This is a Voigtländer Vito II 35mm folding camera which was in production from 1949 – 1954. The Vito II was the successor to the earlier Vito model which was introduced in the late 30s as Voigtländer’s first 35mm camera. The first Vito did not use standard 135 format 35mm film, but instead was designed for unperforated paper backed 35mm film similar to Kodak’s 828 format. Later models were updated to accept perforated film via a feeler shaft for film transport. When the Vito II was released, it could only accept standard 135 format cassettes. It was a well built and popular camera that competed directly with the Kodak Retina and AGFA Karat which were both German designed folding 35mm cameras. After this model was discontinued in 1954, the “Vito” name continued to be used by Voigtländer in a variety of compact 35mm cameras through 1971.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: Color-Skopar 50mm f/3.5 coated 4-elements

Focus: Scale Focus Viewfinder

Shutter: Prontor-S Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/300 seconds

Exposure Meter: none

Battery: none

Flash Mount: PC port X-sync

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/voigtlander_pdf/voigtlander_vito_ii.pdf

History

Voigtländer was founded by Johann Christoph Voigtländer in Vienna, Austria in 1756. While ownership of the company has shuffled and been reorganized a couple of different times over the years, the Voigtländer brand is not only the world’s oldest optics brand, it is one of the oldest brands in any industry in the whole world.

In the 18th century, Voigtländer was a maker of scientific instruments such as navigational tools like compasses and astrolabes. Voigtländer held state-owned patents from the Austrian government which granted them exclusive rights to produce these instruments, so its likely they were the only company making them.

Johann Christoph Voigtländer would die in 1797 and the company would pass onto his widow and three sons. In the early 19th century, the company would expand its product portfolio to include early optical instruments. In my research for this article, I could not find many specific references to what Voigtländer made in the early 1800s, but my guess would be military or naval type products like scopes or binoculars, or perhaps even eye glasses. I found some information saying that in 1823, they made opera binoculars.

Voigtländer’s earliest photographic products seemed to start around the year 1840 when they introduced the first optical lens designed using a modern understanding of mathematics and the physics of light. This first lens was called the Petzval lens and was designed by Hungarian Professor Jozef Maximilián Petzval. Prior lenses to the Petzval were just curved pieces of glass with little to no thought put into the physics of how light would pass through them.

Disclaimer: In an effort to not get too far off topic for this review, I will do my best to type a very short summary of the earliest days of photography. This is a topic that spans nearly a century and could fill many chapters of a book. I will gloss over many aspects of these earliest days, so please excuse me if I leave a lot out! 🙂

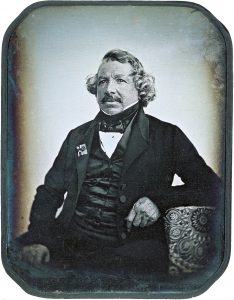

One of the first types of photography was called the ‘daguerreotype‘ which was invented in the 1830s by French inventor, Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre. The process of making a daguerreotype starts with a silver-plated copper plate. That plate is first buffed and polished until it looks like a mirror. Then the plate is sensitized to light over iodine and bromine in specialized, light-proof boxes. These early boxes didn’t have lenses in the traditional sense. Many used pinholes where a very small hole was drilled into a piece of metal or wood that would use refractive properties of light to make an image on the light sensitive plate. The earliest glass lenses were still very small with very small apertures that would let very little light in.

A typical daguerreotype image would take many minutes to capture as it took a great deal of time for the image to be exposed by the reflective surface of the plate. As a result, the earliest photographic images were typically still lifes or landscapes. For a person’s portrait to be captured, they would need to sit still for a very long time, sometimes as long as 10 minutes without moving. Early daguerreotype portraits were taken with people sitting in specialized chairs with braces that would hold their head, neck, and arms in a fixed position for the necessary amount of time.

The Petzval lens was significant because its aperture was around the modern equivalent of f/3.7 which meant that it could let in a great deal more light than the pinhole lenses previously used. This meant that an image could be captured in as little as 30 seconds instead of 10 minutes, making it much easier to capture someone’s portrait.

Voigtländer’s first camera was an all-metal daguerreotype released in 1841 called the Daguerreotyp-Apparat zum Portraitiren. This camera was made of brass and was shaped somewhat like a bowling pin. There was a fat end where the lens resided, and a thinner end with a ground glass focusing screen and a magnifying eye piece that the photographer would use to get the image in focus. These early cameras did not have any type of shutter. A lens cap was manually placed over the end of the tube to prevent light from entering the camera. Once the photographer had his image composed and in focus, he would put the lens cap back on, cover the camera using a box or a dark cloth, and remove the back section that contained the ground glass and eyepiece. He or she would replace this part with a traditional daguerreotype plate and then would remove the lens cap for whatever length of time was needed to expose the image. Upon completion of the exposure, the lens cap would be placed back on the front of the camera, and the entire apparatus would be moved into a dark room, where the plate would be removed and developed. As primitive and complicated as this sounds today, this was groundbreaking stuff back then. Prior to these early daguerreotypes, the only way we could capture an image was by paint.

Over the course of the next 2 decades, Voigtländer would continue to be the world leader in photographic lens manufacturing. In 1862, the company would produce its 10,000th Petzval lens. I could not find any indication of how much competition they had around the world at this time, but my guess is, there wasn’t much. The daguerreotype would remain the dominant form of photography during this time, but would eventually fall out of favor to two other methods, known as ambrotypes, and tintypes. Each of these methods used glass and tin respectively and were developed using different chemicals. While the concept of an ambrotype and tintype was similar to that of a daguerreotype, they weren’t the same thing. Glass and tin plate cameras would remain popular until the 1880s when the Eastman-Kodak company would invent the concept of photographic film.

In 1868, Voigtländer’s company headquarters would relocate from its original location in Vienna, Austria to Braunschweig, Germany where the company would remain until at least the end of World War II.

Although Voigtländer had success with their early metal daguerreotypes, their primary success came from continued production of their Petzval lenses which were used by a variety of camera makers. Even after the daguerreotype was superceded by newer technologies, the Petzval remained a popular choice for portraiture photography.

Voigtländer wouldn’t release another camera until around 1890 (some sources state it was after 1900), when they would release a Reisekamera which is a generic name meaning “travel camera” in German. Many manufacturers made similar style cameras and it can be extremely difficult to identify who made a particular Reisekamera because the parts were wooden, modular, and lacked any unique differences between all the companies making them at the time. So while it is possible Voigtländer had a variety of these style of cameras, it is almost impossible now to identify them as an actual Voigtländer model.

As film photography would gain momentum in the 1900s with models from The Eastman Kodak company and other German makers, Voigtländer would eventually make a more serious effort into designing their own cameras. In the first two decades of the 20th century, the company would release a wide range of folding plate cameras with names such as Scheren-Camera, Alpin, Stereophotoskop, and Avus. Also around this time, Voigtländer would begin to experiment with new, more advanced lens designs which would be called the Heliar, Dynar, and Kollinear lenses. Each of these lenses would be predecessors to the Skopar and Color-Spokar lenses which would be extremely successful later in the 20th century.

Voigtländer had great success around this time as both a maker of fine plate cameras and lenses. In 1915, the company would outgrow its original factory in Braunschweig and would move to a larger facility on the other side of the town. When the first World War broke out, Voigtländer would make military products for the German war effort.

After the war however, the company struggled due to the collapse of the German economy. Several key employees would leave the company such as Rudolf Heidecke and Paul Franke who would form their own company Franke & Heidecke, who would later be known as Rollei and would become one of the premiere German camera makers of the 20th century.

Things would stabilize around 1925 when Voigtländer would be acquired by German chemicals company, Schering AG. By 1929, the company would see great success making more consumer oriented roll film models such as the original Bessa. The Bessa name would be the company’s most successful line of cameras starting as 6×9 folding roll film cameras, and evolving over the next 80 plus years into a digital camera which is still sold today.

Throughout most of the 1930s, Voigtländer would mainly stick to medium format roll film cameras like the Bessa, the Perkeo, and the Inos. The company would be one of the last German companies to release a ‘miniature’ camera using the new 35mm format which was popularized by Leitz, Zeiss-Ikon, and Kodak. Many other German camera makers such as Balda, Welta, and Ciro would all have competing 35mm models before Voigtländer’s first 35mm model, the Vito which was released in 1939. The first Vito was designed for unperforated 35mm cinema film and made 30mm x 40mm exposures. This original Vito was made only for a short while in 1939 and early 1940 until production was halted due to the start of World War II.

It wouldn’t be until 1947 when Voigtländer would resume production of the Vito. By this time, the source for the original model’s unperforated film was no longer in business, so the camera had to be redesigned with a feeler shaft to accept perforated 35mm cinema film loaded in special canisters. While not specifically designed for Kodak’s 135 format 35mm film, this article by John Margetts suggests that a regular Kodak 135 cassette fits fine on both the takeup and supply sides of the camera. While researching this article, I found conflicting info that says the original Vito was designed for 828 film which was also an unperforated roll film capable of 30mm x 40mm exposures, however I have my doubts that this is true since 828 film was alive and well long after World War II. It would remain in production until the 1980s, so Voigtländer would have had no reason to abandon it. Whether the original format was 828 or some other proprietary format, the new model would make standard 24mm x 36mm exposures like its primary competitor, the Nagel designed, Kodak Retina.

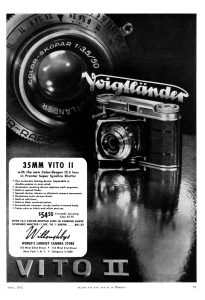

The original Vito I would remain in production until 1950, but a year before its discontinuation, a new model called the Vito II would be released which improved upon the original model by adding full support for Kodak’s 135 format 35mm film. This meant that a photographer no longer needed to use special canisters or bulk roll his or her own film to use the camera. By this time, 135 format 35mm film had become one of the most popular film formats in the world, and Voigtländer basically had no other choice but to support it. The ad to the left from the April 1952 issue of Modern Photography shows the list price of the Vito II was $54.50 with the Prontor shutter, and $61.25 with the Compur shutter, which is comparable to $501 and $563 today.

In addition to support for 135 format film, and an all new film transport system, the other major change with the Vito II was that the lens was now the Color-Spokar coated lens, which was optimized for color photography. The Vito II would remain in production until 1957 but would receive several minor changes along the way. Later Vito IIs could be had with a variety of shutters, some with flash synchronization, the shutter release bar would become a button, and eventually an accessory shoe would be mounted to the top of the camera. The model being reviewed here has flash synchronization and the later shutter release button, but lacks an accessory shoe.

The Vito line was very successful for Voigtländer and had many different variants. Some of the more notable variants were:

- The Vito III was a folding camera with rangefinder attached

- The Vito B was a non folding solid bodied version of the Vito II

- The Vito IIa would be a folding camera like the Vito II, but with a flat, more streamlined top plate.

By the 1960s, the Vito name would represent the company’s entry level line of compact 35mm cameras. The last models to bear the Vito name would be released as recently as 1971.

In the following decades, Voigtländer would be sold and acquired a number of times. In 1956, it would be acquired by the Carl Zeiss Foundation. In 1973, Zeiss would sell the company to Rollei until Rollei’s collapse in 1982 at which time a company called Plusfoto owned the brand. Voigtländer would be sold once again in 1997 to a company called Ringfoto who still owns them to this very day. In 1999 Ringfoto would lease the Voigtländer brand to Japanese company, Cosina who produced a line of Voigtländer branded film and digital cameras and lenses. In October 2015, Cosina would discontinue the last of the Voigtländer digital cameras, but would continue to sell Voigtländer branded lenses with a variety of popular digital camera mounts.

Today, many Voigtländer models are highly sought after. The later Bessa models and the Vitessa models with Color-Skopar lenses can still go for several hundred dollars. The Vitos are slightly less desirable, but examples in good working condition can sometimes approach $100. The Vito II’s primary competitors were the type 013 and 015 Kodak Retinas and AGFA Karat/Karomats. All of these cameras were nearly the same size folding cameras, with excellent optics, and a scale focus viewfinder. The used market for Retinas are generally higher than that for the Vito, but it is certainly not because of the quality of the camera.

My Thoughts

Voigtländer is a marque that I became aware of in the early days of collecting cameras. I lusted after their Bessa line of cameras, the Prominents, and the various other high end models. Most of the time, I considered their products to be out of my price range and I stopped looking for them.

Sometime last year, I saw my first Voigtländer Vito and thought it was a really handsome looking camera and after seeing a few selling on eBay for close to my price range, I added them to my radar. I found this particular example with a $40 Buy it Now price, but the seller had the Make an Offer option available so I offered $25 and they accepted. Score!

When the camera arrived, I was pleased that it was in good working order. Everything seemed to be in excellent condition. The shutter worked at all speeds, the bellows showed no signs of decay, and the lens was mostly clear. I did a quick wipe down with some high content Isopropyl Alcohol and loaded in some film.

The first reaction I had when I held this camera was how compact and solid it felt. This camera is very comparable to the Retina I from the same era. I would suspect that the Retina was the Vito II’s primary competitor in the market when it was being sold. The overall size between the two cameras is very similar and although I do not have a scale handy, I suspect that the weight of the two is very similar as well.

The Vito II fits very easily into most pockets. You can slip it into the front pockets of jeans, or even the pocket of a dress shirt. This makes the camera great for spontaneous shots since it is so easy to store in a handbag, coat pocket, or even the glove box of your car. It is not difficult to bring with you and have ready if you need to take a quick shot.

To open the camera, you press a small button on the bottom plate of the camera and the front door springs open. It might at first look like this button is a rewind button like on many rangefinder and SLR cameras, but its not. The lens is self erecting just like on the Retina, so upon opening the door all the way, the lens will draw out to its fully extended position and the camera is ready to shoot.

The Vito II has double exposure prevention which prevents you from firing the shutter until after you advance the film. Due to how this mechanism works, you need to have film loaded in the camera in order to disable this double prevention system. You will not be able to press the shutter release unless the internal film sprockets are rotated. If you do not have film in the camera and would like to test for proper operation, you can open the film door and spin the sprockets by hand until they stop.

Opening the camera is a little different from any other camera I’ve used. Unlike most cameras with a sliding latch, there is just a “locking ridge” on the side of the camera. To open the camera, hold it with your left hand with the left side of the camera facing up. Then with your right hand, use your right thumb to pry up on this locking ridge and the door will open. It almost seems too simple. I am amazed that this works at all to keep light out of the film compartment.

Loading film into the camera is pretty uneventful. It loads in a traditional left to right manner. The take up spool has a single slit and spins counterclockwise. Like the Kodak Retina, the frame counter must be manually reset after loading new film into the camera, but unlike the Retina which counts backwards, the frame counter starts at 1 and counts up like most modern cameras. After loading film and closing the door, advance the film two frames to get to the first frame, and then lift up on the film lock release lever, which is a little metal piece on the back of the camera to the right of the viewfinder. Behind this metal lever will be a gear that slightly sticks out from inside of the camera. This gear is used to manually advance the frame counter. While holding up the metal lever, turn the metal gear until the counter is set to frame 1, and then let the metal lever fall back into its original position.

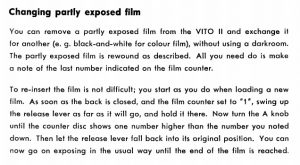

This little metal lever has a variety of uses. When this lever is in its full upright position, the film interlock is disabled which allows you to do a couple of things. The most common is when you reach the end of the roll and need to rewind the film. Lift and hold this lever to its full upright position and you can rewind the film back into its canister. Another use is if you want to double expose on the same frame of film. Lift this lever to its full upright position, and then immediately put it back down and you can now cock and fire the shutter without advancing the film. A third use which is described in the manual is if you want to load a partially used roll of film into the camera mid roll. You must know how many frames of film have already been exposed on a partial roll, but install it into the camera, and by lifting this lever, you can continually advance the film however many frames are needed to get the film to the first unused frame. I doubt this was done very often, but it is an interesting feature that isn’t advertised often on most cameras.

Once film is in the camera and the frame counter has been set to ‘1’, the camera is ready for action. The Vito II shoots similarly to other scale focus folding cameras from the 1950s with one exception which is the location of the shutter release. Unlike other cameras where the shutter release is either on the top plate or the shutter itself, the Vito II has a unique shutter release on top of the door. While at first, this might seem like a strange location to put a shutter release, it works surprisingly well.

For one, by putting the release button farther forward, it is located in a much more natural position for your index finger than had it been on the top plate. I’ve found that when holding small cameras, my wrists tend to turn outwards away from my face. When the shutter release is on top of the camera, I have to bend my wrists into a more upright position for my finger to locate the top shutter release. Whenever a shutter release is farther forward, my wrists don’t need to bend as much. This concept applies to modern digital cameras, specifically DSLRs. Look at where the shutter release button is often found on these cameras. Usually forward on the right hand grip, not the top plate. For such a small camera, I really think that by putting the shutter release on the door makes it much more comfortable to hold and shoot with.

Another reason for locating the shutter release on the door could have been a practical one as well. Any time you have a folding camera with a top plate shutter release, there has to be a convoluted series of linkages and levers and pivot points to make it all work, but still be bendable when the door closes. This complex linkage is a common failure point on many Kodak Retinas and other similar cameras because it can become damaged if the user does not close the door properly. When the shutter release is on the door, the linkage is much simpler, necessitating less parts. Not only does this result in a lower cost to manufacture, it also improves reliability as there are less parts to break.

The next step in shooting with the VIto II is to manually cock the shutter. This is the one and only way in which this camera is inferior to some Kodak Retinas. Starting in 1951, the Kodak Retina 1a Type 015 had an auto cocking shutter that did not require the extra step of having to cock the shutter manually. The earlier Retina I Type 013 would have still had a manual cocking lever. Since the Vito II was in production from 1949 – 1954, it would have spanned both of these Retinas. Even the Vito II’s eventual replacement, the Vito IIa which came out in 1955, still had a manual cocking lever. While not hard to do, it is something that you have to remember to do before each exposure. The rest of the process of focusing, setting a shutter speed, and selecting an appropriate aperture value is pretty straightforward and comparable to the Retina and all other cameras of the era. The Vito II came with both a Prontor shutter with speeds from 1 to 1/300 seconds and it could also be had with a Compur shutter with a top speed of 1/500. Although the Compur could be seen as the ‘better’ shutter, it lacked a self timer which the Prontor shutter had.

The Vito II’s manual has a page devoted to two icons that are in the focus scale specifically for candid snapshots. While any manual focus camera can be used in this manner, the Vito II really spells it out for you, and this was a feature I tried myself while going through my first inaugural roll.

When shooting with any scale focus camera, you normally need to spend quite a bit of time composing your shot and estimating distances between you and your subject. This slows down the process of shooting a photograph and can cause difficulty when trying to take spontaneous, or candid shots where you don’t have enough time to stand there estimating distances.

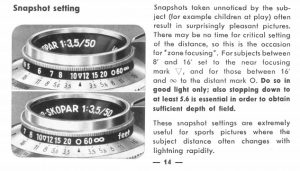

Looking at the focus scale on the Vito II’s lens, you see two icons, a triangle between 10 and 12 feet (or 3 and 4 meters if your camera has a metric scale), and a circle between 20 and 60 feet (or 7 and 20 meters).

The triangle represents a typical portrait distance where someone is approximately 8 to 16 feet away and the circle represents objects beyond 16 feet which would be anything somewhat far away, but not quite infinity. I found the circle setting to be more useful as this is the distance that you are more likely to be away from a moving object such as a child, animal, or athlete. In order to use either of these distances, you must use an aperture size of no larger than f/5.6, but between f/8 and f/11 work best. Since the aperture is small, this works best when your subject is in a well lit area such as outside in the middle of the day. It doesn’t have to be glaring sunlight, but any situation brighter than most interior lighting situations would allow for.

Without getting too technical, the idea here is that at these settings, when you use an appropriately small aperture, you maximize the depth of field, which is the virtual distance between the camera and the subject where everything is in focus. Using the circle setting means that anything from 16 feet to infinity will be in focus. Street photographers will use the term ‘zone focus’ to mean this same thing. Essentially, you are maximizing the depth of field of a set focal distance where you can reliably predict what will and will not be in focus. As long as your subject is within this ‘zone’ it will be sharply in focus. This is the same exact principle used on “fixed focus” cameras like box cameras or toy cameras where everything beyond 8 feet to infinity is always in focus.

If you already understand how zone focusing and depth of field works, I don’t need to explain any further, but even if you don’t quite get it, dont worry too much about it. Just trust me. Set the camera to f/8 or f/11 in a well lit area, turn the focus knob to the circle position and shoot things 20 or so feet away from you and they’ll always be in focus. As I said earlier, this is something all cameras can do, you just need to know where that camera’s sweet spot is, the Vito II just makes it easy for you.

Once you are done shooting with the Vito II, its time to close it. Unlike the Retina, the Vito II does not require the focus to be set to infinity before closing the camera. Merely press down on the two tabs on the underside of the front door and the door easily closes. Each of these tabs is supposed to have a black plastic cap on the tips of them, but sadly on my example, one of the tips is missing. This is just a cosmetic issue and does not impact functionality of the camera.

The biggest part of the appeal of the Vito II for me is that it adds up to more than the sum of its parts. On paper, everything I’ve told you sounds pretty typical of a folding camera from the 1950s. While sure, the shutter release might be more reliable than that of a Retina, but it doesn’t have the auto cocking shutter of the later Retina Ia, so wouldn’t this camera at least be equal to the Retina? I won’t get into which camera is better, the Vito II or the Retina Ia, because they’re both great cameras, but I will say that for the people who hold every Retina camera in high esteem (rightfully so), the Vito II is every bit as good of a camera as the Retina series.

The fit and finish of the camera is superb. All of the moving parts move smoothly and purposefully. All of the moving parts and the turning gears have a jewel-like mechanical sound to them. This camera predates plastic, so everything inside of that beautiful body is metal and it feels like it. The Vito II is truly a wonderful camera.

My Results

This Voigtländer Vito II came to me in excellent condition. I could see the shutter was working fine and the glass was mostly clean. After a quick wipe down of the lens, I felt pretty good that the camera would deliver a result consistent of what this model is capable of. The Color-Skopar lens is highly regarded as being every bit as good as the Schneider lenses found in most Kodak Retinas. I put in a fresh roll of FujiColor 200 because I had learned my lesson on some recent cameras where I put expired film in a camera I wasn’t familiar with and got poor results. I brought the camera with me to work on a bright and sunny day where I went through a majority of the roll.

Sometimes when I get back an inaugural roll of film from a new camera, I don’t know what to expect, but this time my expectations were pretty high. If the Vito II didn’t deliver sharp and nicely rendered shots, it would fail as a suitable competitor to the Kodak Retina. I had no idea if the shutter was accurate, or if there would be light leaks, or if the film plane was perfectly in line with the focal plane. All of these were questions I did not have the answer to until I got the film back.

One more thing I want to say is that this roll was sent in a batch to a new lab. Instead of using Dwayne’s Photo in Parsons, KS like I usually do, I tried Willlow Photo Lab in Willow Springs, MO. This lab advertises their services on eBay for what amounts to a little over $4 a roll, including return shipping, for C41 processing and scanning. The price is less than half of what Dwayne’s Photo charges, but would they do a good job?

Looking through this inaugural roll, I was ecstatic with the results. Does the Voigtländer Vito II compare favorably to a comparable Kodak Retina? The answer is a resounding YES!

Despite being a scale focus camera, nearly every shot was sharply in focus. Using the zone focus method mentioned earlier in this article worked masterfully. I had no trouble getting a moving train in focus, and low light interior shots were sharp and nicely rendered. While the fresh roll of FujiColor film gets a lot of the credit for the nice and natural outdoor colors, the coated Color-Skopar lens deserves some of that credit as well. The lens is sharp across the entire frame. There was no noticeable softness or vignetting in the corners and I saw no chromatic aberrations in contrasty areas.

The camera is all metal and feels solid, with no creaks or groans in your hands. It is comfortable to hold and despite the period correct small viewfinder, I had no problems seeing the entire frame wearing prescription glasses. Despite not having a wind lever, winding the film was easy and uneventful due to the large diameter knob. The film transport was very smooth, as were all movements of the focus, aperture, and shutter speed ring. While I’ll acknowledge that a different camera in less than perfect condition might not exhibit such precision movements, I have to believe that the high quality standards of this camera are responsible for its continued excellence nearly 65 years after it was made.

Amazingly, in this inaugural roll of film through a camera I had never used, I managed to capture two of my favorite images that I’ve shot with any camera. The one of me in the broken mirror and the one of the torn curtains in the abandoned house are haunting. I stare at these images in disbelief that not only are they exposed correctly, but I got them both sharply in focus. The one of me in the mirror was especially difficult because that mirror was in a hallway where I was leaning against the other wall and I had to estimate distance from me to the mirror, then double it, so I would be in focus, and not the mirror itself.

It is probably pretty clear at this point to say that I truly loved my experience with the Vito and look forward to using it again. Sometimes you enjoy a particular camera, but are less than impressed with the results, and then there’s others where the camera’s strengths are not revealed until after seeing its results, but with the Vito II, both were true. This is a beautifully designed camera that was a pleasure to use and it turned out really great photographs.

My Final WordHow these ratings work |

I keep comparing the Vito II to the Kodak Retina, mainly because it would have been the most logical competitor, but I probably should give the Vito more credit. This is not a model that should stand in the shadows of the Retina or any other camera. The Voigtländer Vito II is an excellent instrument all around, and does not need to be compared to anything. It is a compact camera that when folded, easily fits into a front jeans pocket, the shutter release is in an excellent position, the controls are easy to reach, and the lens is as good as anything else out there. I was blown away at the images I received from it and its ease of use meant that almost every single frame from my first roll came out sharply in focus and properly exposed. I thoroughly enjoyed using this camera and cannot wait to take it out again. These cameras often go for less money than an equivalent Retina, and that is great because it means anyone can pick up one of these at bargain prices | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 30% | |

| Bonus | +1 for its compact size, great ergonomics, excellent fit and finish, and spectacular Color-Skopar lens. | ||||||

| Final Score | 11.4 | ||||||

Additional Resources

http://camerapedia.wikia.com/wiki/Voigtl%C3%A4nder_Vito_II

http://mattsclassiccameras.com/vito_ii.html

https://johns-old-cameras.blogspot.co.uk/2011/09/voigtlander-vito-ii.html

https://blog.jimgrey.net/2015/10/28/voigtlander-vito-ii/

Hi Mike,

this is a nice write up of the Vito II. I will just chime in about the Vito I, since some of the information you mention seems to be popping up here and there online and I am afraid it might confuse people.

I have owned two Vito 1 – an early one with hinged yellow filter (lens SN 24XXXX points to production between 37 and 42, probably around 1940) – this one was build to accommodate 135 film, and I am under the suspicion, that all of them were (I saw 3 early Vito 1 in person and more online, and all of them were fitted with the 135 film gate). I believe that just the prototypes were designed for 828 film, not the serial production.

The late one (lens SN 27XXXX which seems to be from 1945) has subtle differences, otherwise it is pretty much the prewar model.

I know the lens serial numbers might be misleading, because it is not unheard of to use older lenses when building new cameras, but I think that specifically this Skopar was produced at that time only for Vito 1 – so the production probably restarted right away in 1945 or 1946.

Thanks for another nice review, and I hope you get a hand with the Vito 1 as well, they are nice cameras (except for the viewfinder that is 🙂 )

Jan

Great article Mike. Really interesting and informative. Thanks for your efforts and those are some great shots you got there. I especially like the curtain blowing in the window and the red peeling paint shots. Kind regards…Paul.

Thanks Paul. The one of the curtain flowing is one of my favorites too. That is a dilapidated house near my work and I went in through the front door, turned to my left and saw that window. I was impressed to nail focus and exposure on my very first roll through the Vito!

I found your article from July 2016 on the Voightlander Vito II camera with the lens that closes. My father recently passed away a couple of weeks ago, and he still had this type of camera which was given to him by his brother Darrell, who bought it when he was stationed in Germany in the 1950s. My guess is that this camera is at least 60 years old. It is now in my possession. I believe the last time that we used it was on vacation in 1978 when we went to Yellowstone National Park. I was only 11 years old. I used 35mm slide film in the camera at the time, and it took very good pictures then.

I plan on testing this camera. I haven’t purchased film in many years as my own family has owned digital cameras for some time. My friend who is ready to retire from teaching is a photographer from way back and is going to teach me about the various settings. I also downloaded the original manual which I found online. I wanted to thank you for the information and pictures you posted. We seem to have the exact same model. I look forward to using this again. My only question is what it is worth in such good working condition. The original case, of course, rotted away years ago. The leather dried out and it crumbled. Wouldn’t it be great to find a case that fit it just like the original?

Thanks for your time and your article.

Hello Mike,

I’m surprised that I came to your wonderful article so late. Over the years, I bought three Vito 0 cameras (1940-41) and recovered two of them. This is my favorite analog camera. Skopar 50mm F / 3.5 is a very sharp lens, and because this version has no coating, transmits colors uniquely.

In Bulgaria, this camera is not so rare, because during WW2 several hundred were imported here and some of them have survived. Still can be found on some flea market 🙂

Mike,

I just acquired a Vito II in excellent condition, and today developed and scanned the first roll I’ve put through it. Fomapan 100, my first roll of that as well. Camera and film worked well together, the instrument is a pleasure to hold and use. And I’m very pleased with the resulting images. Much more fun to use than my Kodak 35RF and I think the pictures are more sharp than my Signet 35. Don’t have a Retina against which to compare it…..now I doubt i need one.

Hello Mike. First off, kudos to you on a thoroughly informative post. It sure answered a lot of questions I had about the Vito II a (similar to the Vito II) I have. I was wondering if you could point me in the right direction regarding the manual shutter cock on these cameras. You see, I took a B&W roll out for my very first shoot. All went well (I dutifully remembered to manually cock the shutter before each exposure). For some reason, the manual shutter cock no longer slides up as it used to. I’m looking for a repair manual that might help me fix it. Do yu have any suggestions? Thanks again for the great post! Best regards, Dave.