This is a Minolta Auto Wide 35mm camera made by Chiyoda Kogaku Seiko K.K. in 1958. It was a scale focus camera that had a unique combination of a wide angle lens, a coupled selenium exposure meter, and a unique click stop focus system to simplify focus and exposure for the growing novice photographer of the time. Despite it’s aim for a simpler feature set, the Auto Wide was a very well built, solid metal camera that had an excellent 6-element Rokkor lens, allowing the camera to produce extremely detailed and sharp photographs. The Auto Wide was only in production for a year or two, giving way to less expensive, and simpler auto exposure cameras.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 35mm f/2.8 Minolta Rokkor coated 6-elements

Focus: 2.6 feet to Infinity with Click Stops for Portrait, Group, and Scenery

Viewfinder: Scale Focus with 35mm Projected Brightlines

Shutter: Optiper MXV Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: Coupled Selenium Cell w/ top plate match needle

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Coldshoe and M and X Flash Sync

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/minolta_pdf/minolta_autowide.pdf

History

The 1950s was an extremely active time for innovation in the camera industry. In that decade, the Japanese camera market went from a distant second place, to a world wide leader. The rangefinder camera lost it’s stance to the SLR as the preferred style of camera for professionals. Companies like Nippon Kogaku (Nikon), Canon, Konishiroku (Konica), and Chiyoda Kogaku (Minolta) went from second and third tier companies making knock offs of German designs to industry leaders making high quality and innovative cameras. Also, the selenium cell exposure meter gave novice photographers a reliable, and in some cases automatic, method for calculating exposure.

In 1958 specifically, a huge number of new cameras from pretty much every single Japanese company flooded the market with new and unique features. I have reviewed more cameras on this site introduced in 1958, than any other single year in history. What was state of the art in 1957 was “old school” by 1959. Although this was 20 years before I was born, I have to imagine this was an exciting (and probably very confusing time) to be a consumer in the photographic market.

As with any industry that is in a transition period introducing new technologies, some designs worked really well, and some, not so much. The Minolta Auto Wide was a curious camera that had features aimed at the beginner photographer, but was still well built and came with an excellent 6-element Rokkor lens, a fully flash synchronized 9-speed shutter, a self timer, and a coupled selenium cell exposure meter.

Minolta marketed the Auto Wide as having the world’s first automatic exposure system. This was a bit misleading however, as the Auto Wide doesn’t actually do anything automatically. Where the term “auto” comes from is that the camera’s meter is coupled to the shutter speed and aperture selector and it will automatically reflect a light value dependent with the chosen shutter speed and aperture size. Sadly, the Auto Wide wasn’t even the first camera with this feature, that honor goes to the also short-lived Mamiya Elca which was introduced mere weeks before the Auto Wide.

Unlike most “match needle” cameras of the 60s and 70s, the needle was only visible on the top plate of the camera and not in the viewfinder. Also unlike most other cameras, the shutter speed and aperture selector were controlled by a unique dual “exposure setting dial” on the back plate of the camera. The exposure setting dial worked like a typical Light Value Scale (LVS) found on many 50s and 60s cameras. The wheel has both an outer ring and an inner ring. Turning the outer ring adjusts both shutter speed and aperture to maintain a consistent light value, but when pressing and turning the inner wheel, the shutter and aperture numbers can be changed individually.

I mentioned earlier that many cameras of this era had unique designs as each company had to figure out the best way to implement new technologies and this rear exposure setting dial was likely one example of pioneering experimentation. Perhaps the reason for the design of this wheel was to keep the exposure controls as close to the meter as possible. Perhaps Chiyoda was not confident in their ability to couple the meter to the shutter speed and aperture selectors if they were on the lens.

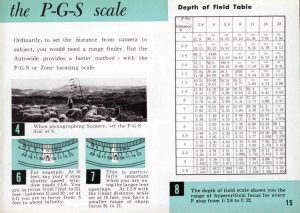

Beyond the innovative exposure system, the Auto Wide’s other feature that was likely done in an effort to simplify it’s use was the focus wheel on the lens. The 35mm Rokkor lens has markings to select a focus distance from 2.6 feet all the way to infinity, but it also has click stops marked P, G, and S for “Portrait”, “Group”, and “Scenery”. Each of these click stops is at approximately 3.5, 8, and 16 feet. Although not advertised as such, each of the three click stops are ideal zone focus spots to maximize depth of field at apertures of f/5.6 and up.

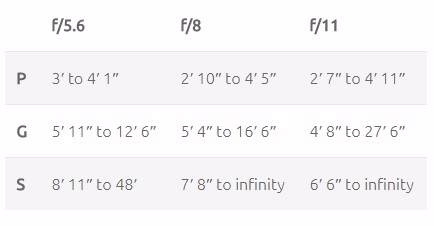

The 35mm lens on the Auto Wide is a very shallow “pancake” style lens that keeps the size of the camera down. It’s focal length was chosen to maximize depth of field to simplify focus estimation, as the wider the lens, the more depth of field you have. Using the chart to the right from the Auto Wide’s user manual, at 10 feet away and an aperture of f/8, you get a depth of field of approximately 6 ft to 28.5 feet. Had this camera came with a 50mm lens, with everything else the same, your depth of field would be reduced to approximately 8 feet to 14 feet. Although not exactly an industry secret, maximizing depth of field in a fixed lens camera wasn’t done by many companies. Aside from the Auto Wide, a few models by Olympus, Ricoh, and Yashica did it, but none of these were very common.

I could not find much information about sales figures for the Auto Wide, but it must have been pretty low as the camera was only in production for about a year. It’s list price of $89.50 is comparable to to $758 today, so it wasn’t exactly cheap either. I would hesitate to call it a failure however, as the camera does have some compelling features that would have made it appealing at the time. I think it’s short life cycle was more a result of the extremely fast pace of new advancements in the late 1950s. Cameras with true auto exposure and coupled match needle systems visible in the viewfinder would be released shortly after, making the Auto Wide seem outdated in a very short period of time.

Today, there is little to no talk about this model. I doubt many collectors even know it existed. The late 1950s and early 1960s was such a transitional time in photography, that many models came and went almost over night. Despite it’s lack of notoriety, the Minolta Auto Wide is a well built camera with an excellent lens and curious controls, from a innovative period in camera development. It’s worth picking up if one ever were to cross your path.

My Thoughts

I first learned of the existence of the Auto Wide on Mike Connealy’s photo review site, which I currently mirror. I was immediately drawn to the compact size of the camera, it’s unique control layout, and the promise of a wide angle lens on a fixed lens camera. I don’t think I realized at first that this camera didn’t even have a rangefinder, but I wanted one anyway. It would take me over a year to find one in good enough condition and in the price range I am comfortable spending.

When it arrived, I was pleased to see the camera was in good working condition and other than a general wipe down, needed no additional help from me. The Auto Wide predates the use of foam light seals, so there was nothing in the way of repairs that this camera needed. Just clean off the 5+ decades of grime, load in some film, and start shooting.

The strange rear mounted LVS knob for changing shutter speeds and aperture sizes has one immediate benefit which is that the lens is extremely shallow. If you didn’t know better, you might guess that this camera has a collapsible lens that must be extracted before the camera can be used, but that is not the case. The 6-element Rokkor sits almost entirely within the body of the camera with only the focus ring and front elements protruding out of the front.

The small and compact lens is somewhat negated by a relatively large body. The Auto Wide, like most 1950s rangefinders isn’t exactly small. It would not fit in the average shirt or jeans pocket. The camera predates the prevalent use of plastic, so almost everything is metal, giving the camera a bit of heft. Weighing in at 717 grams, the Auto Wide has just enough weight to inspire confidence, without feeling unnecessarily bulky.

Loading film into the camera is pretty uneventful. The film compartment door is hinged on the right and employs a sliding latch on the left side of the camera, like most cameras of the period. The bottom of the supply side has a curved recess that allows easy installation of a new cassette. This is necessary since there is no way to pull up on the fork like on more contemporary 35mm cameras.

Once the new cassette is installed, the leader is attached to a single slit in the take up spool. A notch near the bottom of the slit helps hold the film leader in place. Wind the camera twice to make sure the film is traveling to the take up spool correctly, and then close the door.

The Auto Wide is a bottom winder. To my knowledge, its the only Minolta camera that winds from the bottom, like many of the 1950s Kodak Retinas did. This was most likely done to make room for the exposure meter and it’s rear LVS wheel up top.

Also on the bottom of the camera is the film rewind knob which must be activated by first pressing a small release button next to the tripod socket. In the image to the left, you can see the inconspicuous release button between the tripod socket and the wind lever. Pressing this button also puts the camera in “rewind mode”, disconnecting the film transport.

In the image to the right, you see the rewind lever in it’s “out” position. You can also see a small “X” shaped shaft with a red line on it which is connected to the film cassette fork. This red line is what you use to confirm film transport. As you advance the film, the line should rotate. If it is not rotating, then either you have excessive slack in your film cassette, or the film leader is not properly attached to the take up spool. When you are done rewinding the film, you press the rewind lever into the recess.

Minolta’s decision to move both the wind and rewind levers to the bottom of the camera leaves quite a bit of room for the match needle exposure system on top of the camera. From left to right is the automatically resetting frame counter, cold shoe, shutter speed and aperture size indicator, threaded cable release socket, and then the exposure meter.

One of my less than favorite cosmetic elements of the Auto Wide is that the selenium meter looks like it was grafted onto the front of the camera as an afterthought. At a glance, the meter looks like one of those optional clip on meters that was common in the early 60s on cameras like the Minolta SR-1. Additionally, the shutter release is integrated into the top plate of the meter, and not on the camera itself. Thankfully, it’s location is in easy reach of your right index finger. It doesn’t look elegant, but it does work well.

To use the exposure system, you must first set the proper film speed by pressing down on the chrome wheel in the center of the meter and turning it. The meter supports film speeds from ASA 10 to 1600.

Once the correct film speed is selected, a red arrow on the inner dial points to an unmarked exposure value. This red arrow is coupled to the exposure selection wheel on the back of the camera. As you turn the outer ring of the exposure wheel, this red arrow will move. Also visible in the exposure window is a white needle that is connected to the meter. As the meter detects light, this needle will move. The idea is to “match” the red arrow to whatever exposure setting the white needle is pointing to. Although nowhere near as elegant as later match needle systems visible within the viewfinder, you quickly get used to how it works. If my description doesn’t make a lot of sense, trust me, within 30 seconds of holding the camera, you’ll figure it out.

What’s not quite as intuitive is independently changing the shutter speeds and aperture values. To do this you use the inner dial on the exposure selection wheel. Normally the two values are coupled together, but if you need to override the selection, this wheel will do that for you. I found that while using the camera, trying to rotate the inner wheel would often turn the outer wheel too. This would require me to hold the outer dial steady with one finger, while turning the inner dial to get a specific shutter speed and aperture combination. I mention earlier in this article how this period of camera design was often filled with curious design choices, and this is definitely one of them. As much as I appreciate quirky things on old cameras, this aspect of the Auto Wide does wear your patience thin while shooting. If you are outdoors shooting the camera in consistent lighting, you don’t have to mess with these settings much, but if you often go between full shade and bright sunlight, you’ll find yourself fumbling with this control often.

Thankfully, the rest the Auto Wide experience is pleasant. I quite liked the P-G-S focus system. Designed to maximize the increased depth of field of a wide angle lens like the Rokkor 35mm, the three positions are good enough for most outdoor photography. As long as you are using an aperture of f/5.6 or higher (f/8 and f/11 are even better) you can reasonably switch between these three settings without ever having to look at the actual distance scale on the side of the lens. The Auto Wide does not have a rangefinder because it doesn’t need one. In fact, I’d argue that an easy to use zone focus system like this is actually faster than a rangefinder because it frees you up from having to sit there and analyze your distances. Just get the camera to the correct click stop and shoot. The click stops are pronounced enough that you can easily “feel” them with the camera to your eye.

The table to the right shows the depth of field range for P, G, and S at apertures from f/5.6 – f/11. As you can see, when using the Auto Wide in good lighting, you don’t need to spend much time thinking about focus. Unless you move into full shade, or shoot something really close, you can safely keep the camera at f/8 or f/11 and at G or S for almost any scene. The best part about the P-G-S system is that if you want to measure your focus precisely, you can simply ignore them. The camera can be manually set to any focal distance from it’s minimum setting of 2.6′ to infinity. There is also a small depth of field chart on the side of the lens, beneath the meter.

The table to the right shows the depth of field range for P, G, and S at apertures from f/5.6 – f/11. As you can see, when using the Auto Wide in good lighting, you don’t need to spend much time thinking about focus. Unless you move into full shade, or shoot something really close, you can safely keep the camera at f/8 or f/11 and at G or S for almost any scene. The best part about the P-G-S system is that if you want to measure your focus precisely, you can simply ignore them. The camera can be manually set to any focal distance from it’s minimum setting of 2.6′ to infinity. There is also a small depth of field chart on the side of the lens, beneath the meter.

Looking through the viewfinder is a very pleasant experience. Since there is no rangefinder, there is no need for a partially reflective beamsplitter like on most late 50s and early 60s cameras. Beamsplitters by their very design need to reflect a portion of their light towards the second window, thus lowering the amount of light that reaches your eye. This results in a slightly darkened image that can make composition tricky in low light situations. The viewfinder in the Auto Wide is a straight through design that is large and bright. There are also projected frame lines representing the full 35mm frame. The frame lines are not parallax corrected, but there are tiny hash marks that help when focusing at the camera’s minimum distance.

The Minolta Auto Wide may not be as “automatic” as Minolta suggested, but it is still a quick and easy to use camera. When paired with Sunny 16 and consistent lighting, shooting the Auto Wide isn’t far off from a point and shoot camera. The unique exposure wheel on the back of the camera is a bit clunky, but as long as light isn’t always changing, you can mostly leave it alone.

Despite the proliferation of fixed and interchangeable lens cameras with 50mm lenses, I don’t particularly find that focal length to be ideal for candid shots. I prefer cameras like the Bolsey B2 at 44mm, the Canonet GIII QL17 at 40mm, and this Minolta Auto Wide at 35mm. Not only does it make getting accurate focus easier, it also allows you to capture candid moments like fast moving children, or group shots of people standing around.

This is a wonderful camera that was built at a time before cost saving plastic was common. It is made almost entirely out of metal and glass and as such has a heft that inspires confidence. Although the body isn’t quite as small as a 70s or 80s point and shoot, the low profile “pancake” lens makes carrying in a large pocket or small handbag very easy. I enjoyed my time with the Auto Wide and can positively say that as long as I don’t run into any kind of mechanical failure, this is a camera that will see repeated use in the future. It’s too bad that there weren’t many other fixed lens “wide angle” cameras like this.

My Results

For my first roll through the Auto Wide, I tried to put myself into the shoes of a typical customer who might have purchased this camera when it first went on sale. I shot almost the entire roll at a family function of children and fast moving subjects. I chose Fuji 200 film not only because that is often my default film but that its also a pretty basic and simple film, that generally gives good results in many shooting situations.

I was extremely pleased upon seeing the first scans of film from this camera. As promised, each of the images are typical “snapshots” that someone might have taken of their kids running around and playing in the yard.

As I expected, the 6-element Rokkor lens rendered the images nicely, with excellent sharpness across the entire frame. I saw no vignetting, or optical anomalies in any of the images. Like most of the premiere Japanese lens brands (Nikkor, Hexanon, F.Zuiko, etc), you can safely assume extremely sharp and nicely rendered images.

Out of the 24 total images from this first roll, there were 2 that I didn’t quite get the focus right on, but that’s still impressive the first time shooting any classic camera, let alone a scale focus one with no rangefinder or any other focus aide.

The Minolta Auto Wide may have been a short lived camera that is rarely on the radar of most collectors, but it’s a unique looking camera with some cool features that definitely deserves a look if you ever happen to find one. Perhaps a better name for this camera should have been the Minolta Simple Wide, as it’s features make things simpler for you, but not quite automatic. I’d have to say that the Auto Wide was the easiest scale focus camera I’ve ever used, and I am sure that with more practice, I should be able to consistently hit 100% correct focus. This is a really cool camera and I am glad to have found it.

My Final WordHow these ratings work |

The Minolta Auto Wide was a short lived compact scale focus camera that had a unique exposure system and three stop focus system that allowed the photographer to easily set focus in a way that works in most shooting situations. The presence of the word “auto” in it’s title is a bit misleading as the camera does nothing automatic, but it does simplify the act of measuring exposure and setting focus so that most people could use it without much training. Made of all metal and glass, the camera is built to typical 1950s standards, and equipped with an excellent 6-element Rokkor, your images should consistently come out sharp and without any optical anomalies. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 30% | |

| Bonus | +1 for a unique combination of features around a solid camera with excellent lens, not found in any other model | ||||||

| Final Score | 10.1 | ||||||

Additional Resources

http://camerapedia.wikia.com/wiki/Minolta_Autowide

https://mikeeckman.com/photovintage/vintagecameras/autowide/index.html

https://www.photo.net/discuss/threads/wide-and-wonderful-the-minolta-autowide.495818/

http://www.collection-appareils.fr/x/html/page_standard.php?id_appareil=11552

I have this Minolta camera as featured. I am not using this model anymore and wondering how much it is worth and where to sell it. Have flash also

Please advise thanks

Hi Mike. The Auto Wide certainly is a neat camera, but its not worth much. In untested condition, I think you’d get $20 maybe $30 for it. If you’re looking to donate it, you could send it to me and I’d fix it up and make sure it gets to a good home.

Wow. You really did your research.

These shots are a prime example of how film handles dappled light v digital .Nice review and you’d be happy with the shots?