This is a Nikon F single lens reflex camera which was made by Nippon Kogaku in Japan from 1959 through 1973. It was Nippon Kogaku’s first attempt in the SLR market and was aimed at the professional photographer. The Nikon F both raised the bar for what a professional camera should be, but it also signaled a new era of Japanese dominance and innovation in the photography industry, a role that until this point had been played by Germany. The Nikon F lens mount is still used today on all Nikon digital and film SLRs, albeit with some revisions making it the oldest lens mount still in use. Nikon F cameras were popular during the Vietnam war for their toughness and excellent reliability, and have been used by photographers in countries all over the world, even in outer space. Many of the most famous photographers of the past 60 years have shot with a Nikon F camera at one time in their career. The Nikon F is one of, if not the most historically significant cameras ever made.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: Nikkor 50mm f/2.0 + others

Lens Mount: Nikon F Bayonet Mount

Viewfinder: Interchangeable Standard Prism + others

Shutter: Titanium Foil Focal Plane

Speeds: T, B, 1 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: none on camera, but were available in optional viewfinders

Battery: none on camera, but were required for metered viewfinders

Flash Mount: PC M/X-sync port plus optional hot shoe with Nikon BC-6 flash unit

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/nikon_pdf/nikon_f.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Nikon F is quite simply, one of the most important cameras ever made. It’s arrival signaled the end of German dominance in the camera industry and introduced the world to Japanese quality and precision. While the camera wasn’t the first to market with many of it’s features, it was built with a level of quality that had yet been seen by a Japanese camera. The Nikon F launched the entire F-series of SLRs which are still made today. If you’ve ever shot a film or digital SLR, some of that experience can be traced back to this camera. If you like a quirky camera with strange features and odd ergonomics, this is not the camera for you, but if you can appreciate a piece of history and want to use one of the best cameras ever made, there is none better. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 20% | |

| Bonus | +1 for historical significance, perhaps one of the most important cameras of all time. | ||||||

| Final Score | 15.4 | ||||||

Prologue

Released in 1959, the Nikon F was Nippon Kogaku’s (Nikon) first SLR camera and from the moment it was released, it changed the landscape of professional photography forever. It is one of the most important cameras in the history of photography as it offered many new and innovative features such as:

Interchangeable Bayonet Lens Mount(Actually, the Kine Exakta from 1936 had the first bayonet mount)Pentaprism Viewfinder(Nope, the Contax S from 1949 had the first pentaprism viewfinder)Interchangeable Viewfinders and Focus Screens(Foiled once again by the Exakta Varex from 1950)Instant Return Reflex Mirror(The Asahiflex IIb from 1954 had the first instant return mirror, but hey at least it’s a Japanese camera this time!)Automatic Diaphragm for Wide Open Composition(Stupid Zeiss and their Contax/Pentacon F from 1956)- Titanium Foil Focal Plane Shutter (HEY! We got one!)

Okay, sarcasm aside, the Nikon F wasn’t successful because it offered many firsts. Many of it’s features were already available by various competitors before it’s release, yet it stayed in production for over 14 years, and went on to become one the most highly regarded and historically significant cameras ever made. It cemented Nippon Kogaku’s stance in the camera industry as one of the greatest camera makers in the world, and officially signaled a new era of Japanese superiority in an industry once dominated by the Germans. So if the Nikon F didn’t have many new pioneering features, why was it so successful?

The answer was, quality. Every single feature on the Nikon F was built with the highest levels of quality and precision, achieving a level of reliability not yet seen in any Japanese camera up until this point. Nippon Kogaku took no shortcuts in the design and construction of the camera to ensure that they made the best camera possible. The Nikon F was durable enough to be used in outer space because of it’s dependability and resistance to vibration and high G-forces. It accompanied hikers to the heights of Mount Everest because of it’s resistance to extreme cold. It was favored by photographers shooting during the Vietnam war because it could withstand the humidity and heat from the jungle.

Today, modern digital cameras and smartphones require sealed bodies that offer water and moisture resistance, but the Nikon F didn’t need any extra sealing as it could handle the regular abuse and rigors of war just fine. The Nikon F was so reliable that it earned a reputation as a “hockey puck” because no matter what you did to it, it almost always kept working. In the rare event you did break a Nikon, it was usually something minor that could be easily fixed.

Another contribution to the Nikon’s success was the vast number of lenses, viewfinders, focusing screens, and other accessories available. The lens selection was massive. There was everything from 8mm fisheyes to 1000mm mirror lenses, and everything in between. Even though the idea of a modular “system” camera had existed prior to the Nikon F, Nippon Kogaku took this idea to the next level, and from the start had a dizzying array of products like motor winders, microscope attachments, bulk film backs, and many, many more.

The Nikon F checked off boxes on wishlists of professional photographers, even perhaps before those same professionals knew they wanted them. Combined with the build quality, excellent ergonomics, and huge number of lenses and accessories, the Nikon F would launch an entire series of professional F-series cameras that are still made today.

History Part One – The Meiji Restoration

Before we talk about the birth of the company that would eventually become Nikon, it is worthwhile to talk a bit about the history of industrialized Japan in the late 1800s. Much of what follows can be read in an excellent essay simply called “The History of Nippon Kogaku 1600 – 1949” by Hans Braakhuis which is available on Mr. Braakhuis’s website. It is an incredibly in depth history of the entire company, which I highly recommend reading if you are interested. I’ll try to summarize the relevant parts of their history to bring you up to speed.

I’ll start in the year 1868, which began a period known as the Meiji Restoration which coincided with the rule of Emperor Meiji, the 122th Emperor of Japan. The Meiji Restoration (or Renewal) was an event of change that began a new era for Japan that saw them become less of an isolated and private country. Although Japan had a long history with many emperors prior to Meiji, this period rapidly progressed Japan’s political, economical, and social status in the world. Emperor Meiji put an emphasis on education and industrialization which would allow Japan to be more self sufficient and less reliant on imported goods from other countries.

Throughout the 1870s, Japan began a period of military reform, transitioning from a reliance on the samurai and the Tokugawa Shogunate into a modern military comparable to those from Europe and the United States. The Empire of Japan would build a new military and would attempt to strengthen economic and military influence on the Pacific region. Eventually, Japan would engage in it’s first war, called the First Sino-Japanese War in 1894 and 1895. The Empire of Japan went up against the Qing Empire of China over interests in Korea. For the first 6 months of the war, it was mostly a stalemate, but Japan would eventually get an edge on China, eventually forcing their surrender in April 1895. For the first time ever, regional dominance in East Asia began to shift from China to Japan. It was a humiliating defeat for the Qing Empire, and would lead to an upheaval of power in China that would last decades.

Many of Japan’s naval boats and submarines during this time were purchased from European and American ship building companies. Military optics like binoculars and scopes were all made by Zeiss or other German companies. Emperor Meiji pushed Japanese industrial companies to develop their own homegrown boats and optics that would allow for Japan to be more self-sufficient.

The first test of an increasingly capable Japanese military came in the Russo-Japanese war of 1904 – 1905 when the Empire of Japan went to war with the Russian Empire over maritime ports in Korea and Manchuria, which is an area in north east China that was heavily influenced by the Russian Empire at the time. Russia’s biggest naval presence in the Pacific was in Vladivostok which was only open in the summer. Both Russia and Japan sought warm weather ports and went to war over them.

Once again, Japan’s military was too much for Russia, and the war was won with the Treaty of Portsmouth in September 1905. By this time, nationalism in Japan was at a fever pitch. Japan was now the most dominant military force in the East Pacific. Western nations in Europe and the United States were shocked not only that Japan had defeated the much larger Russian military, but had done so with such decisiveness.

History Part Two – Nippon Kogaku is Formed

After the Russo-Japanese war, the largest industrial manufacturing company in Japan was Mitsubishi Zaibatsu who became Japan’s primary shipbuilder. Japanese war ships were comparable to those purchased from British and American companies, however one area in which Japan was not able to compete in was optics. At the time, there was no Japanese optical company that was able to match the high quality standards of their German counterparts. As a result, a variety of small optics companies would open in Japan to attempt to duplicate the successes of the Germans.

Over the course of the next decade, many new companies would come and go, and the history of these small companies is poorly documented and confusing. As best as I can tell, there were three optics companies known as Iwaki Glass Seizo-sho, Tokyo Keiki Seisaku-sho, and Fuji Lens Seizo-sho who, in 1916, were asked by the Japanese military to design a new periscope for a new Mitsubishi submarine. Rather than work separately, on July 25, 1917, the three companies agreed to merge into a singular Japanese national optics company known as Nippon Kogaku Kogyo Kabushiki Kaisha, or Japan Optical Industries Co., Ltd. in English. This new company’s primary goal was to put an end, once and for all, on Japan’s reliance on imported lenses and rangefinders. The founding of Nippon Kogaku in 1917 came at the perfect time, as World War I had just broke out in Europe, and Japan lost it’s ability to get imported goods from Europe.

After the merger, the three factories that comprised the three original companies, continued to operate making specialized equipment for the Japanese Imperial Navy, the Japanese Army, and other scientific and industrial companies. Nippon Kogaku had over 200 employees, many of which had years of experience in producing lenses, microscopes, rangefinders, and other optical apparatuses.

Perhaps sensing a need for German expertise, in 1921, eight German engineers were hired by Nippon Kogaku with a contract to last no less than 5 years. Of the eight Germans, the two most significant were Heinrich Acht who was principal engineer of product design, and Professor Max Lange, who was in charge of optical lens design. Not much is known about where each of these eight German engineers might have been employed prior to coming to Japan, but the unemployment rate in Germany was very high after World War I, so it was likely not difficult to convince them to relocate to Japan and work for an otherwise unproven optics company. After the expiration of the original 5 year contract, Heinrich Acht would remain employed by Nippon Kogaku for another 3 years.

During their stay in Japan, the eight German engineers helped expand Nippon Kogaku’s product portfolio to include telescopes, binoculars, and aerial photographic lenses. Their first photographic lens was a direct copy of the 4-element Zeiss Tessar lens called the Anytar. The Anytar’s design was overseen almost exclusively by Heinrich Acht during his stay in Japan. After his departure, the Anytar continued to be refined, until eventually reaching or even exceeding the quality of the original. The Anytar lens was only made in pre-production form and never sold to the public. The only known copies are in the Nikon Museum in Japan.

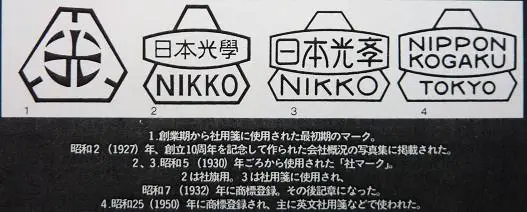

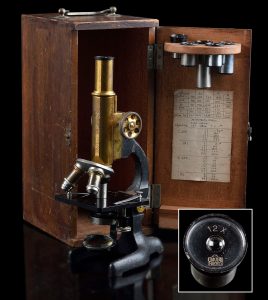

Although Nippon Kogaku was rapidly becoming a world leader in optics manufacturing, they hadn’t yet jumped into the world of camera making yet, instead focusing on microscopes and other devices. The earliest products made by Nippon Kogaku were labeled with the name ‘JOICO’ which is an abbreviation for Japan Optical Industry Co., which is a literal translation for Nippon Kogaku K. K.

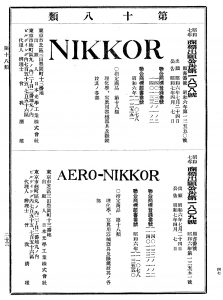

By 1930, the trademark “Nikko” would start to appear on microscopes, and in 1932, the name “Nikkor” was selected for the company’s lenses. To the right is a trademark application for the names “Nikkor” and “Aero-Nikkor” dated July 24, 1931. These trademarks were published on April 7, 1932 officially allowing Nippon Kogaku to use the Nikkor name for the first time.

History Part Three – Nikon and Canon Working Together

Ironically, Nippon Kogaku’s first foray into consumer camera design was while working in cooperation with another Japanese company called Seiki Kogaku, or Precision Optics Company in English, who would later become Nikon’s biggest rival, Canon. In those days, Japanese industry worked for the benefit of the Empire, so competing companies would often partner together to accomplish a task with greater expertise and efficiency than a single company might have been capable of.

Seiki Kogaku was founded in 1933 by a modest repair technician named Goro Yoshida, Yoshida’s brother-in-law Saburo Uchida, and a third man named Takeo Maeda with a goal of building Japan’s first compact 35mm camera. Their first prototype was called the Kwanon, named after the Buddhist Goddess of Mercy. It was heavily inspired by the Leitz Leica II rangefinder.

The Kwanon was shown in wooden and illustration form in various Japanese publications at the time, but according to Canon Global’s company history page, none were known to actually have been built. Goro Yoshida had at one time claimed to have built 10 Kwanon models, but this information has been doubted as none have ever been seen. There is at least one camera called a Kwanon Model D that is often cited as a real Kwanon, but it was later found to be a rebadged Leica II that was not actually built by Seiki Kogaku. Most online sources with information about the Kwanon camera, show this fake Kwanon Model D.

Although Seiki Kogaku had the necessary technology and expertise to design the body and shutter to German specifications, they lacked the expertise in optics design, something Nippon Kogaku was great at. As a result, the two companies worked together to release the first Japanese built 35mm rangefinder, and it came with a Nippon Kogaku lens.

The Kwanon was never sold to the public, and by the time it was ready for civilian consumption in 1936, it’s name had changed to the Hansa (or Standard) Canon. In manufacturing the Hansa Canon, Seiki Kogaku was responsible for the main body including the focal-plane-shutter, the rangefinder cover, and the assembly of the camera body, and Nippon Kogaku was responsible for the lens, the lens mount, the optical system of the viewfinder and rangefinder mechanism.

Seiki Kogaku would exclusively use Nippon Kogaku lenses until 1939, when they would finally start to produce their own designs. The first was the Seiki Serenar 50mm f/1.5. Although the outbreak of World War II would stall further developments, it is commonly believed that Nippon Kogaku would still maintain it’s lens making partnership with Seiki Kogaku until at least 1947.

Prior to the war, Nippon Kogaku was first and foremost an optics company, not a camera company. This did not stop them from working with other Japanese companies on specialized military camera designs that were used by the Japanese Navy and Air Force. None of these designs were ever sold to the public, and very little is known about them.

During World War II, Nippon Kogaku played an instrumental role in the design and development of aerial lenses and cameras. New models such as the Army Aero Camera Mark 1 were produced as late as 1944 during the later parts of the war. Aero-Nikkors were the most commonly used aerial lenses with focal lengths as long as 50 cm. An article published by the Nikon Historical Society in 2001 says that in 1945, at the end of the war, a factory in Ohi was filled with completed 2000 mm Aerial-Nikkors that were ready for the army, but never used.

History Part Four – Nippon Kogaku After the War

After Japan’s surrender in August 1945, American forces would shut down most of Nippon Kogaku’s factories. Some sources say that there were anywhere between 19 and 26 factories in total. Regardless of the number, during the period of American occupation in Japan, all military and weapons related manufacturing was prohibited. Nearly all of Nippon Kogaku’s work force became unemployed and the factories sat idle while the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP) examined future potential for the company’s resources.

Up until this point, Nippon Kogaku exclusively produced products for the Japanese military. With the sole exception of it’s partnership making lenses for the Hansa Canon, Nippon Kogaku had absolutely no experience producing and marketing designs for the civilian market. Despite this lack of experience, in the days after Japan’s surrender, the company’s many skilled workers were asked to come up with a list of viable products the company could make and sell.

The first product to resume production was a line of quality binoculars that Nippon Kogaku had made during the war. These binoculars were superior to other designs used by the American military, and upon capture of Japanese war ships, became highly sought after trophies for soldiers. Nippon Kogaku’s binoculars were seen as world class products, so it made sense to resume production on a commercialized version of these binoculars.

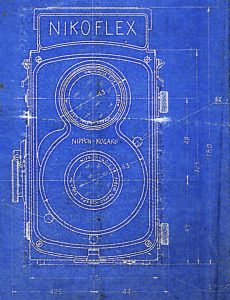

In total, a list of 38 products were selected as viable designs that could be made and sold. A variety of camera lenses, binoculars, telescopes, microscopes, spectrographs, and even cameras would soon roll out of Nippon Kogaku factories. In April 1946, Nippon Kogaku announced the development of two new camera designs, the first was an 80mm Twin Lens Reflex camera called the Nikoflex that was said to have an automatic film advance, a high quality leaf shutter, and Nippon Kogaku’s best Nikkor lenses. The best leaf shutters in the world were all made in Germany, which was also devastated after the war, so Nippon Kogaku set out to design their own leaf shutter, but it was decided quickly that such an undertaking would be prohibitively expensive. Only a few Nikoflex prototypes were ever built, and none are known to survive. Instead, the company decided to focus all of it’s efforts on a compact 35mm rangefinder with an interchangeable lens mount.

During the summer of 1946, Nippon Kogaku worked tirelessly on their new 35mm compact rangefinder. It went through several name changes, one of which was the Nikkorette, but in September 1946 when the first prototypes were produced, the name Nikon was chosen instead as a shortened version of the company’s name.

Not content to follow in the footsteps of Canon and design yet another Leica inspired rangefinder, Nippon Kogaku instead used both the Zeiss-Ikon Contax rangefinder and the Leica II as the basis for their new camera. It is said that Nippon Kogaku thought that neither the Contax or the Leica were perfect, and decided to take the best of both cameras and make their own. The new Nikon camera would share a lot of cosmetic similarities to the Contax, including the top focus wheel, removable film back, and a slightly modified bayonet lens mount instead of the Leica’s screw mount as it was faster to attach and detach, but also offered a more secure connection to the camera. From Leica, the Nikon would share it’s rangefinder and shutter designs. Rather than the vertically traveling “garage door” focal plane shutter of the Contax, the Leica’s horizontally traveling cloth shutter was chosen to both keep costs down and to reduce the overall height of the camera.

Although the initial design was completed in the fall of 1946, Nippon Kogaku would wait until March of 1948 to officially offer it for sale. Despite being very well built and innovative in design, the original Nikon (now known as the Nikon I by collectors) did not sell well. It is estimated that only 738 were ever made. The popular theory of the lack of success of this first model was the camera’s 24mm x 32mm exposure size, which was smaller than the 24mm x 36mm exposure made by most other 35mm cameras. It is said the head of SCAP, General MacArthur prohibited the export of the original Nikon as it would not be compatible with Kodachrome slides which were very popular at the time.

The original Nikon was sold for just over a year, and in late 1949, the Nikon M would be released which would increase the exposed image to a (still not standard) 24mm x 34mm frame. Despite this, the M sold a bit better than the original model. It wasn’t until the midst of the Korean War when American press photographers caught wind of a new Japanese camera that had superior optics and build quality to the German cameras often used until this point.

A story from the June 1951 issue of Modern Photography involves an American named Horace Bristol, who while visiting Tokyo in 1950 came across some 35mm negatives that he thought were sharper and more clearly defined than any he had seen before. He asked which camera made these negatives and was shown a Nikon rangefinder. Bristol was said to be so impressed with the quality of the camera that he bought one for himself. Shortly after, three Life Magazine photographers who had been covering the Korean War, met up with Bristol and saw his Nikon rangefinder. One of these photographers was famed war photographer David Douglas Duncan who was so impressed with the sharpness and detail in the Nikon slides, that he had a Nikkor lens adapted to his Leica and would primarily shoot with this combination throughout the rest of the war.

Upon reporting back to the Life home office about this new superior Japanese camera, the magazine ordered some cameras to be tested by optical experts who confirmed that both the cameras and lenses were of superior quality to anything made by anyone else. As a result, the Nikon rangefinder and it’s lenses became popular with all Life photographers and their reputation quickly spread throughout the United States and the rest of the world.

New features such as flash synchronization, larger viewfinders, a wind lever, and with the S2 from 1954, an exposed image size of 24 mm x 36 mm would soon be available. Despite these advancements, the Germans weren’t sitting idle either, and in 1954, Leitz would release the Leica M3 which was a brand new model designed from the ground up which helped to re-establish Leitz as the standard bearer for professional cameras. The Leica M3 improved upon the screw mount Leicas with some features that Nikon already had, such as a bayonet lens mount, adjustable frame lines in the viewfinder, a coincident image rangefinder, and a single dial shutter selector. The Leica M3 was seen as the pinnacle of rangefinder development up until this point.

Not willing to settle for second best, in 1955 Nippon Kogaku would start development on what would be called the Nikon SP, which was intended to be the culmination of Nippon Kogaku’s camera development. No expense was spared with this new model. The SP would have a parallax corrected viewfinder with frame lines for up to 6 different focal lengths. It would have an optional motor drive attachment that allowed up to a 3 frames per second shooting speed, making it the first rangefinder with such an option. Later SPs would have a horizontally traveling titanium curtain, improving upon the cloth curtains used by everyone else.

Upon it’s release in 1957, the Nikon SP bested the M3 in several areas, and proved that a Japanese company could meet and in some cases exceed the high quality and innovative standards dominated by the Germans. The SP was aimed at the professional photographer and had a price tag to go with it. Around 32,000 SPs were built, which is pretty spectacular considering the extremely high price of one. It has since been regarded one of the best rangefinder cameras of all time and is currently an extremely sought after model by collectors. In 2005, Nikon would re-release the SP as an anniversary model. 2500 were built and sold exclusively in Japan through a lottery system. The price was 690,000 yen, which was equivalent to nearly $8000 USD at the time.

History Part Five – The Nikon F SLR

Looking back on Nippon Kogaku’s success during this period, we can see that the company benefited greatly from their time making products for the Japanese military up to and during the war. They excelled in four key areas which allowed them to be highly successful in the post war camera industry.

- The first was that they had quite a bit of experience making prisms for periscopes and rangefinders. This knowledge in prisms would later give them an edge in the SLR market which had yet to develop at the end of the war.

- Second, they had a lot of innovative ways to apply lens coatings to lens elements to reduce flare and improve clarity on their designs. These lens coatings were necessary on the lenses used in underwater and aerial applications like submarines and airplanes. These coatings proved to be superior to those used by other manufacturers and helped cement Nikkor lenses as some of the best in the world.

- Third, Nippon Kogaku already had in place a large and well organized manufacturing and assembly process which allowed them to produce and make products faster, and with more reliability than other Western companies.

- Finally, Nippon Kogaku was no stranger to innovation and solving problems with new and creative solutions. Nippon Kogaku was regularly challenged by the Japanese military to create new products quickly and efficiently, and this creative process allowed them to change gears quickly in the civilian market coming up with new and interesting solutions.

Development of a Nikon SLR started in 1955 at the exact same time as the Nikon SP, but the SP had preference as the SLR market was still in it’s infancy at this time. Professional photographers preferred rangefinders as they were faster to shoot with than with an SLR. Many SLRs in the early 1950s still had waist level viewfinders which were dark and created a backwards image.

Shooting with an early SLR required many additional steps that were not necessary with a rangefinder. Before focusing, the user had to set the lens aperture to it’s maximum setting to brighten the viewfinder with a shallower depth of field. After focusing, the user had to manually adjust the lens aperture back to the desired setting. When the shutter was released, the mirror would remain in it’s up position, blocking out the viewfinder, preventing the photographer from tracking a moving subject and composing the next image. You’d need to advance the film to the next frame to lower the mirror and allow the viewfinder to be used again.

Each of these steps slowed the process down to a point where SLRs simply were not in demand by the same professionals that Nippon Kogaku was targeting with the SP. At first, development of Nikon’s first SLR was slow, but things quickly started to change. In 1954 the Asahi Optical Co would release the Asahiflex IIB which was the first Japanese SLR with an instant return mirror, and then in 1955, the Orion Camera Company would release the Miranda T which had a pentaprism viewfinder, and in 1957 the Asahi Pentax was released with both features, plus a microprism viewfinder, a film advance wind lever, and other conveniences that were not common to SLRs.

Suddenly, interest in SLRs had skyrocketed, and Nippon Kogaku put forth a lot more effort into the design of their as of yet unnamed SLR. Nippon Kogaku valued the input of professional photographers very much, and listened closely to their demands when designing their new SLR. They knew that it must have all of the modern conveniences offered by their competitors, but it must be done in way that had no compromises and maintained the high reputation that Nippon Kogaku had earned with their rangefinder series. The camera needed to exceed the expectations that a professional would have had for a camera.

Nippon Kogaku realized that with the release of the SP and the Leica M3, that rangefinder design was nearing the pinnacle of design and technology. They felt it was unlikely that there was much more that could be done to significantly improve the design, but that there was much more potential in the SLR market. Although Nippon Kogaku would later release an S3 and S4 rangefinder, these were both lesser models to the SP. The Nikon S4 would be released in 1958 and would be the last new rangefinder model to be sold. Nippon Kogaku did have two more rangefinders, known as the SP2 and SPX in development at the time, but they were never completed. Nippon Kogaku would discontinue any further rangefinder development, and focus entirely on their SLR line. This was a move not followed by any other camera maker at the time, as their competitors in Japan and Germany would continue to release new rangefinder models well into the 1970s.

Nippon Kogaku’s new SLR was designed using the body of the Nikon SP. It would share many of the same design characteristics, including most of the top plate controls like the shutter speed dial, advance lever, shutter release, and A/R knob for advancing and rewinding film. The two cameras would have a similar removable back, film pressure plate and the same PC flash sync. With the release of the Nikon SLR, both cameras would be upgraded with titanium foil shutter curtains.

To accommodate the necessary parts of an SLR, the camera body was widened to allow for a reflex mirror box to be included. One of the goals for an SLR was to have a viewfinder capable of 100% coverage, so a large opening was created in the top of the camera to allow for such a large viewfinder. One of the lessons learned from their conversations with professional photographers is that they wanted their camera to be used in as many shooting situations as possible, so an interchangeable viewfinder was added. This allowed for specialized viewfinders for macro photography, microscope attachments, astrophotography, and other specialized types of situations. In addition to the interchangeable viewfinder, the focusing screen would also be changeable to allow for ground glass, Fresnel screen, split image rangefinder, and microprism focusing aides. Nippon Kogaku put a lot of effort into making their new SLR be as flexible as possible.

Another feature of the SLR was a new bayonet lens mount. Although the Nikon rangefinder also had a bayonet mount, it’s internal diameter of 34mm was deemed too small to allow for future large aperture or heavy telephoto lenses. The Nikon SLR would have a larger bayonet mount with a 44mm internal diameter which would increase it’s strength, and would allow for a wider variety of standard and specialty lenses that Nippon Kogaku had planned. They wouldn’t have known it at the time, but their choice for this new lens mount was a good one, as it would be Nikon’s SLR mount for over 50 years, and is still in use today.

It’s worth noting that although the Nikon F-Mount is still in use today, there have been many slight revisions to accommodate for newer technologies like Automatic Indexing, Auto Focus, electronic aperture control, and vibration reduction. As a result, not every Nikon lens is compatible with every Nikon SLR body. Ken Rockwell has written one of the best Nikon lens mount guides I’ve seen, so I encourage you to check it out if you are interested in learning more.

Titanium was chosen as the material for the shutter curtains as it was both lighter and stronger than the coated cloth shutters used by everyone else, but it would also be immune to pinholes that could be burned into the shutter curtain if the photographer left the lens exposed to direct sunlight with the mirror up. The titanium used to make the curtains was only 0.02mm thick, but was very durable and strong. The use of titanium shutter curtains was not attempted by anyone else at this time, as there were many engineering challenges to both produce it, and to get the shutter timings right with such a light weight shutter. As a result, very early copies of the Nikon SLR were made with a cloth shutter. These cloth shutter cameras are very rare and highly sought after by collectors today.

Beyond all of the innovative features of the Nikon SLR, Nippon Kogaku valued reliability above all else. Every single component of the camera, from the shutter, to the winding mechanism, to the film transport system was engineered to the highest quality standards. Every part of the camera was subjected to extreme durability tests in hot and cold temperatures, vibration, and in the case of the shutter, was tested to allow for at least 100,000 shutter actuations. Nippon Kogaku made every effort to assure the Nikon F was beyond every other Japanese SLR in terms of fit, finish, and reliability.

While it was in development, the Nikon SLR was internally referred to as the “Nikon Reflex”, but according to Nikon’s official history of the Nikon F, the letter “F” was later chosen because the letter “R” is pronounced differently between English and non-English languages, whereas “F” is pronounced the same. The Wikipedia page for the Nikon F offers a different explanation that “F” was chosen in honor of a man named Mr. Masahiko Fuketa who was responsible for the design of the Nikon SLR.

Edit 9/1/2020: The topic of what the “F” in Nikon F stands for has come up a number of times, and despite the commonly held belief of that F was chosen because Japanese people can’t pronounce the letter “R”, I have personally heard from Nikon historian, Robert Rotoloni, who has heard from Fuketa himself, that “F” is for Fuketa. The camera was named after him in his honor, much like the original Olympus OM-1 (originally called the M-1) was named after it’s creator Yoshihisa Maitani.

I originally wrote this Nikon article in February 2017 before I had ever met Robert, so I leaned towards the “R” explanation. People are free to believe whatever version they want, but I’ll take Robert’s word over anything found on a website, even if it’s Nikon’s own history site.

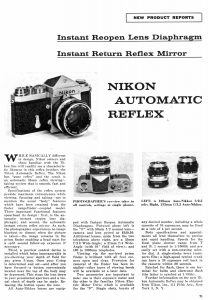

This Wikipedia page refers back to Nikon’s own history for this information, yet when you follow the link, there is no mention of a Mr. Fuketa anywhere in Nikon’s article. I don’t completely understand the explanation that “F” and “R” are pronounced differently, and the source for the Wikipedia explanation seems to be without merit, so who knows which one is right, but I guess it’s safer to accept Nikon’s own official explanation as fact. Interestingly, many advertisements and magazine articles of the era simply referred to Nippon Kogaku’s SLR as the “Nikon Automatic Reflex”.

The Nikon F spent nearly 4 years in development, and in March 1959, was finally announced in both Japan and the United States. Nippon Kogaku knew that in order for the camera to succeed, it must be successful in both domestic and export countries. The first appearance of the camera came at Japanese trade shows in April 1959, and to the United States in May. Roll out of the Nikon F was slow, but methodical. Nippon Kogaku wanted the camera to get a proper reveal in each city where the camera was announced to maximize it’s impact.

Upon it’s release, the Nikon sold with a standard pentaprism viewfinder and 50mm f/2 Nikkor lens for 67,000 yen in Japan and $329.50 in the US. When adjusted for inflation, that’s nearly $2780 today. Despite the high price, the Nikon F saw immediate success and generated a lot of positive feedback. In a Japanese trade show in March 1960, Nikon’s booth was one of the busiest in the whole show. At Photokina in September 1960, the camera continued to garner tremendous praise and quickly became the de-facto standard for professional photographers.

It seemed that Nippon Kogaku’s experience making products for the Japanese military for all of those years and their extreme dedication to quality and innovation paid off because for the first time ever, not only had a Japanese company exceeded any comparable product made anywhere else, but they also established Japan as a force in the manufacturing sector. No longer would the label “Made in Japan” be seen as a bad thing. Japanese companies like Sony, Mitsubishi, Hitachi, Panasonic (Matsushita), Toyota, Honda, Nissan, Nintendo, Yamaha, and many others would lead their respective industries and release countless products and services that we use regularly today.

Here is a gallery of some magazine ads from around the time of the Nikon F’s release showing how it was advertised in the marketplace.

In the years after the Nikon F’s release, it would become the preferred camera system for photographers all over the world. Their reliability, flexibility, and quality were never exceeded by anyone else. Even today, original Nikon F cameras are highly desirable by collectors and film students as they not only offer a glimpse into the photographic past, but they still perform quite well. Even if you manage to find one in a non-working state, there are still dedicated shops that will service and repair it for you.

The Nikon F would eventually be superseded by the F2 in 1971 and production would end in 1973. In total, over 800,000 Nikon F’s were made which is significant as it was mostly purchased by professionals and not sold as a point and shoot family camera. It launched a whole F-series of cameras that ran through the F6 which as of 2017, is still sold new from Nikon. The Nikon F was not just a historically significant camera, it’s release represented a historically significant event that changed an entire country, which in turn changed the world and everyone in it. Sure, there were other cameras and other industries that saw success after the Nikon F, but it’s impact on the world’s economy is still felt to this day.

My Thoughts

I am writing a review for the Nikon F…

Just let that sink in for a moment. The Nikon F is without a doubt the most historically significant camera in my collection and perhaps the most significant in the history of photography. It represented not only a permanent shift in the market from rangefinder cameras to SLRs, but it also put the final nail in the coffin of German dominance in the photographic industry. Of course, neither rangefinders nor German companies rolled over and died the moment the Nikon F was released, but it was the turning point which established one country’s prowess in an industry that was once dominated by another. It represented a total change on how we used cameras and how photography was done.

Most of you reading this already know the Nikon F was a great camera. Even if you aren’t a “Nikon guy” or even if you have never shot a film camera in your life, you are likely at least familiar with Nikon’s professional line of film and digital cameras which started with the Nikon F. Sure, Nikon (Nippon Kogaku then) had been making pretty good rangefinders prior to 1959, and there is more than just a passing similarity between that original Nikon F and the Nikon S3/SP/S4 rangefinder, but Nikon’s history can be identified as one of two eras, before the F and after the F.

Regular readers of my site will know that I rarely go for expensive cameras, and I also have a hard time writing about Nikon cameras. I talk about this a bit in my Three Decades of Nikon’s super-review where I review the Nikomat ELW, Nikon N2020, and Nikon N90s. I say that being a fan of the system makes it difficult to really come up with anything worth saying about a camera I am so fond of.

This Nikon F is actually the second one I have acquired, the first having a broken shutter that I tried unsuccessfully to repair. The one being reviewed came to me from a Japanese seller who fairly listed it as having inoperable slow speeds, a dent in the prism and a dirty body. This camera whose serial number dates it to 1966 shows heavy signs of use. How much use exactly? I’ll never know, but I am absolutely certain this camera has seen some interesting stuff in it’s 51 years on this planet.

I’ll save you any more editorializing and just get straight to the point. What is it like to use a Nikon F? Considering this camera changed very little since it’s original release in 1959, using my particular example is essentially the same as what someone might have experienced back when it was first released. How does an SLR from 1959 compare to those from decades later?

In a word, excellent.

When I use older cameras from the 50s and 60s, I generally try to change my expectations of those cameras as the technology wasn’t what it was in later years. I am going to expect an older camera like a Minolta SRT-101 from the late 60s to have a dimmer viewfinder than that of a Minolta X-570 from the 80s. I am going to expect a smaller, and harder to use focusing system in a early rangefinder than that of a more advanced SLR. Knowing that the Nikon F was developed in the 1950s, I was prepared to be underwhelmed with the camera, but that turned out to be far from the truth.

In fact, I would say that the Nikon F in some ways compares more favorably than some SLRs that came years, or even decades after it. Compared to electronic auto exposure cameras of the 70s and 80s, this is a rudimentary camera for sure, but it performs all of it’s functions with extreme precision and perfect execution. All of the controls are positioned and work exactly where and how you’d expect them to. The balance of the body is perfect. The viewfinder is bright and easy to use. The image to the right of the viewfinder shows an evenly bright and easy to use TTL image. I know the Nikon F had interchangeable focus screens, but I was elated to find that my example had a split image focus aide, something that was not consistently available until the mid 1970s by other companies. There is a certain reassurance to the shutter’s sound, the lack of any sort of electronics, and the general feel of the camera.

The top plate of the camera borrows some elements from the Nikon rangefinder like the wind lever, exposure counter, shutter release, and shutter speed selector. It’s not obvious by looking at it, but the two vertical contact points to the left and right of the rewind knob are flash sync points for an accessory hot shoe which clips onto the camera and sits above the rewind lever.

The bottom plate of the camera shows the single release for the film back, and tripod socket, and ASA speed reminder dial. While the removable back of the camera makes changing film out in field slightly more difficult, at least there’s only one lock to deal with.

Nikon can’t really take credit for too many firsts with the Nikon F as many of it’s best features were available prior to 1959, but what Nikon did was combine everything that was great about SLRs into one single camera, harmoniously designed with the highest level of quality. The Nikon F was to SLRs what the Leica M3 was to 35mm rangefinders and what the Rolleiflex was to the TLR. I wonder what people’s reactions would have been in 1959 if you were to tell them that this new camera would set the standard for SLRs for the next 60 years and more.

The only real complaint I can give the camera is the standard one that almost everyone mentions, which is the removable film back. While an acceptable way to load film in the 1950s, the hinged back quickly became the preferred design, and one Nikon would be sure to update with the release with the F2, it’s just a shame it took them 13 years to replace the removable back.

Beyond the back, if I had to come up with one more nitpick it’s that the camera is so well designed, and so typical of cameras from the next few decades, the experience can be somewhat forgettable. Some of my favorite reviews for this site are for cameras like the Ihagee Exakta or the Univex Mercury CC that have strange ergonomics or characteristics that make them fun and memorable to use. The Nikon F has none of that. If you were to give this camera to someone who didn’t know what it was, when it was made, or it’s history and asked them to date it, I would be willing to bet they would place this camera as being made in the mid 70s or later. Nikon hit a home run on their first try, and people have been copying them ever since.

I was pleased to get a Nikon F with the standard prism as the Photomic ones that are often paired with early Fs are quite ungainly looking. I am a big fan of symmetry and the off center design of the metered prisms look out of place and give the camera a top heavy appearance. Also considering the meters in many of these early prisms are usually dead, I was especially happy to have the standard prism and not have to see a motionless needle in the viewfinder every time I peered through it. The only down side to the standard prism is that they’re a bit more desirable these days, so ones with the prism included will often raise the selling price of the camera a bit.

My Results

Setting aside the reputation of the Nikon F, shooting one isn’t a whole lot different than any other Nikon ever made. All of the controls are exactly where you expect them to be and with few exceptions, the camera can mount any Nikon lens made ever since.

The Nikon F is a professional camera, it’s strengths and weaknesses are limited by the person behind the lens, not the camera itself. Simply pointing a Nikon F with a Nikkor 50/1.8 lens at something and capturing a photo will give you the same exact image as if you had used the same lens on a Nikon EM.

So, while I’m happy to share some sample images I got with mine, they’re not likely to look much different than those shot with other Nikons in my collection. While I’d like to think I do a pretty decent job with these reviews, I am far from a skilled photographer. The images below are what I got using my Nikon F, a lens, pointing it at something, and pressing the shutter release.

Although all of the “beauty” images of the Nikon F in this review show it with a Nikkor 50/2 lens mounted, I shot my first roll using a Nikkor 50/1.4 lens. I used the 50/2 lens as I think it photographs better.

When I got my film back from the lab, I expected the images to look great, and they did. Normally at this point in a review, I would comment on how sharp the image is and if it softens near the edges. I would say if I saw any vignetting, chromatic aberrations, or other lens anomalies, none of which are here.

For as long as this review is, I really don’t have anything to say about the images I got, because they are technically perfect.

Many of the images in the gallery above were from the Chicago Auto Show which is famous for millions of combinations of fluorescent lighting, super bright LEDs, neon bulbs, reflections, shadows, etc. The indoor shots were taken mostly between f/2.8 and f/5.6 at 1/125. For the outdoor pictures, I used Sunny 16 and shot at f/11 (or something close). The above 12 shots are just a sampling of the roll, but I could have shown you more and they would have all looked just as good.

I have no critique, or thoughts on the images themselves, because what could I really say? If anything, the fact that I keep rambling on about not saying anything, says something. It says the Nikon F is absolutely deserving of the praise, adulation, admiration, and imitation it’s received in the 6 decades since it first went on sale. It does not matter whether you have a Nikon F made in 1959, or in 1973 as they are all good. Quite simply, the Nikon F is more than just a camera, it’s a piece of human achievement and absolutely belongs in any collection.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://imaging.nikon.com/history/chronicle/history-f/

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Nikon_F

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nikon_F

https://www.cameraquest.com/fhistory.htm

https://www.bhphotovideo.com/explora/photography/hands-review/classic-cameras-field-mighty-nikon-f

http://www.mir.com.my/rb/photography/hardwares/classics/michaeliu/cameras/nikonf/index.htm

https://www.casualphotophile.com/2014/08/27/nikon-f-camera-review/

That was a very interesting and edifying review. I thought I knew a bit about Nikon history, but I learned a lot more today. I imagine you put quite a bit of time into your reviews. Thanks again.

Great, beautiful article! I can try to clarify one part: The “F” letter has been chosen because it has a phonetically international pronunciation while in asian countries and others, the letter “R” can be, or actually are, pronounced as the letter “L”. So if you want to say “Live Music” in japanese e.g it would be “Raibu Myujiku”. In other words choosing the letter “F” was a good choice for International marketing reasons.

Very comprehensive review and article… thanks a lot

Sorry for the late comment. I’m interested in the statement “There is at least one camera called a Kwanon Model D that is often cited as a real Kwanon, but it was later found to be a rebadged Leica II…” Can you point out the source of this finding? I’m assuming this refers to the camera sold at auction in Boston in July 2006 (http://www.klassik-cameras.de/Kwanon_RF.html) but I haven’t been able to find aa record of when or how it was debunked. Thanks for any info!

JL, I apologize but I cannot find the reference I used when I typed that up, but it’s been over a year and a half since typing that part of the Nikon F review, I can’t find it anymore. I typically don’t state something in my reviews if the source did not at least appear to be credible. Sadly, when researching old cameras, sometimes you have to take a leap of faith.

Since that review though, I have learned a lot more about Canon and Nikon’s early days and have acquired a book written by Peter Dechert, called “Canon Rangefinder Cameras 1933-68” in which he says he has personally seen a Kwanon-X in Canon’s Tokyo museum. The link you provided to an auction where a Kwanon-D was sold seems pretty convincing as well. It would seem that section of the Nikon review where I claim the Kwanon-D to be a disgused Leica is not correct. When I get around to it, I will attempt to dig up more information and correct this review.

Thank you for challenging me on this. I don’t always get it right, but I’ll always fix something if it’s wrong!

Hello, Mike, thanks for the follow-up! I’ll keep looking around for more information about Kwanon-D.

I have to say that based on looking at the pictures from the auction, if it IS a forgery, the guy who forged it was a master craftsman! It would have had to be built by hand, from scratch, the same way Goro Yoshida supposedly built the original Kwanons. (What little I’ve been able to find out about Yoshida says he was “just” a motion-picture equipment repairman… but back in the ’30s a lot of that equipment wasn’t standardized, and to fix it you had to be really good at fabricating parts!) Interesting to try to imagine what it was really like for the pioneers back in the ’30s… we’ll probably never know all of what went on!

Thanks again for an honest response and an enjoyable site!