This is a Leica M3 35mm rangefinder camera, built by Ernst Leitz GmbH from 1954 to 1966. It was the first Leica that used the Leica M lens mount, the first Leica with a coincident image rangefinder, and the first Leica with a wind lever. It is considered by many to be one of, if not THE best camera ever made. It is a precision instrument built to the highest quality standards. So high, that many M3s still work today as good as the day they were made. It is one of the most popular cameras ever made and as such, used models can exceed well over a thousand dollars on the used market.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: Leitz Wetzlar Summicron 50mm f/2 coated 7-elements

Mount: Leica M-mount

Focus: 1 meter to Infinity (this dual-range version can focus as close as 478mm with optional attachment)

Type: Coupled Rangefinder

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Coldshoe and M and X Flash Sync

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/leica_pdf/leica_m3.pdf

Prologue

This review is one of the more difficult ones I’ve written. It’s a camera I never thought I would ever have a chance to review. For one, Leica M3s are still very valuable. Sold prices on eBay generally range from just under a thousand dollars to several thousand depending on what else is included with the camera. My typical budget for the cameras reviewed on this site is around $20 – $30. Many have been given to me for free, or were ones I bought in a lot with other cameras that I sold, reducing the total cost to $0 or even less. But also, there are countless reviews and posts on the web with a wealth of information about the Leica M3. There is very little that I could say about this camera that hasn’t already been said countless times before.

I had the chance to review this Leica M3 because it was loaned to me from a neighbor. He said he bought this camera in the 1970s from a camera shop and he used it to record his 4 children growing up. This camera has been used countless times over the years to record birthdays, anniversaries, family vacations, and every day general life, and now it’s my turn to give it a shot.

I only had the camera in my possession for a couple of weeks and as I write this review, I have already returned it to him. What follows will be my best attempt to share my thoughts and results while still offering some unique information you can’t find elsewhere.

History

If you were to take any single product ever made in the entirety of human history and find one that has had more of a greater influence on everything that followed it, you would be hard pressed to find one that had as great of an influence on it’s industry than the first Leica camera.

Leica is the brand (and company) that has been copied, cloned, mimicked, replicated, and inspired the most out of any single product or maker ever in any industry.

Leica is the brand (and company) that has been copied, cloned, mimicked, replicated, and inspired the most out of any single product or maker ever in any industry.

It’s this notoriety that has given Leica a legendary place in the history of photography. Perhaps even more amazing is that their reputation survived two world wars, two German economic collapses, the rise of the Japanese camera industry, the advancement of electronic and CPU controlled cameras, and the digital camera revolution. Leica is still a respected brand, and a name that when mentioned within earshot of any photographer, will cause them to take notice.

You can figuratively throw a rock on the Internet and find some kind of Leica information site on the web. A Google search for “Leica History” will tell you anything you could possibly ever want to know about the Ernst Leitz company, their earliest products, every model they’ve ever made, and how well they’ve done over the past century, so I’ll try not to repeat too much information here.

What follows will be my very best attempt at a Cliff’s Notes version of the history of the Leica camera…

In 1849, German mechanic and mathematician Carl Kellner published a paper describing a new optical formula he had developed in the field of microscopy. His new formula was capable of rendering an image with correct perspective, free of the distortions typical of other microscopes of the time. Herr Kellner went on to start the Optisches Institut in Wetzlar, Germany which was an optical institute that made lenses and other equipment for microscopes.

A 21 year old mechanic named Ernst Leitz would move to Wetzlar and become employed at the Kellner Institute in 1864. Leitz had several years of experience making watches in Switzerland, so shortly after starting at the institute, he would be trained as an instrument maker for physical and chemical apparatus.

Leitz must have done a pretty good job, as he was promoted through the institute quickly, and in 1869 became the sole owner of the institute, changing the company’s name to Ernst Leitz GmbH.

Leitz continued pioneering work in the optics industry, focusing mainly on microscopes for medical use. The company earned a high reputation for well built, quality products. Many of their early products were custom tailored for each customer’s specific needs, assuring that very few of these early microscopes were alike.

The company grew quickly, and by 1887 had produced it’s 10,000th instrument. Within 4 years, that number doubled, by 1899 the 50,000th was made, and by 1907, the Leitz company had made it’s 100,000th microscope.

By the turn of the 20th century, Leitz had a positive world-wide reputation, and had expanded it’s product offerings to more than just microscopes. The company was a pioneer in labor practices, establishing an 8 hour work day, and company sponsored health care for it’s employees.

In 1902, a German mechanic and industrial designer named Oskar Barnack started work for Carl Zeiss in Jena as a precision mechanic. He was well known in the German optics industry and helped Zeiss expand out of optical lens manufacturing into the photographic industry. Another Zeiss employee, Emil Mechau, had left Zeiss to work for Leitz in 1908 as there was more creative freedom working for Leitz. Around 1911, upon hearing of his friend’s dissatisfaction working at Zeiss, Mechau recommended to Leitz that Barnack would make a good addition to the company.

Impressed with his reputation and recommendation by Mechau, Oskar Barnack was recruited by Ernst Leitz to work for him and was offered the head research position for Leitz’s microscope division.

Despite being a skilled mechanic and industrial designer, in his free time Barnack was an enthusiastic photographer. Around 1912, he was tasked to work on a new aluminum bodied motion picture camera that would use 35mm cinema (or kine) film. Oskar Barnack had severe asthma which made him weak, and the aluminum body was chosen to keep weight to a minimum, compared to the heavy wooden cameras of the day.

While working on this new motion picture camera, Barnack often struggled to get the shutter timings right because film emulsions of the day were very inconsistent and often required varying speeds to get the exposure correct. Since cinema film came on very long spools, if the timings weren’t correct, a whole roll of film could be wasted if the exposure was incorrect. Barnack set out to develop a type of film tester that would expose a single frame or two of a new roll to test it’s speed, and once he could determine the correct timings for that roll of film, he could calibrate his motion picture camera to expose the rest of the roll consistently.

Barnack’s first prototype of his single frame tester was completed in 1913 (some sources say 1912, but I believe 1913 is correct). Upon it’s completion, Barnack’s tester had no official name, but in the years that would pass, this original device has earned the name “Ur-Leica”. The prefix “ur” in German means prime, original, or first.

The Ur-Leica was designed to use the same 35mm cinema film that would have been used in cinema cameras, but in order to increase the exposed image size, he made it so the film would travel through the camera horizontally, which doubled the size of the exposed frame resulting in images that were 24mm x 36mm.

Even though it wasn’t his original intent, the Ur-Leica turned out to be the inspiration for the first Leica still frame camera. By 1913, the idea for a still frame camera that used 35mm cinema film was not new. Prior to Barnack’s tester, other manufacturers such as C.P. Goerz and Ernemann had already designed models that did the same thing. There was no set film standard for motion picture film at the time, so early 35mm still frame cameras often relied on paper backed unperforated motion picture film that was shortened and loaded into custom, hand built 35mm cameras. These cameras fed the film vertically, just like cinema cameras would have, producing an exposed image size of 18mm x 24mm, exactly half of Barnack’s tester.

Oskar Barnack was said to be impressed with the images made from the Ur-Leica, and saw the potential for a new type of still frame camera shooting “double sized” 24mm x 36mm images. It’s small size meant it would be easily portable, and when combined with a quality lens, would be capable of highly detailed images that would enlargen well. Despite the promise of what a new still camera could offer, the idea to mass produce the camera would not materialize for nearly a decade.

There were multiple reasons for this. The first being that Leitz was a world leader in the microscope industry, and while cameras might have been a logical branch for the company to pursue, it’s demands for current products limited the amount of resources that could be given to a new camera department. But more significant was the onset of World War I in Germany which halted a lot of German industry, and by the end of the war, had decimated the German economy. Further complicating matters, the senior Ernst Leitz would pass away in 1920, and the entire operation of the company would pass onto his son, Ernst Leitz II.

By 1923 however, the Leitz company recovered enough to allow Barnack to convince Leitz II to allow him to use his 1913 prototype to manufacture a limited run of 25 (some sources say 31) cameras that could be given to photographers to test. Although these prototypes were never sold or given any kind of “official” Leica name, in the world of Leica history, these first cameras have become known as the Null Series or sometimes as the Leica 0.

The Null Series cameras must have received enough positive feedback that in 1924, Leitz allowed for a limited production run of 1000 Leica cameras. The name Leica was chosen as a combination of “Lei” from Leitz, and “-ca” from camera. The practice of combining a part of the company name with “-ca” was common in the early years of the Japanese camera industry with names like Yashica, Nicca, and Konica.

The new Leica camera was revealed in 1925 at the Leipzig Spring Fair in Germany as the Leica I. The camera was an immediate success as it was the first ever compact camera designed for 35mm cinema film made with top notch quality, by a reputable optics company as opposed to some hobbled together model built with very low quality control standards.

The first Leica I had a cloth focal plane shutter with speeds from 1/25 – 1/500, a fixed scale focus viewfinder, and a non-removable, but collapsible Leitz 50mm f/3.5 lenses. The lenses available on these early cameras changed from a simple Leitz Anastigmat, to an Elmax, finally settling on the Elmar.

The Leica I had several minor revisions to it’s design over the next few years, but in 1930 was upgraded to allow for interchangeable lenses, using a 39mm screw mount. This 39mm screw mount became so successful that it earned the nickname Leica Thread Mount, or LTM for short.

In 1932, an all new model, called the Leica II was released with a coupled rangefinder added to the body of the camera. The rangefinder was not integrated into the main viewfinder, but was instead visible in a second window next to the main viewfinder. Although primitive today, this was revolutionary stuff at the time as the only rangefinder aides at the time were auxiliary ones that were used completely separate from the camera, or attached to an accessory port.

Both the Leica I and II were huge successes all over the world. While Leitz had enjoyed a very positive reputation as a leader in the microscope industry, it was the Leica camera that would elevate the company to levels never before possible.

The film used in both these early cameras was bulk cinema film that a photographer could spool him or herself using large spools of uncut cinema film and then load into custom Leitz film canisters. While this was an acceptable method for loading film in 1932, the photographer would have to cut and spool his film in a dark room, and loading the camera required very low light so as not to accidentally expose the film.

In 1934, the Eastman Kodak company out of Rochester, NY would release an all new format of 35mm film that came pre-loaded in metal canisters which they would refer to as 135 format film. This film was designed from the very beginning to be fully compatible with both Leica cameras, and the Contax camera which was a competing model made by Zeiss-Ikon.

Kodak would release it’s own line of German built 35mm cameras called the Retina series, which were the first cameras designed specifically for this new 135 format film, however the basic specifications needed to match the Leica I and II’s body, because Kodak knew that in order for it’s new film to have a chance to succeed, it had to be compatible with the world’s best selling cameras.

Eliminating the need to custom cut your own cinema film and allowing for subdued daylight loading, Kodak’s 135 format 35mm was an immediate success. But it also had the side effect of making the Leica even more popular as well, since the film was easier and safer to load without a darkroom.

The Leica line would continue to evolve with the Leica III in 1933, which added a front-mounted slow speed dial which brought the slow speeds down from 1/25 to a full second. The Leica IIIa from 1935 bumped the top speed up to 1/1000th of a second.

These early Leicas set the standard for the world’s best cameras of the 1930s. Prior to the second World War, Leica had become so synonymous with quality, that many copies, first from the Soviet Union started to be made. Although the Soviet copies were never branded as actual Leicas, they were screw for screw identical to the original.

After the war, all of Germany’s patents became null and publicly available to anyone who wanted a crack at making a camera using any part of the design from a German company. Cameras that ranged from exact copies to those just heavily influenced by the Leica came in many shapes and forms from the Soviet Union, Japan, England, the US, and several other countries. While most Soviet made Leica copies were identical to the original design, the more successful and better built Japanese Leica copies were heavily inspired by the original Leica, but almost always had something distinctly different. Canon gained their reputation as a quality maker of cameras by first copying the Leica and improving upon it. As the years went on, these original Leica copies would end up developing into their own distinct models that would eventually look less and less like a real Leica.

Thankfully, the area of Germany where the Leitz company was located was in what would become Allied controlled West Germany, and Leitz’s operations were allowed to continue. Despite having all of their designs and patents copied by many companies all over the world, Leitz kept innovating. For the first few years after the war, they would continue to update and improve the pre-war models with new and unique features.

Perhaps due to the widespread use of Leitz’s designs, in 1954 the company would release it’s first completely new camera designed from the ground up. Known as the Leica M3, (there was an M1 and M2, but they came after the M3) this new camera offered a fresh start for the company. The M3 had an all new body with a bayonet lens mount, which would become known as the Leica M-mount. Bayonet mount lenses offer many advantages to screw mount lenses, the most significant being they are faster to attach and detach. The Leica M-mount was so successful that it is still in use today with digital Leica cameras. Variations of a bayonet mount are still commonly used by Nikon, Canon, Pentax, and many others today.

The M3 also had a combined, coincident image rangefinder which meant that a secondary image was projected into the center of the main viewfinder window, allowing a photographer to see focus, and compose his shot without having to move his eye from one window to another. Although the M3 wasn’t the first camera to have this feature, it was arguably the one that implemented it the best as the M3’s rangefinder window was larger, brighter, and easier to use than any other model that came before it. In fact, the M3’s viewfinder was larger and brighter than those found in many rangefinder cameras made decades later, including some future Leicas!

The M3 was chock full of other innovative features like a double-stroke lever film advance, glass film pressure plate, automatically adjusting frame lines, parallax correction, and a single combined shutter selector with both fast and slow speeds.

The M3 was in production for 12 years. By the time the last models were made in 1966, over 220,000 had been made. That number may not seem impressive when compared to other popular cameras like the Argus C3 or other long lived models, it’s pretty amazing when you take into account that the M3 was an extremely expensive camera aimed at the high end of the market. For nearly a quarter of a million to have been sold over that long of a period of time was a huge achievement.

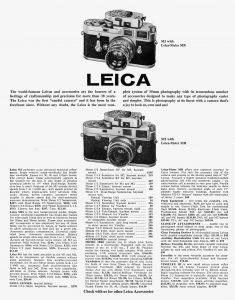

A 1960 catalog for Webbs Camera in San Jose, CA lists the Leica M3 selling brand new for the following prices (2016 prices adjusted for inflation in parenthesis):

- Body Only – $297.00 ($2,421.68)

- w/ Elmar 50/2.8 – $363.00 ($2,959.84)

- w/ Summicron 50/2 – $447.00 ($3,644.76)

- w/ Summilux 50/1.4 – $513.00 ($4,182.91)

It’s worth mentioning that all of the above prices are MSRP, and it was very common back then for shops to sell cameras at prices far below MSRP, but still, when you take into account that the “average” M3 with Elmar 50mm f/2.8 lens sold for the equivalent of nearly three thousand dollars today, that puts it in the realm of Nikon D810 or Canon EOS 7D Mk II DSLRs with their associated kit lenses.

The image to the right shows a page from the Webbs catalog showing prices of many available lenses and accessories that could be purchased with a brand new M3, further increasing the price. A photographer with deep enough pockets could very easily exceed $1000 in 1960 (over $8100 today) with a couple extra lenses, ever ready case, meter, and a flash unit.

Despite my best efforts to keep this history section as brief as possible, I still managed to ramble on quite a bit, so I won’t continue with too much more Leica history other than to say that the M3 was far from Leitz’s best selling or most popular model. The M-series has remained popular to this very day. The most recent model is simply called the Leica M and is a full frame digital rangefinder with a 24MP sensor and a 3″ live view LCD screen on the back.

Today, the Leica M3, like all Leicas are extremely popular with collectors and photographers alike. Many are still in regular use today, and many more sit on the top of their respective collector’s shelves. With few exception, nearly every camera ever made to adorn the name “Leica” is worth a substantial amount of money.

Their reputation is so great, that it actually turns some photographers and collectors off because when it all comes down to it, a Leica is a luxury item, in the same way a Rolls Royce or Bentley is a luxury car, or a Rollex is a luxury watch. You can certainly accomplish the same basic tasks with a Chevrolet or a Timex, but not with the same level of opulence.

At one time, I said I would never review a Leica camera on this site because they are so far from my budget that I knew I would never afford one. I still can’t afford one, but was fortunate enough to receive this M3 on loan from a neighbor.

My Thoughts

The Leica M3 is a great camera. It is solidly built and everything about it feels precise, sturdy, and well connected. The serial number of the model I reviewed suggests it was made in January 1961, the peak of the M3’s popularity. This camera is 55 years old and other than some dust and a bit of grime, feels like it could have been made yesterday. The tolerances of all the parts are very tight. The shutter fires with a purposeful snick. The viewfinder is bright and easy to use. The motions of the camera are precise and elegant. The focus and aperture rings on the lens turn smoothly and without resistance. The film transport had an almost fluid like smoothness to it.

If I had to pick my favorite thing about using the M3, it would definitely be the viewfinder. I had heard many good things about the M3’s viewfinder, but it wasn’t until I actually peered through it that really understood what all those people were saying. I was blown away at how large and bright everything was. Considering this camera was built nearly 20 years before some other rangefinders in my collection, the rangefinder patch on the M3 puts others to shame. Later Leica M-series cameras didn’t have as bright of a viewfinder as the M3. In addition to it’s brightness, the viewfinder has a 0.92x magnification ratio which means that objects seen through the viewfinder are nearly life size. This means you can focus the camera with both eyes open, a trick that allows a skilled photographer to compose and focus simultaneously.

The large and bright viewfinder changes my perception of how good a coincident image rangefinder could be. When I look through the dark, small, and yellow rangefinders like those found in the Yashica Lynx, or the Konica Auto S3, I wonder why those companies couldn’t have copied Leitz just a little more!

My least favorite thing about the M3 was loading film. This was something I had anticipated prior to touching the M3, and overall, it is not really that hard, but it does require a bit of patience as you need to remove the bottom plate of the camera, pull out the take up spool, and attach the film leader to it prior to putting anything back into the camera. If you are not used to a bottom loader, it can be intimidating the first time. On the plus side, Leica wisely included a door on the back of the camera that can be opened with the bottom plate removed which allows you to see the film load onto the spool. This allows you to make sure the leader has correctly lined up with the take up spool and sprockets prior to closing the camera.

Prior to writing this review, I thought to myself what could I possibly add to the Leica M3 discussion that hasn’t already been said a million times. After all, I am just one guy, and this is just one M3 that I borrowed from a neighbor and I shot a grand total of 2 rolls of film in it. If this were some obscure camera made in Czechoslovakia in small numbers, I might be qualified to make some conclusions about the camera for the benefit of others who may have never seen that model before, but that’s not the case here. The Leica M3 is a very popular camera, and many people have shot them many times over the course of many years.

So rather than continue to bore you with my thoughts, I thought I would try something new and solicit some feedback from other M3 users in the Vintage Camera Collector’s group on Facebook.

Your Thoughts

I made a post in November 2016 soliciting some feedback from various members of the VCC group regarding their thoughts about the Leica M3. I stated that I only wanted people with first hand experience, and not those who have never actually shot with one. I felt that by hearing from actual users, I might uncover some interesting stories.

I made it clear to these members that I would use their words in an upcoming review and that by them sharing their stories with me, that they were giving me their permission to reprint their words on my site. With that in mind though, if anyone reading this site objects to anything I have shared below, please let me know and I will remove it.

Ivan A Sanzana I fell in love with the M3 when I was a kid living in Patagonia, there was a friend of my father who had emigrated from Germany after the war, Hans Melzer was his name he drove a Land Rover and was a Master Diver, I remember him well, he had a silver Leica camera and took tons of photos of everyone in the small town, we have several photos of him holding his camera. Later when I came to live in California I came across a Leica M3 which reminded me of Uncle Hans, I have a few silver M3’s now and love to take photos of everyone and people know where the Dream of owning one came from. I like that it is mechanical, no batteries, it feels great to the touch and the photos come out with a certain sharpness and patina, especailly Black and White.

Ken Hough Sometime about 1976 I had the opportunity to use an M3 for a summer to shoot weddings. I had shot a wedding with one of my first Nikons and I could hear the echo of the shutter every time I fired it off. A friend who was a member of the wedding party heard my camera every single time I shot it. He came up to me during the reception and suggested that I borrowed his M3. I did and he let me keep it the summer since he had one or two others. When I needed to shoot with a wide angle lens it needed those goggles and I thought that was kind of a funky thing to do. As far as the reliability it was my own fault if I had an over exposure so you can’t comment on that. It was a fun camera to use.

Alan Starkie I own one and I repair them all the time so get to know them rather intimately. It has a certain status, perhaps cult and maybe it isn’t the best of the bunch. I suppose I prefer the M4 with it’s ‘jaunty’ rewind knob, that I think from a design point of view is very stylish. I prefer the M4 because I can easily use a 35mm lens but those are relatively minor points because the M4 came afterwards – it isn’t the ‘daddy’. When I was a kid, I had a picture of an air-cooled 911 on my bedroom wall. Who wouldn’t like one of those? If it were a camera it would have been an M3 🙂

Jim Shulman The M3 (an example produced in 1961) with a second-generation 50mm Summilux is my everyday camera. Most Leica fans go for the 35mm lens as their standard; I’m more a fan of the 50, particularly the Summilux, which has it’s own special look. I love the camera’s ruggedness and utter simplicity: all the controls are manual, and there are only four variables: shutter speed, aperture, focus and film sensitivity. After you master those, you just concentrate on the picture. I love the frame lines, and composing the picture while seeing area OUTSIDE of the frame. After a while everything just feels intuitive. The shutter is very quiet, and the build quality incredible. Some annoyances are the bottom loading, the all-black take up spool, which is a beast to thread in low light (though I found a $1 hack for that), the lack of a rewind crank (though there are aftermarket cranks that fit neatly over the rewind knob, and the lack of a shutter release lock (put in away for a while, and you’ll inadvertently snap an empty frame when you’re ready to shoot again. Yes, I know you can always put it away with the shutter uncocked, but it’s almost reflexive to wind after every shot!) It’s also a surprisingly heavy camera (try picking up an Nikon S2 after using the M3!)

John Fleshin The feel of the camera, and the fact that you can see around the frame lines is the mark of RF shooting, along with the quiet shutter– glass is good, do you have the rest of the dual range? Very interesting lens– and I also have an M2, with M4 finders– the fact that folks are using these for so many years post build speaks volumes. The body size and shape – well, they got it right– and current production cameras of several marques are made to a similar layout. I prefer the double stroke , I think it is faster.

Mike Novak I have had an M4 for longer than the M3, which was a recent purchase. I thought that I would never own a better rangefinder than the M4, but now I am not so certain. Why I feel that way is difficult to quantify, as the M4, from the perspective of a user, is a better camera, easier to load, and better to use with a 35mm lens. Yet I keep grabbing the M3, there is just something about the way that it feels in my hand that makes me want to take photographs. It feels like a camera should, it carries the weight of history, a Leica M3 with a 50mm Summicron lens will always be THE 35mm camera to me. One look through that huge blue viewfinder and I was hooked.

Eric Kaas Sluis I first touched the M3 in Munich many years ago when I was an apprentice with my teacher, he gave it to me and it was like magic, the feel, the touch, the mechanics, everything. He gave me roll of film and send me out. “Make pictures” and that’s how I started. I later moved to SLR’s and went my way. Until one day I received a message that read; “I like your photo’s a lot, I will send you a present”. I didn’t know the individual but he must have seen my work somewere in an Expo. Two weeks later I received a box through the mail with a M3, 35mm goggled Summaron a Hector 135 and a pop-up lightmeter, leather camera pouch. A note came with it; “Make it alive, it deserves it” ….. the camera was never used, I had it greased and CLA’d and have since used it aside my other RF bodies. One day, a deserving young photographer will receive it from me, in a package and I hope it will go on “living” in the hands of a person who will do beautiful things with it. Indeed a camera with a soul and a presence…

Jay Javier The feature I am most impressed with: view for the 50mm lens is near life-size. It’s so possible to compose with both eyes open.

Alan Crossley A wise Japanese collector/shop owner once stated that the double stroke Leica M3 is the best 35mm camera ever made …he maintained that the double stroke action did not put as much stress on the gears during forward advance and well that was his take but I thought about it. It goes deep with Leica…like Rolleiflex or Rolls Royce..it’s endless. “The art of moving a vehicle so quietly that one can hear the dashboard clock ticking at 100mph” – RR …Leica – “The pleasurable art of taking a picture that the shutter speed sounds like a love locket closing whilst bidding farewell on the platform of a train station during wartime”

Adi Taylor Owning and using m2/M3/m4/m5/m6ttl/MP/m9 I place the M3 at the very top, never have I used such a great camera, best viewfinder of all for 50/90, feels the most precise, even more so than the Leica serviced MP (don’t know how but it’s true)

Steve Ford Had a customer come in the shop today with an M3 and a Canon P. Sad to say, as much as the P is loved hereabouts, the M3 finder and rangefinder spot simply blew the P away in a rather substantial cloud of dust. I’m a specs wearer and I simply could not see the 35mm framelines in the P wearing my glasses, while in the M3 they were easily visible, and the spot was so sharp and clear. I was blown away by how big a RF viewfinder could be, how clear the patch could be, how sharp the image. That’s what makes it a classic for my money.

Colin Clarke I bought this M3 SS from a dealer as store demo model. It has travelled the world many times. It has exposed countless rolls of film. After 44 years of use, I got it a CLA in 2014 with Youxin Ye, just in case it needed it. It remains silky smooth. It is not just a camera. It is the how-to reference for designers. Drop the mike.

Tim Sassoon IMHO the best criticism of the M3 is that there’s no practical reason to build a 35mm film camera to last forever. Now, realize that I drive a 1979 Mercedes 300SD turbo-diesel with 333,000 miles on it when I say that 🙂 . But consider the Olympus OM series – or even the Leica CL. Many have lasted until now, but they weren’t specifically built to do so. They were intended to provide a decent service life at a decent price, and frankly, that’s what people who aren’t collectors want these days – a few or at most ten good years, then they’ll buy something different.

My Results

In late September 2016, I took my borrowed M3 to Parke County, Indiana where I shot some old covered bridges and a cemetery, and then again to a pumpkin patch in early October. I used a combination of Kodak Ektar 100 and Fuji 200 for these two rolls.

Looking through these photos, I can’t help but be impressed with their quality. Each of these images likely represent the best of what 35mm could do on any camera, but is there anything truly special about them that cannot be achieved on another camera? I honestly don’t think I can say yes.

I’ll likely get some flak from some people on what I am about to say, and this might come as a shock to some who are new to shooting film, but there is a limit to how sharp, how colorful, or how clear an image can look on 35mm film. The Leica M3 is a great camera, and the 50mm Summicron is a great lens. The thing is, if you were to recreate any of these images on a camera using other great lenses like a Zeiss Sonnar, Voigtländer Color-Skopar, Nikon Nikkor, Minolta Rokkor, Konica Hexanon, Yashica Yashinon, Asahi Super Takumar, or any of the countless great optics made over the past century, you simply will not see a difference.

So if you can likely recreate nearly identical shots with a ‘lesser’ camera, what is so great about owning a Leica M3 anyway?

The Leica M3 is a camera. All cameras are tools. Tools are things we use to accomplish a task. The task we aim to accomplish with a camera is making photographs. A Leica M3 is no more effective at making a photograph than a cheap plastic point and shoot, or a Holga toy camera is. But how you get there from a blank piece of film to a stunning photograph depends on which tool you use. When you use a Leica M3, you are using a tool that a whole lot of adjectives apply to. Quality. Precision. Smoothness. Reliability. Design. Perfection. OKay, maybe those aren’t all adjectives, but you get my point.

That last word, ‘perfection’ is the reason you buy a Leica M3. Leica set the standard for miniature 35mm cameras when they released the first Leica I in 1925 at the Leipzig Spring Fair. The world took notice. Then, after the war, after losing their patents to pretty much everyone, they went back to the drawing board and designed the M3. A camera so well designed, so effective, so perfect, that the world has been taking notice ever since.

At a glance, it is easy to mistake any of the M3’s “children” for the original. A casual observer would be forgiven if they didn’t notice a difference between an M3 and the M4. The Leica M7 from 2002 shares a very strong resemblance to the original M3 as well. Even the current generation Leica M digital camera still resembles that original design. As each new model was released, Leica never had to go back to the drawing board again, because they didn’t have to, much in the same way that Porsche has kept the same basic design with the 911 ever since it’s first model. Each new generation of 911 and M-series Leica had incremental upgrades from the one that preceded it, continuing to tweak and improve the formula to it’s current day form. Also like the Porsche, some people prefer one generation over another, but you’d be hard pressed to find anyone who can claim that the older models are significantly worse than the original.

With all this adulation I’ve thrown at the M3, the more important question that everyone at one time or another will ask themselves is, should I buy one?

That’s the harder question to answer and one you likely won’t get from me.

I’ll borrow a phrase from Hamish Gil’s excellent review of the Leica M3 and say that before buying a Leica M3, you must rationalize the purchase of an M3. After all, these are expensive cameras. A quick search of sold auctions on eBay for a Leica M3 w/ Summicron lens returns prices from as low as $800 to nearly two thousand dollars. The example I borrowed from my neighbor has the dual range Summicron, original metal lens cap, Summicron lens hood, and original leather ever ready case, all of which increase the price further. You could very easily buy as many as 20 or more Pentax K1000 SLRs with a 50mm SMC Takumar lens, 10 or more Nikon FM SLRs with a 50mm Nikkor lens, or even as many as 5 Canon 7 rangefinders with a 50mm f/1.8 lens for the same price as one Leica M3 with a 50mm Summicron.

It is very easy to get caught up in the overwhelming praise and constant hype regarding what many consider to be one of the best cameras ever made, and forget that the camera is not perfect. For one, the newest M3 was made over 50 years ago, and like all other 50 year old cameras, the perils of time can wreak havoc on the mechanics, the glass, the cloth curtains, or any other part of the camera. A Leica M3 may have inaccurate shutter speeds, leaky curtains, or a broken shutter altogether. The lens could have fungus, haze, or deep scratches. The body could have other conditional issues, like problems with the film transport, a dirty viewfinder, or other problems with the rangefinder rendering it unusable.

Leica M3s, despite their excellent build quality, are not immune from the need to be serviced from time to time, which costs money. If you are hoping to score an M3 for the lower end of the sold price spectrum on eBay, you should understand the risk that the camera could have issues, and you may need to have it serviced by a professional like Youxin Ye or Sherry Krauter who know what they are doing.

Other criticisms of the M3 are that it’s a bottom loader. While this shouldn’t be a deal breaker, it isn’t as easy to load as other cameras, especially in low light. It’s also a tad bit heavy for a rangefinder, and when dangling from your neck on an all day family trip to the zoo, you’ll definitely notice it’s there. Finally, some people just don’t like rangefinders and prefer other designs.

These criticisms are small however. Simply put, the Leica M3 is the best camera I’ve ever used. I enjoyed every minute of the time I had with it. I enjoyed looking at it on my shelf, and I would be lying if I didn’t fantasize about things I could say to my neighbor that would result in him saying “Oh, Mike, just keep the camera!” In the end, I returned it to him and thanked him for allowing me the pleasure to use it and write this review.

I would love to add an M3 to my collection, not because it takes better pictures, or because it does anything different than other cameras in my collection, but it’s just a damn fine piece of technology. A pinnacle in the history of human achievement. The Leica M3 absolutely deserves it’s reputation, and for those of you who are like me and could never afford one, you’re actually quite lucky because once you get a taste of one from a neighbor, it’s hard to give it back.

So back to the question, should you buy a Leica M3? I can’t answer that for you. I can’t even answer it for myself. After all, it’s just a tool. Tools need to be used by people who know how to use them. The M3 gives you everything you need to capture birthdays, anniversaries, family vacations, and every day general life to the best of your ability, and you can’t put a price on that.

Is the Leica M3 the best camera ever made? Probably not. Is the Leica M3 one of the best cameras ever made? Definitely. But don’t take my word for it. There’s over half a century of evidence that proves I’m right.

My Final WordHow these ratings work |

The Leica M3 is that rare example of something that has a sky high reputation and is deserving of it. This camera set the standards for design and functionality, and has been a very popular choice among photographers for over half a century. It has the best viewfinder on any rangefinder that I’ve ever seen. The viewfinder is so large, bright, and easy to use, it actually lowers my opinion of other cameras in my collection now that I know what is possible. The camera is pleasure to use, looks great on a shelf, and makes excellent photographs. Although I could come up with a few nit picks about it, the single biggest criticism I can offer of it, is that with it’s sky high reputation, comes a sky high price. Photographs shot with an M3 won’t automatically look better than those shot with other quality 35mm cameras. This is a luxury item that does it’s job with near perfection, but at the end of the day it is just a luxury item. You will pay more for a Leica M3 simply because it is, a Leica M3. If bang for your buck is something that is important for you, look elsewhere. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 30% | |

| Bonus | +1 for indescribable cool factor, handling, and quality | ||||||

| Final Score | 15.3 | ||||||

Additional Resources

I don’t normally editorialize the links in these reviews, but this first review by Hamish Gil, is one of the best reviews I’ve read for any camera ever. His pragmatic approach at rationalizing buying an M3, along with his fine writing skills make for a very enjoyable read.

http://www.35mmc.com/02/02/2015/leica-m3/

http://www.kenrockwell.com/leica/m3.htm

http://www.photoethnography.com/ClassicCameras/LeicaM3.html

http://camerapedia.wikia.com/wiki/Leica_M3

http://emanuelefaja.com/leicam3review/

https://cameraquest.com/classics.htm (Scroll down and look for the whole section of Leica M-series articles)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leica_M3

http://leicaphilia.com/category/leica-m3/

https://www.raylarose.com/words/leica-m2-leica-m3

http://www.dantestella.com/technical/m3.html

A fascinating read – I’ve been reading/writing about some this history stuff for another project I’m working on, so actually this has turned out to be a very useful post for me!

Thank you for the complimentary comments regarding my post too!

Thank you for this review, very complete. I have read some of it in other places, but never together in one site. I do have this camera and cannot let it go no matter what. It is an example of perfection in manufacturing and design detail. Just as the other Ms, this is one camera that every good photographer should own.

Thanks for this review. I visited your site after searching info about Canon rangefinders, and had just read where you said you would never buy a Leica M camera. Then I saw where you had a new review of one and I had to laugh, but then realized it was on loan to you. I also would like to have a Leica M2 or M3, but I am a poor man, and probably never will own own. I would rather seek out lower cost, well designed cameras to shoot with. Perhaps if I could rent a Leica for a week, it would satisfy my curiosity and I could move on. Even if I had one, I think I’d be too afraid to carry it around, worried I might drop it, or bang it into something. That would take the fun out of it for me 🙂

Ken, you and I are much alike. My entire collection consists of cameras I get for $30 and under, even free sometimes. On the rare occasion I spent a little extra (like my Kodak Medalist), I have never spent over $100 on a single camera, and you certainly will never find a Leica for $100! While the M3 is a wonderful camera that is awesome to use, has a great viewfinder, and has excellent lenses available to it, if you want a camera that’s 90% as awesome to use, makes equally excellent photos, but costs a fraction of the price, check out the Canon P. It’s still not “cheap”, but if you keep your eyes peeled, they do show up for $60 – $70 on occasion. Since you already seem to be a fan of Canon rangefinders, perhaps the Canon P is already on your radar.

Hi Mike! Indeed, we are a lot alike. I always wanted a good rangefinder camera, so after studying the Canons of the 1950s & 60s, I settled on either a Canon P or Canon 7. But then a Canon L3 body came up for sale that was about the same price, near $80, so I went for it. Then I realized the vintage Canon lenses are much more expensive than the bodies, especially the wide angle lenses. So I bought a 50mm Soviet Industar 61LD lens for under $20 (wow!), and I am very impressed with its sharpness. It will do for now. I have a photo of the camera here: http://www.instagram.com/rangefinder

The Canon L3 is a gorgeous camera and I am confident its every bit as good as the Canon P! I also, had decided on either the Canon P or a 7 early on and settled in with the P for the mere fact that while the 7’s are a bit more modern, and have the added benefit of a light meter (which may or may not work), they are also a bit less robust. Don’t get me wrong, Im not saying the Canon 7 is a cheap camera by any means, but if you hold a Canon 7 and a P (or your L3) side by side, the 7 will feel lighter and every so less “robust”. I think that Canon had started some levels of cost cuttin with the 7 series. Remember that by the time the Canon 7 came out, rangefinders were rapidly losing in popularity to SLRs, so Canon likely knew that they’d have to save money somewhere with the 7, even if it had some newer features. In any case, ANY Canon rangefinder from this era is bound to be an awesome camera.

Also, I agree that the Industar lens is a great lens and a hell of a value. If you ever have an opportunity to pick up a M39 Jupiter 8 lens, they’re a TAD sharper than the Industar, and have better aesthetics (if you care about that sort of thing). The Jupiter 8s are commonly found on Zorki rangefinders and can also be had for dirt cheap. Even if you never take that Industar off your Canon though, you won’t ever be disappointed with the images it makes!

I blundered on your site today and really have become engrossed in it. I wanted to let you know people are seeing this and appreciating the work you put in it. I especially liked your camera and shutter repair posts.

I am a camera collector with a lot of Leica screwmount cameras from the I to IIIg. I have a lot of lenses, rangefinders, filters, viewfinders, and even a MOOLY windup motor drive for my IIIb.

My prize is a null series factory replica made by Leitz to commemorate the early cameras. It’s similar to the Ur Leica but not as crude. You can tell it was intended as a test article. I also have some old Kodak 35s and a couple of Mercury 35mm cameras.

I just read your glowing review of the legendary Leica M3. I used to own one before it was stolen several years ago. It took very sharp photos but I mainly remember how heavy it was. It was like having a boat anchor around my neck compared to the light screwmount cameras.

I loved using the Leica screwmounts with all the fiddling that was needed to cut and load the film, set the f stops and shutter speeds, etc. They were fun and so classic. Like many, in the early 2000s I went digital, a lot of the reason being Photoshop. I could control the print instead of being at the mercy of photo finishers.

I still have all my Leica equipment and you are inspiring me to do film again. Last week I bought the new Olympus Pen F one of the reasons being it is so much like my Leicas. The Olympus is a great camera and is giving impressive images.

Now I can do both. Kodak is even bringing back Ektachrome.

I also used the Olympus OM-1n system from the 1980s to the early 2000s. I still have that outfit. I really liked that camera and its results as well.

Keep up the great work.

Jeff Oliveira

The Leica does not have 35mm frame lines in the viewfinder. They have 50, 90 and 135. Accessory viewing goggles or an auxiliary viewfinder are needed for 35 frame lines, or just use a leica M2 with 35, 50 and 90 frame lines. Top review nonetheless.

A legacy in 2007 enabled me to buy a 1955 Leica M3 double stroke body. I had a Jupiter 8 50mm f2 so I got a ring that did not activate either the 90 or 135 frame lines. I found a hood with a rubber ring in it that fitted on the end of the lens and I’m convinced this shading of the front element assists the lens to give of its best. My M3 can be described best as cosmetically worn. Brass peeks out at the corners and there are bright parts that have been polished by use. The vulcanite is fine with just a very small piece missing at one side. The mechanism is very smooth and everything works just fine.

It is a real pleasure to use. I already had a Weston V meter and a small Billingham bag carries my kit including films and a personal size Filofax for notes on my exposures. I’ve now spotted a very nice black leather Artisan and Artist strap on a dealers website. It’s described as used. Good. I would not embarrass my beloved M3 with a new accessory . Will purchase this next pension day. The M3 is 3 years younger than me. Last Christmas my partner bought me a massive book about Leica called Eyes Wide Open. I already had the 1936 book My Leica and I. In the latter, there is a contribution by an English doctor who has admitted in print that one day he took his Leica to bed with him! Well, he’s not alone. When I got my M3 I put it on my bedside table so I would see it when I woke up. My number is 782160 lens is 7546015. I use Tri-X rated at 500 iOS, negs scanned to disc. So, you see, my M3 is a digital camera. – “no no David, it’s not a digital camera as you don’t have to plug it into the mains every night to charge it up!,” ………………Ah?

This is a very interesting history and review of the M3. I used one for over 20 years. Mine was originally a double-stroke, but I had it converted to single stroke. I am now using an M2 because I often need a frame for a 35mm lens. Two comments:

I have read an alternate Leica history, that Mr. Barnack was intending all along to make a precision miniature camera to take on vacations of mountaineering. The use as a film testing device was not the original purpose.

You noted above, “Many people have commented that the 35mm frame lines in the viewfinder are hard to see, especially with prescription glasses.” The M3 has 50mm, 90mm, and 135mm frame lines. Are the people you cited referring to the M2, M4, or a newer model?

You’re right. Truth be told, I wrote this review almost 4 years ago and I don’t know what I was thinking back then. I have removed that sentence from the review. Thanks for pointing it out! 🙂