This is a Yashica 44 Twin Lens Reflex camera made by the Yashica Company, Ltd, in 1958. The Yashica 44 is designed for 127 film unlike most other TLRs of the time which used either 120 or 620 film. Using 127 film, this camera made images that were 4cm x 4cm, hence the ’44’ name. Other than the film type, and being about 3/4ths the total size, the Yashica 44 is nearly identical in every way to the larger Yashica-Mat TLRs. The Yashica 44 was a mild success, spawning 3 different variants and remained in production until around 1965.

Film Type: 127 (Twelve 4cm x 4cm images per roll)

Lens: 60mm f/3.5 Yashikor coated 3-elements (Taking), 60mm f/3.5 Yashikor coated (View)

Focus: 3.3′ to Infinity

Type: Coupled Waist Level Reflex Viewfinder

Shutter: Copal SV Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Weight: 712 grams

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/yashica_pdf/yashica_44.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Yashica 44 was an excellent Japanese copy of an already excellent German camera. It was built with very high quality standards with an excellent lens, a bright and easy to use viewfinder, and easy to use controls. It’s small size and light weight make it more portable and easier to carry than a full size TLR, and despite the lack of availability of modern 127 film, is very easily adaptable to 35mm film which produces unique looking images with exposed sprocket holes. Shooting 35mm film in the Yashica 44 might not be for everyone, but the results from my first test roll were very impressive and offer a unique look that no other camera in my collection can duplicate. I cannot wait to shoot this camera again and recommend anyone reading this article try one out for themselves. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 30% | |

| Bonus | +1 for the extra cool factor of shooting 35mm film in a camera not designed for it | ||||||

| Final Score | 11.4 | ||||||

History

In the early days of film photography, many different variations of film sizes and formats were invented. Some succeeded, but many didn’t. Wikipedia has a nice chart of almost all of the early formats of roll film and a little bit of info on each.

In 1912, Kodak designed a compact new format of rollfilm using a 46mm wide film stock, which was called 127 film. This film was designed to be used in a new line of compact “Vest Pocket” folding cameras. These early VP cameras became popular during the first world war because of their compact size. Many were used to shoot some of the first war footage by soldiers, and the VP camera quickly earned the nickname as the “Soldier’s Camera”.

During the next 2 decades, 127 format film was the preferred choice for those looking for a compact portable camera. 127 film had an exposed image width of 40mm, and a length which was variable from 30mm to 60mm depending on camera. Although smaller than other roll film cameras, it was still larger than newer compact cameras like the Leitz Leica which was designed for perforated 35mm cinema film.

In March 1931, the German camera maker, Franke & Heidecke introduced a new semi-professional Twin Lens Reflex camera designed for 127 film, known as the Rolleiflex 4×4. It quickly earned the nickname as the “Baby Rollei” as it was a nearly 3/4th scale model of their popular Rolleiflex camera which used 120 format roll film. The Baby Rollei’s smaller size meant it was more portable, and easier for children and other people with small hands to use.

The camera was fairly successful, with an estimated 400,000 made between 1931 and 1941. According to the Chronology page at rolleiclub.com, around 1,000 Baby Rolleis were made during World War II, but these are unconfirmed by Franke & Heidecke, and are extremely rare. For some reason though, after the war, the Rolleiflex 4×4 model was discontinued, and the company’s entire production of TLRs was of the full size 120 version.

Fast forward another decade and a half, there was an increased interest in a compact TLR, so in 1957, Franke & Heidecke would re-design an all new Rolleiflex 4×4 model, and base it off their current line of full sized TLRs. Once again, this new model would be nicknamed the “Baby Rollei” and would shoot 40mm x 40mm images on 127 film. It is quite easy to tell the difference between the original Baby Rollei from the 30s, and the 1950s version as they look very different.

Unlike its first production run in the 1930s, by the late 50s, there was a huge industry in Japan where several companies would release their own versions of German designed cameras. Almost immediately after the release of the new Baby Rollei, several Japanese companies would respond with their own 127 format TLR that bore a strong resemblance to the Baby Rollei. Minolta, Topcon, Ricoh, and Walz all released their own models, known as the Miniflex, Primo Jr (sold as the Sawyer’s Mark IV in the US), Ricohmatic 44, and Automat 44 respectively. Of all of these companies, perhaps the most successful was Yashica.

Yashica’s 127 format TLR was given the simple name of Yashica 44, and shared many similarities with the Baby Rollei to which it was inspired by. Both the Yashica 44 and Baby Rollei shared the same Bay 1 mount and gray paint and body covering. It was this gray color that seemed to bother Franke & Heidecke the most as they would take Yashica to court, and in a ruling, Yashica was required to offer the Yashica 44 in colors other than gray. As a result, there exist Yashica 44s in 8 different color combinations, ranging from all black, to other colors like Lavender, Burgundy, Golden Brown, and Pastel Blue.

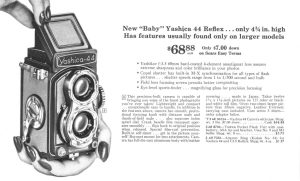

The Yashica 44 was produced from 1958 to about 1965 at which time, interest in the entire 127 film format was rapidly declining. During this production run, 3 different major variations to the Yashica 44 were made. There was the original model with a crank film advance, the more basic Yashica 44A which lacked the Bay 1 filter mounts and featured a more basic knob wind, and then finally, the Yashica 44LM which had the Bay 1 filter mount, a knob film advance, and a selenium cell light meter. According to page 18 of the the 1959 Sears Photo Catalog, a Yashica 44 sold for $68.88, which when adjusted for inflation, is like $572 today.

Normally, I would continue to type up a few more paragraphs about the Yashica 44 sharing some information I found online in the hope of piecing together an accurate chronology of the model’s history, but in this case, there already exists an excellent website which has done this for you. If you are interested in a really fascinating and in depth look into the Yashica 44, its history, and all of it’s variants, I encourage you to take some time to visit Paul Sokk’s Yashica TLR website. Quite simply, Mr. Sokk’s website is the most informative and most well put together website for any type of camera. The level of detail and thoroughness of his research is amazing. He covers all Yashica TLRs, not just the 44s, and even if this is a model of camera you have little interest in, I strongly encourage you to take some time to browse through his site.

So with that out of the way, I don’t have much else to say about the Yashica 44 other than it was a well built, compact camera, that used 127 format film at a time when there was still demand for small roll film based twin lens reflex cameras. By the time the mid 1960s had rolled around, the need for a camera with the design and features of the Yashica 44 had disappeared, and as a result, the entire line was discontinued.

127 format film would still be made by Kodak until 1995 at which time they discontinued the format. Most of Kodak’s competitors would soon follow, leaving only the Croatian company, Fotokemika to continue making their Efke 127 film which they still make to this very day. Unlike other extinct formats of roll film, 127 is still available fresh from boutique distributors such as Bluefire in Canada and Kawauso-Shoten (Rerapan) in Japan. In addition, some hobbyists will take 120 format roll film and cut it down to 127 size and spool it onto empty 127 spools allowing for unique combinations of film never designed for 127 like Kodak Ektar or Ilford HP5 to be used in 127 film cameras.

Today, the Yashica 44, like all 127 format TLRs are highly collectible. They appeal to a large group of people who like the look of TLR cameras, but also those who enjoy their petite size, and various color combinations. The original Yashica 44 being reviewed here is unique in that it’s the only model with a crank advance, and an automat design which stops on each frame without having to rely on a red window.

Loading 35mm Film

There are a fair number of Twin Lens Reflex cameras that are designed for both 120 and 35mm film using a removable adapter such as the Yashica 635 and Flexaret VII, and even a few designed specifically for 35mm natively, like the original Zeiss Contaflex from the 30s but to my knowledge, no 127 TLRs were ever designed to load in a 35mm cartridge. This is surprising considering the similar film stock width of the two films. 127 film produces images that are 40mm wide, and the width of 135 format film is 35mm. Of course, that 35mm width of 35mm film includes the space needed for both sets of sprocket holes. But still, even when considering the normal width of the exposed image of 24mm, the exposed width of 135 format film can use 60% of the usable image space of 127 film. If you can accept seeing sprocket holes in your exposed images, 35mm film takes advantage of 87.5% of the width of 127 film.

Compare this to the width of 120 film which has an exposed image width of 60mm, when you shoot 35mm film with an adapter in a camera like the Yashica 635, you will only use 40% of the exposed image area. This can make composition difficult since you will only be able to use roughly 40% of the viewfinder of the TLR camera.

So, while I don’t know of any 127 format TLRs that originally were designed to use 35mm film, the Yashica 44 (and all it’s variants) are easily adaptable. In fact, the whole conversion requires only 2 steps, and both are completely reversible back to stock in case you wanted to go back to using 127 film, or restore the camera to it’s original design.

When looking at the supply side of the film compartment, you’ll notice there is a roller on the leading edge of the compartment that gets in the way of the 35mm canister. This roller serves no purpose for 35mm film, so it just needs to come out. Remove the two screws on each side (indicated with yellow arrows in the image to the left) and put it aside. I recommend reinstalling the two screws back into their holes for safe keeping since they’re a lot easier to lose than the roller itself, in case you ever want to restore the camera back to it’s original condition.

Step 2:

127 film, like all roll film, has a paper backing with numbers on it used for frame spacing. 35mm doesn’t have this paper backing, so there is risk of light leaking in through the red window on the back door of the camera. As a result, you need to do something to block off this window to assure that no light leaks in through this door. Even though the Yashica 44 does have a sliding metal door to keep light out, it is not light tight and should not be trusted by itself. You can be as creative as you want and slide some type of black foam or felt beneath the film pressure plate to cover the hole, or you can just do what I did and place a piece of black electrical tape over the outside of the door to keep light out.

Step 3: (Ok, I lied, there’s 3 steps)

Step 3: (Ok, I lied, there’s 3 steps)

Since you’ll need to thread the 35mm film leader into a 127 spool, you’ll most likely have to cut a small notch through the sprocket side of the film leader so that it can be tightly wound around the 127 spool. Since 35mm film is not as wide as 127 film, you’ll need to make sure that you center the film onto the 127 spool as best as you can. You want it to wind onto the spool as straight as possible while it is in the camera.

Step 3b: (I feel bad continuing to be wrong about the number of steps, so I’ll just call this step 3b)

Step 3b: (I feel bad continuing to be wrong about the number of steps, so I’ll just call this step 3b)

The last thing you’ll need to do is devise some type of spacer for the 35mm cassette since it is also not as wide as an original 127 spool. Looking down on the film compartment with the 35mm cassette on top, the left side of the cassette should sit flush with the roller because of the plastic protrusion that is on every 35mm cassette, but you’ll need to fill the space on the right side. Thankfully 3 US pennies work perfectly. Another walkthrough of this conversion by Mick Feuerbacher says that 3 Euro pennies work as well for those of you in Europe.

Once you have the film loaded into the camera, you can close it up and get it ready for shooting. Like with any 35mm film, you need to advance the film enough to get the exposed leader out of the way. In a normal 35mm camera, two full frames will get you there, but on the Yashica 44, it takes approximately 2 advances of the wind lever to equal one full frame so to get the film ready for the first exposure.

Your Yashica 44 is now ready to shoot. There are a three things you need to keep in mind when shooting 35mm film in a camera designed for 127. The first, is that you no longer have a functioning frame counter. You will need to keep advancing the film blindly until you “feel” the end of the roll. For reasons I’ll explain later, you must advance the film crank two full turns in between each shot to clear enough space on the film for the next exposure.

The second thing to keep in mind, is that 35mm film is slightly narrower than 127 film, which means that the edges of what you see in the viewfinder will be cut off. Since you will also be exposing the sprockets on the film, you need to make sure that anything that is really important in the image is centered in the image. You could get really creative and create some kind of “mask” to lay on top of the ground glass inside of the viewfinder, or just make a mental note to ignore the sides.

Finally, after reaching the end of the roll, there won’t be any way to rewind the film back into the canister. You’ll need to do this in a dark room or film changing bag, so make sure you resist the temptation to open the camera at the end of the roll, like you would with any other roll film camera.

My Thoughts

I have a bit of a love / hate relationship with TLRs. On one hand, the Twin Lens Reflex style of camera is one of the most distinct and often beautiful designs of cameras made over the past 100 years. Many models like those made by Yashica, Franke & Heidecke, Minolta, and many others were very well built cameras with state of the art optics, and are capable of excellent photographs. Whether you like to display them or shoot with them, you really can’t go wrong with a TLR.

On the other hand, TLRs by their very design are not the most portable cameras to use. While the waist level viewfinder on higher end TLRs are bright and easy to use, many early models like the Ciro Flex or the Argoflex are extremely dim and hard to use in anything but the most optimal lighting conditions. Also, because the viewfinder is flipped horizontally, it takes additional time to capture spontaneous shots like that of a child or fast moving object. Finally, their weight and size make them harder to casually stick into a coat pocket for “walk around” access, and having one hang from your neck or wrist for any extended length of time would be a chore.

So, while I am pleased with the TLRs that make up my collection, they’re not exactly the first “go-to” cameras I reach for when casually going out to shoot some pictures. I had always known that the 127 TLRs were smaller, but it wasn’t until I handled this Yashica 44 for the first time, did I realize exactly how tiny they are. On paper, a Yashica 44 is three fourths the size of a full size Yashica TLR, but that’s misleading. The camera is smaller in every dimension, height, width, depth, and weight. According to my wife’s kitchen scale, without film loaded, the Yashica 44 weighs only 712 grams which is lighter than pretty much every SLR and many rangefinders in my collection.

While it’s still not quite as pocketable as a point and shoot, it is much easier to hold one handed or stick into a small camera bag. You could very easily have a small SLR bag hanging from your neck or shoulder and easily slip this thing in and out with ease while walking around the zoo or a park.

Loading film into the Yashica 44 is like other roll film TLRs with one exception which is that the takeup spool is on the bottom of the camera, and the supply side is on top. Most TLRs have it the other way around where the supply side is on the bottom. In some ways, having it like the Yashica 44 makes a little more sense since the film has a straight path from spool to the film plane. It does not have to make a 90 degree turn until after the image has been exposed whereas if the supply side was on the bottom, the unexposed film would have to go around this turn before being exposed. In either case, I doubt it makes any real world difference. In the image to the left, the camera has a fully exposed roll of film on the take up spool. This roll of film came with the camera when I acquired it, and I plan on sending it in to get developed. Edit: There was nothing on the roll.

The Yashica 44 is not a full “automat” camera in the sense that you still need to rely on the red window on the rear door to get the film ready for the first exposure. Upon closing the door with a new roll of film loaded, you must open the slider on the rear door and advance the film until the number ‘1’ appears behind the door. Once the film is at the first exposure, you can close the metal door and you wont need it again for the rest of the roll.

All of the controls, including the shutter release, are exactly where you’d expect to find them on pretty much every other TLR. The original Yashica 44 being reviewed here has a wind crank for film advance as opposed to other models which reverted back to a knob. Upon advancing the film crank, the camera automatically advances the film to the next exposure and stops. There is a small exposure counter just above the crank which shows how many exposures have been shot on film. This counter obviously assumes you are using 127 film, so its not really useful when shooting 35mm in the camera.

Thankfully, Yashica maintained it’s excellent reputation of bright and easy to use viewfinders as the viewfinder is very clear and easy to use in all but the lowest of light conditions. Like other TLRs, there are red marks to help orient your image on the horizontal and vertical axis, and there is even the little flip out magnifying glass for fine focus work.

The front of the camera has controls for aperture and shutter speed around the taking lens. Unlike the Yashica-Mat and Yashica-D in my collection, the settings are not visible from the top of the camera. You must look at the side of the shutter to see the settings. It’s not difficult by any means, but slightly less convenient than Yashica’s full sized models. The Yashica-44 also has a standard bayonet mount for filters, hoods, and other accessories. Strangely, I had access to a Rollei 4×4 hood from a Baby Rollei that looked like it would fit the Yashica-44, but it would not fit. I am unsure whether there is something defective with my camera, the hood, or if Rollei hoods simply were not compatible with the Yashica camera.

Once you have film loaded in your camera, its ready to shoot. Using the camera with 35mm instead of 127 is mostly the same, with the only exception that you need to remember that the very edges of the viewfinder will be cut off or covered in sprocket holes. The “usable” portion of the 35mm film covers roughly the middle 60% of the viewfinder. You could make a mask to block off the edges of the viewfinder, or just mentally try to keep your subjects in the center and you should be fine.

When advancing the film, you must start out advancing two full cranks of the film advance after each shot. Because a 24 exposure roll of 35mm film is longer than a normal roll of 127 film, you will get more than the standard 12 exposures on a roll of 127, however the frame spacing will increase towards the end of the roll. I imagine you could use a 36 exposure roll, but the spacing will be even greater near the end. On my inaugural roll, I got 16 exposures from a 24 exposure roll of film. I might have been able to squeeze an extra frame or two by modifying how much I advanced the film near the end of the roll, but that gets confusing so I just recommend always advancing two cranks of the wind lever for all 16 shots.

If this seems confusing, look at the image above of my roll of 35mm film where I advanced twice after every frame. Notice that after each frame, the spacing gets larger and larger. Around the 11th frame, I am wasting the equivalent of an entire extra frame in between each exposure.

My Results

Although I was using film in a camera not designed for it, I was pretty optimistic that I would have some pretty good shots. For one, I was lucky to find a Yashica 44 in excellent condition that exhibited no signs of a sticky shutter. All of the controls including focus, aperture selection, and shutter speed seemed to work as intended, and the glass appeared clean. Yashica generally made excellent lenses and while I had never used a camera with a Lumaxar lens before, if it was anything close to the Yashinon lenses used on other cameras, I was in for a treat.

I took the Yashica 44 with a roll of fresh Fuji 200 to a Labor Day parade and shot the entire roll. I got 16 exposures on that roll, and made an attempt to shoot at least a couple in landscape orientation just to see what that would look like.

I sent this roll to Dwayne’s Photo in Parsons, KS and included a note that I wanted the film scanned with the sprockets in tact. They informed me that this would be a $5 surcharge for scanning which I agreed to, but it brings developing and scanning to $14 per roll. For me to want to use this camera on a recurring basis, I’ll likely want to develop and scan, or at least scan the film myself to save some money.

The most obvious issue are the red splotches on most frames. Clearly, I did a poor job of blocking light from entering the rear red window. I had applied a piece of electrical tape over the exterior part of the window, but obviously that wasn’t enough. In Mick Feuerbacher’s original conversion article, he mentions inserting something inside of the rear door to block light, which I didn’t do thinking a piece of tape would be enough. Well, sadly, it wasn’t. For my next roll, I will definitely do a better job of keeping light from entering this window.

Besides the light leaks, the images came out excellent. I shot everything using Sunny 16 and found the exposure to be perfect. This suggests that the shutter speed is accurate at 1/125 and my choices for aperture were spot on. I especially like the lighting on the Indian motorcycle image.

The horizontal images came out nice giving a slight panoramic effect to the images. Although Dwayne’s scanned these images at a size of 1312 x 1546, I think extra detail could be extracted from the negatives using a better scanner. I may have to revisit these scans if I ever gain access to a better scanner.

Edit (2/9/2019): It took me damn near forever, but I finally had a chance to shoot some real 127 film in the Yashica 44. When I first published this review in October 2016, I had done the modifications to shoot 35mm in it, and thankfully I kept the parts safe so I could revert it back to original condition.

With some very expired Supre-Tone black and white film that was made in Germany probably in the late 1960s, I shot a whole roll in winter of 2018 and here are the results of what the camera can do using the full size of it’s film gate.

Although I quite expected the Yashica 44 to return great images on real 127 film, the real hero here is the ~50 year old film that held up wonderfully. With the Yashica’s excellent and reliable Copal shutter, I was able to shoot these images at around 1/30 of a second hand held wide open. I’ll have to take it out again soon, maybe even with some color, but I think it’s safe to say, whether you adapt it to use 35mm or shoot real 127 film, this is a special camera that makes great images!

In all, I was very pleased with the results of these images on both types of film. Using the Yashica 44 was my favorite experience ever using a TLR. It’s smaller size, 712 gram weight, and easier portability made for a much more enjoyable experience for me. Yashica made great full size TLRs and it’s good to know that they didn’t skimp on the “baby” Yashica 44. I actually really like the look of the sprocket holes and film data on the sides of each exposure. The first image in the gallery of the boy playing with Play-Dough is an awesome image that I think would look great blown up.

I will definitely revisit this camera again with better light seals, and I cannot wait to see what other images I can make with it!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://www.yashicatlr.com/yashica44series.html

http://feuerbacher.net/photo/Articles/Yashica44_35mm/Yashica44_35mm.html

https://photothinking.com/2019-01-25-yashica-44a-twin-in-small-package/

http://camerapedia.wikia.com/wiki/Yashica-44

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Yashica-44

http://dirapon.be/TLR127.html (In French, use Google Translate)

In 1958, a Sawyer’s Mk IV became my first good camera, bought at Sears, Roebuck for $89.95 with case. I used it heavily for many years and still have it. Handy size, lightweight, rugged, and very sharp lens.

One of the “better than box camera Kodak Brownie Six-Twenty” family cameras was a Yashica 44. It was the first serious roll film camera I used and learned much about f/stops, shutter speeds, and how to distinguish “cloudy bright” from “cloudy” conditions. Exposure guides came with every roll of film back in those days, which made photography under “other than perfect conditions” possible.

In time, I learned how to use a General Electric Selenium cell light meter, and “available light” photography was the next nut to crack when the light meter’s needle dropped to Zero. The 4X4 cm negatives and slides were smaller than the 6X6 cm “slices of reality,” but this wasn’t as interesting as the compact nature of the Yashica 44.

This came to halt one day, when the nut holding the focusing knob to the focusing rack assembly broke, and the camera was set aside. Could it have been repaired? There wasn’t much of the threaded post left, since most of it was still on/in the nut. I moved on to the Rolleicord V and 120 film, which is still in the film camera collection. Roll film TLR cameras have been described as “mini view” cameras and quite usable once the “left is right and up is upside down” working style is adopted. These days, roll film TLRs are used as “street photography” cameras that hardly draws attention from passerby, since it “looks like a toy camera” in the digital age.;)

The Yashica 44 models seem to have a stronger following than many of their full size 6×6 TLRs. I wonder if it’s because there was so much competition in the full size TLR world, and not as much with 4x4s. Other than the obvious choice of Rollei, I know that a few other companies like Ricoh, Primo/Sawyer’s, Walz, and a few others made them, but the Yashicas seem to be the most commonly found. If 127 film was more easily available these days, I would definitely use it much more. As it is, I do have a moderate supply of usable 127, but I like to sparingly use it as I find other 127 cameras to try out.

After reading your great lengthy article about the Yashica 44, it makes me want to dig my 44a out and try the 35mm adaptation. It’s getting harder and harder to find 127 and I’m down to only one roll of Efke left. Great work!