what comes through the window becomes distorted and difficult to read. While not impossible to see while wearing prescription glasses, its not perfect.

The viewfinder tells you everything you need to know about exposure and is probably the best I’ve seen from an East German VEB Pentacon 35mm SLR, but it still lags behind what the both the Japanese and West German companies like Leitz were doing at the same time. The viewfinder is dark, comparable to a 1950s Minolta or a Soviet Zenit. I suspect there are many reasons the Pentacon Super wasn’t successful in western markets, but in that list would definitely be the darkness of the viewfinder.

Despite these challenges, I hesitate to say that using the Pentacon Super was a miserable experience. I certainly have seen worse, but for a pro-level SLR that was still being sold in the 1970s, it simply does not compare. I had no issue operating the camera, or getting good images from it. Amazingly, the exposure meter on this example not only worked but was accurate, but I found the design of the yellow tinted match needle to be unnecessarily murky. Like the rest of the viewfinder, it wasn’t bad, just not the best.

It is clear that whoever was responsible for the overall design of the camera had high ambitions, but its shortcomings were certainly the result of a lack of resources in East Germany at the time it was made. Had this camera been made with the expertise of what the Japanese had at the time, it likely would have been a much improved camera.

The Pentacon Super is not a bad camera and I enjoyed my time shooting it, but I can very much see why the camera was not successful. If all you wanted was to get good images from a metered SLR, you are much better off finding a Praktica or even a Soviet SLR from the same era. Not only will that camera be simpler and less likely to fail, but will also cost you significantly less. The Pentacon Super not only carried an extremely high retail price when it was first sold, but examples of this camera today are still out of reach of most people. I’ve seen examples of this camera with the Pancolar 1.4 lens on sale for $2000 and up, which in my opinion is unreasonable. Adding one of these cameras to your collection should be reserved only for the deepest pocketed collectors. For anyone actually wanting to shoot one, you can get 90% of the experience with a Praktica at 10% of the cost.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Pentacon_Super

https://zeissikonveb.de/start/kameras/pentacon-super.html

http://www.praktica-collector.de/119_Pentacon_Super.htm

Great review Mike. I have a Super with the motor drive (useless, unless you have the battery & connecting cords), but still cool. I have an earlier thorium glass Carl Zeiss Jena Pancolar 50/1.8 mounted, as the legendary F1.4 is also legendary in price. It is a beast but I’m all about big heavy cameras, owning a couple Contarex’s, an F2, Topcon SuperDm, and a Minolta XK. Just call it a “workout” dragging these around with any kind of fast glass lens mounted.

I believe your review is spot on and you covered this camera from top to bottom. If it had any redeeming feature it might be there weren’t many SLR’s at that time with 1/2000 sec shutter and a 1/125 sec Flash synch.

“The Pancolar 50/1.8 was an evolution of the Pancolar 50/2 which itself evolved from the Flexon 50/2 which evolved from the Biotar 50/2”

As far as I understand it, the Flexon and Pancolar 50/2 are the same, just renamed, and the Biotar is a 58/2. I have the Biotar 58/2 and the Pancolar 50/2, together with a Tessar 50/2.8, for Praktina…

In the article I linked to from zeissikonveb.de in my article, it says in the Summer of 1955, 100 copies of a Biotar 50/2 were produced as prototypes. A month later, another 1000 were ordered, but the name changed to Flexon. So while the only Biotar you’re likely to ever see is the original 58/2, there was at one time, going to be a Biotar 50/2.

I had read this article 1-2 years ago and had forgotten the details, so you are right, there was a very small batch of Biotar 50/2. But it also mentions that the Biotar 50/2, the Flexon 50/2 and the first iteration (1954) of the Pancolar 50/2 are the same, just renamed, and the Pancolar 50/2 was reworked in 1960 (section 3 & 4 of the article). So, if these three were the same, I wouldn’t call it an evolution of each other…