Nikon is not only one of the most successful camera companies of all time, but they also have one of the most fascinating histories of any modern company, in any industry today.

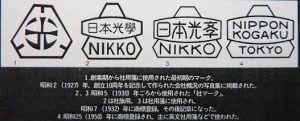

In 2017, Nikon celebrated it’s 100th anniversary with a pretty cool anniversary website (which has since closed) and a series of “anniversary” products that collectors could buy adorning specific logos and insignias commemorating the occasion.

In 2017, Nikon celebrated it’s 100th anniversary with a pretty cool anniversary website (which has since closed) and a series of “anniversary” products that collectors could buy adorning specific logos and insignias commemorating the occasion.

For any company to exist for 100 years is a great occasion and not something that happens often, and if you’re someone like me who loves history, you might wonder what kind of stories there are to tell over the past century. What was the company up to in 1917 when they were first formed, and what kinds of cameras did they make? You might guess that Nikon had some really interesting folding cameras or large format plate cameras to compete with the German models of the time.

Early History

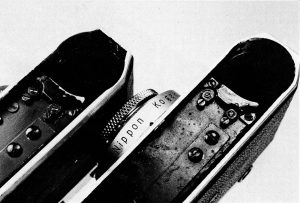

The reality is, Nikon’s early history is quite different than you might expect. For one, the company wasn’t always called Nikon, it’s original name was Nippon Kōgaku Kōgyō Kabushiki Kaisha, or Japan Optical Industries Co., Ltd. It didn’t even officially become Nikon until 1988. The name “Nikon” didn’t appear on a consumer facing product until 1948 with the release of the original Nikon 35mm rangefinder camera. Prior to 1948, Nippon Kogaku was almost entirely a supplier for the Japanese military, most specifically it’s navy.

Nippon Kogaku was officially formed as Japan’s primary optical company on July 25, 1917 after the dissolution of at least 3 prior companies, Iwaki Glass Seizo-sho, Tokyo Keiki Seisaku-sho, and Fujii Lens Seizo-sho. Prior to 1917, Japan was in a state of rapid industrialization and a great priority was placed on developing a military presence in the Pacific region.

Japan, being largely an island nation, invested heavily in it’s navy, referred to as the Imperial Japanese Navy. The ability for Japan to exert control over the Pacific region heavily relied on the performance of it’s Navy which gave them a lot of influence over Japanese industry. Between 1894 and 1945, Japan would participate in 3 significant wars with neighboring China and Russia, relying heavily on imported submarines, military ammunition, and optics from various Western countries. At this time, Germany was considered the leader in the optics industry with quality cameras and lenses developed by companies like Zeiss, Voigtländer, AGFA, and others. The Emperor of Japan decreed that Japan should reduce it’s reliance on imported goods and become more self-reliant. For optical products such as submarine periscopes, rifle scopes, and other lenses, Japan struggled to match the quality of the products being produced in other countries. Early Japanese optics companies were unable to duplicate the precision parts and lenses that the Germans were already producing.

By 1917, World War I was well under way causing Japan to lose it’s link to Europe and it’s supply of optical goods. The Imperial Japanese Navy needed to find a way for Japan to develop a self-reliant optics industry. As a result, each of the three biggest Japanese optics companies combined forces to make one single Japanese optics company which became Nippon Kogaku. The plan worked, and by coordinating all of the country’s top minds together, working for a common goal, Nippon Kogaku was able to bridge the gap in quality between Japanese and German products.

After the conclusion of the first world war, Germany’s economy was in shambles, and many of the technicians and engineers that once had jobs in German optics companies became unemployed and were desperate for work. In 1921, eight German engineers were hired by Nippon Kogaku with a contract to last no less than 5 years. Of the eight Germans, the two most significant were Heinrich Acht who was principal engineer of product design, and Professor Max Lange, who was in charge of optical lens design. Not much is known about where each of these eight German engineers might have been employed prior to coming to Japan, but it was likely not difficult to convince them to relocate to Japan and work for an otherwise unproven optics company. After the expiration of the original 5 year contract, Heinrich Acht would remain employed by Nippon Kogaku for another 3 years.

During their stay in Japan, the eight German engineers helped expand Nippon Kogaku’s product portfolio to include telescopes, binoculars, and aerial photographic lenses. Their first photographic lens was a direct copy of the 4-element Zeiss Tessar lens called the Anytar. The Anytar’s design was overseen almost exclusively by Heinrich Acht during his stay in Japan. After his departure, the Anytar continued to be refined, until eventually reaching or even exceeding the quality of the original. The Anytar lens was only made in pre-production form and never sold to the public. The only known copies are in the Nikon Museum in Japan.

First Success

Over the course of the next 10-15 years, Nippon Kogaku’s ability to produce lenses, rangefinders, and other equipment grew tremendously, and in some cases exceeded the performance of the German product the Japanese had hoped to copy a few years prior. Yet, despite their rapidly increasing capabilities, hardly anyone outside of the Japanese military knew about it. With only one exception, Nippon Kogaku’s sole customer was the Japanese military, specifically the Imperial Japanese Navy. Nippon Kogaku had no commercial or retail sales, there was no marketing department, they did not have a distribution network, simply, no one knew of their existence, not even the Japanese people.

One of the side effects of primarily making military products, the concept of cost was rarely an issue. Nippon Kogaku had no sales goals or competition to keep up with. When they were assigned a goal, they worked hard at it until it was right, no matter the cost. The demand for extremely high quality products for military use, combined with an immense sense of national pride, resulted in extremely well made products.

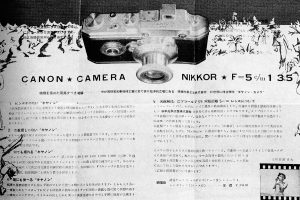

Perhaps foreshadowing a future in consumer products, the one exception where Nippon Kogaku ventured into the consumer realm was an agreement in the mid 1930s with another Japanese company called Seiki Kōgaku Kenkyūjo, or Precision Optical Instruments Laboratory who was working on what would become Japan’s first 35mm interchangeable lens rangefinder camera. The camera, eventually named the Hansa Canon was Seiki Kogaku’s first commercial product and bore the name “Canon” for the first time, a name which in 1947 the company would adopt.

Unlike Nippon Kogaku, Seiki Kogaku was a very small shop, started by a modest repair technician named Goro Yoshida, Yoshida’s brother-in-law Saburo Uchida, and a third man named Takeo Maeda. Together, the three men worked on the mechanical design of the camera, but lacked experience with lens and rangefinder design. Realizing that consumer cameras could benefit both civilian photographers and the military, the Imperial Japanese Navy tasked Nippon Kogaku to help companies like Seiki Kogaku design the optical rangefinder, lens mount, and lenses for the new camera.

It might seem strange today to think that two primary competitors like Nikon and Canon would collaborate together on a project, but back then the Japanese had a more unified approach in which companies would work together for the betterment of the Japanese people. Even without that philosophy, keep in mind that Nippon Kogaku would not have seen Seiki Kogaku as a competitor. Nippon Kogaku exclusively made products for the Japanese military, not for consumer consumption. It’s partnership with Seiki Kogaku allowed the Japanese military access to future products for military use.

Shortly after the Hansa Canon’s release in 1936, Nippon Kogaku, along with the rest of Japan became increasingly focused on the Second Sino-Japanese War. On, July 7, 1937, Japan would declare war on the Republic of China over it’s interests in the Pacific Region. This was the second time Japan aggressively battled it’s neighbor, claiming control over land in Manchuria and coastal China. Aided with support from the Soviet Union and the United States, this war would eventually merge in with the rest of World War II when Japan famously attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.

War

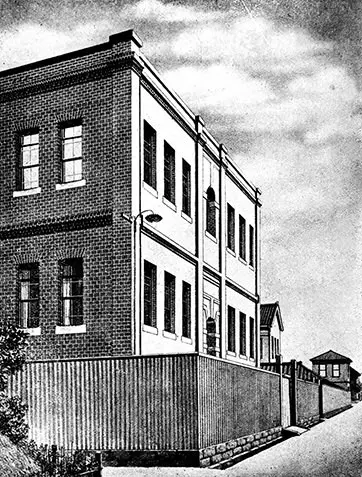

Although a terrible act, Japan’s involvement in these various conflicts meant that companies like Nippon Kogaku who supplied the military, were given near unlimited resources and funding to develop and refine new and existing products. Prior to the war, Nippon Kogaku already had an excellent understanding of optics design and quality control, but the demands of war pushed them to even higher standards. Nippon Kogaku was put under enormous pressure by the Imperial Japanese Navy to refine and improve nearly every optical product. At the time of it’s inception in 1917, Nippon Kogaku employed approximately 200 workers at a single manufacturing plant, but by 1945 had expanded to over 25,000 workers at 24 different facilities.

There were other Japanese optics companies at the time such as Tokyo Kōgaku K.K. (later Topcon), Chiyoda Kōgaku Seikō K.K. (later Minolta), Asahi Kōgaku Kōgyō K.K. (later Pentax), Riken (Ricoh), Konishiroku (Konica), Fuji, and a few others, but Nippon Kogaku was by far the largest and most sophisticated of them all. Making nearly every type of optical instrument used by the Japanese military, they made periscopes for submarines, aerial cameras, rifle scopes, binoculars, bomb sights, optical rangefinders, loupes, surveying equipment, and other products.

What would end up being two of Nippon Kogaku’s biggest achievements were significant advancements in refining the raw materials needed to make glass for their lenses and lens coatings that would improve clarity and contrast. The processes for cultivating, refining, grinding, polishing, and annealing (cooling) the glass used in it’s lenses gave them a level of clarity and sharpness as of yet not achieved by the Germans. The other was new advancements in lens coatings that would reduce flare and improve clarity.

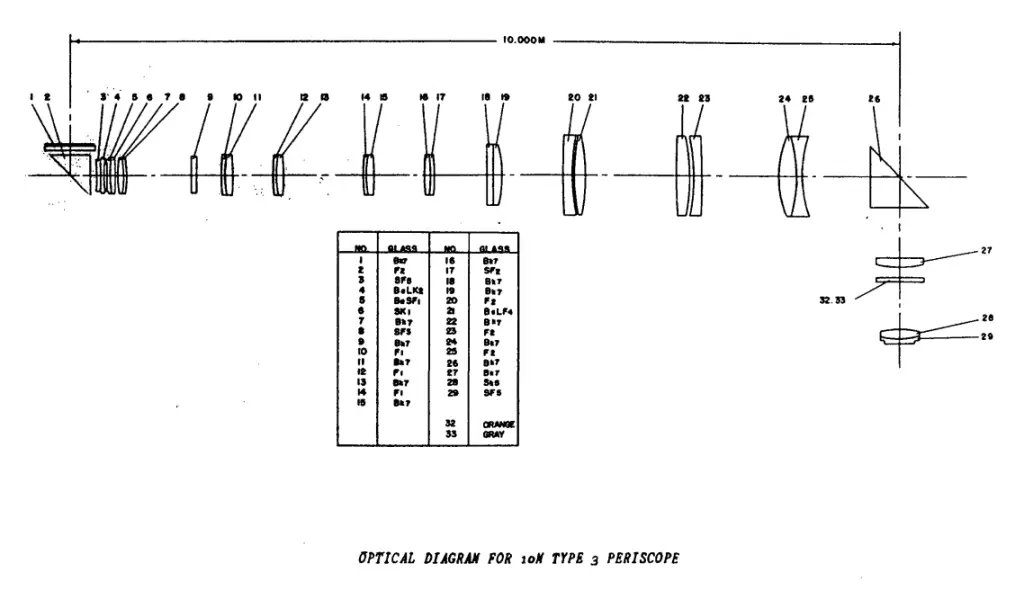

Both advancements in glass production and lens coatings had tremendous benefits in both optical rangefinders and periscopes mounted to Japanese submarines. Nippon Kogaku made it’s first periscope in 1918 and these early designs were simple copies of existing German designs, but like everything else the company made, they continued to improve the designs, far exceeding the originals which they were based off. The most common style of periscope built by Nippon Kogaku during this time was a 10 meter long periscope that used 33 individual glass elements. Each time light passes through a piece of glass, no matter how well refined it is, some light loss will occur. But when you pass light through 33 different pieces of glass, the amount of lost light is dramatic. This limited their usability to daylight hours when there was enough sunlight to overcome the light loss.

To reduce light loss, Nippon Kogaku developed two different methods for lens coatings, the first was a chemical method in which glass was treated with nitric acid, but the second was called an ‘evaporation method’ in which a mineral called cryolite is evaporated and deposited onto glass surfaces in a vacuum. When performed to the internal elements within the periscopes, light loss was reduced, improving usability to lower light times such as dawn and dusk.

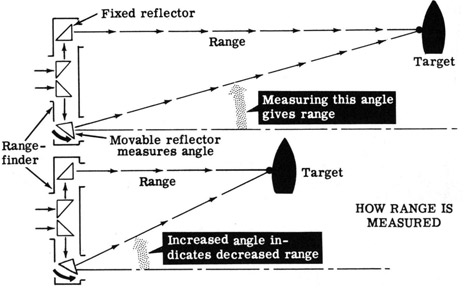

Lens coatings improved optical rangefinder design too. An optical rangefinder is a device in which light travels through two different windows separated by a known distance and through a combination of mirrors or prisms, is converged into a single image. The variation in the two images entering each of the two windows can be used to calculate the distance of the viewed image. The accuracy of an optical rangefinder is heavily dependent on the quality of the glass used and the coatings on them to eliminate optical anomalies such as diffraction.

Nippon Kogaku’s standard rangefinders prior to the war came in a variety of sizes, from 1.5 to 15 meters in length. The larger the rangefinder, the more accurate it can be, especially at great distances. All Japanese naval vessels used various types of rangefinders in what was called their fire-control systems to aid in accurate deployment of artillery and other munitions.

In the late 1930s, the Imperial Japanese Navy had begun work on a new generation battleship which would eventually be called the Yamato-class battleship. In total, only two were ever built, the Yamato and Musashi (a third was built but converted to an aircraft carrier). Weighing over 70,000 tons, each Yamato-class battleship had three 18.1 inch turrets that were said to out range the gun systems on battleships made by any other country. In order to accomplish this goal, the artillery systems on these ships required a level of precision and accuracy henceforth not seen before and with the use of Nippon Kogaku’s new capabilities, a new 15 meter rangefinder system was created that allowed them to accurately target enemies up to 35 kilometers away.

Nippon Kogaku’s glass production and lens coatings provided benefits on all types of optical products, not just periscopes and rangefinders. Warship binoculars received upgrades as well, some weighing as much as 70 lbs each, and requiring a tripod or fixed mast to be used. Hand held binoculars were issued to every single officer in every branch of the Japanese military.

Nippon Kogaku’s lens coating technologies were continually improved throughout World War II. They worked on various other types of night-vision technologies that gave them the edge in night time warfare. The United States and other Allied powers developed advanced warning technologies such as RADAR in the early 1940s and rapidly deployed these to the Pacific fleet allowing them to detect incoming aircraft far before they could be seen. The Opana Radar Site on the island of Oahu, famously detected the impending attack on Pearl Harbor before it happened, but the warning went unheeded, but nevertheless, the system did work.

The Japanese hadn’t yet developed their own RADAR technologies, so they were at a disadvantage in this regard, however their superior night vision capabilities allowed them more precision during night time or low light skirmishes. The American fleet would often have no problem detecting that Japanese aircraft were approaching, but they couldn’t actually see them. The Japanese on the other hand were able to hit their targets and get away in the cover of nightfall before the Americans could accurately locate them.

The Japanese military had quite a few advantages in the early part of the war, due in part to the equipment and technologies built by companies like Nippon Kogaku. Things started to change by 1944 when American forces were able to disrupt the supply of raw materials that were needed to resupply the Japanese military. American bombing raids became more successful at damaging and destroying factories that were producing items for the Japanese war effort. Optics factories for Nippon Kogaku, Fuji, and others were relocated into mountainous areas inland, and in some cases inside of caves. During surveys of Japan after the war, American occupation forces discovered many half built caves and other structures with equipment stored and seemingly ready for use.

The Americans were quite aware that the Japanese had an excellent production system for war supplies and optics equipment, they just didn’t know much about who made them. It is said that on occasion when a Japanese war ship was captured, officers would find binoculars and other optical equipment and marvel at how well they were made. Compared to the German made binoculars and lenses that the American officers had, the Japanese models were superior, which turned them into sought after war souvenirs.

Rebirth of Nippon Kogaku

Japan announced it’s surrender on August 14, 1945, halting all Japanese military and manufacturing. Many of Nippon Kogaku’s factories were damaged or destroyed. The remaining workforce became idle, awaiting instruction from the American occupation forces. The first American forces arrived on the island on August 28, 1945, with General Douglas MacArthur following on August 30th.

US President Harry Truman signed an order on September 6th that set two objectives for Japan, the first was to establish a Democratic and pro-United Nations government, and the second was to strip the entire country of all war production and capabilities. The Imperial Japanese Navy and all of it’s resources were effectively eliminated and all military capacity was in sole control of the US and British occupation forces.

Prior to the start of World War II, the United States was increasingly aware of instability in the Pacific region, not just with Japan, but also with China, Korea, and the Soviet Union. US presence in territories such as the Philippines, Guam, Midway Island, Australia, and the Hawaiian Islands was done as a direct consequence of wanting to maintain stability in this region. After the war, the Americans quickly realized the benefit of having a controlling interest in Japan who they identified as a very valuable future ally. Unlike the Allied Occupation in Germany, the Soviet Union was left out of the division of power and the Americans felt that without their influence, they could gain a stronghold in the Pacific.

In order for the Americans to leverage Japan’s vast work force and ideal geological location, they quickly put into action ways in which they could restore Japan’s economy, albeit with American influence, and help them get back on their feet. The Japanese people were badly affected by the war. Food and medicine was in short supply. Diseases such as cholera, typhus, and smallpox ran rampant. Sewage systems were heavily damaged causing severe sanitary issues and allowed for other various bacteria and diseases to spread uncontrollably.

In the days following Japan’s surrender, President Truman appointed General Douglas MacArthur as the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, or SCAP for short. His job was to establish an office called the General Headquarters, or GHQ that would establish a new economy, oversee welfare programs for Japanese citizens, rebuild infrastructure, housing, hospitals, cultivate crops and food resources, among other things.

Shortly after Allied occupation of Japan, GHQ surveyed all of Japan’s industrial and manufacturing industries in an effort to see which ones could resume making things that could be sold to help rebuild the Japanese economy. Most factories that built wartime goods were shut down and leveraged in other ways. Nippon Kogaku, with such a large workforce, had impressed upon GHQ that despite their role in aiding the Japanese military during the war, might still be useful in a civilian capacity. The company was ordered to put together a list of potential future products that could be built and sold to provide income. In total 15 working groups were created and by September 1945, a list of 38 potential products including things like telescopes, surveying equipment, projectors, clocks, spindles, lights, calculators, and even surgical equipment was created.

Despite having no experience creating items for the civilian market, the first two products to be approved for production were eyeglasses, and a line of binoculars that Nippon Kogaku had made during the war. The reputation of these binoculars from American personnel who had captured them on Japanese ships during the war had earned them a reputation as world class products, so it made sense to resume production on a commercialized version. Nippon Kogaku’s workforce at this time was a mere 1725 workers, down from over 25,000 shortly before the end of the war, but true to Japanese culture, the company worked hard and did their best to use their previous experience in building their new products.

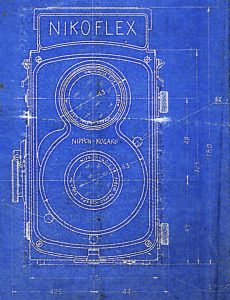

By April 1946, only 8 months after Japanese surrender, Nippon Kogaku’s factories were producing camera lenses, five different types of binoculars, a pocket telescope, a microscope, a water level, land-use and astronomical telescopes, and several types of spectrographs. In September 1946, work began on two new types of cameras, a medium format twin lens reflex style camera, and a small 35mm coupled rangefinder camera with a focal plane shutter.

The smaller rangefinder camera was chosen for production and given the name “Nikorette”. A production run of 20 prototypes were completed in late 1946 and given the name “Nikon”. A combination of supply shortages and Nippon Kogaku’s desire to create an entirely new camera from the ground up caused delays in bringing the camera to market. Nippon Kogaku’s experience during the war meant they had no difficulty creating lenses and the rangefinder system for the camera, but they struggled in several other areas.

It is said that when deciding upon the features of the new camera, Nippon Kogaku looked at both the Leica III, and the Zeiss-Ikon Contax and picked the best features from both cameras. The new camera would share a similar body design, including removable camera back, and bayonet lens mount from the Contax, but would have the horizontally traveling shutter and simpler rangefinder system from the Leica.

The Contax mount was a German design that was notoriously complicated and this caused many production problems. Nippon Kogaku had experience with this mount, creating their own version for Seiki Kogaku in the 1930s for the Hansa Canon, but still struggled with the complexity in their new camera.

In addition to the mount, they also had problems with the shutter. For one, the precision required to get the shutter timings right required a very precise amount of tension, which required a quality spring, something the Japanese did not have experience with. After trying various different designs, Nippon Kogaku decided upon a spring made of Swedish steel, as the Swedes had great experience in precision watches and other spring loaded devices. The rubberized coating on the cloth shutter was also a problem too. Nippon Kogaku experimented with coatings made by a huge number of companies, including Kodak, a company that made parachutes, and even a rubber boot manufacturer. This was one thing that changed more than once after sales of the camera had begun, so there can sometimes be a huge variance in the quality of the coating seen today.

Finally, the process for plating the body of the camera was a huge problem as supplies of chromium were extremely limited and required advance approval from GHQ. Early Nikon rangefinders have been seen with at least 4 different chrome finishes. Some are very shiny and smooth, others are coarse and dull. If you had multiple cameras and tried to swap parts from one camera onto another, the finish likely would never match up.

As they had with pretty much everything they had ever done prior, Nippon Kogaku did not give up and in March 1948, the camera was ready for sale. But to whom? In the years since it’s foundation in 1917 through the end of the war, no one knew who Nippon Kogaku was. Nikon was not a household name. The Japanese camera industry was still in it’s infancy, and anyone outside of Japan who wanted a professional level camera would not have taken anything made by an unknown Japanese company seriously.

The Japanese people were still largely suffering from the war, unemployment was high and people didn’t have a lot of money to spend on frivolous expenses like a new camera. Even if they wanted to, the goal of the GHQ was to bring money into Japan, and selling things to it’s own people would not accomplish that. In the first few years the Nikon rangefinder was produced, almost all models were sold for export.

Of course things got better. The experience gained by Nippon Kogaku as a supplier of military goods helped enable them to overcome its initial postwar difficulties and initiate production in a relatively short time frame. Added to its knowledge base in the fields of optical glass and photographic lens production, prior successes in lens coating left Nikon well positioned to enter the U.S. and European camera markets by 1950.

In April 1946, a soft optical coating was applied to the surfaces of the lenses inside the barrels of its Nikkor lenses to improve the transmission of light through the instruments. Cryolite was initially used, as it had been during the war, but by 1948 the primary ingredient was changed to magnesium fluoride, and the anti-reflective coatings were substantially hardened. Together these improvements enabled corrections to the optics through the addition of more optical elements without compromising the transmission of light like in their early periscopes. The coatings also played a role in significantly reducing internal reflections or ‘flares’, which improved the performance of the company’s large aperture and wide-angle lenses.

All told, these chemical coatings of the internal surfaces of Nippon Kogaku lenses were the key feature that enabled them to quickly surpass German lenses in their optical performance after the war. The continuum of their technological research had clearly not been broken by the company’s abrupt transition to consumer production. Nippon Kogaku was able to capitalize directly upon its successes in the war and modify them to suit the needs of its new markets despite the nearly total evisceration of the company’s manufacturing base. By the mid-1950s, the superior quality of Nikon’s photographic lenses and cameras came to be recognized worldwide.

References

A large part of the information from this article is credited to various discussions I’ve had with Nikon historian and President of the Nikon Historical Society, Robert Rotoloni, but I also must credit the excellent work by Michael Wescott (Wes) Loder and his book “The Nikon Camera in America, 1946-1953”, an online article by Hans Braakhuis called “The History of Nippon Kogaku 1600 – 1949”, and finally one more by University of British Columbia student Jeff Alexander PhD called “Nikon and the Sponsorship of Japan’s Optical Industry by the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1917 – 1945”.

Each of these four sources did far more work digging into the history of Nippon Kogaku than I ever could do on my own. In fact this entire article is merely an amalgam of all that information dissected and pieced back together for you to read.

If you find the history of Nippon Kogaku interesting, I strongly recommend checking out either of Robert or Wes Loder’s books. Robert has autographed copies of his book available if you are interested. You can contact him directly by sending an email to rotoloni at msn dot com.

Finally, while I was in the midst of writing this article, I participated in Episode #51 of the Classic Lens Podcast with Robert Rotoloni where we discussed many of the same topics presented in this article. If you would rather hear this information straight from the source, I highly recommend checking that out as well.

Somewhere I have a Nippon Kogaku trench periscope- a WW2 era copy of a British WW1 design.

Fantastic addition to the Rotoloni Report series, Mike! It was great having you and Bob on the Classic Lenses Podcast to hear his stories about Nikon’s history. This deeper-dive is a fantastic read!

Fascinating historical insight — thanks! One suggestion: the article’s credibility suffers from basic grammar issues that a spell checker could have prevented. For example, the use of “it’s” instead of the correct “its” occurs 19 times (no, I didn’t count them, but a run through spellcheck highlighted every one). Just to be clear, “it’s” is short for “it is”. “Its” is the possessive pronoun needed in these 19 instances. Does this matter? Whether producing precision machinery or crafting a well-written article, correct use of the right tools (like spellcheck) counts. Great historical information — thanks again!

Thanks for the feedback Frank. I like to think of myself as an amateur at this. I do the best I can, but I dont want to be too perfect, otherwise people would expect perfection every time! For what its worth, WordPress does not auto detect its as being incorrect. Im not saying it isnt, it just doesnt catch it like you suggest! 🙂

Invaluable information compiled in this article for us. Thanks a lot !!!.I wait for your next !!!.