This is a Zorki 5 rangefinder camera made by Krasnogorskiy Mechanicheskiy Zavod (KMZ) in Krasnogorsk during the years of 1958 – 1959. This particular camera is an early and much less common variant with a red Zorki-5 logo engraved into the body, and a square rangefinder window. Later Zorki 5s had a name plate screwed to the body and a circular rangefinder window. The Zorki 5 was one of the shortest lived of all Zorki models and confusingly was not the successor of the Zorki 4 which was still being produced at the same time. It shared more in common with the earlier Zorki C and Zorki 2C, including that model’s non removable back and bottom loading design. The Zorki 6, which was available at the same time as the 5 is nearly identical except it adds a hinged back and self-timer.

This is a Zorki 5 rangefinder camera made by Krasnogorskiy Mechanicheskiy Zavod (KMZ) in Krasnogorsk during the years of 1958 – 1959. This particular camera is an early and much less common variant with a red Zorki-5 logo engraved into the body, and a square rangefinder window. Later Zorki 5s had a name plate screwed to the body and a circular rangefinder window. The Zorki 5 was one of the shortest lived of all Zorki models and confusingly was not the successor of the Zorki 4 which was still being produced at the same time. It shared more in common with the earlier Zorki C and Zorki 2C, including that model’s non removable back and bottom loading design. The Zorki 6, which was available at the same time as the 5 is nearly identical except it adds a hinged back and self-timer.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 5cm f/3.5 Industar-22 coated 4-elements, collapsible

Lens Mount: M39 Screw Mount

Focus: 0.9 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1/25 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Coldshoe and M and X Flash Sync

Weight (w/ Lens): 600 grams

Manual (Zorki 6): https://mikeeckman.com/media/Zorki6Manual.pdf

Manual (alt version): http://community.fortunecity.ws/marina/marine/569/rusrngfdrs/zorki6/zorki6.html

History

Prior to World War II, the Soviet Union had a variety of optical factories in places like Kharkov and Leningrad that had been churning out some variation of a German made medium format or 35mm camera. One of the core principles of the Soviet government was to be self-reliant and not have to import anything made in other countries.

Early Soviet cameras like the Fotokor-1 were simple 9×12 folding plate cameras made in Petrograd (later Leningrad and today St. Petersburg) that were low quality copies of German designs. The Fotokor-1 was produced between 1930 through 1941 at the GOMZ plant.

The most common 35mm Soviet cameras however, were ones based off the Leica II rangefinder. In the early 1930s, the Leica II by Leitz of Wetzlar, Germany was the most popular compact 35mm camera in the world. The Soviet Union decided they needed to have one too, and between the years of 1932 through 1934, no less than 3 different factories began work on their own copies of the Leica.

Soon, three different cameras, called the Geodezia FAG (pronounced like ‘fuuh g’), VOOMP Pioneer, and the Ukrainian built FED were all put into production. Of the three designs, the FED camera was given the most support.

The FED factory was basically a boarding school that was designed as a youth rehabilitation center for orphaned children. The center was created by Anton Makarenko who was a Ukrainian educator who believed that troubled youths could be productive members of society by combining education and labor in a strict atmosphere. The center itself was named after Felix Edmundovich Dzerzhinsky who was the founder of the Soviet Union’s secret police, known as the NKVD. The NKVD was the predecessor of the much more well known KGB.

Over time, FED would improve both the design and the reliability of the camera, but unfortunately, it’s location in Ukraine meant it was more prone to damage by German fighters in World War II. Anticipating imminent destruction, in 1942 the Soviet government transported much of the FED factory’s machinery to the city of Berdsk, Siberia for safe keeping. Plans for the FED camera were given to another Soviet optics factory called Krasnogorsk Mechanical Works or KMZ for short, in Krasnogorsk, near Moscow where they eventually started producing their own copy of the FED, which they branded Zorki (Зоркий), which loosely translates to “piercing” or “sharp-sighted”.

As predicted, the FED factory sustained heavy damage and would take several years to repair and return to production after the war. Since the KMZ plant was protected from enemy forces, it only took a short order to start producing new cameras. In 1947, the first 35mm rangefinders were built by KMZ in Krasnogorsk. Early copies of the KMZ Zorki still had the FED name stamped into the top plate. Dual FED/Zorkis were produced until the FED factory was restored, and resumed building their own cameras. From this point forward, KMZ built cameras would only have the Zorki name. The original Zorki would remain in production until 1956 and would go on relatively unchanged from the original FED design, which itself was a near copy of the Leica II.

Throughout it’s 30+ years in production, the Zorki would be redesigned and improved several times. Like the FED rangefinder it was based off, the FED too would also receive many changes, but both the Zorki and FED would continue to evolve separately from each other. By the end of their production, the later model FED and Zorkis would share little in common, other than the lens mount.

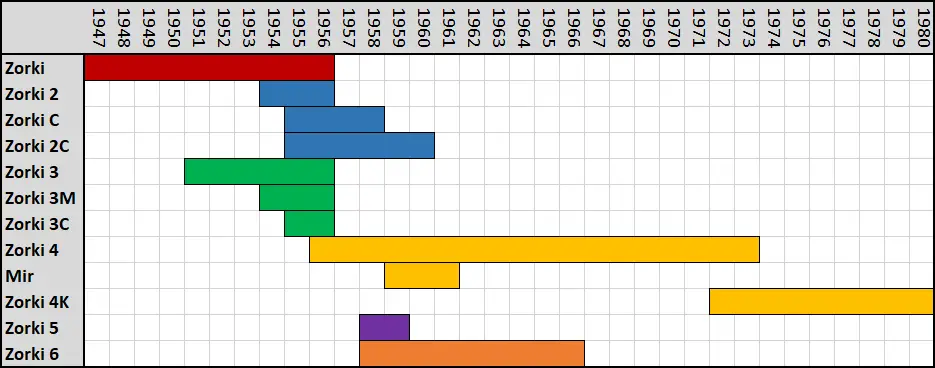

The names given to later Zorkis are quite confusing and were not always indicative to when each model was sold. Many different Zorkis were sold concurrently with others. Further adding to the confusion is that higher numbered Zorkis weren’t always more advanced or “better” than previous ones. The chart below represents all of the various models in the Zorki lineup. Note that there were three additional cameras to bear the Zorki name that are not related to these M39 screw mount rangefinders which I don’t consider to be part of the original Zorki lineage.

As you can see, the Zorki 3 was available three years before the Zorki 2, the Zorki 4/4K were produced well over a decade after the Zorki 5 and 6, and in 1956 you could buy as many as 8 different models at the same time.

The Zorki 3 and 4 series were the first models to have a combined coincident image rangefinder, and (excluding the Mir) were the only models with slow speeds down to 1 second. They all had hinged backs, and in the case of the 4K, had a lever film advance.

The Zorki 5 and 6 were both considered to be replacements for the Zorki 2-series but with a wider rangefinder base and a lever film advance. The Zorki 5 being reviewed here was most similar the Zorki C as it lacked both the self timer and hinged back.

Opinions vary among Soviet collectors as to which is the “best” Zorki since there really wasn’t ever one model with every feature that was once available.

I am a huge fan of the 4 and 4K as they have the largest viewfinder and are easier for me to use with prescription glasses. These models are the most user friendly and were produced in huge numbers, so are easy to find today for a reasonable price (even in the United States). But it’s generally accepted that quality control suffered on later Zorkis so getting a later model that still works can sometimes be tricky. In addition, most Zorki 4s made after 1962 had their name plate and shutter speed markings silkscreened, rather than engraved, which most people consider less visually appealing.

Many people hate bottom loading cameras, so any model with a hinged back is usually preferred over the bottom loading design of the Zorki 1, 2, and 5.

Some people prefer the wider rangefinder base of the Zorki 5 and 6 since a wider base is said to be more accurate.

The slow speed governors used on the Zorki 3 and 4 are especially prone to failure due to misuse or the original lubricants drying up. Models without slow speeds (anything below 1/25 or 1/30) have a higher chance of still working since they lack the clockwork governor that controls the slow speeds.

The Mir could be considered the best Zorki (even though it’s not officially called a Zorki) as it has the user friendliness of the Zorki 4, earlier build quality and engraved markings, hinged back, and the lack of slow speeds, meaning there is a better chance of it working correctly.

As you can see, there is a huge variety in these cameras, which probably explains why some collectors just get one of each, but whichever way you go, it is important to remember that even the newest Zorki is still nearly 40 years old and unless you can get it serviced, or in confirmed working condition, you can’t expect perfection.

Today, the Zorki 5 is likely to be one of the least recommended models, simply due to scarcity. But in terms of the entire Zorki range, these are often considered “go to” cameras for collectors looking for a Leica-like camera that accepts M39 lenses, but without having to pay Leica prices. There are those who would never consider a Soviet rangefinder over anything made in Germany, but therein lies perhaps the biggest advantage of buying and using a Zorki. Since it’s not a valuable collector’s item, you can feel a little more confident taking one out in public and shooting with one, knowing that if something were to happen to it, it wouldn’t be too difficult to get another.

If you are someone who is convinced German quality is the only quality, then there is likely nothing I can say to change your mind. If however, you are looking to get into interchangeable M39 mount “Leica-style” cameras, but without the “Leica-price” these are a great place to start.

My Thoughts

I had the opportunity to shoot the Zorki 5 at the same time as I was working with the Leica Ic earlier this summer. Being the first two Barnack style cameras I’ve used, it was interesting to be able to compare the two side by side. I’ll start by saying that the build quality of the Leica was definitely better, but frankly, not by much.

The Zorki 5 was far from a cheap imitation. Like the Leica, it was made of solid metal, and had a nice and reassuring heft to it. The collapsible Industar-22 lens on this example looks nearly identical to the Leitz Elmar which coincidentally was on the Leica Ic I had. According to this article however, despite cosmetic similarities, the lens formula of the Industar-22 is not the same as the Elmar’s and more closely resembles that of a Tessar.

This particular Zorki 5 was painted a dark navy blue that when I first picked it up, I didn’t even notice. It wasn’t until seeing the camera in daylight that I ever saw that the body had been painted. Whoever did it, did it quite a long time ago as there were signs of the new paint wearing away on some of the edges. While a painted camera is hardly considered a way to make one more desirable, Soviet cameras have a long history of being painted in some very strange ways, but in this case, it was well done and I quite liked the color.

The most notable improvement of the Zorki 5, compared to the Zorki 2 series which it replaced, was the significantly redesigned top plate with wider rangefinder patch. All Zorkis from the very first model through the 4K have a rangefinder base of 38mm which matches that of the original Barnack Leica. Without going into too much detail, the wider the rangefinder base (meaning the distance between the two windows), the more accurate the rangefinder can be. Both the Zorki 5 and 6 have a wider base of 67mm which matches that of the FED 2, which should improve focus accuracy, especially up close.

This being the rather short lived first variant of the Zorki 5, the rangefinder window is rectangular, and the Zorki 5 logo is engraved into the metal and painted red. The later, and much more common Zorki 5 has a rounded rangefinder window, and instead of an engraved logo, there is a metal plate screwed into the body. For the completists, there are a very small number of “hybrid” models in which the rangefinder window is round, but there is still an engraved logo.

The top of the camera shows more improvements from the Zorki 2. From left to right there is a larger combined pop up rewind knob and film reminder disc. Although the rewind knob doesn’t have have a swing out lever like later cameras did, this is still significantly easier to use than the tiny ones on earlier models. Next to the disc is the accessory shoe, shutter speed selector, rewind release, and shutter advance lever. In the center of the wind lever are both the shutter release and exposure counter. The shutter release is threaded for a release cable, and the exposure counter does not automatically reset. A word about the shutter speed selector is that because this model lacks slow speeds, it is possible to change shutter speeds before or after cocking the shutter, although it’s probably still a good idea to stay in the habit of doing it after cocking the shutter, especially if you have other Soviet cameras in your collection.

There is one more feature on the top plate which isn’t immediately obvious the first time you use it, which is an adjustable diopter on the side of the rewind knob. The little raised tab next to the knob in the picture to the left is the diopter adjustment, and like the FED 2, makes using the camera much easier for people with prescription glasses.

The bottom of the camera features only the threaded 3/8″ tripod socket, and standard “Leica style” release latch. If you would like to use the Zorki 5 on a modern tripod with a 1/4″ post, you’ll need an adapter. To load film in the camera, you must remove the bottom plate by rotating the lock to the Open (откр) from the Closed (закр) position.

With the bottom removed, you have what looks to be a standard Barnack Leica film compartment. The first step in loading film into any bottom loading camera is to trim the film leader approximately 10cm in length, attach it to the take up spool, and insert both the take up spool and film cassette into the camera at the same time. Once both sides are in, you turn the shutter release twice to make sure the film is catching and then close the camera and get ready to shoot

The process is exactly the same as a bottom loading Leica, which I cover in my review for the Leica Ic. The image to the right shows the film compartments of both a Leica and the Zorki side by side.

The collapsible Industar-22 lens that came attached to this Zorki 5 is probably not original to the camera. According to all literature I’ve seen, the Industar-50 was the base lens on this model, but comparing the two lenses, they’re practically the same. Some say the 22 is an inferior lens to the 50, but I’ve also read that whatever difference there might be between the two, is within the sample variance of each lens. To put it simply, both the Industar-22 and 50 lenses adequately compare to a Leitz Elmar. If you are in the market for a period correct collapsible M39 lens for not a lot of money, you could do much worse.

A word about changing lenses on the Zorki 5. A number of Soviet websites claim that there is some design element unique to the Zorki 5 that requires you to have a lens mounted before firing the shutter. It is said that if you attempt to fire the shutter without a lens mounted, you can damage the rangefinder. I am not sure if this is true, but it seems to be such a common statement, I figure I’ll pass it on here as well. As this was not my camera, I did not attempt to see what might happen upon firing the shutter without a lens.

The viewfinder of the Zorki 5 is of average size. Smaller than the Zorki 4, but bigger than the FED 2. Although this particular camera could have benefited from a cleaning of the viewfinder, the square rangefinder patch is contrasty and easy to see. The adjustable diopter was a huge blessing on this camera, making up for it’s smaller size and allowing me to see the whole image while wearing prescription glasses. There are certainly larger and brighter examples out there, but considering this camera’s Barnack roots, this is a huge improvement.

Overall, there’s quite a lot to like about the Zorki 5. It’s hardly the first, second, or probably even third model that most people will think of when recommending a 35mm Soviet rangefinder, but maybe it should be. The feature set of the camera is competitive, it has a good viewfinder, a nice film advance lever, and it is compatible with nearly every Leica thread mount lens ever made, which means the images it is capable of can be quite outstanding.

My Results

For my first roll through the Zorki 5, I chose a roll of fresh Fuji 200 to take with me on a summer trip to the zoo. I loaded the camera like I would any bottom loader and made sure to follow the correct steps, but I kept encountering a problem where something was catching the film leader as I was inserting it.

I struggled to get that film into the camera and ended up crinkling the film leader pretty bad. Not wanting to continue cutting into an otherwise good roll of film, I tried it on a second one. I still struggled to get it smoothly into the camera, but once it was in there, it seemed to advance correctly, so I closed up the camera and took it out shooting.

After firing off no more than 2-3 exposures, I could feel something was wrong. There was little to no tension on the film lever as I was advancing it, as if the film wasn’t transporting. I fired off a few more shots just to be sure and I was pretty confident something was wrong. I opened the bottom of the camera and could see the film leader was not moving as I advanced the lever.

I tried one more time to attach the leader to the spool but could clearly see the perforations on the 35mm were being chewed up as if the sprockets were moving, but the film wasn’t. Frustrated, I put the camera aside and planned on coming back to it later.

Sadly, I held onto this Zorki for far too long and it came time to return it to it’s owner, without ever having a chance to properly shoot it. I never did discover why I had trouble with the film transport. Perhaps I wasn’t doing it correctly, or maybe there was just something wrong with this particular camera that required service. Both options are very likely. In any case, I am sorry to say that this review will have no samples of photos shot by me. In an effort to show you something, here is the Photo pool from a Flickr group dedicated to Zorki cameras. Since these are interchangeable lens cameras, its likely you’ll never see a difference in the images shot in a Zorki 5 versus any other Zorki.

My experience with this Zorki 5 was a bit of a bummer, but I can still walk away with a certain fondness to it. There are those who will scoff at my attempt to use this 60 year old Soviet camera and say “you should have used a Leica”, and to that I’ll say, show me a 60 year old Leica that doesn’t also need service. The Leica Ic I recently reviewed had a Swiss cheese shutter with light leaks galore, and neither the slowest of the fastest shutter speeds worked on that camera. Even the mighty Leica M3 I reviewed last year had an issue with the fastest speeds as well.

Yes, its true that most Soviet cameras were not built with the same tolerances and dedication to quality control as the Germans, but for what little shortcuts were done when producing these cameras, it is more than made up for in value. You shouldn’t expect Leica quality from a camera that costs significantly less than Leica. If given another Zorki 5 that was in better shape would I take a chance at it? Absolutely!

Additional Resources

http://sovietcams.com/index.php?-1778655067

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Zorki_5

http://ussrphoto.com/Wiki/default.asp?WikiCatID=70&ParentID=1&ContentID=237&Item=Zorki+5+Type+1

https://www.rangefinderforum.com/forums/showthread.php?t=30959

https://www.lomography.com/magazine/21829-zorki-5-a-russian-monster

You have evidenced the key reason why Zorki-5 was discontinued, it’s winding system was not reliable. Zorki-6 has no such issue.

So, did you ever find out what was wrong with the Zorki-5?

Both my son and I have one of these Zorki 5 cameras and the film transport mechanism is smooth and quiet on both of them. The only difference between the two is the design of the leatherette covering. I have to say that in my humble opinion the Zorki 4 (not the K) is a much better camera.

Another excellent review Mike. Keep them coming.

Having been inside a Zorki 5, a Zorki 4, AND a Zorki 4K… there’s no way I’d take a 4-series Zorki over the 5. The Zorki 5 is just much more robust internally (with one exception which I’ll get to in a sec).

With regards to film transport, the issue is usually one of user error; when inserting the film into the camera, you have to make sure the teeth on the film advance sprocket have entered the sprocket holes on the film. If you don’t, the camera will “wind on” as normal, but the film won’t actually advance. This is true of all bottom-loaders – Leica, Canon, Leotax, Nicca, early Zenits, etc. – and catches out all new users at least once.

The one design flaw of the Zorki 5 is what Mike mentioned above – it’s very true that you shouldn’t advance the shutter with the lens removed. If you remove the top of a Zorki 5, you can see the problem instantly: the rangefinder cam follower pivots very closely to the shutter mechanism, and if the lens is removed, the arm moves outwards so much that the other end of the cam follower can (and will) get tangled in the shutter mechanism.

I strongly suspect this (plus the general resistance to bottom-loading cameras by this point) is the main reason the Zorki 5 only lasted two years before being replaced by the Zorki 6, as the Zorki 6 moves the pivot for the rangefinder cam follower to the other side of the lens mount to get it away from the shutter mechanism. It’s a shame because the Zorki 5 is a damn fine camera; if I could only use one Soviet camera for the rest of my life, it’d be a Zorki 5. They’re solid and dependable things.