This is a Zeiss-Ikon Contax III, a 35mm rangefinder camera built by Zeiss-Ikon in Dresden, Germany between the years 1936 and 1942. The Contax III was an upgrade to the Contax II from the same era, adding a selenium exposure meter to the top plate. The Contax II and III are both historically significant cameras, and along with the Leitz Leica helped popularize “miniature” 35mm cameras. The Contax III has an interchangeable lens mount with an inner bayonet for 50mm lenses, and an outer bayonet for all other focal lengths. Contax cameras from this era are some of the most popular and collectible cameras ever made.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 5cm f/1.5 Carl Zeiss Jena uncoated 7-elements

Lens Mount: Contax Double Bayonet

Focus: 0.9 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder

Shutter: Vertically Traveling Metal Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/1250 seconds

Exposure Meter: Uncoupled Selenium Cell

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Weight: 763 (w/ lens), 634 (body only)

Manual: https://www.pacificrimcamera.com/rl/00959/00959.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Zeiss-Ikon Contax III needs no introduction as it’s one of the most historically important cameras ever made. This example was found in barely working condition and although was quite nice to use, couldn’t make it through it’s first roll. These are wonderful examples of German engineering and worthy of adding to any collection, but if you want to actually shoot one, you’ll need to open your wallet and have one repaired. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 40% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 14.0 | ||||||

History

Ford vs Chevy, Windows vs Mac, Coke vs Pepsi, long have there been debates about which of these products was better. For photographers in the early/mid 20th century, an often heated debate was that of Leica vs Contax rangefinders. Both cameras were produced by two of the most respected German optics firms of the 20th century and each represented a huge leap forward in quality and features in the 35mm rangefinder segment. But despite what was a long list of similar features on each camera’s spec sheet, how each camera looked and worked, couldn’t be more different.

Ford vs Chevy, Windows vs Mac, Coke vs Pepsi, long have there been debates about which of these products was better. For photographers in the early/mid 20th century, an often heated debate was that of Leica vs Contax rangefinders. Both cameras were produced by two of the most respected German optics firms of the 20th century and each represented a huge leap forward in quality and features in the 35mm rangefinder segment. But despite what was a long list of similar features on each camera’s spec sheet, how each camera looked and worked, couldn’t be more different.

The lens mounts, shutter, rangefinder, and entire body design was totally different from that of the Leica. About the only thing that the two cameras shared in common was that they both used double perforated 35mm film, and even then, there were differences. Most of the design of what would become Zeiss-Ikon’s first Contax rangefinder is owed to a Zeiss design engineer named Dr. Heinz Küppenbender.

Küppenbender was born in western Germany in 1901, studied at the Technical University of Aachen, graduating with a degree in mechanical engineering in 1924. In September 1927, he joined the firm of Zeiss-Ikon in Dresden, first as an assistant, but later in the research department as he already had a working knowledge of shutters.

While working for Zeiss-Ikon, Küppenbender continued his studies, eventually earning his doctorate in 1929 from the Technical University of Stuttgart. For Zeiss-Ikon, Küppenbender studied the inner workings of the Leitz Leica camera. First released in 1925, based on a prototype from 1913 by former Carl Zeiss employee, Oskar Barnack, the Leica was quickly becoming one of the most popular cameras in Germany. With sales exceeding 60,000 units by 1930, Zeiss-Ikon knew this was a market segment they couldn’t ignore and would need to have their own competing model.

While analyzing the inner workings of the Leica, Küppenbender found it to have many shortcomings to it’s design. Starting with the shutter, which on the Leica traveled horizontally across the 36mm film plane, was made of cloth, and had a top speed of 1/500, was found to be erratic in it’s timings. While traveling horizontally along the longer distance of the frame, the speeds of the curtains had to accelerate at the start of exposure, and rapidly decelerate near the end in order to maintain even exposure, but Küppenbender found there to be a wide range of variances among the different samples he analyzed. Another problem was that due to the cloth material, when the lens was focused to infinity, it effectively acted as a magnifying glass on the shutter material, and if pointed at the sun or any bright light source, could easily burn a hole in the material which would require replacement of the curtains.

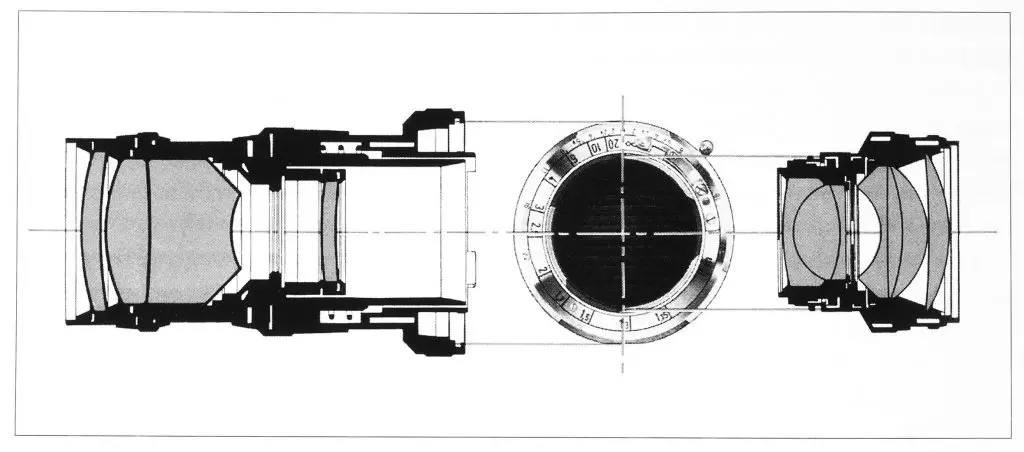

To overcome these obstacles, Küppenbender designed a vertically traveling metal shutter that not only solved the problem of burning holes in the curtains, but by rotating the shutter 90 degrees from that of the Leica, the shutter only had to travel a shorter 24mm distance, meaning that more precise timings and a top 1/1000 shutter speed would be possible.

Another area that received significant attention was the rangefinder. The Leica used two separate windows, one for the coupled rangefinder, and the other for the main viewfinder. The two windows were about an inch apart, slowing the photographer down when he or she had to move their eye between the two windows. For his new camera, Küppenbender wanted the two windows to be as close together as possible.

Yet another perceived shortcoming of Leitz’s design was that Leica rangefinders used mirrors that were cemented to arms that were coupled to the lens via an arm with a wheel on the end. While creating a new rangefinder, Küppenbender found that cementing small mirrors to a metal plate like the Leica used was more difficult than he had imagined. For one, getting a cement that could handle small bumps to the camera without having the mirrors break off, while also being able to be applied thin enough so as not to cause a measurement error from the hardened cement between the back of the mirror and it’s plate was a challenge. To overcome this obstacle, rather than use mirrors, Küppenbender created a rotating wedge prism that used a solid piece of glass that rotated on a central axis directly connected to the focusing helix. This had the combined benefits of a perfectly reflected rangefinder image, it would never fall off if the camera was dropped, and it eliminated any error caused by the cement holding the mirror in position.

As with the Leica Model C, Zeiss-Ikon wanted their new camera to have an interchangeable lens mount, but they found that the screw mount was not only slower to put on and take off, but that the screw threads could be damaged by mounting the lens incorrectly, and the exposed focusing arm of Leitz lenses could be damaged if mishandled. As a result, an all new bayonet lens mount was created that not only was faster to take on and off, but kept all the focusing parts within the lens mount itself, at least for 50mm lenses. While superior in speed and reliability, the internal Contax mount would only work for lenses of a single focal length. In order to mount anything other than a 50mm lens, the pitch of the internal helix would be incorrect, which required a second, external bayonet to be used with lenses that had their own helix which not only added complexity to the lenses, but increased their cost.

The final area of attention that Küppenbender considered was the manner in which film was loaded. When Oskar Barnack created the first Leica, he prioritized body rigidity and the ability to keep unwanted light out of the film compartment, so he went with a bottom loading design in which both the take up and supply spools came out of the camera, the film was loaded and then slid in through the bottom of the camera. Although effective at keeping light leaks out, this method was slow and clunky, requiring 5 full pages explaining how to load film into the Leica Model A’s user manual. Another shortcoming of the bottom loading design was that since the photographer would never have access to the film compartment, it was difficult to inspect the shutter or clean broken pieces of film that often fell off as film transported through a camera.

To solve all of these problems, Küppenbender created a back loading design in which the entire back and bottom of the camera came off at once, revealing the entire film compartment. This not only sped up loading of film into the camera, but solved the issue of being able to clean broken chips of film out of the film compartment.

Of course, at the time when both the Leica and new Zeiss-Ikon camera were being built, there was no universal standard for daylight loading 35mm film cassettes. For both cameras, photographers would need to either bulk load their own 35mm cinema film, or acquire special cassettes developed for each camera.

Leitz’s system was simpler, still requiring a special supply cassette, but winding onto a take up spool in the camera, which would then be rewound back into the supply cassette at the end of each roll. Zeiss-Ikon created special cassettes that would use a cassette to cassette transport that didn’t require any rewinding at the end of the roll. While a cassette to cassette transport has some advantages, Leitz’s system proved to be more popular and in 1934 when the Eastman Kodak Company would create their new type 135 format cassette, they based it off Leitz’s method.

The last challenge for Zeiss-Ikon’s new camera was what to call it. For that, they created a contest among their own employees to come up with a name. The name “Contax” was decided upon and for his or her winning suggestion, an unnamed employee received a prize of 5 Marks.

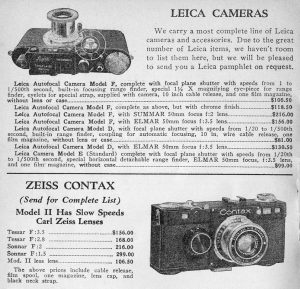

The Zeiss-Ikon Contax made it’s debut in 1932 with a lot of ground to make up if they wanted to match the Leica’s soaring popularity. The Contax was an extremely complicated camera with specs and technologies in it that the camera world had never seen before. While impressive on paper, the Contax was also very expensive. In their 1935 catalog, Central Camera in Chicago sold the Leica Model D (today called the Leica II) with f/3.5 Elmar lens for a not insignificant $130.50. The Contax with f/3.5 Tessar was $156 and went up from there. Equipped with the f/2 and f/1.5 Sonnars, the prices jump to $219 and $299 respectively. When adjusted for inflation, these prices compare to $2455 for the f/3.5 Tessar and $5625 for the f/1.5 Sonnar.

If a high price tag wasn’t enough to dissuade potential customers, the Contax was so cutting edge that early examples suffered from poor reliability. Zeiss-Ikon was constantly updating the camera with as many as six distinct variations between 1932 and 1936. Even within those six submodels, there were many more subtle changes made to the inner workings of the camera in an effort to improve it’s reliability. As the camera was improved, many early examples were sent back to the factory to receive upgrades and when this happened, a second date code was stamped into the camera’s top plate indicating both the year the camera was originally made and when it was updated.

The Zeiss-Ikon Contax sold slowly, and perhaps realizing that no amount of subtle updates to the original design would get them anywhere near the Leica’s dominant market share, in 1936 Zeiss-Ikon would reboot the camera with an all new model, simply called the Contax II. For this new camera, Zeiss-Ikon handed the reigns to Hubert Nerwin.

Nerwin, an Austrian citizen was also a mechanical engineer like Küppenbender, but had no formal experience with cameras or photographic shutters prior to joining Zeiss-Ikon in 1932. Originally working in a low level position in the design department, Nerwin quickly rose through the ranks at Zeiss-Ikon due to a combination of internal turnover and his own design skills. Within a short amount of time, Nerwin found himself as the head of the design department and took on the challenge of fixing the Contax’s problems.

Without a lot of time, rather than completely designing a new camera from the ground up and requiring new lenses, the double bayonet lens mount was retained, although with some reliability improvements. The shutter would still be made of metal and travel vertically through the camera, but the whole design was changed, significantly improving it’s reliability and increasing it’s top speed to 1/1250. The rangefinder system would be changed as well, incorporating a single viewfinder window with a combined coincident image coupled rangefinder. Lastly, an all new chrome plated body that weighed less and came with rounded corners and better ergonomics was employed to address the poor handling of the original Contax.

With these improvements, Nerwin had one more trick up his sleeve which was the addition of a second new model, this one featuring a body mounted selenium exposure meter. This metered model would go on sale shortly after the Contax II as the Contax III and would be the first electrically metered 35mm rangefinder camera.

The updated Contax II was a huge improvement over the previous model, but by the time of it’s release, with over 200,000 Leicas already sold, Zeiss-Ikon had a long road towards competing in the premium 35mm rangefinder segment. Adding to this challenge was a large number of competing German built 35mm cameras by Kodak, Certo, and several other companies, plus growing political turmoil in Germany and a looming war, sales of the Contax II and III were still slow.

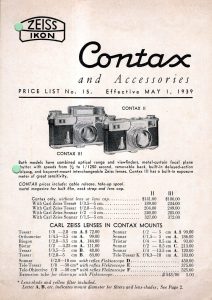

The news wasn’t all bad however, as the improvements to the Contax were not lost on those who purchased it. The convenience of the combined rangefinder, removable film back, and bayonet lens mount won over many professional photographers. Zeiss was also a more respected lens maker than Leitz with it’s Tessar, Biotar, and Sonnar formulas available in a wider range of focal lengths from 28mm all the way to 500mm. In their May 1939 catalog, Zeiss-Ikon featured 15 different lenses in Contax mount and a huge number of accessories and add-ons for macro, scientific, or other specialty work. The huge number of lenses and accessories made them very appealing to professional photographers who needed more than Leitz had to offer.

In addition to all of it’s improvements, Zeiss-Ikon was able to narrow the gap in price between the new Contax and the Leica. In Central Camera’s 1938 catalog, a Leica Model G (today called the Leica IIIa) with a 50mm f/2 Summar was $213 and a Contax II with a 50mm f/2 Sonnar was $233. Prices for different lenses maintained a $20 spread between that of a Leica with comparable lens. The metered Contax III carried a $50 premium regardless of lens chosen. Combined with the additional features and better lens selection, these prices made choosing a Contax over a Leica a much easier proposition than with the previous model. The Contax III with f/1.5 Sonnar I had access to for this article, had a price in 1938 of $370 which when adjusted for inflation is comparable to $6800 today!

Production of the Contax II and III would continue until 1942 at which time all factory output was devoted to the German military effort. Like most other Dresden area camera makers, the ICA factory where the Contax was produced was destroyed during Allied bombing raids in February 1945, leaving almost nothing of the machinery needed to build it behind.

In August and September 1945, with Dresden falling in what would become Soviet controlled East Germany, the Soviet government sought supplies and factory machinery from Zeiss-Ikon as war reparations and had an intention to continue production of the Contax in the Soviet Union. Before this could happen, the Soviet army needed to assess what they had, so what remained of Zeiss-Ikon’s Dresden factories were stripped and sent to Jena where workers there were tasked with restarting production of the Contax. Although Jena had been producing lenses and rangefinders prior to the war, very few people there had the necessary expertise to build a camera, and none knew anything about the Contax.

The responsibility of building the Contax in Jena was largely placed in the hands of two Zeiss engineers, Wolfgang Hahn and Walter Horn. Equipped with schematics for the construction of the camera, the two men started to put together a group of workers in Jena to construct the camera. Many spare parts from before the war still existed, but nothing for the shutter, so shutters had to be completely rebuilt from the ground up.

One day in the fall of 1946, Soviet military officers showed up at the house where Wolfgang Hahn, Walter Horn and their families lived and told them they were being relocated. First, to a town outside of Jena, and then eventually by train to Kyiv, Ukraine where they were told they were going to work at an old arsenal factory, first built in 1764, to produce a Soviet version of the Contax. Upon their arrival at the Arsenal factory, Hahn and Horn were surprised to see that some of the reclaimed equipment from Dresden had been boxed up and transported there. Supplied with floor plans of the Dresden factory, and a team of unskilled peasant Ukrainian workers, Hahn and Horn were tasked with setting up the Arsenal factory exactly how it was in Dresden.

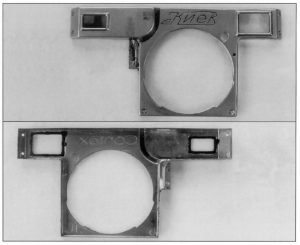

At this same time, back in Jena, a small team of Zeiss workers continued production on so called “Jena Contaxes”. These cameras were produced in very small numbers and sold to occupation forces to get enough money to buy food. From the outside, a Jena Contax and a Dresden Contax look identical. The only differences are in the shutter which had to be reverse engineered by technicians who never worked on the original design. Today, these Jena Contaxes are extremely rare and sought after. A large number of fakes have been made usually with Soviet built Contaxes emblazoned with Carl Zeiss Jena logos. For the collector looking for a real Jena Contax, the only way to tell the real from a fake is by internally examining the shutter.

Back in Kyiv, work continued on learning how to operate the relocated machinery and training local workers to make cameras. Assembly line workers practiced using spare parts originally made in Germany as a number of prototype cameras were produced. In October 1947, the Arsenal factory was confident enough to take on full scale production of the new camera, and the Jena plant was dismantled and shipped to Kyiv where it was integrated into the equipment already there.

After the closure of the Jena plant, production of a new Kiev II and III began in 1947 and 1948 with identical specifications as the original Contax II and III. A large number of parts, including lens mounts and body castings were left over Contax parts. If you take apart an early Kiev, and look behind where the Kiev logo is stamped, you can see an original Contax logo filled in.

At this point, the story of the “Kiev Contax” is beyond the scope of this article, so I’ll stop here. The Soviet Union would continue production of the Kiev rangefinder until 1987 with only minor changes the original formula built by Hubert Nerwin, making the lineage of the Contax II and III an astounding 51 years.

Today, cameras bearing the name Contax are extremely collectible. Everything from prewar rangefinders, screw mount SLRs, and even the Yashica/Kyocera Contaxes of the 80s and 90s are sought after for various reasons. Prewar Contaxes like this are special cameras, and like they did in the 1930s, are still compared to Leicas with some having strong preferences for one over the other. Although the values on these cameras are still quite high, they pale in comparison to the inflation converted prices of what these cost new. If you’re in the market for one, like any camera over a half century old, it is not immune to needing some level of cleaning or repair, but sadly, getting these fixed is a lot harder and more expensive to do than other cameras of the era, so buyer beware!

My Thoughts

Having shot several different Soviet made Kiev cameras which are based on an identical design to the prewar Contax II and III, I always assumed that shooting the real thing wouldn’t be much different, so when I had a chance to pick up a heavily worn, but still good condition Contax III for a reasonable price I jumped at it.

Comparing a Contax III with a serial number dating it to 1939 to a Soviet Kiev 4 with a serial number dating it to 1970 isn’t as straightforward as you might think. While both cameras come from the same exact design, a difference of 31 years is a lot. Plus, with there being so many Kiev 4’s for sale, I had my pick of hundreds when I bought my Kiev 4, so I went after one in known good condition. The Contax III however, was heavily worn, and barely worked. The front element of the Sonnar f/1.5 lens was extremely scratched up as if someone exclusively used gas station bathroom paper towels to clean it, the knobs were stiff, and the shutter fired at questionable speeds.

In use, the differences between the two are negligible, with most of the controls having only minor changes. The top plate largely looks the same. with a large diameter film rewind knob on the left that also doubles as the calibration for the top mounted meter. On the raised selenium meter we have the accessory shoe and meter readout. Whether you’re looking at the original Contax, or a Soviet made Kiev, understanding the meter requires you to read the manual (or this review).

Before you can take a meter reading, you must set the film speed using the knurled ring below the rewind knob. Film speeds are displayed in a small square window and use the DIN scale. In the image to the left, the number 12 is seen, which coincidentally the conversion from DIN to ASA is still 12. The highest number of DIN 24 is the same as ASA 200.

With the correct film speed set, you point the meter window with the door up, towards your subject and look at the analog needle on the top of the camera.

As the selenium exposure meter detects light, it will begin to move the needle. The idea is to get the needle to point to the black diamond near the bottom. To move the needle, you rotate the second knurled ring below the film speed ring until the black needle points to the diamond.

Now with the needle pointing to the diamond, look at the two rows of f/stop and shutter speed numbers in between the two knurled rings to determine the correct settings for a properly exposed image. In the previous image, assuming the needle was pointing to the diamond, any combination of f/2 @ 1/1250, f/2.8 @ 1/500, f/4 @ 1/250, f/5.6 @ 1/125 and so on, would result in a properly exposed image. If, for whatever reason, you can’t get the needle to move all the way to the diamond, and it is pointing to one of the numbers from 2 through 40, then you select an appropriate shutter speed or f/stop that is that many stops below what the meter suggests. The numbers 2 through 40 refer to exposure multipliers, which the manual explains are simple 1 stop conversions, so 2 = 1 stop, 5 = 2 stops, 10 = 3 stops, and so on.

If this exposure metering system sounds complicated, that’s because it is. To give Zeiss-Ikon credit, this was the first implementation of one on a 35mm camera, so they were kind of “winging it”, and later Contaxes ditched the multiplication scale.

The right side of the top plate has the exposure counter which counts backwards, showing the number of exposures remaining, like a Kodak Retina, instead of how many you’ve made. Next is the combined shutter speed selector and film advance knob, and in it’s center, a cable threaded shutter release. Changing shutter speeds requires lifting the ring around the shutter release and rotating it until a mark lines up with your desired speed and allowing it to drop back down into position.

A little known feature of the Contax because it is so often covered up with dirt, is that there is a little red dot near the center of the shutter release, that when you press down on the button and twist it, will rotate the shutter release into a locked position, giving you the ability for long exposures, similar to what a T mode would do. This can also be accomplished with a locking shutter release cable and B mode however, which is what I guess most people did.

Interestingly (I did not know this until I read the manual) is that back in the 1930s, you could get “Contax 35mm film” which came on metal spools wrapped in a very long paper leader to protect it from light. When loading Contax film into a Contax, a special loading process must be followed in which you attach the paper leader to the take up spool inside the camera, then close it, set the exposure counter to the number 27, lock the shutter release by pressing and twisting the shutter release, then rotating the film advance knob nine times until the number 36 appears on the exposure counter, then releasing the shutter lock, at which time you are ready for your first exposure.

An often repeated warning about Soviet Kiev cameras is that you should never change shutter speeds until after cocking the shutter, or risk damaging the camera. According to the Contax III manual, this precaution is not necessary as it specifically says that you can change speeds with the shutter cocked or not. The only warning being given is that you do not try to change speeds with the shutter partially engaged.

The bottom of the camera has both locks for securing the film door, and also for opening and closing either Contax or Leica reloadable cassettes. In both cases, each cassette type has a spring loaded clip that seals light out of the cassette when it is not in the camera. Rotating these locks releases the tension on these clips, allowing film to easily transport in and out of the cassettes. In the center is a folding foot for supporting the camera when placed on a flat surface and also a 3/8″ tripod socket. If you wanted to mount this camera onto a modern tripod, you’d need a 1/4″ converter.

With the back off, we see the Contax’s distinct film compartment. If you consider that in 1936 when the Contax II first made it’s debut, no Leica owner had ever seen their film compartment, and there were very few other 35mm cameras at the time, this was the first look for many owners, which is impressive considering how similar it is to modern cameras.

The two most notable differences are in the horizontal “garage door” slats that make up the metal focal plane shutter, and that the take up spool is removable. Ideally, if you acquire a Contax, you want to make sure it has a take up spool inside of it, but if it doesn’t, the inner spool of a normal 35mm cassette will work too.

Film transport is from left to right and other than having to deal with the spool, loading film is pretty uneventful. The inside of the film door has a polished metal pressure plate and a film flatness roller to aide in film transport, and in the image to the right, you can see the other side of the door locks that also unlock Contax and Leica cassettes.

Up front is where the camera is most familiar to anyone whose used a Kiev or even a Nikon rangefinder as both cameras use a very similar (but not identical) lens mount. The differences between Nikon’s mount and the Contax/Kiev are not external and don’t change how to mount and dismount lenses.

The Contax mount has both an inner bayonet which is only compatible with 50mm lenses, and an outer bayonet for everything else. For the 50mm Sonnar seen here, a metal clip on the lens mount near the 12 o’clock position holds it in place. Simply press down on the clip towards the back of the camera and rotate the lens until it releases. Mounting it is the opposite.

For non 50mm lenses, each lens has twin spring loaded clamps at the 3 o’clock position around the lens which must be squeezed while rotating the lens but otherwise mounting and dismounting those is the same as the 50mms.

A feature retained on the Contax III and all subsequent Contaxes, Kievs, and Nippon Kogaku’s loosely based copy of the Contax, is the top mounted precision focus wheel. Conceived by Dr. Heinz Küppenbender when he created the very first Contax, it was thought that photographers would prefer to focus the lens using this wheel, located just in front of the shutter wheel.

If you didn’t want to use the wheel, Contax lenses could still be focused by rotating the barrel which is what a majority of people did. But even if you didn’t want to use this auxiliary focus wheel, the button behind it was necessary to override the lens’s infinity focus lock. Contax lenses are designed to lock at infinity, requiring a downward press of this button to be able to unlock it. While using the wheel, this is very easy to do as you just press down on it while rotating the wheel with the same finger, but if you want to focus the lens using the lens itself, you still need to press down on this button to unlock it.

For delayed action exposures, the Contax III has a mechanical self timer to the left of the lens mount. To activate it, rotate it counterclockwise as far as it will go, and when you’re ready to begin the countdown, slide a small button found behind the lever in the direction of the arrow.

The viewfinder of the Contax III is very small, which when the original Contax was released in 1932 was pretty normal for a rangefinder camera, but was something that wasn’t significantly changed with post-war Contaxes, or any Kiev cameras throughout that model’s entire production.

Combined with the very small opening and lack of any sort of adjustable diopter means seeing the entire 50mm frame at once while wearing glasses is impossible and without a doubt my least favorite thing about using the Contax. This is one area that Nippon Kogaku greatly improved with their Nikon rangefinders, and even the Kiev Arsenal did see a larger viewfinder on the short lived Kiev-5, but not something you’ll see on any German built Contxaes.

The viewfinder on this particular Contax III was very cloudy and difficult to see through, so for the previous image above, I’m showing what my 1970 Kiev 4 looks like. Since the two cameras use identical designs, you likely wouldn’t have known the difference had I not told you. With the Contax’s extremely wide rangefinder base, there is a huge amount of separation between the central rangefinder patch and the rest of the image. This makes precise focus on the Contax very easy, especially with telephoto lenses where getting sharp focus on early rangefinders can sometimes be very difficult.

Having used a Kiev rangefinder prior to this Contax III, I pretty much knew what to expect, and for the most part the shooting experience is similar. German built Contaxes were gloriously over-engineered precision devices every bit worthy of their reputation as some of the best in the world. Quality control on the Soviet versions are all over the place, but if you can get one in good condition that’s been regularly serviced, the experience is close enough that most people won’t care. Of course, if you want the real thing, you need the real thing, which leads me to the next section…

My Results

Before having shot the Contax III, I had some reservations of it’s operational condition. The shutter did fire, but upon looking at the rear curtains, you could tell there was some play in it. Comparing the curtain to that of my Soviet Kiev 4, the Contax’s curtains were wavy, as if they were loose or something. Furthermore, the f/1.5 Sonnar had an extremely scratched front element. The rear elements look OK, and I didn’t see any noticeable haze or fungus, so I thought that it might shoot OK, but just in case, I decided I would shoot this first roll half using the Zeiss Sonnar, and half using the Jupiter 8 from the Kiev that I knew was optically excellent. I loaded in some fresh Fuji 200 and went shooting.

If it seems like I probably should have included more than 11 images from a historically significant camera like the Contax III, you’re right, but sadly my pre-shooting concerns about the Contax’s shutter proved to be valid as after these 11 images, one of the curtain ribbons snapped. The issue with the curtain looking wavy was likely that one of the ribbons had already started to come undone and wasn’t keeping it tight, and after the stress of these first 11 shots, it gave way.

In what ultimately becomes a huge deciding factor with collectors today who also like to use their cameras, when looking at both a Contax and a Leica, both cameras suffer the rigors of time equally, as 81 years is a lot of time to expect anything to work without service, but today, getting a Contax serviced is significantly more difficult than a Leica. Where there are still dozens of people in the US and many more overseas who can completely overhaul a Leica with new curtains and some replacement parts, there are but a small handful of people willing to take on a Contax, and when they do, they often rely on parts swapped from other cameras. One such Contax repair expert, Henry Scherer is not only expensive, but reportedly has a multi-YEAR backlog of repairs.

Even though I was unable to get through an entire roll of film in the Contax, I am grateful that I was able to shoot it at all, and in the short time I was using it, I feel as though I can draw some conclusions.

I am not going to even bother touching the Leica vs Contax argument as these cameras are so different, it’s not fair to compare them. It’s like comparing a helicopter to an airplane. Both can get you from point A to point B through the air, but how they accomplish that task is different.

A more worthwhile comparison is to the Soviet era Kiev rangefinder, after all, unlike Soviet FED and Zorki rangefinders who were cheaply reproduced copies of the Leica using parts and tooling entirely created in the Soviet Union, early Kievs ARE Contax cameras. A large number of early Kievs used spare Zeiss Contax parts, and all were built on the same machinery using the same tools and equipment as the prewar German cameras. As time went by and the original spares ran out, later Kievs were still built using these same machines. Sure, quality control dropped, but otherwise the cameras are basically the same.

Does that mean shooting my 1970 Kiev is exactly the same as a pre-war Contax? No, as there are still some pretty obvious differences in quality. For starters, the chrome finish of the two cameras is clearly different, with the German Contax’s being shinier and “more chrome-like” whereas the Kiev has a duller, more textured matte surface that also feels thinner. Looking at light glistening off the Contax’s finish was sorta like looking into a high quality paint job done on a custom hot rod, versus a simple Maaco paint job.

Despite the three plus decade difference in age and being a bit stiffer, the Contax’s knobs and dials all turned smoothly, with no slop or grit. My 1970 Kiev being in excellent condition turns smoothly too, but I’ve handled many other Kiev cameras that aren’t as nice. Of course, it’s not fair to draw conclusions of two cameras based on one sample, but I feel as though that more times than not, the controls of the Contax would have maintained their German level of precision, whereas the Soviet versions are likely all over the place.

Film transport on the Contax was also remarkably smooth. I’ve used several Kiev rangefinder cameras and all seemed to have more resistance in them. Whether this is due to changes intentionally done to make the cameras easier to produce, or if the Germans were just better at this is anyone’s guess.

If you’re a collector looking to buy a pre-war Contax for it’s history and to display it on a shelf, then by all means do it. These are special cameras worth owning. If however you want to shoot it, you might be better off with a Kiev 4. The two cameras are not identical in build quality, but the shooting experience is nearly the same, and you’re going to have a MUCH easier time finding a working Kiev as there are quite a few sellers in former Soviet Union countries who still work on them. If a shutter on a Kiev dies, you can swap it out with a shutter from one of the other million out there. It certainly won’t be new, but it will work and for the price of a nice, confirmed working prewar Contax, you could buy 4 Kievs and get one that makes images that for anyone who didn’t know any better, look indistinguishable from those shot on a Contax.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Contax_rangefinder

https://kosmofoto.com/2018/06/contax-iii-review-nigel-haycock/

“Starting with the shutter, which on the Leica traveled vertically across the 36mm film plane, was made of cloth,”

This sounds “interesting,” since in the “double frame” 24X36mm format adopted by Leitz, 24mm is the Vertical dimension, while 36mm is the Horizontal dimension. The rest of the paragraph makes it clear that this is how things are when the Leica is used to take horizontal /Landscape pictures.If one takes Portraits, then the Leica shutter curtain does travel vertically.

Otherwise, the article about the Zeiss Contax camera system is fascinating for this former Nikon S2 user.;)

Doh! I have fired my proofreader! Thanks for catching that! 🙂

Mike, I hope you haven’t yet fired the proofreader. The fact is, in a normal 35mm camera, the vertical travelling focal plane shutter travels the shorter, 24mm, frame distance, and in the Contax III travels downwards from the top of the camera to the bottom. A horizontal shutter always travels the longer, 36mm, distance and travels left to right in most cameras. Swinging either camera through 90 degrees doesn’t change the mechanics of the shutter one iota. Vertical and horizontal always refer to the motion of a shutter relative to the body, not camera orientation. Otherwise, if a camera is held on a 45 degree slant, what would this make the shutter?

Thanks for another interesting review of a classic camera and having an excellent example of the III myself I can appreciate your thoughts on it. Clearly, there is a close parallel with the Kiev, and indeed the first Kiev’s could rightly be called a Contax, considering they were made from the Zeiss spare parts bin appropriated by the Russians. If you see a very old Kiev with a DIN speed indicator, this is the first clue, as later Kievs had Gost. My III has an M serial which puts it at 1940/41, and the DIN scale goes to 33, which I find strange for the period given how slow films were back then.

You referred to the double bayonet and this does have one advantage today over compatibility of lenses with a camera’s rangefinder in that both the Zeiss and Russian 50’s have perfect register, unlike trying to use unmodified Russian LTM lenses with a Leica body. I understand that Zeiss lenses will fit the Kiev, but not the other way round, well at least my Russian Jupiter-12 won’t mate with the Contax.

I should mention an advantage of cassette to cassette operation. Reloading the camera can be faster as it doesn’t require a film to be rewound, although in practise, I’m not sure how much quicker, and if it’s worth the fuss. But a real advantage has nothing to do with speed. It comes with the means by which they operate. Compared to normal daylight cassettes, they don’t use dust attracting felt light traps, but use a felt-less film gate. When inserted in the camera, the back locking screw opens the cassettes when the back is locked, and closes them when they are turned to release the back. So when a film is run through the camera it doesn’t run the gauntlet twice of being scratched by the velvet light trap. In fact, it means the film doesn’t run through a light trap at all, as a bulk film loader is used. Conventional cassettes can be reloaded but the film has to pass the velvet light trap, so the film ends up with three passes.

Incidentally, regarding “Contax 35mm Film” 35mm film was often sold as Leica film, and Daylight Loading Film was available which was 35mm film on a spool with the paper leader you mentioned.

My Contax iis (I’ve got two) work with pre and post war Zeiss lenses as well as with jupiters, including a Jupiter 3, 8, 9, 12 and a Helios 103. The iia and iiia don’t work with the Jupiter 12 or the post war Zeiss Jena Biogons. I’ve run at least 50 rolls through them and got the shutter of one repaired by Oleg Khalyavin. They are my favourite 35mm cameras and the lenses are gorgeous. I’d love to do cassette to cassette transport, though, as rewinding the film is a bit annoying.

Whenever I’ve felt the urge to shoot with one of my Contaxes I grab a Kiev! I always felt that Contax was a step ahead in fast aperture lenses (vs. Leica). Even today I occasionally use the 180mm Sonnar to good effect

I had a Contax III and it took great pictures but I just couldn’t get on with it and worries about the cost of getting it serviced pushed me to sell it on.

Wonderfully detailed and excellent review as always Mike

The Leica and Contax film cassettes are not compatible. Nikon and Contax are similar. The Ica factory where Contax were built in Dresden was totally destroyed in the February 1945 fire bomb raids. Otherwise, nice review.

Oleg Khalyavin repaired my postwar Contax IIa; it came to maybe a little over $200 including shipping both ways (and no multi-year wait!). I put a Helios on it and the performance is stunning. Maybe someday I will splurge on a Zeiss lens.

I have a Contax ii which broke after 5 frames, several Contax iia’s and numerous Kiev. One iia works well after service, but looks ugly. It had to be serviced twice. One Kiev 4 which is engraved as a gift to a KGB agent and appears little used is a magnificent camera, one of the smoothest I have used.

Maybe just nitpicking, but wasn’t the Contaflex TLR of 1935 the world’s first electrically metered 35mm camera? In any case, thank you for all the superb in-depth content and resources on your site – it has been very valuable for me when researching the history of 35mm cameras.

No guarantee he will say yes, but you might contact Stanislav at Mechanical Camera Repair to see if he can rebuild your Contax shutter. As an ex-Arsenal man, he’s at least seen a few of the Soviet version. Stan is America’s go-to guy for Pentacon Six / Kiev-6 cameras, BTW. http://mechanicalcamerarepair.com/?utm_source=gmb&utm_medium=referral

Nice review, but I noticed an error. You write that “For non 50mm lenses, each lens has twin spring loaded clamps at the 3 and 9 o’clock positions around the lens which must be squeezed together while rotating the lens but otherwise mounting and dismounting those is the same as the 50mms.” This is incorrect, as Contax RF (& Nikon RF) external mount lenses only have a single spring loaded clamp, which starts at about the 6:30 position (looking at the front of the camera) when 1st attaching the lens & then ends up at 3:30 when the lens is fully mounted. There is a little knob on the camera body at the 10 o’clock position, but that disengages the infinity lock & is automatically pushed over when you mount an external mount lens (if you move the knob manually you can see the infinity lock release button near the focus wheel move down).

You are correct. I don’t know what I was thinking when I typed that as I have several wide angle and telephoto lenses in Contax mount. I have made the correction! 🙂

Cool, I suspected that you wrote the article before you had a chance to own/use any external mount lenses on a Contax or Nikon RF! Reminds me that I need to “exercise” my Contax bodies (been on an Ektra binge lately for obvious reasons).

Chris, your description of how the external bayonet mount works is not correct.

What you refer to as a spring loaded clamp is not a clamp at all: it’s the lens lock. It’s not a clamp as it isn’t designed to apply any pressure to physically hold the lens, only to prevent the lens mount rotating as the lens helicoids are turned for focusing. This is important for proper alignment of the rangefinder coupling which relies on spring loaded couplers from the lens to the body focusing mount. If the lens isn’t locked in its correct position, the rangefinder will be inaccurate. This can be readily demonstrated by unlocking and turning the lens mount and noting that the rangefinder spot moves. Interestingly, the rangefinder coupler connects to the inner body bayonet lugs.

External lenses use three pressure arms, roughly 120 degrees apart, to grip the lens around the bayonet lugs of the external body bayonet. These pressure arms can be seen when looking into the lens mount circumference. It can also be seen that the spring locking lever plays no role in physically gripping the lens.

Thanks Terry for the correct terminology & description of the mount mechanism, but I was simply working off Mike’s use of “clamp” & correcting his original description of 2 of them. Although I am a longtime user of the Contax & Nikon RF systems (a Contax was my 1st all-manual, interchangeable lens camera), I’m obviously not an engineer or mechanic, so wasn’t sure how to describe these bits.

I would quibble with your statement that it “isn’t designed to apply any pressure to physically hold the lens.” You’re absolutely right that it isn’t a clamp to physically holds the lens onto the camera, but the lens lock, properly working, does have to apply sufficient pressure on the metal “latch” (again not sure what it’s called) that locks on edge of the 4 o’clock external bayonet lug to ensure that the base of the lens barrel doesn’t rotate clockwise & unmount the lens.

That latch/lug interface can occasionally be weak, however. For example, on my 35/4.5 Orthometar (c.1937), the “latch” only partially meets the edge of lug (probably because of wear or damage to the latch as the spring is pretty strong) so a small bump & a hard turn can start rotating the lens base. Fortunately, the Zeiss Ikon design requires the lens to rotate about 30 degrees before it completely comes off the external lugs, so there’s a safety margin. I also don’t use the Orthometar that often, but when I do, I’m careful to ensure that the latch is fully engaged!

Chris, I, too, had to resort to my own description of the parts! It was easy refer to the lens lock mechanism, as this is its function, latch seems as good as anything, but I haven’t a clue what is the correct terminology for the three gripping parts of the lens mount, they only apply pressure, and as springs didn’t seem appropriate, I came up with pressure levers.

But my use of “clamp” follows the accepted norm for something that grips or applies pressure to hold parts together, and it is in this context that I don’t accept that the lens lock mechanism is a clamp as such in that it only prevents the lens from rotating, and there is no actual pressure applied to the lens to do this.

I’ve no experience of using the Nikons, but I do have all Contax bodies from the 1, v.7, to the IIIa, and wonderful they are too.

This write up has strengthen my enjoyment of owning both my Contax IIa and IIIa since the time I bought cameras, in Summer of 1993 as 22 year old, who wanted the best camera that I could afford at the time. Thirty years later, these cameras are still in my possession as everyday shooters, to me that’s the testament to the men and women at Zeiss Ikon who engineered, built and serviced these beautiful cameras.

Oleg is a good option and much cheaper than Henry. Sent my contax ii and 4 lenses to him last year for a cla and was around $400. May get another as a backup and will send it to him also.

Do you have contact information for Oleg? I just acquired a Contax III and would like to have a cla done on it. Thanks, Al

Like Silver Fox, I too had a Contax, a 111a (date unknown but it was a coloured dial). I used it alongside my pair of Leica M3 for a number of years. When I bought a Leicaflex SL a few years ago, I got my partner to pop it on eBay and I got a good price for it. I didn’t use the rangefinder as it was too ‘squinty’. I popped the 5cm Leitz bright line finder in the accessory show and estimated distance using the focus scale I was always conscious of the difficulty of getting repair. That was the main reason I sold it.

However, I discovered the Leica R8 a few years ago, again repair appears to be non-existence. So, belt and braces, I bought three bodies. Fortunately, the lenses I had acquired for the Leicaflex were all three cam, bar the Schneider PA Curtagon ‘shift’ lens. That resides on the ‘flex.

I’m currently tempted with a Contax 111, circa 1936.

Hi Mike,

I’m French.

Your Zeiss website is excellent. I have a Contax III in good condition.

Note that mine is different: the diameter of the female screw on the base plate is smaller than on others versions.

And the male screw on its original leather case fits.

Are these early Contax IIIs (before 1936)?

Looking forward to hearing from you.

Sorry for my English.

Best regards,

Patrick

Patrick, thank you for the nice comment. If your Contax has the smaller 1/4″ threaded hole on the bottom, most likely there is an adapter screwed in. Many early European cameras with the larger hole were given adapters to shrink the hole down to be used with modern tripods. They’re very small, so easy to miss. As for whether or not a Contax III could be from before 1936, the answer is no. The original Contax was produced until that year, and the Contax II and III did not come out until that year or later. You can easily date your camera by looking at the letter at the beginning of the serial number. Simply Google “Zeiss Contax Serial Numbers” and you’ll find a variety of sites explaining the date codes.