This is a Voigtländer Superb, a twin lens reflex camera made by Voigtländer AG Braunschweig between the years of 1933 and 1939. The Superb was Voigtländer’s first and what would end up being the company’s only true TLR camera they would ever make. It was designed to compete with the Franke & Heidecke Rolleiflex which was released in 1929. As they often did with their other cameras, the Superb took no design cues from it’s competition, offering features such as automatic parallax correction, horizontal film transport, and a reflex mirror for viewing shutter speeds, that no other company had. The Superb was a very well built camera and came with the company’s best lenses like the Heliar or the Skopar. Despite it’s quality craftsmanship and excellent optics, it couldn’t compete with the Rollei, and was discontinued shortly before WWII, never to be produced again.

Film Type: 120 Roll Film (twelve 6cm x 6cm exposures per roll)

Film Type: 120 Roll Film (twelve 6cm x 6cm exposures per roll)

Lens (taking): 7.5cm f/3.5 Voigtländer Anastigmat Skopar uncoated 4-elements

Lens (viewing): 7.5cm f/3.5 Voigtländer Anastigmat Helomar uncoated

Focus: 2.6 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coupled Reflex Waist Level Viewfinder

Shutter: Compur Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/250 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Weight: 903 grams

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/voigtlander_pdf/voigtlander_superb.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Voigtländer Superb tells you everything you need to know about it in it’s name. This camera was produced in 1933 and was meant to directly compete with the Rolleiflex. Although it compared favorably feature for feature, and even had a few things that the Rollei didn’t, it didn’t sell as well and was only produced for 6 years. It is a gorgeous camera that looks like nothing else ever made. This example with the Skopar lens produced outstanding shots on black and white and color film. The viewfinder is a bit dim, but is consistent with other cameras of the era, but overall, this was a really well made and fun to shoot camera that I think every collector should have in their collection. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 40% | |

| Bonus | +1 for overall coolness, one of the neatest cameras I’ve ever encountered, and yes, I know I already gave it a ‘3’ in Feel & Beauty, this is my site, so I can do whatever I want! | ||||||

| Final Score | 15.0 | ||||||

History

Voigtländer is the oldest name in photography, having existed as far back as 1756 in Vienna, Austria. I’ve covered these early days of the company’s history before, if you’d like to read more, but for this part of the story, we’ll start in the early 20th century around the time Voigtländer had made a serious push into producing their own cameras.

On January 10th, 1900, Voigtländer would hire a 20 year old mechanic named Reinhold Heidecke who worked in the company’s factories as a designer. Between the years of 1904 and 1905, he would temporarily step away from the company to serve in the German military. Upon his return to Voigtländer, he would be promoted to a production manager. Heidecke was an excellent designer, and in his new role he would help Voigtländer with many of their early folding camera designs.

In 1909, an intern named Paul Franke worked in sales for Voigtländer where he would start to develop connections within the German photo industry. Paul Franke was an excellent salesman and would quickly learn the business of exporting and in 1912 would leave the company to work for a rifle scope company called Géhard, likely in some type of sales role. A large number of Géhard’s sales went to other European countries and the United States, and with the start of the first World War in 1917, the company’s sales would come to a halt, causing the company to quickly go out of business, leaving Franke unemployed.

Shortly after, Paul Franke would form his own company called Franke & Co. whose products were mainly rifle scopes, microscopes, and binoculars. Franke’s skills in sales and connections within the German optics industry earned him contracts with the German military. With the war, demand increased to the point where Franke had to reconnect with his old company and start to offer products built by Voigtländer.

It was at this time when Paul Franke would meet Reinhold Heidecke and the two would form a friendship that would last decades. With Franke’s strong business mind and his contracts supplying the German military, and Heidecke’s previous military experience and eye for design, the two men started working on an idea they had for a new type of camera ideal for battlefield photography.

Until this time, if you wanted a portable camera suitable to be carried by a soldier, your only option was some kind of compact folding camera. In 1912, the Eastman Kodak Company would develop a compact camera called the Vest Pocket Kodak. These cameras were collapsible roll film cameras that used a leather or synthetic bellows system connected to a moving lens and shutter assembly. Although Kodak’s Vest Pocket design was very popular, many companies including Voigtländer copied it, creating their own versions of Vest Pocket cameras. This new style of camera became very popular during the war, and were given the nickname of the “soldier’s camera”.

Many vest pocket cameras were sold and used by participants on all sides of the war, but both Franke & Heidecke saw several flaws with the design. For one, the bellows were fragile and could not handle dirt or moisture well which would cause holes to form, thus rendering the camera useless. An often told story that Reinhold Heidecke once left a folding camera in his basement over night and rats had chewed through the bellows further confirmed this flaw. Furthermore, the design of the camera’s viewfinder required the photographer to either hold it at eye level, or at chest level, requiring the photographer to put himself into harms way if he wanted to photograph a battle.

In an effort to overcame all of these shortcomings, Reinhold Heidecke came up with the clever idea of a new solid bodied camera that used a reflex mirror which could work like a periscope to shoot photos. A soldier could use this camera in the trenches and hold the camera above his head and photograph something without ever having to stand up. The camera would have a large, life size viewfinder that would allow it to be used at an arms length, rather than eye level, further simplifying composition. Finally, the camera would be a solid body, and wouldn’t need bellows, meaning it was more rugged and able to handle the poor conditions of a battlefield.

Both Franke & Heidecke would attempt to convince the leadership at Voigtländer to build their new reflex camera, but for reasons I couldn’t uncover, they were unsuccessful. Voigtländer must have thought the new design to be too complicated, or perhaps they didn’t see the appeal of re-inventing photography in the middle of a war, especially when there was already demand for Vest Pocket cameras.

Unfazed by Voigtländer’s reluctance to produce the camera, in 1920, Paul Franke and Reinhold Heidecke would form their own company, simply called Franke & Heidecke. Although their purpose for starting a new company was to produce their new camera, working without the support of a major optics company, the men needed to build something that they were already familiar with that could be sold easily and help build capital in the company. For that, they chose a glass plate stereo camera which they would eventually call the Stereo Heidoscop. This was a design that Heidecke had a lot of experience with while working for Voigtländer, so they were able to put together their own design rather quickly.

Along with Paul Franke’s excellent sales and business skills, the new stereo camera sold very well. Demand for Franke & Heidecke’s stereo cameras helped grow the company quickly, and by 1923 required them to move to an all new 60,000 sq ft factory. That same year, a new roll film version of the Stereo Heidoscop that used 117 format rollfilm was introduced that was called the Rollfilm Heidoscop. This new camera had the nickname of “the Rollie”, a name which the company would eventually be named after.

In 1927, the time came for Reinhold Heidecke to finally build his new twin lens reflex camera, and a prototype of the new Rolleiflex was introduced. Over the course of the next year and a half, a total of 11 different prototypes were built, refining the design of the camera until it was ready for commercial production. A very small number of early cameras were built in 1928, but it is widely accepted that the first year of availability for the Rolleiflex was 1929.

Now, at this point, you’re probably thinking, “gee Mike, you sure are spending a lot of time talking about a camera that Voigtländer didn’t even make”, and you’d be right.

But you see, this is where I come back around. The Rolleiflex was an immediate success. It revolutionized professional photography and would become a world leader in photography for the next several decades. The Rolleiflex is one of those cameras like the original Kodak box camera or the Barnack Leica that defined the industry. Perhaps realizing their mistake in not accepting Paul Franke and Reinhold Heidecke’s idea back when they first proposed it, Voigtländer would eventually start work on their own twin lens reflex camera.

I could not find any information about the development of the Superb. Things like who designed it, or how long it was in production are a mystery, but a few conclusions can be drawn based on the final product.

For one, the Superb looked nothing like the Rolleiflex. One of the most striking features of the design are the two humps on the sides of the camera which are necessary to accommodate the supply and take up spools of the camera, as unlike mos other TLRs, film transport is horizontal. (Edit: After publishing this article, astute reader Mike Novak corrected me in saying the Zeiss-Ikon “coffee can” Ikoflex also had a horizontal film transport.) With any kind of camera that shoots square images, the orientation of the film makes little difference, but the more common vertical transport easily hides the film compartments, but not here. Why did Voigtländer do it this way? Was it their desire to just be different, or was there a practical reason? Who knows!

Upon it’s release in 1933, the Voigtländer Superb was a compelling alternative to the Rolleiflex. Priced approximately 25% cheaper, the 1935 Central Camera catalog lists the Superb with f/3.5 Skopar lens at $79.50, compared to $112 for a Rolleiflex with f/3.5 Tessar. Later catalogs price the Superb at $69.50.

Feature for feature, the two cameras were very comparable. Both would have had a Compur leaf shutter with speeds from 1 – 1/500, both came with very good 4-element lenses, and had ground glass viewfinders with a sports finder and spirit level. Although both had an automatic exposure counter and lacked the feature which would stop the film advance at the next exposure (the Superb would never get this feature and the Rollei wouldn’t have it until the Automat 6×6 in 1937), the Rolleiflex had a faster crank wind film advance as opposed to the small lever on the Superb which takes several movements to advance one exposure. The Superb bested the Rollei in a couple of ways though, the most significant was it’s support for parallax correction.

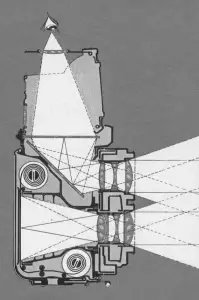

Parallax is the error encountered at close focus distances due to the vertical distance between the viewing lens (the one you look through) and the taking lens (the one that exposes the film). At distances of 6 feet to infinity, parallax error is effectively non-existent, but the closer you get to the camera’s minimum focus, the greater it gets. Franke & Heidecke and other TLR makers would address the parallax problem with moving frame lines in the viewfinder, various accessories like special prism filters, or devices that would attach to the bottom of the camera and would raise or lower the camera during composition.

Voigtländer addressed it with a very effective, albeit complicated method in which the entire viewfinder, glass, reflex mirror, and taking lens are in one self contained module that can swivel up and down depending on the chosen focus on the camera. At distances nearing infinity, the taking and viewing lenses are parallel, but as you focus closer, the entire viewfinder assembly swivels down, showing an accurate representation of the close focus image in the viewfinder. This system in the Superb worked extremely well, but likely was deemed too complicated as I’m not aware of any other TLR cameras ever made that had a similar system.

The Superb was only in production for about 6 years before being discontinued around the start of World War II. During that time, only one upgrade was offered, which was the inclusion of a 5-element Voigtländer Heliar lens. Franke & Heidecke would eventually follow suit, offering an upgraded Biometar lens, but not until 1952.

In 1956, to coincide with Voigtländer’s 200th anniversary, the company revealed their plans for some new cameras they were working on, one of which was an all new Superb model. It was an elegantly designed camera that appeared to have many of the modern conveniences that TLR users had come to expect by the 1950s, but sadly, never made it into production. A non-functioning prototype Superb was offered at the WestLicht Photographica Auction in May of 2006, but did not sell.

Today, the Voigtländer Superb is a highly desirable camera by collectors and users alike. It’s unique looks, quirky functions, and excellent reputation make this a must have. Models with the Heliar lens are considerably more rare, fetching well over $1000 in decent condition. Deals can be had on the Skopar models if you are patient enough.

My Thoughts

This Superb came to me at the exact same time I received a Rolleiflex Automat K4A, and while the prospect of adding a Rolleiflex to one’s collection should give any collector pause, guess which one I was more eager to shoot?

The Voigtländer Superb is unlike any other TLR camera ever made. Not only does it look different, it also works different, having features that the Rolleiflex never did. Although no one can deny the success of Franke & Heidecke’s signature series of cameras, one drawback to the success of the Rollei line is that so many others copied them. If you’ve never used a Rolleiflex before, you can gain a nearly identical experience simply by picking up any number of clones by Yashica, Minolta, Walz, and a myriad of other “pseudo-Rollei” cameras made during the middle of the 20th century. While I won’t argue whether the quality of these copies lives up to the original, the user experience does.

When you have the opportunity to shoot something copied time and time again, versus something completely different, I went with the different one, and I’d be willing to bet you would too. I mean, just look at it!

Take a moment and look through the gallery below admiring the little details on this camera such as the engraved leaf pattern behind the SUPERB logo, the vibrant blue and yellow enamel behind the script “V” on the top lid, the always beautiful embossed Voigtländer logo above the exposure counter, and the nickel plated rings around the taking and viewing lenses and aperture selector.

Beauty aside, the camera had some functional highlights as well. Perhaps the most striking is the backwards script around the Compur shutter ring. Many people who see this don’t understand that the reason for this was to accommodate a tiny prism that when viewed with the camera at waist level would allow the photographer to see the selected shutter speed. The prism viewer has a hinge that allows it to swing away from the camera for easier cleaning, should it become dirty.

In the section above, I talk about the Superb’s unique method for handling parallax error in which the entire viewing lens, reflex mirror, and viewfinder swivel down at close focus. In the third image below, the camera is set to minimum focus and you can see how it is angled downward, towards the taking lens. Another easily missed detail, is that in the upper right corner of the viewfinder is a small spirit level which helps the photographer keep the camera level while composing.

The most obvious characteristic of the exterior of the camera are the two humps on either side of the camera that cover the take up and supply spools inside the film compartment. Unlike pretty much every other TLR which traverses the film vertically, the Superb is horizontal (the Zeiss-Ikon “coffee can” Ikoflex is also horizontal). A theory I read online is that perhaps Franke & Heidecke had a patent for their horizontal film transport, but there were other pre-war German and Japanese TLRs like the Eho Altissa Altiflex and the original Minoltaflex, both of which worked like the Rolleiflex.

On the camera’s left side is the film advance lever which is not coupled to the shutter and will not stop once you reach the next exposure. For that, you have to pay attention to the exposure counter on the back. The counter relies on a feeler wheel within the film compartment that rotates as the film passes over it. On this Superb, the counter wasn’t functioning correctly, so I had to measure how many movements of the film advance lever were required to properly advance the film. For exposures 1-4, you advance the lever six times, for exposures 5-8 advance it five times, and for 9-12 four. The reason for the different amounts is that as the film spools onto the take up spool, it gets thicker, causing more film to pass over the film gate later in the roll.

The bottom of the camera has two feet, and a raised tripod socket that keeps the main body from touching whatever you have the camera set on. While this looks neat, it has the side effect of de-stabilizing the camera when mounted to a tripod. I would be very careful not to bump the camera while mounted to a tripod as it could very easily damage the socket.

Loading film into the camera requires that you release the latch on the camera’s left side which not only allows the left hinged side to swing open, but the other right hinged side as well, revealing a film compartment completely exposed on three sides. I had concerns about light leaks with a design like this and although there was evidence of a light leak in one of my exposures, it wasn’t there on any of the others, so at the very least, when this camera was new, it probably did a fine job.

A new spool of film goes on the camera’s right side, as film travels from right to left. The backing paper goes over the two rollers at each corner of the film compartment. I mention above that the exposure counter relies on a feeler wheel within the film compartment which you can see in the previous image to near the upper right corner of the film gate.

Peering through the viewfinder is one of the few unpleasant aspects of using the camera as the view is quite dark. There is a sports finder and a magnifying glass, but these really don’t help much for overall composition. A dark viewfinder was a sign of the times however, and not anything wrong with the camera. A look through the viewfinder of my 1930s Rolleiflex Old Standard is nearly the same. These TLRs predated the use of laser cut focusing screens with Fresnel patterns to improve brightness. It’s fine in well lit outdoor scenes, but in shade or indoors, it can be quite difficult to compose your image.

All of your primary shutter controls including shutter speeds, f/stops, and focus are on the front of the camera. The aperture is controlled via a dedicated wheel above and to the left of the shutter, speeds are controlled via the large metal ring around the shutter, and focus is controlled via a sliding lever near the bottom of the camera. Cocking the shutter is not coupled to any other part of the camera, which means you have to do it in a separate step prior to firing the shutter. This is consistent with the earliest Rolleiflexes, but is a bit of a downer when compared to later TLRs. The cocking lever is near the 3 o’clock position of the shutter, and the shutter release is near the 10 o’clock position. Although it’s not obvious, the Superb does have an approximate 12 second self-timer, which is activated using the cocking lever. Under normal use the cocking lever hits a little safety catch when it is fully cocked, but you can move the safety catch out of the way using a small slider on the side of the shutter. This allows the cocking lever to go beyond it’s normal position, which activates the self-timer.

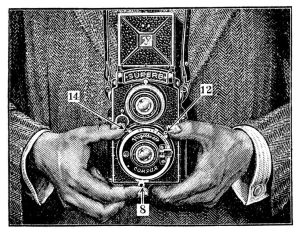

The position of the focusing lever below the lens is actually quite a convenient location, which was further explored by Chiyoda Kogaku with the Minolta Autocord. The Rolleiflex has a knob on the camera’s left side for focus, which requires use of your left hand. But while your left hand is changing focus, your right hand naturally has to support the camera, restricting it’s ability to fire the shutter. With the Superb, your left hand can both cock the shutter and focus the lens without having to move, freeing your right hand to remain on the shutter release until it is needed. The Superb’s user manual suggests holding the camera like the image to the left with the focus lever (8) controlled by the index finger on either hand, the left thumb on the cocking lever (12), and the right thumb on the shutter release (14). I found that holding the camera in this manner was comfortable and felt very natural.

The Superb was a joy to use, and although quite heavy at 903 grams, it wasn’t a problem for waist level shots. I would definitely recommend some kind of neck strap if you plan on walking around shooting this camera. When cameras like this and the Rolleiflex first debuted, they were state of the art devices and were considerably smaller than the large single and twin lens reflex “falling plate” cameras that preceded them. For something that could hang from your neck all day and capture as many as 12 (8 in the original Rolleiflex) shots without having to reload the camera was truly a game changer at the time.

Repairs

This Voigtländer Superb came to me in mostly good condition with only two issues. The first was the broken exposure counter which I talked about earlier, but the other was a very dark and dirty viewfinder. It is not unusual to get a 1930s TLR with a dark viewing screen. For one, the ground glass focusing screens used back then were inferior to plastic screens with Fresnel patterns that would become in later decades, but also the perils of time will cause dirt to get in there and the mirror to desilver, which is the flaking off of the reflective material.

With most TLRs, cleaning or replacing the viewing screen and mirror is as simple as removing a couple of screws and removing the hood. The Superb has a much more complicated design which when I was preparing to shoot this camera, I couldn’t figure out. After publishing this review, I was sent the photo to the right by Rick Oleson which shows the screws needed to remove the entire viewfinder assembly. There are a total of 7 screws that need to be removed, and they’re all hidden under leather.

I never attempted this repair on my camera, but maybe one day I will, and if I do, I’ll be sure to update this review.

My Results

For my first roll through the Superb, I thought I would pair up the pre-war uncoated Skopar lens with some black and white film, so I chose a fresh roll of Fomapan 100 that I had recently picked up at Central Camera in Chicago. After all, I was headed to Chicago for a day of walking around the loop, so why not use the film I had purchased in the area.

I will admit, having to count how many frames I had shot and remember to advance the film the correct number of times depending on where I was in the roll of film was a bit of a hassle. Had this Superb had a working exposure counter, the experience would have been a bit less stressful, but any thought of negativity I had while using the camera completely vanished after developing the first roll.

Focus and exposure on this 85 year old camera was spot on. The uncoated Skopar lens delivered consistently sharp images across the frame with only the slightest amount of vignetting, giving a contrasty and glorious roll of images. Although a higher spec 5-element Heliar was available in the Superb, I can’t see any reason why anyone would pay extra for that lens as these images with the Skopar were spectacular.

I was so impressed, I wanted to see what color film would look like, but as time was running short to get shots in the camera, I took a half exposed roll of Kodak Portra 160 out of another camera and transplanted it into the Superb and finished the roll. Above are 8 shots from that first roll of Fomapan, and 4 from the Portra.

Colors were understandably muted from the lens, but were consistent with how Portra 160 looks in other cameras. The image of the flowers in the window is a little hazy, but that is because it was shot inside of a mausoleum through a dirty glass door.

I have a couple of Rolleiflexes and I will eventually get around to reviewing them here. They’re great cameras and make great images, but when you pick up a Rollei you expect that. There’s no surprise when you shoot a camera that literally everyone else copied. I have the same problem with early Leicas. Yeah, they’re great, but everyone already knows that.

Cameras like the Voigtländer Superb aren’t nearly as talked about and while you generally should expect anything made by Voigtländer to be good, the question becomes “how” good, and what is it like to shoot. I can now answer those two questions with one single word:

Superb!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Superb

https://photothinking.com/2024-03-25-voigtlander-superb-just-superb/

https://www.dancuny.com/camera-collecting-blog/2020/10/26/voigtlander-superb

https://www.flickr.com/groups/1710810@N24/discuss/72157629933237230/

Excellent revue and wonderful images, thank you Mike.

Thanks Mike… Very timely review, because after months of looking, I finally found a Superb in great working order. It just arrived from Northern Europe and I can’t wait to put a roll through it!

I am jealous. I want one too 🙂

Great article. Thank you

Hi fantastic information, my Auntie has a superb given by her uncle, it has been well looked after and still in original case! Do you have any idea of value? Thanks

Hi Jane, thanks for the compliments. The value of these varies wildly depending on operating condition and which lens it has. I can tell you, I sold the exact camera in this article for $150, but the frame counter wasn’t working correctly. It has the Skopar lens which is a good lens, but not worth as much as the Heliar. Superbs with the Heliar lens go for considerably more, in the $750 – $1000 range. Is yours for sale?

Great post and I am glad you like teh Superb. I have one too and since getting in CLA’d everything works wonderfully apart from an annoying light leak – putting it in a case will (I suspect) help to resolve this in the meantime I am trying to narrow down the source.

One thing about why the technical design is so different – I understand that Patents were very strictly policed and adhered to in Germany around that time so in order to build a camera similar to the Rollei, Voigtländer had to re-invent a lot of things. The result is a unique and in my opinion wonderful camera that I feel lucky to own.

Your light leak is likely from one of the hinged doors. A case is a good idea, but if you want some additional security, you can get some adhesive backed black felt from an arts and crafts store and cut it into thin trips and line the inside edges of the doors. I had to do that to my Minolta Autocord where no matter what I did, I had minor light leaks from the door.

Mike, the hinged doors are made from pressed sheet metal and surprisingly thin, if you recall. Looking at the right hand hinged door on my Superb, it is slightly dished at the point it meets the left door and can only rely on the pressure of the left door overlapping it and the strong locking hinge to flatten it. If there is anything that could rob the camera of its “Superb” name it would be this design weakness.

I didn’t use mine enough, a couple of test rolls, to discover if this was an actual issue or not.

Hi Mike,

is it possible to tell me the exact exposure format of your Superb? Unfortunately only film strip height is standardized. Hasselbald exposures are 56x56mm, two eyed Rolleiflex 57x57mm etc.

I’m developing film strip masks for Nikon Coolscan 8000/9000 scanners and a good fitting is important for a good scan.

Thanks in advance 😉

Mike, as with some other posters here, I have a Superb and which was one of my first acquisitions for my nascent camera collection in the late 1970’s. The lens’ serial numbers, 896964 Skopar and 903326 Helomar, would place it earlier than yours, which I do see you have since sold. There is one significant difference, though, between the bodies. Mine has a second red “peep” window in the middle of the camera back, on the same level as the locking catch. The instruction manual I have makes no reference to this, only the window on the right-hand side. Also, the manual refers to the Voigtlander film as 2 1/4 x 3 1/4 format, i.e. 8-on 120.

Now I suspect that Voigtlander decided to include this second window to make loading 120 film that included backing paper numbered for 12-on 120 film that was available from other film suppliers. This would also have the added advantage, definitely so in your particular experience, of not having to rely on the dodgy film counter.* But this seems odd, especially if my Superb is an earlier release than the one you had. Why subsequently remove this clearly obvious benefit?

* One way round this with Superbs that lack the second peep window, is to follow the instruction in the manual when using the camera in low light levels that make it impossible to actually see the frame number. This can, of course, equally apply in daylight. Voigtlander suggest 7 actions of the wind lever per shot. But they do say only 11 exposures can be made and not 12.

As for the dull viewfinder screen this can be exacerbated by dust on the reflex mirror, or more worryingly, de-silvering of the mirror itself. I found this out to my despair when I thought I was simply removing dust. The silvering simply came away with the dust. Aaargh! With a little ingenuity, I effected a repair which works surprisingly well in actual practise. I used the reflex mirror from a junk and defunct 35mm camera and glued this in place in the best position on the original mirror that I determined from trial and error. This threw out of synch the focused image in the viewfinder, of course, but this is easily corrected by simply unscrewing finder lens and re-setting focus by sight. Once I was satisfied that the finder focus was as close to the taking lens as I could get it, I applied a little super glue to fix it in place.

Since trying to view the whole screen on this camera is a trial to say the least, getting the majority in view and clearly in focus, it doesn’t matter what is not visible in the extreme edges or corners.

The superb is full of nobility. I think the superb shoulder above the rest of all the TLR of its time.

Excelente publicacion, un informe muy detallado de la Voigtlander Superb.

I picked up a Superb and had it overhauled by Dan Daniel in Vermont. It’s a fantastic camera, but I haven’t shot much since COVID struck. Tim to load some fresh film and give it a go!

Good to know of a resource for overhauling these cameras! You have no excuse to not shoot it now! 🙂

Thank you for the very informative and intersting article with beautiful and tasty photos

taken by Superb! My main camera is also a Superb with heliar.

I have owned Rolleiflex A, E, F and two Rolleicords.

They are great cameras but I sold them all but will never for Superb.

According to Mr. Hayata, a famous classic camera repairer and dealer in Japan,

Voightlander had to take such a odd mechanisms in Superb to avoid violating more than 240 patents

Rolleiflex was holding.

After Germany lost WWII, Rolleiflex had to give up all the patents then many copies emerged amid the confusion.

I’m using lids of 35mm film case as lens caps that fit perfectly to both taking and viewing lenses,

and sliced the case with foam pad placed inside to make a lens hood which falls off occasionally 🙂