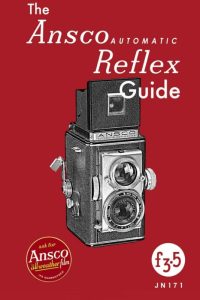

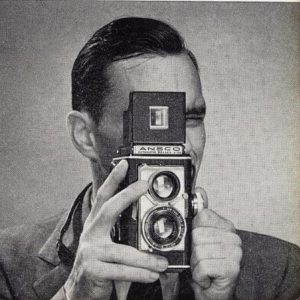

This is an ANSCO Automatic Reflex 3.5 twin lens reflex camera, made by ANSCO of Binghamton, NY starting in 1947. It shot 6cm x 6cm images on 120 format roll film and had a feature set that compared favorably to top tier TLRs from Germany. The ANSCO Reflex was an ambitious camera not only for ANSCO, but the entire American camera industry and originally sold for $275 in 1947, which put it far beyond the reach of the typical consumer. The camera has a unique look and excellent ergonomics, but it was plagued with reliability problems, and it’s extremely high price led to poor sales. It was only in production for about 5 years before being discontinued.

Film Type: 120 Roll Film (twelve 6cm x 6cm exposures per roll)

Lens (taking): 83mm f/3.5 Wollensak Ansco Anastigmat coated 3-elements

Lens (viewing): 83mm f/3.2 unbranded coated lens

Focus: 3 feet 8 inches to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coupled Waist Level Reflex Viewfinder

Shutter: Wollensak Rapax Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/400 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: ASA Port Flash M-Sync

Weight: 1289 grams

Manual: https://mikeeckman.com/media/AnscoAutomaticReflex35Manual.pdf

How these ratings work |

The ANSCO Automatic Reflex 3.5 was not only ANSCO’s most ambitious camera they ever made, it was also the highest quality precision TLR ever made by an American company. Designed by famed industrial designer Henry Dreyfuss, the ANSCO Reflex shares little in common with other, more established German TLRs. It has several unique features not found on other TLRs, and with a 9-speed shutter and 83mm Wollensak triplet, the camera was capable of very good images. I think it’s one of the best looking cameras ever made, is surprisingly easy to use, and makes outstanding photographs. This is a camera that every collector should have in their collection. Highly recommended! | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 30% | |

| Bonus | +1 for the complete package, innovative, and one of the best looking cameras ever made | ||||||

| Final Score | 14.0 | ||||||

History

ANSCO was the name of a prominent film company based out of Binghamton, NY throughout most of the 20th century. The name “ANSCO” is actually an abbreviation of sorts for Anthony Scovil & Company which were two American companies that merged together in 1902. I’ve covered the origins of ANSCO numerous times in reviews I’ve written for this site, so if you’d like to know more about the company’s history, read my review for the Anscomark M, and the ANSCO B2 Commander.

For this article, we’ll start right after the end of World War II. ANSCO’s relationship with AGFA and it’s parent company GAF was strained. The German assets of AGFA-ANSCO were seized in 1941 by the United States government and placed under control of the US Treasury Department under the Office of Alien Property Custodian. After the war, ANSCO was allowed to continue to release AGFA designed models, but getting anything built in Germany was impossible, so new camera production was solely placed in ANSCO’s hands.

Because of heavy damages and uncertain political restrictions over Germany and most of Europe, there was a void of high quality cameras being produced. Several American companies like Clarus, Vokar, and even Argus rushed new models to the market in the hope of attracting the buying dollars of semi pro and professional photographers.

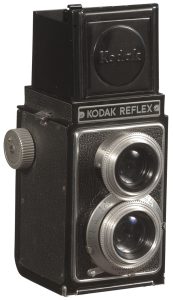

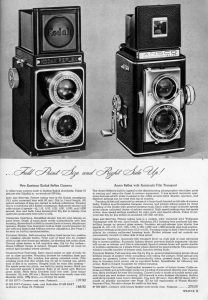

In the twin lens reflex segment, Kodak had released it’s all new aluminum bodied Kodak Reflex in 1946 with externally coupled viewing and taking lenses and a Flash Kodamatic shutter. The later Kodak Reflex II from 1948 upgraded the model with a more capable shutter, and their own 4-element f/3.5 Anastar lens.

Although a solid performing camera, the Kodak Reflexes were still miles away from the quality and innovation of German TLRs like the Rolleiflex and pre-war Voigtländer Superb. That left ANSCO as the sole American company who made an attempt to release a top of the line professional TLR.

NOTE: A large amount of the information below comes from David Anderson’s excellent Ansco Automatic Reflex website. David is also the author of probably the world’s only authoritative guide to the ANSCO Reflex.

In the November/December 1945 issue of ANSCO’s company magazine the Ansconian, they announced development of an exciting and high-spec TLR that would be made entirely in the United States and would compete with the best German cameras. ANSCO took out advertisements in a variety of publications such as Popular Photography, Life, National Photo Dealer, and Time magazines where they suggested that their new camera had been in development for 6 years and was designed with feedback received from the US Army Signal Corps. The camera was promised to dealers by June 1946 and that it would sell for around $100. Both of these promises turned out to be overly ambitious statements from ANSCO, a company more widely known for their film stocks and simple folding and box cameras.

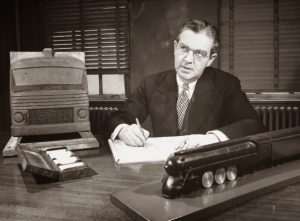

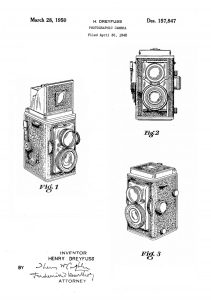

For their new camera, ANSCO turned to industrial designer Henry Dreyfuss, who had worked with ANSCO before, designing many of the company’s film packaging. Dreyfuss’s other works include New York Central Railroad’s streamlined Mercury locomotive, the Hoover Model 150 vacuum cleaner, various John Deere tractors, Western Electric and Bell Systems telephones, the iconic Honeywell “round” T87 thermostat, and even the Polaroid SX-70 Land Camera.

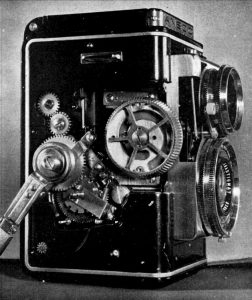

In designing the new camera, Dreyfuss valued the input of both engineers and designers in making a camera that never sacrificed usability or performance. He did not base any part of the camera off any pre-existing German or American designs. A priority for him was to make all of the camera’s controls easy to use with the camera at waist level and he wanted as many of the camera’s controls to be ambidextrous to comfortably accommodate as many users as possible. Both the shutter release and cocking levers were in a position that could easily be reached with either your left or right hand. He valued style and grace, giving the camera as many rounded corners to give the illusion of a smaller and “softer” camera.

From an engineering standpoint, the entire body is made of a cast aluminum alloy body with tolerances so tight, screws or other rivets were not necessary to hold it together. The front lens standard improves on the designs used in German cameras by way of four self-lubricating grooves, two on each side, that are driven by cams on each side of the camera. The lens board is connected at four suspension points that was said to eliminate torque and be completely resistant to wear. ANSCO claimed that under normal use, the focus movement of the camera should remain smooth indefinitely.

All of the exposed gears and tactile points were heat treated to improve hardness, and machine cut to exact specifications to ensure the highest degree of fit and finish. Most moving parts of the camera use bronze bearings pressed into the aluminum frame to improve the dependability of the camera.

Finally, the ANSCO Reflex had a unique feature in the film compartment that used safety catches which would hold both the take up and supply spools in place so that they could never fall out of position when the camera was closed. This virtually guaranteed that there would never be a film transport problem after the camera was put into use.

Mock-ups of the ANSCO Reflex appeared as early as late 1945 suggesting the general appearance of the camera was settled early on, but production and bureaucratic delays plagued the eventual release of the camera. The image to the left shows an early mock-up made out of wood, which featured an all black body and lens board, no name plate, different styles of shutter release, a wire frame finder, and the lack of symmetrically exposed focus knobs.

A combination of ANSCO’s inexperience with making a precision camera and strict, bordering on overbearing, oversight from the government, every move by the company was scrutinized by the Alien Property Custodian, funding was difficult to acquire, and a lack of experienced optics engineers continually brought design and manufacturing to a halt.

In addition to ANSCO’s shortcomings, they also had no ability to design their own shutters or lenses. For that, they partnered with Wollensak, who was at the time the premiere maker of American shutters and lenses. The shutter used was the Wollensak Rapax which had been used in other American cameras made by Ciro, Argus, and others. The lens was an 83mm Wollensak Anastigmat f/3.5 triplet which was chosen as a cost cutting measure. Where most German TLRs used 75mm lenses, the slightly longer focal length of 83mm meant that the edges would show less sharpness drop off or vignetting, allowing them to use a less expensive 3-element lens than costlier 4-element designs.

The first ANSCO Reflex cameras started to roll off the assembly line in February 1947, but problems with distribution meant it would take another 9 months before any would be sold to the public. The new camera would finally be released on November 5, 1947, nearly 2 years after it’s original announcement, and would be officially called the ANSCO Automatic Reflex 3.5. True to their word, the new camera was innovative and matched many of it’s German competition in terms of features, but unfortunately, the cost of the camera spiraled well beyond the projected price of $100. Appearing in the 1948 Montgomery Wards catalog for $275, the camera was more than double that of Kodak’s TLR. When adjusted for inflation, that price compares to $2875 today, hardly a price for the casual photographer!

Despite the unexpectedly high price for the camera, the ANSCO Reflex generated a lot of excitement and praise from the photographic community. The camera was available for purchase four days prior to the national roll out by Binghamton residents because of their prolonged support of the company, and the first official sale of one was to Binghamton mayor, Walker B. Lounsbery.

In the months that followed, the camera enjoyed positive reviews, but it’s high price limited it’s sales. Although no official numbers were kept, David Anderson estimates a total of around 10,000 cameras were made.

Below is a hi-res scan of a full review from the February 1948 issue of Minicam Magazine (the predecessor to Modern Photography). The whole review is 8 pages. Click on each image to see a full size 3500px scan of each page. Special thanks to Marc Bergman for these scans.

Shortly after it’s release, the Reflex received it’s one and only update, which was the addition of a flash sync port. Collectors today refer to the original models as “Type 1” and ones with a factory flash sync as “Type 2” Reflexes. After the release of the Type 2 Reflexes, ANSCO offered an upgrade for $25 where owners could send their cameras back and have it factory modified to include the sync port. Both Type 1 and Type 2 Reflexes were sold concurrently.

All Type 1 Reflexes have a serial number beneath the shutter that begin with a 0 or 1. Type 2 Reflexes all have serial numbers that begin with a 2. There were a small number of “hybrid” Reflexes that were built with a ‘1xxxxxx’ serial number and no sync port, but were factory modified before they were sold, and have a ‘2-‘ before the ‘1xxxxxx’ serial number. If you have a Reflex with a serial number that does not begin with a ‘2’ or ‘2-‘ but has a sync port, then you know it was later modified.

It is not clear exactly when ANSCO ended production of the Reflex, but the final nail in the coffin was likely ANSCO’s release of the very basic $15.95 Anscoflex “Pseudo-TLR” camera in March 1951. By this time, German exports were in full swing, and people looking to spend top dollar on a TLR camera would have had no problem getting their hands on a Rolleiflex or comparable model.

The ANSCO Reflex succeeded in proving that an American company could build an innovative and high quality twin lens reflex camera, but it was ultimately seen as a failure. It’s two year production delay after it’s original announcement in 1945 meant that ANSCO was unable to fully take advantage of Germany’s inability to produce cameras after the war. Imports of Rolleiflex and Rolleicord cameras began to show up in America in March 1947 beating ANSCO to the market.

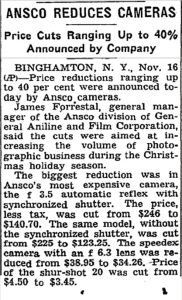

Although the Wollensak shutter and lenses were good, they were still considered inferior to the quality and precision of German built shutters and lenses which made it difficult to justify the camera’s high price. In a last ditch effort to attract new customers, in November 1949, ANSCO would slash prices of Type 2 Reflexes to $140.70, and Type 1 Reflexes to $123.25.

Today, the Reflex enjoys a very positive reputation among collectors, not only because of it’s rarity, but also because of it’s distinct looks and unique design. Imitation is the greatest form of flattery, and the overwhelming success of the Rolleiflex and Rolleicord TLRs meant that nearly every other TLR took design cues from it, but not the ANSCO Reflex. Henry Dreyfuss’s insistence in creating an all new camera that took no styling cues from existing models means that there is no other camera like it.

The ANSCO Reflex isn’t easy to find, and as of the writing of this review, there weren’t any for sale on eBay. When I checked the “Completed Items” box, 7 sold auctions appeared with prices ranging from $99 to $299. If you have a chance to buy or borrow an ANSCO Reflex, it’s worth considering as not only is it the most technically impressive American built TLR ever made, it’s also gorgeous!

My Thoughts

I am just going to start off by saying, I love this camera. The ANSCO Automatic Reflex 3.5 is in my opinion, the best looking TLR ever made. That’s not to say that other TLRs aren’t attractive, but what adds to the allure of this camera is that it looks like no other. So many manufacturers went out of their way to mimic the lines and general appearance of Franke & Heidecke’s Rolleiflex that they all seem to get lost in the sea of never ending Rollei clones made throughout the mid 20th century.

Not the ANSCO Automatic Reflex 3.5. This camera was a by product of post war American pride in the late 1940s. We had defeated the Germans, and it was time that American companies showed their manufacturing and design prowess and released a top tier American built twin lens reflex camera. It had to be big and heavy, it needed lots of chrome, and it needed exposed gears (cue Tim Allen grunting here).

I had first seen one of these beauties several years ago, but was dismayed at the prices that they regularly go for. Good condition cameras are typically in the $150 – $300 range, well beyond the budget minded price range I stay within. In early 2018, I was talking to fellow collector Kevin Murray on the Facebook Vintage Camera Collector’s group and Kevin agreed to send me his ANSCO Reflex for review. Within seconds of his message, I replied back with a resounding yes, and a couple days later, I had a red, white, and blue package from the US Postal Service on my door with an ANSCO Automatic Reflex inside.

Upon removing the camera from the packaging, I was immediately impressed. I’ve always thought the camera looked great in pictures, but once you see the camera in person with it’s satin brushed metal body, grippy morocco grain leather, soft rounded corners, and beautifully sculpted name plate, I had a new appreciation for the design that Dreyfuss put into camera.

The second thing I noticed was how large and heavy the camera is. The ANSCO Reflex is both larger and heavier than almost any other TLR in my collection. On a shelf, it stands above my various Rolleiflexes and other TLRs made by Yashica, Meopta, and Minolta. Weighing in at 1289 grams (just under 3 lbs), it is substantially heavier than the Meopta Flexaret VII (994 g), Rolleiflex K4A (978 g), Minolta Autocord (973 g), and Yashica D (957 g). In fact, for me to find a twin lens camera heavier than the ANSCO Reflex, I had to step up to the behemoth Mamiya C3 Professional which tips the scales at a whopping 1826 grams!

Fearing that the large size and weight of the camera would hinder it’s use, the third thing I noticed was how thoughtful the camera’s controls were. Once again, credit goes to Henry Dreyfuss for taking into consideration the usability of the camera in it’s design. The ANSCO Reflex is chock full with ergonomic subtleties that aren’t obvious until you handle the camera.

Starting with the film advance lever, you might not immediately notice it, but the center axis of the handle is near the back of the camera, rather than the middle, like on pretty much every other “Automat” style TLR. The reason for this is to allow for the internally geared handle to advance the camera at any position 360 degrees around it’s rotation. You never need to “back-wind” the handle to get back to the starting position before advancing the film. You can advance the film with the handle pointing up, down, or anywhere else that you find comfortable. Turning the crank advances the film to the next exposure and automatically stops when you’ve reached it.

Unlike most German TLRs, the film advance crank does not automatically cock the shutter as this requires a separate lever on the shutter. Although this sounds like a step backwards, there is a practical benefit to this as it allows you to advance your film immediately after your previous shot without having to cock the shutter and leave the springs tensioned in between shots. It was common practice with most TLRs to always advance the film after the previous exposure to avoid potential film flatness issues as the film goes around the 90 degree bend from the supply to the take-up spools. Chiyoda Kogaku alleviated this issue on the Minolta Autocord by reversing the location of the supply and take up spools compared to a Rolleiflex so that the film would only make the 90 degree turn after the image was exposed. With the ANSCO Reflex, the film travels in the same direction of the Rolleiflex, but you can safely advance the film after your exposure, and then let the camera sit for as long as you like and cock the shutter when you’re ready for the next photo. Whether this was an intentional design element of the camera, or a creative way ANSCO’s marketing department “turning lemons into lemonade” with a less advanced shutter is anyone’s guess.

Cocking the shutter was done via a lever to the right of the lenses (when looking at the front of the camera). This was comfortably located within easy reach of the photographer’s left thumb while holding the camera at waist level. Opposite of the cocking lever, near the photographer’s right thumb is the identically designed shutter release.

The ANSCO Reflex has 3 different methods for adjusting focus on the camera, a traditional knob on the camera’s left side, or two external gears near both the cocking and shutter release levers. Interestingly, the focus knob on the side of the camera is removable to improve portability of the camera in a bag. When purchased new, the camera included a large flat head screw that would take it’s place. This arrangement of the focus knobs, the cocking lever, and the shutter release means the photographer never has to move either their left or right hands while securely holding the camera.

Changing shutter speeds or aperture size requires rotating a ring and a lever around the perimeter of the taking lens. With the camera at waist level, both the selected shutter speeds and f/stops are easily read by an indicator on top of the viewing lens (shutter speed), and through a small window in the frame (f/stops). This arrangement isn’t quite as sophisticated as the dual readout on the Rolleiflex, but it works just as well. There is also a threaded cable release socket to the right of the f/stop readout.

Looking down into the waist level viewfinder offers a life sized representation of the image that would be captured on film upon releasing the shutter. Like all TLRs, the image is horizontally reversed, meaning that as you pan the camera to the left, the image moves to the right, and vice versa. Also like most TLRs, the ANSCO Reflex does not offer any type of parallax correction. Since the view through the viewfinder is not the same lens that will exposed the film, there is a slight vertical error, called parallax, that must be accounted for when composing closeups. At distances beyond 10 feet to infinity, the error is so small, you’ll never notice the difference, but the closer you get to the camera’s minimum focus distance, the greater the error becomes.

The ANSCO Reflex predates the use of Fresnel viewing screens which have laser etched concentric circles radiating from the center of the viewing screen to improve brightness. Instead, the viewing screen is made of glass and is ground in a circular pattern which improves brightness compared to the random sandblasted pattern that most other ground glasses had.

Finally, the viewfinder has both a flip up magnifying glass for critical focus, and a flip down lid with a rectangular window which can be used as a “sports finder” for fast action shots. Although a sports finder was common on most TLRs, they usually were hollow squares in the lid that a photographer would peer through to get an approximation of the exposed image. The ANSCO Reflex was equipped with a glass Newton finder, which was thought to be more accurate.

Loading film into the camera requires an additional step not found on most other TLRs, which is to deactivate the film transport gearing. This is done by setting the exposure counter to the “N / 12” position. The “N” likely stands for “Neutral” or possibly “New”. If you have just completed a previous roll of film the counter should already be in this position, but if it is not, then you must manually set the exposure counter by pressing forward on the metal lever next to the counter, while simultaneously rotating it using the knurled wheel in the center of the exposure counter.

With the counter at the “N / 12” position, the next step is to open the back of the camera by pressing in two door release buttons near the upper left and right corners on the door. This will allow the entire door to swing downward, revealing the film compartment.

Like the Rolleiflex, a new roll of film loads on the bottom of the camera nearest the door hinge, and the empty take up spool loads in the compartment near the top. The ANSCO Reflex has no ability to automatically detect the beginning of the film, so after installing a new roll of film and closing the rear door, you must use the exposure peep hole in the center of the film door and wind the camera until you see the number 1 on the back of the backing paper. When you see that number, you may close the door covering the peep hole as you will not need it for the rest of the roll. The final step is to reset the exposure counter on the side of the camera to the number ‘1’ position by once again pushing forward on the metal release next to the counter and turning the knurled ring. At this point, the camera is loaded and ready to go.

The bottom of the camera has three metal “feet” that slightly raise the camera off the surface of anything you put it on, and a reinforced metal 1/4″ tripod socket. It was probably a wise idea to reinforce the tripod socket as the stoutness of the camera likely would have tore through a weaker mount.

There are a couple other “hidden” features of the ANSCO Reflex that were intentionally designed to improve the photographic experience which might not immediately be obvious. The first is in relation to double exposures. The lever to the right of the exposure counter can be used as an intentional double exposure device. Once you’ve exposed the film, momentarily move this lever to release the shutter lock, then use the front lever to cock the shutter again and fire it for the second exposure. You may repeat this for as many exposures as you like. Although double exposures are possible on most Rolleiflex models, they often require awkward steps to accomplish.

The “N / 12” position on the exposure counter also allows a photographer to change rolls of film partway through a roll by manually setting the counter to this position and then continuously turning the film advance lever without ever having to fire the shutter, until the end of the roll is reached. The photographer could then remove the partly exposed roll from the camera and start over with another.

When you look at all of the individual controls of the ANSCO Reflex you can see that thought was put into each of their location, design, and use. I am pretty confident that anyone reading this review and looking at the images I’ve shared will likely agree that this is a special camera worth considering. What you can’t see in an Internet review and some pictures however, is how well everything works together. Yes, the ANSCO Reflex is big and heavy, but you’ll never notice it while shooting because of how everything comes together for a pleasant shooting experience. I have nothing against the Rolleiflex, or any of the millions of copies that were made by other companies. They’re really well built cameras with excellent optics, but it is clear that there was room to improve the design of the camera. It took an underdog American company and a guy who was better known for designing telephones and locomotives to make a world class handling camera.

My Results

The owner of this ANSCO Reflex warned me that he had tried to previously shoot a roll of film in it and that he struggled with film advance. Knowing this model’s reputation for film advance issues (the user manual actually comments on steps you should take if it acts up) I practiced with the camera using a dead roll of film before getting the hang of it.

My first roll was a fresh roll of Kodak Ektar 100 and I shot it in late spring 2018. For as excited as I was to shoot with this camera, it is big and not exactly portable. Plus being a loaner, I am extra cautious to not take it places where I might need to toss it in a camera bag and risk something happening to it. My extra caution had the side effect of taking forever to finish the roll, but when I did, I was so pleased with the results, I decided to shoot another roll, this time with expired Kodak Portra 800 in it. The gallery below are twelve shots from a combination of those two rolls.

I am going to keep saying it, the ANSCO Reflex is a fantastic camera! I love everything about it. It looks good on a shelf, it feels great in your hands, the controls are very nicely laid out, but now that I get to see the images shot with it’s “lowly” Wollensak triplet, my excitement for the camera has hit a fever pitch.

I was so impressed with the scans of the negatives from the ANSCO Reflex, that I compared them to a recent roll I shot in a Rolleiflex K4A with a Schneider Xenar 3.5 taking lens. In fact, I decided to play a trick on you and admit now that only 11 of the above 12 shots are from the ANSCO. One of them was from that Rolleiflex, and I would be willing to bet that no one reading this review will be able to tell me which one was shot with the Rolleiflex! I will reveal which one it is in the comments below after this review goes live.

Once I got over the shock over how good the images were, I thought that it probably shouldn’t have been so surprising, after all I’ve seen quality images from Wollensak triplets before. Both of my Ciro-Flex D and Argoflex EF TLRs each have a similar lens. In 35mm, I’ve seen great images from the Universal Mercury II, Bolsey B2, and Clarus MS-35 all with their respective Wollensak lenses.

With two rolls of film developed from the ANSCO Reflex and an idea that the images produced by it’s Wollensak Triplet are on par with other great TLRs, I can definitely say this is a special camera. The ANSCO Reflex might have been considered a failure due to it’s high price, its 2 year production delay, and the short amount of time it was available on the market, but if you consider the goal of making a world class American TLR, it was a success in my mind.

We have the benefit today of hindsight to look back on what might have been, and had ANSCO been able to get this out before the Germans were able to resume camera production, and if the camera had been a bit less expensive, who knows what the camera landscape might have looked like today. Perhaps the ANSCO Reflex would have been the first in a line of quality American made cameras that would have competed with the Germans and the new (at the time) Japanese camera industries. Obviously that didn’t happen, but at least we have this one shining example of a truly world class American camera!

Additional Resources

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Ansco_Automatic_Reflex#

http://www.anscoautomaticreflex.com/

http://rick_oleson.tripod.com/index-33.html

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lh-leVbMe00

http://www.dirapon.be/ansco.html (in French)

As promised, the very last image in the gallery of the “Help” graffiti was shot on the Rolleiflex, not the ANSCO Reflex. Pixel peep all you want, there’s no way you’d know any different!

You are not kidding. That lens is impressive. I need to get motivated and use my Rollie.

The “help” photo was my least favorite so I feel like that means something. Haha. Great review, thank you! Now I want one, of course!

I love mine, definitely my favorite of my cameras.

This trip down 6X6 cm Memory Lane reminded me of the family’s Serious Roll film Camera, a Rolleicord V. I’d used this camera after graduating from a Brownie Six Twenty box camera, so I was no stranger to large negatives. In the late 1950’s/early 1960’s, prints were small snapshots, and enlarged prints were rare, so I couldn’t see how much sharper that 75mm f/3.5 Scheider Xenar lens was,compared to the box camera. I didn’t find out how much better until I bought a 6X6 cm. enlarger just as 35mm was taking over the photographic world.

Trying to focus accurately with a (somewhat) “bright center/dim corners” ground glass screen didn’t help things, so I put the Rolleicord away. Years later, I sent it off to Rollei for the “Clean/Lubricate/Adjust” treatment, and got a modern fresnel focusing screen with a split image center, which brought it up to the level of a Minolta Autocord. I used these 6X6 roll film cameras for color and monochrome negative work, since a 6X6 slide projector was a tad too pricey to break out the 120 Ektachrome film.

Great post, Mike! I hadn’t been aware of its existence until I read your piece. Looks like a fun camera to try out. My Fujicaflex Automat weighs 1323 grams (with a roll of film loaded) so it’s in the same heavyweight class with this Ansco. I have this pic posted on my Flickr page for a size comparison to a typical Yashica from the same time period. https://www.flickr.com/photos/127540935@N08/43919814664/in/album-72157699677905001/

The Yashica D pictured is about the same size as my Yashica Flex S so it gives you some idea just how big the Fujica is.

I am glad I was able to turn you onto another terrific camera! The Wollensak triplet on this camera certainly punches above it’s weight. Looking at your Flickr album and my goodness that is a monster! I think the Fujicaflex and the ANSCO Automatic Reflex need to go up head to head in a Japanese heavyweight TLR Battle Royale!

Sounds great!

Early on in your article you mention the camera was plagued by “reliability problems” but then what these problems were/are is never addressed or mentioned. So what exactly were they and were they on-going issues? I’m a big fan of TLR’s having owned and made a lot of money with Rolleis and Yashicamats. Those are gone but still play with a couple of Diacords occasionally.