One of the thrills of shooting old cameras is stepping back in time and experiencing what a photographer likely experienced years ago before the widespread use of plastics, LCD screens, and microprocessors. Cameras were made of metal and glass, and used springs, gears, and levers to accomplish the same task of capturing a photograph, just like today’s advanced mirrorless and DSLR cameras.

Yet, for all of the fun and interesting characteristics that many old cameras share, sometimes there are things that just aren’t quite so memorable. If you’re a frequent reader of my site, you’ll hear me regularly complain about a feature called the Light Value Scale, or LVS for short.

Credited to F. Deckel, creator of the Compur leaf shutter, the LVS system first debuted in the Synchro-Compur shutter at the 1954 Photokina. The first appearance of the LVS system was on the AGFA Super Solinette and it’s American cousin, the ANSCO Super Regent, both from 1955.

Now, before I continue, I must clarify that I completely understand why the LVS was created. In fact, when it first debuted, it was quite an exciting new feature. Although still entirely mechanical, LVS was the first major step towards automatic exposure.

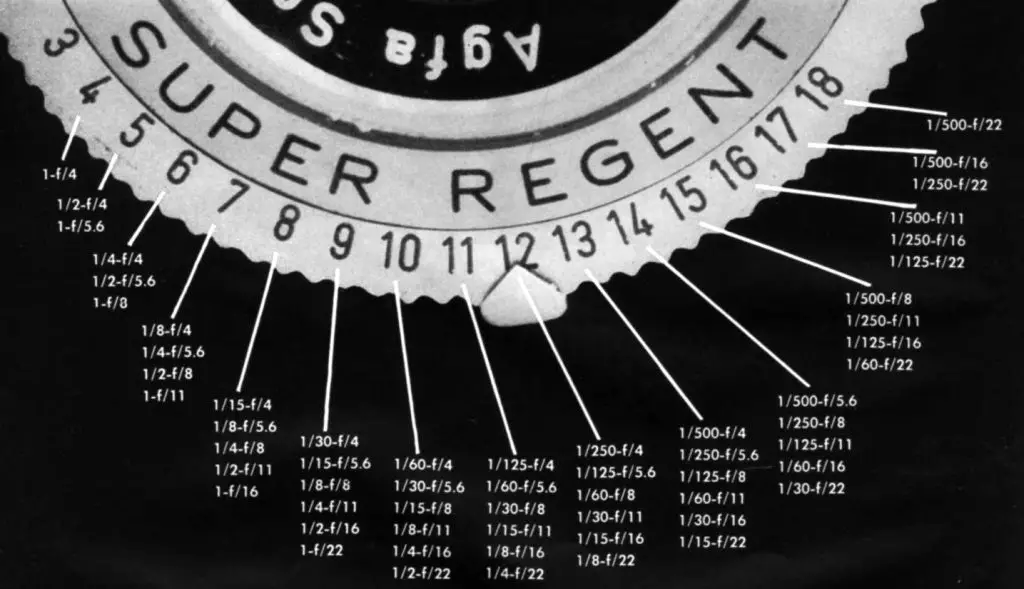

In a nutshell, how it worked was by using an established set of numbers (usually from 2-18) that were universal between camera brands and external light meters. It wouldn’t matter what brand camera or meter you were using, you would just set your chosen film speed on the meter, point it at a light source, and whatever light value number it gave you, you would set your camera to that same number and that would get you correct exposure. For the beginner who struggled to understand shutter speeds and f/stops, it was a great idea and worked well.

Cameras with LVS were primarily made between the mid to late 1950s and mostly had disappeared by the early 1960s. Advancements like fully coupled light meters and automatic exposure rendered them obsolete, so while the system wasn’t around for long, a huge number of cameras had them. Nearly every German or Japanese rangefinder, TLR, and leaf shutter SLR came with the LVS system during this point.

The biggest flaw in the LVS for me, is in the execution of how it coupled shutter speeds and f/stops together. Many German cameras like the Kodak Retina series and the Voigtländer Vitessa L used a small lever that would lock into position semi-permanently linking the shutter speeds and f/stops together. So for example, if a LV of 12 was needed, the camera would predetermine which shutter speeds and f/stops you could use. If you wanted to increase or decrease the shutter speed, the f/stop value would always change in the opposite direction to compensate. This is fine if you want to make quick adjustments for depth of field, or to freeze a moving object, but when the lighting situation changed, for example stepping into shade, or under cloud cover, you would need to manually change the LV number first, which on both the Retina and Vitessa were near in a cramped location near the bottom of the shutter. This would prove to be a problem if you needed to adjust shutter speed to a number beyond what the camera was physically capable of, given a set LV number.

Most Japanese companies like Yashica and Fujica, employed a similar system, but would allow you to override the chosen LV number by simply turning the shutter speed or f/stop setting to whatever value you wanted to override it to. The Germans seemed to be more adamant that available shutter speeds and f/stops followed the set LV number with no compromise, whereas the Japanese felt the photographer should be able to easily override it if they so wished.

The article below is from the July 1957 issue of Modern Photography and came right at the peak of popularity for the LVS. It explains much of the same info as I summarized above but goes a little more into the history and why it was implemented. It explains some of the history, along with a full chart of every possible shutter and f/stop combination available on most cameras for each LV number 2 – 18.

For as much grief as I give the LVS, it did have one pretty significant side benefit, which was that prior to it’s existence, there was not set standard for which shutter speeds should be on a camera. Speeds of 1/10, 1/75, and 1/100 were common on many leaf and focal plane shutter cameras prior to the mid 1950s. Since LVS requires that each speed be mathematically double that of the previous setting, a modern standard of 2. 4. 6. 15, 30, 60, 125, 250, 500, and 1000 became the norm on nearly every camera, regardless if it had LVS or not.

What I find the most interesting about the article below is the universal praise for it. It would seem that the target customer for cameras with LVS would never have a need to override it’s settings. The only mention of a Japanese maker is the additive LVS system on the Minolta Autocord. I wonder if people simply had different expectations back then than we do today and having to reset the LVS each time your lighting changed was less of an issue.

All scans used with permission by Marc Bergman, 2018.

One of my favourite cameras is my Minolta SRT 101 the match needle meter effectively shows the LV and the required combination of aperture and shutter speed lines a target up with the needle. No electronics in sight a system of bits of string and pulleys does all the calculating.

Wow. I did not know printing can be done at such tiny font size. I about went blind trying to focus on such tiny letters. Excellent article. If possible, enlarge the font a bit.

Hi Dean, glad you enjoyed the article, but every Kepplers Vault article has the images scanned in at 3000 dpi. Each page of the article can be enlargened in your browser by clicking on the page to more easily see the text!

I think the problem may lie more in the implementation of the system in the camera. I have little experience, but in my Ricoh Caddy it is super simple and super fast. A single turn to change the LVS value, either with speed or with the aperture, or to obtain an equivalent LVS combination.

It’s definitely implementation. I’ve used probably 30 or so cameras with LVS, and I can tell you that it varies greatly. Some camera companies did it in a way that’s easy to override with the camera to your eye, and others, you feel like you have to get into an argument with the camera each time your lighting changes and you want to change shutter speed or aperture, but not both.