In my last lens review for the Schneider-Kreuznach Tele-Xenar 135mm f/3.5 in April 2021, I mention that I do not try, nor do I want, to review lenses. However, in this hobby, sometimes a lens shows up in a box, or in the deep bowels of the online marketplace that is so interesting or unique, that I have no choice but to take a deeper look at. Such is the case of the Sankyo Kohki Komura 500mm f/7.

I found this lens at a local shop who often consigns stuff from estate sales through their website, and they often have a good selection of cameras and photographic equipment. Their prices are usually high however, so I rarely find stuff there that I’m willing to pick up. The store requires you to buy the product online, and then they’ll either ship it to you, or you can arrange to meet them to pick up your purchase, so inspecting a potential purchase in advance is not an option.

The reason this is significant, is that this lens was described as “Lens Parts”. The people who run the store know just enough about cameras and lenses to properly identify what they’re selling, but they rarely know how to use it. This Komura lens is so large that it breaks down into separate parts and is often found in it’s own velvet lined case. This clearly threw off the shop as they didn’t realize you had to assemble the lens for it to work. Willing to take a gamble that these “Lens Parts” were really a single lens that just needed to be put together, I threw out an offer, which they agreed to so I arranged to pick it up.

Komura is the brand name of a family of lenses made in Japan by Sankyo Kohki starting in the early 1950s. Very little is known about the origins of the company, or if they had any dealings with other products or industries before or during the war, but as the Japanese optics industry started to gain momentum after the war, a large variety of third party lens makers started to appear.

Sankyo Kohki’s earliest products were lenses sold under the name Chibanon or Chivanon. Many lenses were made for enlargers and a variety of early Japanese folding cameras. Camera-wiki suggests that Sankyo Kohki lenses were produced for Tōsei Kōki but I have found no such examples.

As the company grew, it’s lens offerings expanded to interchangeable lens rangefinders and SLRs. Komura lenses made in the Leica Thread Mount and Nikon rangefinder mount were the most common. At the time, German built cameras like the Leica and Contax were still very much in favor, but with exposure by respected photographers like David Douglas Duncan who primarily shot Nippon Kogaku Nikkor lenses, brought a great deal of awareness to Japanese lenses that Sankyo Kohki almost certainly benefitted from.

By 1960, Sankyo Kohki was one of the biggest third party lens makers in Japan, their wide angle and medium telephoto lenses were very popular as they offered excellent image quality at a price less than more established German and Japanese brands. This apparently drew the interest of western photographers and American distributors like Joseph Ehrenreich. This led to a US trademark filing in December 1962 for the company, now known as Sankyo Koki Co., Ltd.

I do not have a complete history of all Komura lenses, or in which order they were released, but as one of the world’s biggest third party lens makers, Sankyo Kohki certainly wanted to appeal to photographers no matter what camera they shot. In addition to lenses made for Leica and Nikon rangefinders, versions of Komura lenses were made with adapters for the M42 “Universal” thread mount, Exakta, Nikon F, and many others.

The best glimpse into Sankyo Kohki’s portfolio comes from the following Komura dealer catalog published in 1965 by EPOI International, Ltd, a subsidiary of Ehrenreich Photo Optical Industries Inc, of New York. In it, 40 different lenses ranging in focal lengths from 28mm to 800mm were shown, supporting “most rangefinder, SLR, and C-mount cameras”.

Looking through the Komura catalog, some versions of the company’s lenses were made with direct mounts to the most popular SLR systems like Canon, Konica, Minolta, Miranda, Nikon, Pentax, and Petri but nearly all of them came in what the company called the “Unidapter Mount”. These lenses were built with a generic screw mount that relied on a series of Komura Unidapters to convert them to other camera mounts. This concept of a “one size fits all” lens mount is essentially the same thing as other universal adapters such as Tamron’s Adaptall system.

The Komura 500mm f/7 was one of these Unidapter lenses that could be fitted with all of the same mounts that the direct fit lenses could, plus a few others such as the Alpa Reflex and Yashica Pentamatic. This would have allowed photographers with more than one system to have a single lens with an upgrade path to other systems if they so chose. Although most of the Komura 500mm f/7 lenses used the Unidapter mount, one additional version of the lens specifically designed for the Bronica medium format SLR was also created. In a dealer catalog from the mid 1960s, the lens had a retail price of $175 with each Unidapter selling for $4.95 each. When adjusted for inflation, these prices compare to about $1650 and $50 today.

The lens was a 4 element in 2 group design in which the entire lens could be broken down into two separate halves with a bayonet mount connecting the two pieces. The front half contained all of the glass elements and the diaphragm, and the rear half contained the focusing helix and the lens mount.

The Unidapter mount is a 39mm screw mount, however it cannot be mounted directly to a 39mm screw mount rangefinder like a Leica or Canon rangefinder without a special Komura reflex housing. It does not appear that Komura’s reflex housing has the same thickness as a Visoflex reflex housing, requiring a separate purchase.

The lens has a 5 degree field of view and supports 77mm screw on filters inside of the front of the lens. Included with the camera was a large metal hood that helps reduce flare, but also adds an extra 3 inches to the camera’s length when mounted.

The entire length of the lens varies depending on the setting of the focus distance and whether you are using the hood. At it’s minimum 26 foot focusing distance with the hood installed, the entire lens is 18 inches long. On a scale, the lens weighs a massive 1653 grams, or just over 3.6 lbs.

To help keep it’s weight in check when mounted to a tripod, the lens has a standard 1/4″ tripod socket right behind the middle bayonet. In the event the screw threads for the lens mount do not allow the lens to mount to your camera with the focus and aperture scales facing up, an adjustment screw near the lens mount allows you to rotate the lens for proper orientation.

The lens normally comes in a zippered case with a purple velvet lining that is molded to hold all of the pieces together. An elastic pouch on the underside of the lid can be used to hold literature or perhaps some accessory filters.

Before using the lens, you must assemble it. The two halves of the lens connect together using a simple bayonet. When it was new, the lens would have had a total of four caps, each covering both ends of both halves of the lens. Amazingly, this example still had all of the caps, not lost to time. After removing the caps covering the middle bayonet, line up a reddish orange dot on the front half with a reddish orange diamond on the back half, and press the two halves together while twisting the front half in the direction of the white arrow. To disassemble, slide the chrome button on the side of the tripod mount in the direction of the white arrow while twisting the lens opposite of how you installed it. The action of the bayonet is very firm, giving reassurance that it is light tight and will support the massive weight of the lens during use.

The build quality of the lens is excellent. Made entirely of aluminum, there is no plastic anywhere that can be seen. Everything on the lens is metal, even the camera’s 4 lens caps that cover both halves of the lens while in storage.

The diaphragm has a total of seven stops from f/7 to f/45, each with firm click stops and is controlled by a thick silver ring on the front half of the lens. The diaphragm itself has a total of 16 blades, giving an almost perfect circle at every f/stop from wide open to fully stopped down. The maximum aperture of f/7 is a curious choice as stopping it down to f/8 offers only a very small decrease in pupil size. In terms of exposure, f/7 is just about a third of a stop faster than f/8, so perhaps the designers of this lens wanted to maximize it’s potential.

Focus is controlled by a very large ring covering about half the total length of the back half of the lens. The entire ring is so big, you can fit almost the entire length of your hand on it while turning. Minimum focus is 26 feet, or 8 meters, which for this focal length is pretty reasonable and extends to infinity. A full twist from minimum to infinity focus requires almost a completely 360 degree twist of the ring. While this amount of movement can be inconvenient on shorter focal length lenses, it is an asset with the Komura as it allows for the greatest amount of precision while focusing.

Unlike other long catadioptric “mirror” lenses like the Soviet MTO 500mm lens in which the lens focuses beyond infinity, the Komura has a firm stop exactly at infinity. Engraved in white and bright orange paint on the outside of the focus helix is an almost useless depth of field scale, with both the focus indicator and a separate IR focus indicator in bright orange. Depth of field scales on long lenses like this are difficult to use as the depth of field is incredibly narrow. Each of the white painted lenses indicating f/45, f/22, and f/11 are just a series of white stripes squished together. They’re so close, there isn’t enough room to print the numbers 32, 16, and 8.

When focused to 200 feet, even at f/22, you still cannot reach infinity within the depth of the lens. When the focus ring is set halfway between 40 and 50 feet, the depth of field at f/45 still fits between both marks. This is most certainly a lens where TTL focusing is a requirement as using this without being able to see through the lens would produce impossibly hard to focus images.

The Sankyo Kohki Komura 500mm f/7 is a wonderfully exotic lens that is built really well, has all the features you’d expect from a premium lens maker who has an excellent reputation behind it, but what it is like to shoot?

The example that I have here already had a Canon FD/FL Unidapter installed on it. I’ve had this lens since 2018 and only realized as I was writing this review that it screwed off. While the lens came to me in it’s original case, there was no original paperwork or a manual included, and none can be found online.

The first time I used this lens, it was while working on the review for the Canon AL-1, an uncommon late entry in Canon’s excellent A-series which was a manual focus body with focus confirmation through an early electronic focus sensor. When mounted to any camera, the camera body hangs off the back, similar to how you would expect to see a camera grafted onto the back of a telescope.

In the previous image showing the Komura mounted to the Canon AL-1, you can see I am using the tripod socket on the lens, rather than the one on the camera. Although the Canon AL-1 does have a metal lens mount, the Komura would absolutely destroy it if I tried to support the camera with the lens hanging off it. Instead, using the tripod socket on the lens allows for pretty good balance.

In that image, I am photographing a clock tower on top of the old courthouse in Crown Point, Indiana. After making an exposure, I removed the Komura and mounted a standard 50mm f/1.8 lens and took a second shot while standing in the exact same spot as the tripod. The two images are below.

In a previous lens review of the Soviet KMZ MTO 500mm mirror lens, I pitted that lens against two other 500mm lenses, this Komura, and a Spiratone Minitel 500mm mirror lens I also own. I shot all three lenses mounted to a crop sensor Fujifilm X-T20 digital mirrorless and compared the results showing a few different scenes.

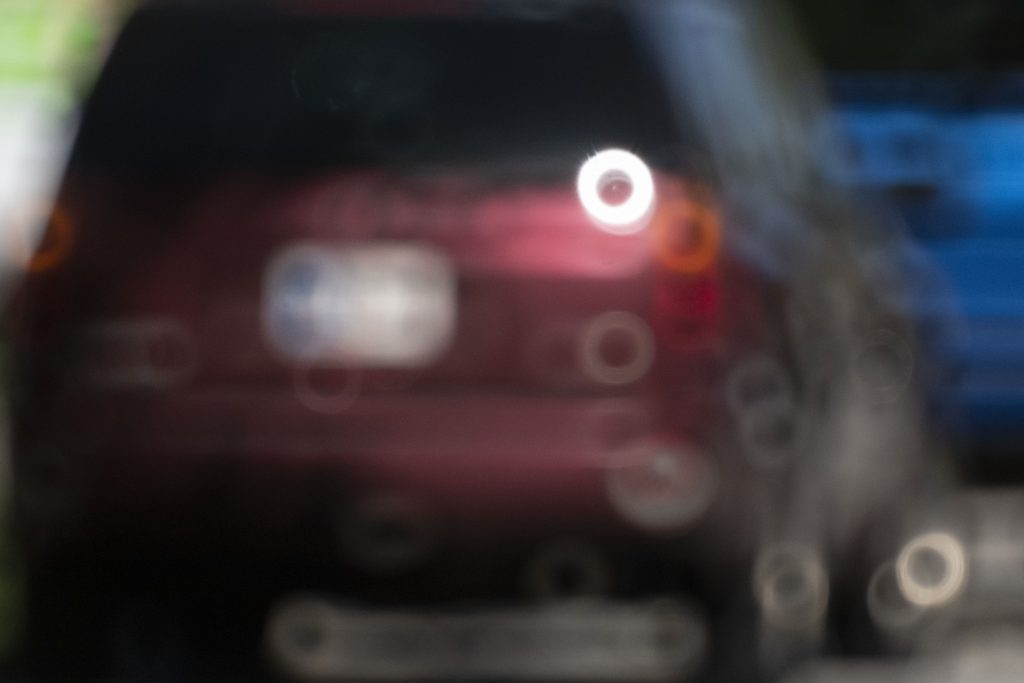

I won’t repeat too much of what I wrote there, as I encourage you to check out that article too, but one area in which the Komura is different from catadioptric “mirror” lenses is in the out of focus details. Mirror lenses use a mirror (as the name implies) to bounce light around two different sets of mirrors. This gives them the advantage of being much shorter in length and lighter in weight than standard telephoto lenses like the Komura. Shooting an 18″ long lens that’s nearly 4 pounds without stabilization is incredibly hard to do, but having a more compact and lighter weight mirror lens allows for greater portability. Of course, the downside to that is the camera can’t have an adjustable diaphragm, but also that the lens design introduces what many people called “donut bokeh” in which out of focus details have a hollow, donut shape to them. In the two images below, I show the MTO mirror lens and Komura intentionally out of focus on a vehicle half a block down the street from my house.

What you get in portability is traded off in distracting orbs throughout your images using a mirror lens. Now, there are some photographers who like “donut bokeh” and in rare examples, can actually use them to enhance the composition of their image, but for general purposes, is usually pretty distracting. If you’re looking for extremely round and smooth out of focus details, the Komura is the clear winner here.

The Komura is definitely a well built lens from a respectable lens maker. It’s fully metal construction and thoughtful design make for a very capable lens, but the time has come to see what the lens could really do.

I’ll start by saying that taking out a 500mm telephoto lens to shoot sample pics for a lens review is a lot easier said than done. The first reason is that this lens is the exact opposite of discreet. Walk anywhere other people go and you’ll stick out like a sore thumb lugging this thing around. You can’t bring it to sporting events or concerts where it might actually be useful, as most places have strict rules about what they call “professional” lenses, and taking it anywhere people are, will generally cause some uneasiness when they see someone they don’t know carrying around what looks like a rocket launcher mounted to a camera. Sure, I could go to a nature preserve and try to get some images of birds, but there’s a reason that nature photographers dedicate their lives to capturing good images of birds…because it’s not easy!

So, what follows is a rather mundane gallery of stuff that may or may not take full advantage of what a long 500mm focal length would offer. I shot the first three film images using a Canon AL-1 SLR, and the digital images using a full-frame Sony a7 II (I upgraded from the crop sensor Fuji). You’ll also notice the last image was my poorly planned attempt at a mirror selfie using a mirror placed on the opposite end of my living room, approximately 18 feet away (when shooting a selfie through a mirror you need to double the camera to mirror distance to get the focus distance so focus was about 36 feet in that image).

Before getting into any critical analysis of the images, shooting a long lens like the Komura requires extra effort not needed with an ordinary 50mm or even a short telephoto like a 105mm or 135mm lens. Stabilization is critical, and shooting a 500mm lens hand held is almost impossible. There is a rule that says that in order to hand hold a lens and still get shake free images, your shutter speed must not be any slower than the reciprocal of the focal length, so a 50mm lens should not be hand held any slower than 1/50, a 135mm no slower than 1/125 and so on.

While this generally works out OK with smaller lenses, things start to break down with long and heavy lenses like the Komura. Simply setting your shutter speed to 1/500 with a nearly 4 pound and 18 inch lens is not going to cut it. Even then, stabilization is necessary as the lens is so massive, it is very difficult to keep it steady. This is where the convenience of modern digital cameras comes to the rescue. Back when this lens was first made, top speeds of 1/1000 were the norm. With today’s electronic shutter cameras, speeds of up to 1/32,000 are possible, and compounded with the fact we can set ISO settings into the hundreds of thousands and still get usable images allows us to get shake free images even with behemoths like the Komura.

Assuming you’ve sorted out getting steady images from the Komura, the next thing that you’ll notice is that compared to a 50mm or short telephoto lens, the images from the Komura aren’t perfect. Contrast is a little on the low side and there is some softness near the corners. In color photos, there are some chromatic aberrations and purple fringing, especially near the edges. Interestingly, the images shot on film actually look better than the digital images as I believe the grain and lower resolution than digital actually helps mask the lower contrast, fringing and other aberrations.

This is where it is important to remember, this is a nearly 60 year old lens. Sharpness is good across the frame, making reading text from hundreds of feet away pretty easy. In a previous comparison I did with this lens, I noted that unlike some lenses where stopping it down improves sharpness, I didn’t notice much of a difference between f/7 and f/45. That the images look as good as they do, is impressive. When the Komura first came out, the image quality was likely championed as an outstanding achievement. Remember, film less cameras with sensors that capture millions of pixels which allow you to crop images like we can today was a futuristic dream back then. Within the confines of a 24mm x 36mm film exposure, the Komura was great.

Even today, using my Sony A7 II, the images are quite good, certainly better than any sub $1000 zoom lens that covers 500mm. Compared to some kind of 20x superzoom point and shoot digital camera, the results from the Komura easily hold their own, and that’s pretty cool to me.

Take away color and shoot this lens on a black and white film that has a bit of extra contrast, and the images you’ll get are going to be really good. You simply can’t get this quality from consumer zoom lenses. Sure, Nikon, Canon, and Sony make lenses that cover 500mm today, but be prepared to save up at least a couple month’s worth of mortgage payments to afford it. That you can achieve pretty good results at 500mm using a 60 year old lens that can be had on the used market for under $200 is a steal and where this lens really shines.

Almost nobody is going to use a 500mm f/7 manual focus lens as their every day lens. This is a special purpose lens that you take out for specific reasons, like to shoot an eclipse, or try to capture a nesting bird from across a field, or maybe to shoot little league baseball from the outfield bleachers. For those purposes, this is a heck of a lens, it’s not perfect, but it doesn’t have to be.

Thanks for the history of Sankyo Kohki – you found some truly obscure info, especially that full range catalog. I had this same lens, plus the 400mm one-piece model, both in LTM39. I shot them with the necessary adapters on a fullframe Pentax K-1 DSLR, and was not impressed with the sharpness of either. True, the 500’s design is unique – and makes good sense to the travelling photographer – but IMO it lacks the most important aspects of a long lens: Good sharpness and high resolution.

The Komura 500mm f/7 lens takes me back to the 1980’s, when Shutterbug Ads was the national photographic equipment want ad newspaper. At the time, I had used lenses up to 400mm all glass and a Spiratone 500mm f/8 mirror lenses. The former made me wich for something longer, the latter, something with f/stop control for depth of field.

A 600mm f/5.6 Nikkor came up for sale, so I jumped at this two piece optical wonder. I was using a Welt/Safelock PT3 tripod, which was fine for 400mm lenses, but far too light for the 600mm Nikkor. I was somewhat interested in photographing surfers, but soon discovered that a 1200mm lens might do it from shore, but “in the water with a short lens” was best. (Just like concert photography; the press/backstage pass makes long lenses unnecessary.)

Heat waves/atmospheric disturbances produced long range, fuzzy images. Finding a subject that wasn’t spooked or moved to fast to track was a major problem. I eventually sold it to a motorcycle race photographer and went back to 300mm lenses just as film photography was getting bumped aside by digital photography. I do recall that an “I-Beam”-type brace that used both the camera and lens tripod sockets produced better results, if you could find/build one. Fun times, even with H&W Control Film (ASA 80).;)

Thanks for sharing your story, Patrick. Although I wasn’t active in photography back then, I can imagine seeing these monster lenses in camera store windows and in printed catalogs must’ve evoked quite a bit of GAS back then, even if that’s not what people called it. The practicality of these lenses however mean that many can still be found in excellent condition today as they likely were not used very often.