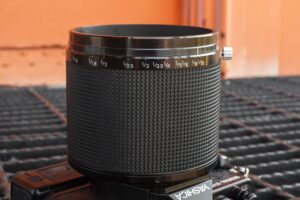

This is a Yashica Dental-Eye, a 35mm SLR camera made by Kyocera starting in 1985. The Dental-Eye, as the name suggests, is a specialized camera produced primarily for the dental industry allowing for extreme closeups, but it was also used by eye doctors and in other specialized medical and scientific industries where an easy to use close-up camera was required. The Dental-Eye is a modified Yashica FX-3 with a fixed 55mm f/4 macro lens and a built in electronic ring light. The shutter is fixed at 1/60 and instead of the ability to focus, a large “focus-like” ring sets the magnification ratio from 1:1 to 1:10. The lens is optimized for macro photography only and cannot focus to infinity, making the Dental-Eye impractical for general use. Despite the camera’s purpose built limitations, the Dental-Eye was a success, spawning two follow up models which remained in production until 2006.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 55mm f/4 Yashica Lens coated 4-elements in 3-groups

Focus: Magnification Ratios 1:1 to 1:10 (approximately 7.9 cm/3.1 inches to 58.1cm/22.9 inches)

Viewfinder: Fixed SLR Pentaprism, 92% Field of View, 0.91x Magnification

Shutter: Vertically Traveling Metal Focal Plane

Speeds: 1/60

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: (4x) 1.5v AA Alkaline or Rechargeable Battery

Flash Mount: Hot Shoe and Electronic Flash Ring

Other Features: Illumination Light

Weight: 1170 grams (with batteries)

Manual: https://mikeeckman.com/media/YashicaDentalEyeManual.pdf

How these ratings work |

The blah blah blah | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0% | |

| Bonus | +1 for unique feature set that few cameras have | ||||||

| Final Score | 10.0 | ||||||

History

Photography has many uses. In addition to vacation photos, family portraits, and mirror selfies, astronauts have taken cameras into space, police officers have photographed crime scenes, and doctors have used them to take photos of various medical procedures. One specific subset of medical photography is dental photography in which a dentist can take a photo inside of someone’s mount to get a better look at an area of the body that is not easy to see.

The challenge with dental photography is two fold, for one, you have to find a way to fit a bulky camera inside of a human mouth to capture tiny details in people’s teeth, but also you need to find a way to properly expose the image so that poorly lit areas of incisors and molars are easy to see.

I was not able to find much information online or in printed resources regarding medical photography, but I suspect a large number of third party companies made various accessories such as extension tubes, bellows, attachments, special flashes, and other brackets for extreme close up photography.

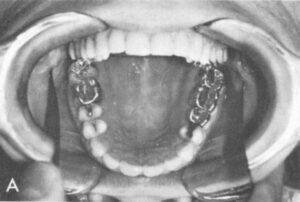

A simple kit for macro photography might have looked like the Ihagee Exakta to the left which is fitted with a Steinheil macro lens and a ring flash attached to the front of the lens. This type of kit would have allowed for a 1:1 magnification ratio and an even distribution of light for eliminating shadows. Since the Exakta is an SLR, the photographer would have been able to compose and focus exactly what he or she wanted to capture, and then upon pressing the shutter release, capture a closeup that might have looked like the image to the right.

While this sounds simple enough, I suspect a challenge existed in that dentists and other medical professionals are usually not photographers, and photographers are usually not dentists. To put a kit like this together, most dentists wouldn’t have been able to stroll down to the local camera store and put together a specialized kit that met their needs exactly.

I suspect that for most of the 20th century, “dental” cameras were just off the shelf cameras with some kind of hodge podge of accessories assembled together to meet, as closely as possible, the needs of the user. The first evidence I could find where someone offered a purpose designed kit came in the late 1960s by a company named Tokyo Shizaisha out of Japan.

Tokyo Shizaisha is a dental supply company founded in 1961 by Ichiro Yoshida and aimed to supply the dental industry with a large variety of dental accessories and equipment. While not specifically an optics company, there was clearly a need as in 1968, the company began offering their own version of a modified Yashica rangefinder camera called the Yashica Oral-Eye. That the camera is branded still with the Yashica name and has official looking modifications suggests that Tokyo Shizaisha worked directly with Yashica to put out this camera, rather than simply taking cameras off the shelf and modifying them in the aftermarket.

The Oral-Eye came in a kit with a heavily modified Yashica Electro 35 GT with a fixed 55mm f/4 macro lens fitted with an electronic ring light around the perimeter of the front of the lens. Since the Oral-Eye is based on a rangefinder and not an SLR, TTL composition was not possible and since macro photography on a rangefinder is notoriously difficult, within the kit were assorted brackets and external frames which when attached to the bottom of the camera, offered the user a precise way of measuring the correct magnification ratios and focus distances. In addition to these pieces, the camera also came with an external grip for better handling, and the entire kit came in a black carrying case.

I found no pricing or production numbers for the Oral-Eye, but that it was a niche product for an underserved segment, my best guess is the Oral-Eye sold well enough in the market it was intended, at least well enough to support a line of dental SLRs from Yashica in the 1980s and 1990s. It would take over a decade and a half, but in 1985, an all new camera sold by Yashica was released called the Yashica Dental-Eye. Built in house by Yashica’s parent company Kyocera, the Dental-Eye appears to have still been distributed by Tokyo Shizaisha, but unlike with the Oral-Eye, that company’s name does not appear anywhere on the camera itself, or in the original user’s manual.

The Dental-Eye was based off the existing Yashica FX-3 SLR from 1979 and had a permanently mounted FX-D motor drive chassis which lacked the actual motor drive parts, and only served as the camera and flash’s battery compartment. Like the Oral-Eye, the lens was a 55mm f/4 macro lens with an electronic ring light. New to the Dental-Eye was an illumination bulb which could be turned on separately from the main flash, to help with image composition through the somewhat dark pentaprism viewfinder. Apart from the lens, flash, and motor drive battery compartment, another change from a regular FX-3 was that the shutter had a single 1/60 speed and could automatically expose images based on chosen film speed and magnification ratio selected on the lens. Early versions of the camera still had the original FX-3 model number, but this was quickly changed to Dental-Eye at some point.

The Dental-Eye was updated twice, the first was in 1990 as the Dental-Eye II and again in 1997 as the Dental-Eye III. Each subsequent version of the Dental-Eye was based on newer Kyocera produced SLRs, the Yashica 107 MP and the Contax RX respectively. Both the Dental-Eye II and III replaced the original 55mm f/4 macro lens with a 100mm version which is said to have been done to address complaints that the 55mm lens required the camera to be uncomfortably close to the patient while in use. With the longer lens, a little more distance kept the camera from getting too close, but also increased the minimum magnification ratio to 1:15. A few variants of the Dental-Eye II and Dental-Eye III exist as the Yashica Medical 100 and other versions were sold with Kyocera, rather than Yashica branding.

Beyond what I could learn by looking at images of the Oral-Eye and then other Dental-Eyes, there is very little information about them online or in printed media. I found absolutely no marketing or promotional material about them, nothing about production numbers, or what they might have sold for. I did find several mentions of the Dental-Eye in back of magazine ads for camera stores on Google Books, but in every instance where the Dental-Eye is mentioned, the price is listed as $CALL. A thread on a Yashica forum from late 2019 was the best source of information I could find as it uncovers some facts about the camera, but the people participating in that discussion ran into the same dead ends as I.

The Contax RX was produced until the early 2000s, so it stands to reason that is when new supplies of the Dental-Eye III would have dried up and with the rise of the digital camera era, no new dental cameras were produced by Yashica or Kyocera. I suspect that with the affordability of compact digital cameras like the MouthWatch Intraoral Dental Camera System available today for as little as $299, the need for a large and bulky SLR based dental cameras no longer exist.

Today, these cameras aren’t discussed much in camera collecting circles, which I find strange as their design is actually quite good. People still like taking close up shots and there are thriving online communities dedicated to macro photography. Perhaps the name “Dental” in the camera’s name has caused people to mistakenly assume that it can’t be used for taking close up pictures of other things. Whether you are a dentist with a penchant for film, or just like taking pics of flowers and bugs, the Dental-Eye is worth considering, and that they’re still relatively “young” film cameras, made by a capable manufacturer, suggests that most should still be in good working order today.

My Thoughts

Of all the cameras reviewed here on mikeeckman.com, every single model I’ve shared with you was specifically designed for general photography. Whether it is a professional SLR like the Nikon F, or a twin lens reflex like the Rolleiflex, each of these cameras were made to take photographs of every day objects. Never in the history of this site have I reviewed a camera that was not made for general photography, but rather, a very specific type of photography.

Today’s review of the Yashica Dental-Eye is one such camera, which as the name suggests, was created for dentists to take photos of things dentists love, teeth! Now, to be fair, people outside of the dental industry did use these cameras, as the Dental-Eye can be useful in other industries which need to take high quality photographs of very small things. People who study bugs, flowers, and other micro sized objects may have had a Dental-Eye in their camera bag, but considering the Dental-Eye is most associated with dentists, we’ll just say this is my first ever dental camera.

The Yashica Dental-Eye was the first SLR made for dental applications by Kyocera, owner of the Yashica brand and is based on the Yashica FX-3 first introduced in 1979. The camera shares much of the same body as the FX-3 but without the ability to control shutter speeds. Instead, the shutter is a fixed 1/60th of a second, and the auto exposure system controls the aperture of the large macro lens permanently mounted to the camera. Although originally an interchangeable lens SLR, the Dental-Eye’s lens cannot be removed. An electronic ring light circles the circumference of the front lens grouping and a small Illumination Light is at the top of the flash to aide in framing your image in low light.

When sold, the Dental-Eye came in a black leatherette case which protects the camera when not in use. A quick look at used examples of this for sale online, a large number of them are found still inside the original case. I suspect that due to the specialised use of these cameras by dentists, the camera was rarely separated from its case and often put back in after each use. An interesting characteristic of this particular Dental-Eye is that the inside of the case actually smells like a dentist office! I am not sure exactly what it is, but even without knowing this camera likely spent a decade or more inside a dental office, a quick whiff of the camera and case make me think of my own dentist.

The Dental-Eye came to me in fully functioning condition and had otherwise good cosmetics except for one glaring fault, which was the leatherette body covering which was disintegrating on every surface. Simply picking the camera up, and sticky black dust came off on my fingers, adhering to anything it touched. This issue with disintegrating body covering isn’t unique to the Dental-Eye as the original FX-3 has the same problem, suggesting that whatever material Kyocera was using back then was at fault. Premade kits can be purchased online to replace the sticky body covering of a Yashica FX-3, but sadly, none exist that I could find for the Dental-Eye. While the body of the two cameras are the same, looking at images of the Dental-Eye and an FX-3, I suspect only the piece on the film door would be the same as the surfaces of the front, sides, and additional battery pack are unique to the Dental-Eye. I suspect that any attempt to recover this camera would require someone to hand cut from bulk leather, which is a task I was not interested in attempting.

Aside from the disintegrating body covering, the Dental-Eye has good build quality which unsurprisingly is on par with other late 1970s / early 1980s Yashica SLRs. The addition of the large lens and permanently mounted battery pack did not decrease the feel of the camera, although it does contribute to its weight. At 1170 grams, the Dental-Eye is not a lightweight camera, and although there would be no reason to keep it around your neck for a long shooting session, its heft would very much be noticeable if you ever attempted to do so.

Up top, the Dental-Eye resembles a standard SLR with the rewind knob and fold out handle on the left, the fixed prism has what looks to be a standard flash hot shoe on top, but in reality this shoe was never intended to be used with a flash as the camera’s metering system was only designed to work with the build in ring light. Adding an external speed light or other flash would almost certainly overexpose every image you shot with it. Instead, the flash shoe was repurposed to power an optional data back which was available for the camera. To use the data back, you’d replace the original door with the new back and you could record exposure information, magnification ratio, and a time stamp onto each exposure. I did not have the data back for this review, but for fun, I tried to mount a couple electronic speed lights I had, and none fit.

To the right of the prism is a knob which on the original FX-3, controlled shutter speeds, but here is the ISO film speed selector since the Dental-Eye has only a single 1/60 shutter speed. With only 6 options from ISO 64 to 1000, this dial can be used as a sort of EV compensation if you were motivated enough to try to do the math in your head. Above and to the right of the film speed dial is the shutter release in the standard location, The shutter release is threaded for a cable release, but due to only having a single shutter speed and that this camera is macro only, I can’t really see a use to use a cable release. Next is the automatic resetting exposure counter and film advance lever.

Permanently grafted onto the base of the camera is a modified motor drive unit for the FX3. I say modified as the motor drive housing used on the Dental-Eye doesn’t actually have the parts for the motor drive in it. It is only used as an external battery compartment that powers camera and the ring light. Four AAA batteries slide into the same location as the original motor drive, with a 1/4″ tripod socket on the bottom but nothing else.

There is little to see on the sides of the camera, as there are no flash sync ports or any kind of door release on the side of the body. On the left side of the motor drive unit is the cover for the actual battery compartment. The Dental-Eye has front angled metal strap lugs for attaching a neck strap. While the Dental-Eye wouldn’t have been used on a leisurely walk through a park, I suppose dentists might have still used a strap to allow the camera to dangle from their neck in between exposures with their patients.

Around back, the main part of the camera looks the most like the FX3 as any other part, with the rectangular eyepiece for the viewfinder above the film door. The piece of body covering on this camera is in terrible condition, constantly crumbling and leaving a sticky black powder on everything this camera touches. While a macro only camera already has a limited use as something I’d shoot over and over, if I ever wanted to shoot this camera more than just for this test, I’d definitely want to figure out a solution to replace the body covering as touching this thing is nasty. The back of the motor drive housing has a power LED, power switch, and a combined rewind release button and lever. Since you cannot access the normal rewind release on the base of the body, you must use the one here to rewind your film at the end of a roll.

Opening the film door requires you to lift up on the rewind knob on top of the camera and give it a swift tug to release the lock. The right hinged door swings open to reveal an ordinary SLR film compartment. Film transports from left to right onto a nonremovable multi-slotted plastic take up spool. Since it is based on a camera from 1979, the Dental-Eye lacks the contacts for DX film encoding and does not have any sort of quick load system. Two set of polished film rails are above and below the film gate. Inside the film door is a large metal pressure plate covered in small divots which help reduce friction as film passes over it, Amazingly, despite the entire camera being covered in a material that was disintegrating, the foam light seals on this camera were in remarkably good condition. I still would advise replacing them for someone who planned on shooting this camera more than once, but for a single test roll, they looked to be in good enough condition.

Looking down upon the top of the large macro lens, there’s little to see other than the magnification ratio markings on the front edge of the lens. The entire rest of the barrel is covered in a thick rubber grip which is very easy to turn. The permanently mounted macro lens does not indicate focus distance, rather magnification ratios of 1/1 to 1/10. As the name suggests, this changes the size of the exposed image. The closer to 1/1, the more magnified the image is.

Focusing the lens is done by moving the camera backward and forward until the image comes into focus. This is a little strange for someone not used to macro photography, but this is how its done, and even for those not familiar with the process, it is pretty easy to figure out once you have the camera to your eye. In essence, turn the barrel until the image is the size you want in your viewfinder, and then move the camera until it is in focus. With the lens at the lowest magnification ratio or 1/10, you can focus images as far away as almost 2 feet.

The viewfinder is very simple and reasonably bright. I believe a normal FX-3’s viewfinder has the potential to be brighter with a faster lens, but with the maximum aperture of the macro lens being a relatively small f/4, you’re not going to get as much light through the prism as you would with an f/1.4 lens. The focusing screen has a microprism circle in the center with a ground glass collar around it for precision focus. While I normally prefer split image focus aides on manual focus SLRs, for the purpose of close up photography, I actually prefer the microprism collar as I find it easier to “see focus”. There is nothing about exposure visible inside the viewfinder, only a single flash ready LED which indicates the electronic ring flash is charged up and ready to fire. I did notice a strange softness near the bottom edge of the viewing screen, almost as if something was obstructing the light entering the prism. I thought perhaps the lens was actually seeing the inside of the ring light, but upon changing magnification ratios to where this isn’t happening, the softness was still there. This didn’t appear in any of my images however, so it must have been a characteristic of how the viewfinder is designed. This being the only Dental-Eye I’ve handled, I am unsure if this is normal or unique to this specific example. If anyone knows, let me know in the comments below.

Without having ever used a Dental-Eye before, I can already see the appeal of an SLR based camera with a fixed macro lens and proprietary ring light setup. This was a camera designed for dentists, not photographers, so convenience and ease of use was clearly the priority and from what I could see while handling it, it seems like it would do a good job. Of course, the only way to find out for sure is to go to dental school, load it up with some film, and take it out shooting. Okay, maybe I skipped that first part, but I did the next two…

My Results

Disintegrating sticky body aside, the Yashica Dental-Eye was in great condition when I picked it up and everything, including the flash and illumination light appeared to be in working condition. In addition, when the Dental-Eye’s turn in the queue came up, the area in which I live was experiencing the emergence of a periodical cicada called the Magicicada Septendecim which happens only once every 17 years. These bugs are very loud and annoying, but quite beautiful and would be an excellent subject to shoot macro photographs of! I loaded in a fresh roll of Fuji 200 and took the Yashica Cicada-Eye out shooting!

I never could find out for sure, but I believe the lens used in the Yashica Dental-Eye is the same as the Yashica ML Macro 55mm f/4 lens which the company made around the same time in the C/Y mount. Considering the very specific use of the Dental-Eye, this wasn’t a camera that likely was going to sell a ton of copies of, so it would make sense that Kyocera would have used as many off the shelf parts as they could in building it.

The images from my test roll were quite good, with excellent sharpness and an overall pleasing look. I did blow out the highlights in some of the teeth photos, and color accuracy was a bit off indoors, but I attribute that more to how I developed the film. I was using a C41 Unicolor kit that was nearing exhaustion, and in hindsight, should have been replaced. One characteristic of a macro lens is that they are designed to capture as flat of a field as possible, so they often have extremely smooth and indistinct out of focus details. If you’re looking for swirly or soap bubble bokeh, this isn’t the lens for you, but that’s not the intent of the lens anyway.

I found the images from this camera to be excellent and far beyond what a dentist would have needed to analyze closeup photos of people’s teeth. It is clear the strength in this camera would have been for more detailed and colorful objects like flowers and bugs. I suspect enthusiasts of stamps and other tiny figurines would have enjoyed shooting extreme closeups of their collections with this camera.

Image quality aside, the most impressive thing that the Yashica Dental-Eye does is simplify macro photography to a near point and shoot simplicity, which of course, is kind of the point of this camera. Dentists are not photographers, and while I’m not saying this camera is entirely foolproof, to compose, capture, and illuminate very small objects using a regular camera can sometimes be quite difficult. A ring light is excellent for this style of photography because it illuminates the subject in a 360 degree circle, eliminating unwanted shadows. Flash photography comes with its own challenges when shooting objects 5 feet away, but when shooting something 2 inches away, the challenges are even greater. The closer the light is to the subject, the greater the chance of blowing out the image with light. Margin of error in macro photography is razor thin. Handhold a digital camera with a macro lens and you can compensate by blasting 20 photographs one after another, hoping that at least one of them is right, but with film, it is critical to get the shot right the first time. For there to be a camera that not only allows you to easily compose, focus, and properly expose your image without having to think about everything that can go wrong is the greatest strength of the Dental-Eye, and one reason I think this camera is a compelling option today.

In my research for this camera, I read that this first Dental-Eye was criticized because of its 55mm focal length, dentists would have to get uncomfortably close to their patients, so when Kyocera released the Dental-Eye II, they upgraded the lens to a 100mm version, allowing the user to have a little more space between the camera and subject.

For my purposes, the focal length was not an issue, nor was the maximum 2 foot focus limitation. If I wanted to shoot something more than 2 feet away, I would just use another camera. Beyond that (and the nasty body covering), I have no other criticisms of the Dental-Eye. The limitation of a single shutter speed and no direct control over aperture or exposure is not an issue. The gallery above proves that a first time user of this camera got mostly excellent results from his first roll.

I don’t know how many people reading this will be compelled to run out (or login to eBay) and pick one up of your own, but you should. This is a really fun camera that does something that few other cameras can do, make macro photography fun and incredibly easy! Highly recommended!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Yashica_Dental_Eye

https://www.johnwade.org/dental-eye

https://www.lomography.com/magazine/19173-yashica-dental-eye-no-longer-for-the-teeth

https://yashica.boards.net/thread/611/yashica-dental-eye

https://yashica.boards.net/thread/771/kyocera-yashica-100mm-medical-dental