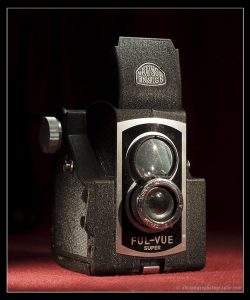

This is an Ensign Ful-Vue box camera made by Barnet Ensign Ltd. of Walthamstow, England between the years 1946 and 1949. This was the second camera named the Ensign Ful-Vue to be released, the first released in 1939 was a more traditional cube shaped box camera made by the original Ensign Ltd. The Ful-Vue was a simple, all metal camera with a single speed shutter and meniscus lens that had two ranges of focus depending on the position of the lens. The Ful-Vue was the best selling camera in England during and after World War II and remained in production for nearly 20 years.

Film Type: 120 roll film (twelve 6cm x 6cm exposures)

Lens: Unknown focal length (probably 75mm) uncoated single element meniscus

Focus: 3 feet to 10 feet extended, 10 feet to Infinity retracted

Viewfinder: Uncoupled Brilliant Reflex Finder

Shutter: Spring Tensioned Metal Blade

Speeds: Timed and Instantaneous (~1/30 sec)

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/pdf_files/ful-vue_guide.pdf

History

Ensign was the name of a London based company that made a variety of cameras and photographic supplies in the 1800s and first half of the 20th century. I’ll try to keep this short as there is a very thorough history of the Ensign company on Adrian Richmond’s Ensign Camera site. Ensign went through many name changes, acquisitions, and mergers over the years which causes their complete history to be a bit confusing. Rather than repeat everything here, I’ll try to come up with just a short summary, but if you’re interested to know more, I strongly recommend reading Adrian’s site.

Ensign was the name of a London based company that made a variety of cameras and photographic supplies in the 1800s and first half of the 20th century. I’ll try to keep this short as there is a very thorough history of the Ensign company on Adrian Richmond’s Ensign Camera site. Ensign went through many name changes, acquisitions, and mergers over the years which causes their complete history to be a bit confusing. Rather than repeat everything here, I’ll try to come up with just a short summary, but if you’re interested to know more, I strongly recommend reading Adrian’s site.

Ensign got it’s start in 1836 when two men, George Houghton, and a Frenchman named Antoine Claudet opened a glass warehouse in London. The company was called Claudet and Houghton and they specialized in all forms of sheet glass and that for optical products. The company continually increased their product offerings over the next 3 decades, eventually becoming one of the largest glass suppliers in all of England.

In 1867, George Houghton’s son joined the company and Antoine Claudet died, which resulted in a name change to George Houghton & Son. The new company would continue to expand it’s product offerings beyond glass, expanding into new markets, including photographic supplies. In 1903, George Houghton & Son introduced it’s first photographic film, which they branded as Ensign Daylight Loading Film.

In 1867, George Houghton’s son joined the company and Antoine Claudet died, which resulted in a name change to George Houghton & Son. The new company would continue to expand it’s product offerings beyond glass, expanding into new markets, including photographic supplies. In 1903, George Houghton & Son introduced it’s first photographic film, which they branded as Ensign Daylight Loading Film.

In 1904, Houghtons would acquire 4 different camera companies, Holmes Bros, A.C. Jackson, Spratt Bros., and Joseph Levi & Co., and would become a Limited company known as Houghtons Ltd. The patents and expertise of these 4 companies allowed Houghtons Ltd to become a major supplier of optical glass, film, and cameras in the early part of the 20th century, employing over 1000 people at all of their locations combined.

In 1915, Houghtons Ltd would acquire W. Butcher and Sons Ltd. and would be known as the Houghton-Butcher Manufacturing Company furthering expanding their product offerings and manufacturing prowess. In 1930, Houghton-Butcher would rename itself to match the name of it’s products, and would become Ensign Ltd. During this time, Ensign Ltd had a variety of cameras, from simple box cameras, folding cameras, and a miniature camera called the Ensign Multex.

In 1939, they would release a new box camera called the Ful-Vue. The Ful-Vue was a simple camera with a large brilliant viewfinder on top with a large viewing lens that was said to be bigger and brighter than any offered by any other company up until this point. The Ful-Vue was very popular with amateur photographers, and was often purchased for children due to it’s simplicity.

During the war, Ensign’s company headquarters was destroyed by German bombers. In 1945, the company would merge with a company called Elliott & Sons Ltd who produced a film brand called Barnett. The new company would then be known as Barnett Ensign Ltd. It was during this period that the second generation Ful-Vue being reviewed here was created.

The new Ensign camera had a radically updated body design, eschewing the simple cube shaped box of the original model. The new design of the Ful-Vue polarized people, some heralding it as an attractive and modern looking camera, and others who found the odd shape ugly. As it would turn out, more people liked it than didn’t because it would go on to be the best selling British made camera of all time. The second generation Ful-Vue had a stamped metal body with a crinkle paint finish. Although most were black, the Ful-Vue was available in at least three other colors, Gray, Blue, and Red. It had the same large brilliant finder of the first model, a single speed 1/30 shutter, fixed f/11 iris, and an extendable lens tube which allowed for close-ups and group shots to be taken.

The Ful-Vue was updated in 1950 with flash synchronization, three different focal distances instead of two, and a plastic front panel and officially given the name Ful-Vue II,

Finally, in 1954, the Ross-Ensign Ful-Vue Super was released which had a revised cast metal body, a folding hood around the viewfinder, a removable back for easier film loading, and a red exposure window with a sliding cover. The Ful-Vue Super also now supported Kodak’s 620 film format, instead of 120 like all previous Ful-Vues. The Super model was in production until about 1959 with a total production run of over a million units.

There was one additional model released in 1957 that bore the “Ful-Vue” name called the Fulvueflex. It was physically larger than all previous models, supported 120 film, and was made entirely of plastic. Other than the name and having a brilliant viewfinder, the Fulvueflex is considered by many to be it’s own separate model. It was not produced for very long and is very hard to find today.

If you live in the United Kingdom, anyone who was alive during the late 40s and the 50s will fondly remember the Ful-Vue series as a very common camera for children, families, and amateur photographers. The Ful-Vue is analogous to the Kodak Brownie in that it was an inexpensive camera that was very popular for amateurs. Outside of the UK, the Ensign Ful-Vue is a curiosity, a unique looking metal camera made in England that looks like nothing else out there. As a result, the Ful-Vue can be quite popular for collectors. As it is nothing more than a simple box camera, prices are often pretty low, but availability outside of the UK can sometimes be problematic.

As I write this review, a search for “Ensign Ful Vue” on eBay returns 5 for sale in the US, of which 1 is a Super, 1 is the original model, and 3 are either the new Ful-Vue or Ful-Vue II. If I expand my search to Worldwide, another 16 come up all of which are for sale in Europe. So, for US collectors like myself, this might not be a particularly valuable camera, but to get it shipped can sometimes cost more than the price of the camera itself. Still, the Ful-Vue is a camera that looks like no other, and is a historically significant camera since it was the best selling English made camera ever, so for that reason, I think it is absolutely worthy of being in any collection.

My Thoughts

I remember the first time I saw an Ensign Ful-Vue, it was sitting sideways on a table with a lot of other cameras for sale and I thought “What is that?” The shape of the Ful-Vue is certainly interesting and its not until you get a closer look that you realize that it’s a simple box camera with a brilliant finder, not unlike the Argus Seventy-Five. Unlike the Argus however, the Ful-Vue is an entirely metal camera with a pull out lens element which allows for closeups. Oh, and it takes 120 film, instead of 620!

I am uncertain if the Ful-Vue was ever exported to the US, but if it was, it had to have been done in small numbers as the number for sale here is pretty low. I had always thought the look of the Ful-Vue was interesting enough to keep on my radar. One day, my friend and fellow camera enthusiast, Mark Faulkner picked one up for his own site, the Gas Haus, and while talking to Mark about swapping some cameras, I asked if the Ful-Vue was available to be loaned, and he gladly sent it my way for a future review.

An advantage of borrowing a camera from a fellow collector is you can reasonably trust the condition of the camera when you receive it. True to Mark’s word, the camera worked wonderfully and was ready to shoot. The metal box has no light seals to crumble or replace and a quick inspection of the shutter revealed that it’s single speed worked fine and the glass was clear.

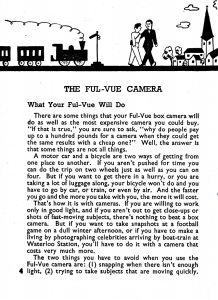

As I do with most cameras when I prepare to shoot them for the first time, I took a look at the Ful Vue’s user manual, which like many others is available on Mike Butkus’s excellent camera manual site. If there ever was a camera manual that I suggest reading, its this one. This manual is written much like a children’s book, in a casual tone with the occasional tongue in cheek humor. Filled with black and white illustrations and humorous anecdotes, the author suggests that the Ful Vue can do many of the same things as cameras costing hundreds of dollars more, much like riding a bicycle and driving a car can both get you from point A to point B, depending on the circumstance. As a person who greatly enjoys fun analogies, I applauded the author’s unique take on how you can make just as good of photographs with a box camera as you could with a much more expensive one. I highly recommend taking a look through this cameras manual, even if you don’t own one. Some of the concepts are really well written and apply to pretty much all cameras.

Another benefit of reading the Ful-Vue’s manual is that I learned of a feature I never realized it had. As it turns out, the front lens can be extended into a close focus position. Most inexpensive box cameras like this had a fixed focus lens that uses a small aperture that allows for everything from 8 or 10 feet to infinity to always be in focus. These other cameras almost always require some type of slip on auxiliary lens for closeups. Not so with the Ful-Vue, simply extend the lens to it’s outer most position and now everything from 3 to 10 feet will be in focus! I would be willing to bet that many people who have come across one of these cameras, and possibly even shot with one, never thought to pull on the lens to extend it and were unaware of this feature! I am glad I discovered this before shooting my first roll as I hope to take advantage of this feature. The two images below show the lens in both positions.

Loading film into the camera is quite simple. Like most box cameras, there is an outer part and an inner part that must be completely separated first. Unlike most box cameras however, the film compartment slides out of the side of the camera, and not the back. To open the camera, rotate the lock on the photographer’s left side of the camera and pull the right side out.

The film compartment has two spools, a take-up spool on the top, and the supply side on the bottom. In the image to the left, the takeup side does not have a spool, and the supply side has an empty spool in it. I would need to move the empty spool from the supply side to the takeup side before loading a new roll of film into the camera. If you’ve ever used a box camera, the process is exactly as you’d expect it to be. Even if you’ve never used a camera like this before, it’s pretty fool proof. Just make sure your leader is properly attached to the takeup side, and make sure the backing paper is facing outward. Once the film is loaded and is traveling smoothly from the supply to the takeup side, you slide the entire film compartment back into the camera’s outer housing, and twist the lock on the left side of the camera to secure it.

Before taking your first exposure, turn the film advance knob while keeping an eye on the red window on the back of the camera. Keep turning it until you see a number ‘1’ appear, at which point you are ready for your first image. Most films will give you some sort of warning right before the number 1 appears, so don’t panic if you feel like you’ve wound the camera several times without seeing anything.

The Ful-Vue is pleasantly compact, and despite it’s all metal body, isn’t very heavy. Weighing a scant 415 grams, it is only a bit heavier than a cardboard No.2 Kodak Brownie at 394 grams. The body is covered in a black crinkle paint finish that looks quite nice. The crinkle paint gives a flat look that resists smudges and finger prints, but also increases grip, making it easier to hold.

Like most box cameras, the Ful-Vue is designed to be held at waist level and composed through the large and bright brilliant viewfinder. The benefit to this type of finder is that it’s both very large and very bright, much brighter than those found on Twin Lens Reflex cameras. The downside though, is that the image you see through the finder does not reflect whether your image will be in focus or not. When looking through a brilliant viewfinder, everything will look like it’s in focus, even if the exposed image isn’t. The finder is also not parallax corrected, but this would only be an issue for closeup shots, which although technically possible, probably aren’t something you’ll likely want to try on a scale focus camera. If I had one nitpick to the viewfinder is that in bright and sunny environments, the lack of some kind of shield or hood, like those available on TLR cameras, caused me trouble seeing the viewfinder image clearly as the sun would wash out the image. The Ful-Vue Super which was released in 1954 had a hood, and I imagine that camera wouldn’t suffer from this same problem.

Aside from the pull out lens for changing the focal range, the only other setting on the camera is a slider for Time or Instant images. The use of the word “Time” is actually misleading though, as this mode functions more like a Bulb mode wherein the shutter will stay open for as long as you keep the shutter release pressed. Upon releasing the shutter release, the shutter closes. Typically when you see a “T” mode on a camera, the shutter will continue to stay open after letting go of the shutter release, which is not how it works here. There is no provision for a shutter release cable, so there is no way to lock open the shutter for a longer time, and there’s also no tripod socket, so your long exposures are limited to you sitting there with your finger holding down the shutter release, while the camera is resting on a table.

The shutter release is comfortably located on the photographer’s right side of the shutter, easily accessible by your right thumb. Travel of the shutter release is a tad long, so it might be a good idea to practice shooting the camera before you load in your first roll to get a feel for when is the exact moment the shutter will release. The shutter is a self-cocking design, so there isn’t any need to set the shutter before firing it. It will fire each and every time you press down on the shutter release. The Ful-Vue also lacks any double exposure prevention, so you must remember to advance the film to the next blank exposure after every shot, unless of course you intentionally want to double (or triple, quadruple, etc) expose an image.

Getting used to the controls and layout of the Ful-Vue is quite easy and something you’ll pick up within minutes of holding the camera. As the user’s manual suggests, this camera was designed to be as easy as possible to use. Despite it’s unique appearance, the camera works quite well. I thoroughly enjoyed using the camera and found it’s basic layout and lack of additional settings, allowed me to free my mind of any worry. As long as I was sure my subjects were the proper distance away from the camera and I had the right lighting, I was free to fire off the shutter at anything I liked.

Since the Ful-Vue was on loan to me, I didn’t want it to languish on my shelf while it awaited an opportunity to be used, so this spring I jumped at an opportunity to shoot it, and loaded in a roll of expired Kodak Portra 160 and took advantage of spring-time color. I enjoyed shooting with the Ful-Vue and went through the 12-exposure roll in a matter of 2 days. Normally I try not to rush myself shooting a camera the first time, but don’t feel as though I rushed anything. I just enjoyed it so much, it was very easy to get through the roll.

My Results

One of the appeals of shooting an old camera is how you have to think before each exposure. You need to carefully plan your shot, compose your image, and then use one of the camera’s (usually) mechanical speeds or f/stops. The process is slower and more methodical, but that’s part of the fun.

With a simple camera like the Ensign Ful-Vue that has a single aperture size and shutter speed, the process of thinking begins before you make your first exposure. It is critical with cameras like this to choose a film that will work properly with the camera’s limited settings. I rarely use any kind of light meter when shooting with my cameras, and instead rely on the old Sunny 16 rule. With Sunny 16, you are supposed to use a shutter speed that is the reciprocal of the film speed you’ve used.

The problem with a camera like the Ensign is that with it’s single shutter speed of 1/30, if I was going to use straight Sunny 16 without having to do math in my head, I’d have to use a film around ASA 25 or 32. These films still exist, but they’re not common, and usually expensive.

So, if you don’t have a film speed that correctly matches the shutter speed, you should choose a film that has a lot of latitude for over or under exposure. Black and White films are usually the safest bet as they almost always offer a superior level of latitude over color films. But I like color. In my experience, the color film with the widest degree of latitude is Kodak Portra. I happened to have a roll of expired Kodak Portra 160 in my drawer, so I thought this to be a wise choice for the Ful-Vue. The fact that it was expired meant that the Portra would need extra light, which should pair well with the Ensign’s single 1/30th shutter speed.

With my first roll of film, I shot some random things around my house and hoped for the best. I made a decision on several shots to try and extend the lens to take advantage of the “close-up feature.

When I got my negatives back and I got a chance to look at them on the computer, I was a bit underwhelmed. It didn’t help that I shot, developed, and scanned this roll back to back with the Voigtländer Brillant, another limited shutter speed box camera with a large brilliant viewfinder. The Voigtländer returned a whole roll with mostly excellent images that were sharp, properly exposed, and colorful.

The images from the Ensign Ful-Vue were a mixed bag, but after analyzing them a bit and tweaking levels in Photoshop, I could see that the images were better than I had originally thought.

Sure, there were some exposure issues, mostly in darker scenes like those in a cemetery or of the old house in the gallery above, But in brightly lit scenes like in the greenhouse, the dandelions, and the train images, things were quite a bit better. Sharpness in the center of the frame is pretty good. The images get a bit softer towards the edges, but not as bad as other single element cameras I’ve shot, which causes me to wonder if the Ensign really has a doublet or even triplet lens. I have found very little information about the technical specs of this camera. and in one article where someone took one apart to clean it, they left the taking lens installed, so there’s no way to count the individual elements. In the spirit of a simple and inexpensive camera, it probably does have a meniscus lens, but a very good one.

Strangely, in a couple of images where I attempted to shoot a close-up, I failed miserably. In the image to the right, I am positive I had the lens extended and the child was about 6 feet away from me, yet he is badly out of focus. I am not sure what went wrong here as I expected to get a good shot here. At least other attempts, like in the one of the dandelions, the results were much better.

I definitely enjoyed my time with the Ful Vue. The large and bright viewfinder is as large and bright in person as it looks in photographs. I wish it had a hood to ease shooting in bright sunlight, but otherwise the camera is very easy to use. As I said earlier, this is a loaner and I think I might drag my feet returning it to it’s rightful owner until which time I have an opportunity to try another roll of film to see if I can improve upon the weaknesses from my first roll.

Overall, the Ensign Ful-Vue is a really cool camera. It looks like nothing else out there, it has an impressive meniscus lens (assuming that’s what it really is), and the single speed and f/stop aren’t as limiting as you might think. Although most people probably buy these for their looks, since they use still readily available 120 film, there’s no excuse not to take one out and shoot some film through it.

My Final WordHow these ratings work |

The Ensign Ful-Vue was the most successful British made camera ever made. It is a unique looking box camera with a large and bright brilliant viewfinder that is very simple to use. During it’s heyday, it was very popular with children and beginning photographers. As a result, many people fondly remember these cameras from their youth, evoking a sense of nostalgia every time one shows up. They can be quite popular with photographers both for their historical value, but also their ease of use. From a user’s standpoint, the camera offers little more than a simple box camera, but that’s not the point. This is a cool looking camera that is fun to use and is capable of pretty nice images. I can’t say I enjoyed this any more or less than other box cameras of the era, but I am happy to have had the opportunity to shoot one and can easily recommend it to anyone looking to add one to their collection. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 30% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 7.8 | ||||||

Additional Resources

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Ensign_Ful-Vue

http://camerapedia.wikia.com/wiki/Ensign_Ful-Vue

http://www.ensign.demon.co.uk/ful-vue.htm

http://www.collection-appareils.fr/x/html/page_standard.php?id_appareil=66

https://kosmofoto.com/2016/12/11/zorkipedia-ensign-ful-vue/

https://thegashouse.wordpress.com/2016/11/21/ensign-ful-vue/