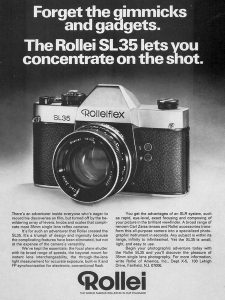

This is a Rolleiflex SL35 single lens reflex 35mm camera made by Franke & Heidecke of Braunschweig, Germany between the years 1970 and 1976. Earlier versions like this one were made in Germany, later ones in Singapore. The SL35 was the first 35mm SLR to bear the Rolleiflex name and introduced an all new QBM “Quick Bayonet Mount” unique to these cameras. Although this camera had extraordinary build quality and is often found with an excellent 7-element Zeiss Planar lens, it lacked open aperture metering, a feature that most other SLRs of the day had.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 50mm f/1.8 Zeiss Planar coated 7-elements

Lens Mount: Rollei QBM Bayonet

Focus: 18 inches to Infinity

Viewfinder: Fixed SLR Prism with Microprism focus aide

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: Twin CdS Cell w/ viewfinder match needle

Battery: PX625 1.35v Mercury

Flash Mount: PC-port with FP and X Flash Sync

Weight: 594 grams (body only) / 779 grams (w/ Planar lens)

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/rolleiflex/rolleiflex_sl35.pdf

My Final WordHow these ratings work |

The Rolleiflex SL35 is a late entry into the 35mm SLR market by a company who didn’t have a lot of experience with 35mm SLRs. This camera is heavily inspired by the Pentax Spotmatic and has Japanese style, but with German levels of quality. There are many subtle improvements that this camera has which aren’t immediately obvious when first looking at it, but that comes at the expense of modern (for the time) features, which was a disappointment. Putting aside the things it doesn’t have, what the SL35 does well, it does REALLY well and for that, it’s a worthy addition to any collection. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 20% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 9.6 | ||||||

The name “Rolleiflex” or simply “Rollei” refers to a brand of cameras produced by a company called Werkstatt für Feinmechanik und Optik, Franke & Heidecke (or Franke & Heidecke for short). The company was originally founded in 1920 by two former Voigtländer employees, Paul Franke and Reinhold Heidecke in Braunschweig, Germany.

Their first products were a line of plate film and roll film stereo cameras called the Heidoscop and later the Rolleidoscop. These cameras all had a similar form factor of twin “taking” lenses and a third viewfinder lens in the middle. All three lenses were arranged horizontally and generally used Zeiss lenses and Compur shutters.

Franke & Heidecke’s stereo cameras were a huge hit and by 1927 allowed the company to expand their portfolio and try out some new designs. By 1929, the company’s first twin lens reflex (TLR) called the Rolleiflex was released. Although twin lens designs had existed before the Rolleiflex, Franke & Heidecke’s new camera would set the standard for which all TLRs would follow, both from a design and functionality standpoint.

By the early 1930s, the Rolleiflex would become an immediate hit and would have unparalleled success over the next several decades. Like the Leica II rangefinder built by Ernst Leitz, the Rolleiflex would become an often copied camera, with models produced by a huge number of German, American, and Japanese companies. Some Rolleiflex clones copied the design very closely, and others changed the formula a bit, but they all retained the same basic shape and form factor.

One of the reasons that Franke & Heidecke was so successful was because of the leadership of both Paul Franke and Reinhold Heidecke. Franke had a keen business ethic which under his leadership allowed the company to secure strong bonds with suppliers and distributors alike. He ran the business efficiently and allowed the business to grow. Reinhold Heidecke on the other hand was responsible for the engineering and design that made the company’s cameras successful. With the combined leadership of both men, Franke & Heidecke was well suited to develop, create, market, and sell their products all over the world.

Unfortunately, in 1950, Paul Franke would fall ill and suddenly pass away, leaving the business to his son, Horst. The younger Franke lacked the leadership and business know-how that his father had, and throughout the 1950s would make several business decisions to the detriment of the company. Buoyed by the success of the Rolleiflex and the engineering prowess of Reinhold Hedecke, the company still remained profitable despite it’s leadership woes.

By the end of the 1950s, Franke & Heidecke’s success started to slow. Professional and advanced amateur photographers already had their Rolleiflexes, and with increased competition from the Japanese camera industry and new 35mm SLRs from Nippon Kogaku, and quality professional cameras from Hasselblad, sales started to stagnate.

In the early 1960s, Franke & Heidecke started to release new products like a slide projector and 16mm camera, but nothing that made any significant dent in the marketplace. It was clear that the company had no good direction for the future and needed outside help.

In 1964, the company now officially called Rollei-Werke, sought the advice of outside sources. A 38 year old German physicist named Heinrich Peesel, produced a detailed report of where he thought the company should head which impressed Rollei leaders so much, that he was offered a position as Chairman of the Rollei board of directors.

Peesel’s approach was aggressive and involved a complete 180 of the company’s direction from medium format TLRs into several other markets to which the company had little to no experience. It is said that Peesel reviewed a large number of ideas for new products that the company had thought up, and of those, only three were built – a Rolleiscop slide projector, a medium format 6×6 SLR called the SL66 which competed with the Hasselblad 500C, and a 35mm miniature camera called the Rollei 35.

At first, Peesel’s aggressive plan seemed to be working. Investors and customers were excited about the new products, and upon it’s debut at the 1966 Photokina, the Rollei 35 was the smallest full frame 35mm in the world. Sales immediately flourished and the company began a period of expansion into larger factories and hiring more employees anticipating great demand.

After the release of the Rollei 35, Heinrich Peesel held a meeting with the design team at Rollei and declared that their next project must be a 35mm SLR camera. It is said that in this meeting, Peesel brought with an Asahi Pentax Spotmatic because he was so impressed with the quality, compact design, and controls of the Japanese camera that he wanted it to be the basis for Rollei’s new camera.

For a company looking to expand it’s product lineup, a 35mm SLR may have seemed like the logical next step, however Rollei faced incredible competition in the market, which was something they weren’t used to. Since it’s inception, the cameras made by Rollei (Franke & Heidecke) dominated their respective markets and saw little competition. They were one of the first German companies to make medium format stereo and TLR cameras, their slide projectors and 16mm cameras were in markets that didn’t see a lot of competition, and although the Rollei 35 was in a crowded 35mm market, it’s incredibly small size was unique in the marketplace and allowed it to stand out.

A new 35mm SLR would need to not only stand out from the dozens of German leaf shutter SLRs that were already being produced, but also the huge number of Japanese SLRs that had flooded the market. Another obstacle was that the initial momentum gained by Peesel’s new ideas had started to slow. Sales of Rollei’s new products were modest at best. The Rolleiflex TLR, once the company’s bread and butter, saw it’s sales start to crawl. The design and engineering team assigned to create the new 35mm SLR was given inadequate time and money to fully realize their vision. As a result, some sacrifices needed to be made.

Released in 1970, Rollei’s new 35mm SLR was called the SL35 and was first produced in Germany. The camera succeeded in mimicking the Spotmatic’s compact size and good ergonomics. At a glance, the two cameras were nearly the same size, shared similar rounded corners (as opposed to the sharp corners favored by many Japanese models), had a similarly shaped prism, had flash contacts in the same location, and in the case of chrome models, had similar looking black shutter speed and rewind knobs.

Another similarity which wasn’t externally obvious was that although the Rollei had an all new bayonet mount, it used the same exact method for stopping down the lens and with an M42 to Rollei QBM adapter, M42 lenses for the Pentax could be mounted to the Rollei and still use the automatic diaphragm feature, something that no other adapted lens was capable of.

The Rolleiflex SL35 succeeded in being built to the high standards of quality that customers expected from a camera bearing the Rolleiflex name. They also succeeded in creating a clean and functional design reminiscent of Japanese cameras. Gone were any German “eccentricities” and odd design elements that were common with pretty much every other German SLR ever made.

Unfortunately, with the limited resources afforded to it’s designers, the Rolleiflex SL35 lacked several modern features that customers expected at the time, such as open aperture TTL metering, automatic exposure, and full (or partial) information viewfinders. Using the built in meter required the use of a separate button next to the shutter release which would stop down the lens and take a meter reading. The photographer would have to press this button to use the match needle system, get the exposure right, and then move his or her finger over to the separate shutter release button to expose an image. The viewfinder, although bright and easy to see through, lacked any information about the selected shutter speed or aperture values. These characteristics were status quo when the Spotmatic first made it’s debut in 1964, but by 1970, customers expected more, especially for a camera with a premium price tag like the SL35.

Originally selling for “around $300” (I was never able to find an exact price in my research), when adjusted for inflation, this is over $1900 today. Imagine buying into a new SLR system today for nearly two thousand dollars and having technology that was common a decade before. Sales crawled for the Rolleiflex SL35, and between 1970 and 1972, an estimated 24,500 were made.

Anticipating a high production cost in Germany, Rollei thought it could save money and thus lower the price of the SL35 considerably by moving production of the camera to Singapore where labor rates were considerably less than they were in Germany. In a New York Times article published on August 1970, it was estimated that the cost savings of producing the camera in Singapore meant that the price could be lowered to about $210 making it more competitive. Heinrich Peesel was quoted in the same article saying that the competitive advantage of producing cameras with labor rates comparable to those of the Japanese would allow Rollei to capture at least 10 to 12 percent of the market.

That never happened.

Production for the Rolleiflex SL35 shifted to Singapore in early 1973 and would remain there for the duration of the model’s existence. Despite training the Singapore factory workers in Germany, and using the same processes that the German factory did, quality control for the Singapore models suffered. None of the specifications of the camera were supposed to change between German and Singapore models, but it is said that the German models are heavier and have a better build quality.

The drop in price did help as sales for the SL35 steadily increased until it’s discontinuation in 1976. According to Wikipedia, a total of 333,000 SL35s were made during it’s entire production run. Assuming that number is correct and there were 24,500 models made in Germany, it means 308,500 were produced in the 4 years it was made in Singapore.

In the early to mid 1970s, the entire German camera industry was in disarray. Long time German companies like Zeiss-Ikon and Voigtländer were closing their doors and in an attempt to consolidate it’s resources, Rollei would purchase Voigtländer from Zeiss and eventually release a follow up to the SL35 called the Voigtländer VSL series, that at first used the M42 screw mount, but later was adapted to use the Quick Bayonet Mount of the SL35.

The SL35/VSL series would remain in production until about 1980 launching a few variants. First came the SL350 in 1974, a higher end version of the SL35 with open aperture TTL metering, a flash hotshoe, and an improved viewfinder, and then in 1976, the SL35M and SL35ME which were wholly updated versions of the original model, and finally in 1978, the SL35E which was an electronic version of the SL35M.

Rollei would abandon the 35mm SLR market in 1981 (some sources say 1980) as demand for German made SLRs had all but collapsed. By then, a few high end Japanese makers like Nikon and Canon dominated cameras sales with little room for another premium competitor.

Heinrich Peesel would leave Rollei in 1974 and would be replaced by what would turn out to be a revolving door of executive management. Perhaps mirroring Rollei’s camera struggles, the whole company was in disarray and continuously lost money.

In April 1981, the company was sold once again to Hannsheinz Porst who owned his own retail photo company called Photo Porst. This move was seen as a desperation move as Porst was already struggling financially. In an effort to use the acclaimed Rollei name to boost his sales, Porst discontinued many of Rollei’s products, focusing entirely on basic 35mm viewfinder cameras, and a few medium and high end Rolleiflex models.

The Porst era would not last long as support from consumers and the rest of the industry was non-existent. As a result, less than a year later, the assets of Rollei were liquidated and various parts of the company were sold off to various sources.

At this point, I’ll spare you any more narrative of what happened next, as it’s quite depressing. Wikipedia’s Rollei article has a lot of detail about the various ownership changes and struggles the company had and would continue to have, so if you’d like to read more about how a once prominent maker of some of the world’s finest cameras was reduced to a trademark shell of it’s former self, you can read about it there.

Today, the Rolleiflex SL35 and the entire SL35 series occupy a rather odd place in the history of photography. Most collectors covet them as they are a fine marriage of German engineering and Japanese design. To their credit, every single lens ever made with the Rollei QBM was excellent. In total, just over 35 lenses were produced, most by Zeiss, and a few by Schneider. A common kit lens for the SL35 was the 7-element Zeiss Planar 50/1.8 lens which was a very capable lens.

German made SL35s are much more desirable than the later Singapore ones both for their better build quality and rarity, and to have a working copy is not easy to find. Still, ask 100 photographers to name the first camera that they can think of when they hear the name “Rolleiflex” and I bet none of them will list the SL35. There are likely many who never knew this camera existed. It was but a footnote in the whole history of the Rollei brand so putting a value on these is not easy. Whether they’re rare or valuable or not, they are neat cameras and worthy of notice if one ever crosses your path.

My Thoughts

Another SLR, another lens mount….ugh. I guess exceptions can be made when you’re talking about a marquee brand like Rolleiflex. Except this isn’t just any Rolleiflex, a brand most commonly known for their medium format Twin Lens Reflex cameras which were produced from 1929 through 2000. This Rolleiflex SL35 is from a short lived series of 35mm SLRs that Franke & Heidecke (the company didn’t adopt the ‘Rollei-Werke’ name until 1972) produced from 1970 through 1981.

The SL35 was the first model in the series and used a proprietary bayonet mount simply called the Quick Bayonet Mount. QBM lenses were not used on any other series of camera other than the Rollei SL-series and the badge engineered Voigtländer VSL series from about 1976 – 1980.

For starters, the SL35 is not a large camera. It is said that the designers of this model took inspiration from the Pentax Spotmatic and wanted to build a camera that would compare favorably to the best Japanese designs of the day. The SL35 feels very sturdy in your hand, but is surprisingly light weight. At 594 grams, the body is lighter than a Pentax Spotmatic at 624 grams, Minolta SRT-101 at 712 grams, and a Canon EF at 743 grams, all cameras that would have been available at the same time as the Rollei.

The camera has clean lines with nicely curved edges that are less likely to show dings if the camera takes a bump while out in the field. It features an uncluttered layout which is uncharacteristic of German made SLRs which often were based of leaf shutter rangefinder bodies. The whole look is clean and much more Japanese in design.

The team at Franke & Heidecke who were charged with designing a new 35mm SLR were given inadequate time and budget to come up with a lot of new technology, so what they decided to do was rather than create a complicated state of the art camera, they would use their considerable effort building high quality and precision medium format cameras, and design their new SLR with a similar level of quality and design. This camera is chock full of small subtle touches of quality that at first, aren’t immediately noticeable. Many of the best parts of this camera aren’t visible from the outside, and the average person might never know are there.

Starting with the outside, the body covering is made of a high quality synthetic material with a deep pebbled texture that after all these years is still grippy, without feeling sticky, and shows no signs of peeling or shrinking.

The top plate of the camera keeps with the clean design featuring from left to right, the rewind lever, automatic resetting exposure counter, combined shutter speed and film speed dials and shutter release, wind lever, and meter activation switch.

It’s that last feature, the meter activation switch, which is the most curious element of the camera. Pressing this button both stops down the lens to your chosen aperture setting and activates the meter, which is shown as a “match needle” in the viewfinder. Debuting in 1970, the Rollei SL35 was released years after many other cameras had incorporated exposure meters with a match needle system. I find it odd that the designers of this camera chose to keep this a separate control and not allow the meter to work without having to first stop down the lens.

Another curious decision is that this meter activation switch is not only much larger than the shutter release, but it’s also coated in slick black plastic and is located in a position exactly where your finger naturally wants to find a shutter release. This results in many erroneous presses of this button when you had hoped to fire the shutter.

The bottom of the camera has the rewind activation button, tripod socket, battery compartment for the single PX625 battery, and three small plastic feet that allow the camera to sit above a flat surface without the metal plate touching anything. The inclusion of these feet mean that in most cases, the bottom plate of the camera wont scuff or scratch like on most cameras. On my particular example, there are only a couple tiny surface scratches which help to keep a nice appearance. The tripod socket is a reinforced part of the main body of the camera, which increases strength and ensures a secure fit when mounted to a tripod.

Loading film into the camera requires a slight upward tug of the rewind knob, and the right hinged door pops open revealing a clean and well thought out film compartment. As I mentioned earlier about all of the nice touches of quality in this camera, there are several in the film compartment that most people would likely never notice unless someone (me) pointed them out to you.

First, the entire film compartment is one single piece of metal. Unlike many cameras where the take up and supply sides are separate pieces from the mirror box, there are no seams, screws, rivets, or anything that would allow dust or light to pass into unwanted crevices of this camera. Having a single piece of metal likely increased production costs, but it also increased rigidity and therefore reliability of the camera.

The film plane consists of two sets of polished rails that allow the film to travel smoothly and unimpeded across the film gate. The pressure plate on the back of the film door is also a solid piece of metal with nicely tapered edges which likely eliminated any possibility of resistance during film transport.

Next, you see the rubber coated cloth shutter curtains. While most cloth focal plane shutter have some kind of rubberized coating to keep light from passing in between the fibers, the coating on the SL35’s shutter has a look that appears to be a step above others I’ve seen. While not as ancient as others in my collection, assuming this example is an earlier model made somewhere around 1970, these curtains are approaching 48 years old and look brand new. I see no hints of cracking, pinholes, or any other anomalies which can often plague other cloth curtains. It’s likely possible that this example was taken care of extremely well, but I do believe that part of the reason that they look as nice as they do is above average construction.

The take up spool has two very large notches on each side which allow for quick loading of the leader on a new roll of film. There are several white arrows near the top of the spool indicating the direction in which the spool will rotate. Some 35mm cameras employ a counter-clockwise or “over” rotation which keeps the film curling in the same natural direction as it’s in when loaded in the cassette, but others like the Rolleiflex SL35, use a clockwise or “under” rotation where the film is rolled opposite of it’s curl in the cassette. Some people believe that this “under” design is superior as by forcing the film to rotate in an opposite direction of how it is in the cassette, will help flatten the film better and eliminate any possibility of film flatness issues.

One last nice touch to the film compartment which likely wasn’t appreciated much when this camera was new, is there are no foam light seals anywhere in this camera. The door hinge has a narrow strip of black velvet to keep light out and the door channels are narrow and very deep so no seal is necessary at all.

The front of the camera features the 12 second self-timer, two PC flash ports for X-sync and FP-sync, and two front mounted strap lugs. The position of the strap lugs on the front of the camera as opposed to the sides, help keep the width of the camera in check, but it was believed that when the camera was supported by the strap, a heavy lens would be less likely to allow the camera to fall forward and get damaged.

While I normally groan whenever I see yet another bayonet lens mount, I can give this camera’s designers credit as the QBM is one of the faster bayonet mounts to install and remove. The lens release is a bright red anodized button near the 5 o’clock position of the lens mount. If you hold the camera in your left hand with the back of the camera facing your palm, your left thumb resting on the bottom plate of the camera, and your right hand gripping the front of the lens, the red release button falls into the exact position of where your right thumb will naturally fall. A quick press of this button with your right thumb and a quick twist of your right wrist, and the lens is off the camera. This is quite a bit faster and easier than other mounts like the Olympus OM mount which require the press of a tiny button on the lens, the Minolta SR mount which has a small little slider awkwardly located at the lens mount’s 3 o’clock position, and the incredibly frustrating Canon FD breech lock mount which can easily jam a lens permanently on the body of the camera.

Another really cool feature of the QBM that hearkens back to the Pentax Spotmatic which Franke & Heidecke set as the benchmark for this camera, is that an M42 -> QBM adapter was created for this camera which retains full compatibility with the automatic diaphragm feature of those lenses. Like on all Pentax M42 mount SLRs with an automatic diaphragm, there is a pin at the 6 o’clock position of the lens that is triggered by a moving button inside of the mirror box that will automatically stop down the lens the moment before firing the shutter. This means that anyone who already had a collection of M42 lenses could use them on the Rolleiflex SL35 with the adapter with no loss of functionality. I cannot think of any other lens mount that retains this feature using a lens mount adapter like this.

The viewfinder of the camera is rather basic but very functional. I found the focusing screen to be bright and easy to see focus on. The only focusing aide is a microprism circle in the center of the screen, and although I generally prefer split image aides, I had no problem seeing focus when shooting the SL35. Other than the match needle system on the right side of the viewfinder, there is no other information visible.

There are several other nice touches to this camera that help maintain this camera’s lofty standards of build quality. The mirror box has extra dampers and seals allowing for a quieter than average noise and minimal vibration when firing the shutter. The wind lever has a moderate level of resistance that feels smooth and natural when advancing the film. Even the texture of the chrome plating feels smooth and almost silky under your fingers.

It is clear that the engineers and designers at Franke & Heidecke put a lot of love into making this camera as good as they could. It may have seemed a little behind the times from a technology standpoint, but what it lacked in the form of TTL open aperture metering, a full information viewfinder, and automatic exposure, it made up for in quality.

My Results

My first opportunity to shoot the Rolleiflex SL35 came in early fall of 2017 when I took it with me on a trip to visit family in Michigan. Summer weather was quickly fading but there was still enough good light and color to warrant a fresh roll of Fuji 200. I found that although the meter on the SL35 responded to light, it seemed to be intermittent, so I made the decision to not rely on it, and instead shot the entire roll using Sunny 16.

As promised, the Zeiss Planar lens delivered a whole roll of sharp, brightly colored, and properly exposed images. Of course the images look great you probably thought to yourself! From the moment I first held the Rolleiflex, it was less about whether the images it would produce would be any good, but rather, whether I would enjoy using the camera.

Despite it being nearly half a year since shooting that first roll, I am still undecided. The Rolleiflex SL35 is a quality instrument. It was built by a company that was no stranger to making high quality cameras. The more you hold the SL35 and look at all of the small details in the camera, the more you appreciate the workmanship in it.

Yet, while shooting a camera, does anyone ever say “Gee, this reinforced tripod socket, or finely tapered pressure plate, or red anodized lens mount release button is really making my photography better!”

It’s about the usability of a camera, and that’s where the SL35 comes up short. I realize there were (and probably still are) fans of this camera who took no issue to the separate stop down/meter button and the shutter release button, but this is something I could never get used to. I didn’t mind the spartan viewfinder as much, but for me, the best cameras are ones that feel natural in my hand and whose controls are instinctively easy to use. When everything else is equal, ergonomics are the one thing that can make or break the experience of using a camera and I hate to say it, but with this camera, it’s broken.

What’s most frustrating is that it didn’t have to be this way. I can appreciate that due to a lack of funding and time, the engineers at Franke & Heidecke who created this camera couldn’t implement things like automatic exposure or metering wide open. Open aperture metering is something Tokyo Kogaku included in the Topcon RE Super in 1963, Nippon Kogaku had it in the Nikkormat FT in 1965, and Minolta had it in the SRT-101 in 1966. The SL35 was in development for 4 years before being released in 1970 and didn’t have it.

Even accepting the fact that open aperture metering wasn’t a necessity for many pro and advanced amateur photographers, the placement of the button was poor. As a photographer, I may or may not need to meter every shot, but I am always going to have to press the shutter release. There simply is no reason to have the (optional) button not only be much larger, but also in a more natural location than the (non-optional) shutter release button.

It might seem trivial to base my opinion of an entire camera on one feature, but this is a big one. Not only that, by 1970, there were so many excellent 35mm SLRs that there was little room for error. Had the otherwise excellent Nikkormats or SRTs had such an egregious design flaw, I would have said the same thing about those…but they didn’t.

If you can look past this feature, then you are in for a treat. The Rolleiflex SL35 is one of the finest pieces of craftsmanship in the 35mm SLR market that I’ve ever had the pleasure of using. The camera’s size and build quality are things you notice immediately after picking it up. The viewfinder is large and bright, and of course…that lens! So, if you have an opportunity to check one of these out, I definitely recommend it. Maybe the position of the buttons won’t bother you as much as it did me, but even if it does, I’m sure you’ll agree with me that this is a special camera.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rolleiflex_SL35

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Rolleiflex_SL35

http://elekm.net/pages/cameras/rolleiflex_sl_35_e.htm

http://www.klassik-cameras.de/RolleiflexSL35.html

http://www.stevehuffphoto.com/2012/09/03/film-the-west-german-rolleiflex-sl35-by-ibraar-hussain/

http://www.nadir.it/ob-fot/ROLLEI_SL35/articolo.htm (Italian)

I always wondered what was the hidden feature of those discreet looking Rollei SLRs. Well now I know there is none! Except maybe premium quality build and materials. Thanks for the article!

Hi there,

Fascinating information on the Rolleiflex camera.

Would you be able to help me on some queries I have on the SL35

Thank you

Toni

Hi, I am in the UK. I have read your excellent review of the Rolleiflex SL35.

I have one superb SL35 serial 4042202 made in Germany version.

I have had several other SL35 made in Singapore (the type with the rounded pentaprism top) none of them worked properly.

Taking the baseplate off both, the mechanics inside are completely different. No component visible is interchangeable. Somebody thought that the Singapore version was based on a Cosina.

I did have a photo of the two side by side somewhere.

Richard, that’s very interesting! This suggests that the switch from Germany to Singapore was a lot more than a simple relocation! They likely simplified the design! If you ever happen to find the picture of the two side by side, please send it to me, as I’d like to include it in the review to show people.

Thanks for the info!

Hi There, Very good review on rollieflex sl35. I really love the simplicity of this camera so i bought a used but mint condition one body that is made in Germany then bought a lens from different seller. I thought I was so lucky considering that the Germany made was so rare to find especially the black ones. But maybe I was unlucky as I struggle to find the focus on something. to make matter worse it is not a split image focus screen so I was really frustrated. So i decide to returned the Lens I bought to the seller as I thought it was defective then bought another one but It was still the same.It is like focusing on DSLR that diopter needs adjustment. Even if I have pinned the focus distance to the subject it still appeared very soft. So I would just like to asked if this is different from what you have experience on you camera and that if this is still repairable or Would i bought a new used one. I hope you can help on this as I was really desperate for any feedback to help me decide if I should just bin the camera as it is useless anyway. Thanks

There isn’t anything fundamentally different about the SL35 that would make it focus any different from any other SLR. Not having the split image focusing aide you’re used to can make a difference if you have poor vision and struggle to “see focus” when looking through an SLR, but I would expect that most people can get accurate focus without one. If your SL35 absolutely does not get anything in focus, there’s likely something wrong with the camera. Perhaps the focusing screen inside of the viewfinder is out of position or damaged. Even a fraction of a millimeter difference can make things wildly out of focus. I also once had an SLR that was inexplicably missing the film pressure plate on the inside of the film door. I did not notice this until after shooting a whole roll where nothing was in focus because the film was not flat across the film plane, so I would check that too. Otherwise, I have no other suggestions. Good luck!

Hello,

Very interesting article about the SL35 and especially the history of Rolleiflex. I have recently bought an SL350 without really knowing much about this camera and brand except for the medium format and the Rollei 35.

I would love to read an article especially about the SL350, it is very hard to find reviews on it and so far, it seems like a camera that deserve a review. Mine was made in Germany and I can tell by the built quality that they were serious about having an impact in the 35mm market.

Very best,

Hedi

Excellent and very detailed article, thanks! Sadly mine has stopped working, perhaps electronics. Any idea who might be able to get it working again pls? (Incidentally i also have an autowinder which clips to the bottom!)

Sadly, repairing these electronic German cameras is very hard to do. I honestly couldn’t even begin to suggest someone. My advice would be to reach out to Allen Wade at Cameraworks in Latham NY. You can probably google his info as I know he repairs a wide variety of camera makes.

HELLO, I have had the occasion of having a Rollei QBM Planar lens repaired with a chinese guy in Singapore. He has worked a few years for Rollei and he might be able to help you. DE Camera Consultant M. Philipp TAY mail: enquiries@decameraconsultant.com http://www.decameraconsultant.com Phone: +65 96311888

I hope you will read this message….!

Good article, but I’d clarify a few things. First, the Voigtlander VSL 1 and 2 were not based on the design of the SL35, but on the Zeiss Ikon SL706, itself a derivative of the Zeiss Icarex. The Rolleiflex SL35M and ME were also based on this design. I’m lucky enough to own a German-made SL 35, and while it’s had a few reliability issues, I enjoy using it. The viewfinder in particular is excellent, as good as if not better than that of an OM-1, and better than any other camera made at the time short of a Leicaflex.

Thanks for the clarification Walter. Having never had the pleasure of shooting or even handling a Voigtlander VSL, it’s often difficult to trace the lineage of these less common models!

Thanks for this post, even though I am a few years behind. I owned two SL35 German bodies and quite a few lenses starting in 1973 and used them faithfully for 35 years until I just wore them out and my repair guy retired. They were amazing cameras. I was going to by the Olympus OM-1 then saw the SL35 in Talls camera in Seattle and I was hooked. I think whether you like the stop down metering or not depends on what you had before. I can see maybe going backwards might be a problem, but I did not know any better and was happy to have TTL metering vs my Edixa that I was shooting at the time. I always thought of it as a feature rather than a hinderance. In fact, I rather enjoyed getting a preview of the depth of field with each shot that I metered. And a battery would last years in the camera because there was no constant drain from the meter. The lenses (German Zeiss) were outstanding, as good as my friends Leica M3 glass. In the camera club I belonged to at the time (mid-70’s to early 80) I was able to get two other people to buy SL35’s, so we had our own private sub-club. I replaced it with a Leica R8 in 2010 when they both were getting too expensive to maintain, but to this day I often look on the internet to see if I can find one that I might buy, but most of what I see are Singapore models or well-worn German ones at too much money. Don’t shoot much film anymore, so probably will never get another one, but I truly enjoyed my experience with the camera. Best I might do is get a few lenses for my Nikon Z. Thanks for the trip down memory lane.

I agree with Aram Langhans views regarding the stop down metering. I would also like to point out that thanks to stop down metering M42 lenses with QBM adapter would behave exactly like the original Rollei QBM lenses as far as metering is concerned. This might have been important to a lot of potential buyers at the time.