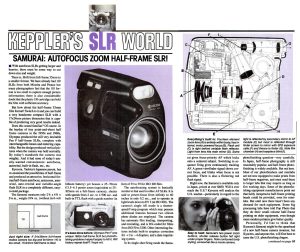

This is a Yashica Samurai x3.0, a half frame 35mm SLR made by Kyocera of Japan starting in 1988. The Samurai has a unique feature set, being one of the only vertically traveling half frame 35mm SLRs. It was also one of the first of a new genre of “bridge cameras” with a shape that resembled a video camcorder. Meant to be held and shot single handed, Samurai models were made for left and right handed people. The model name X3.0 signifies it’s 3x optical zoom from 25-75mm, but there was also an X4.0 model that went from 25-100mm. In 1988, the Samurai won the Japanese Camera Grand Prix award for it’s design. The Samurai can be found both using the Yashica and Kyocera branding, likely due to the market it was sold in. Although available in the United States, it was much more popular in Japan.

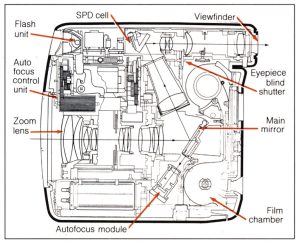

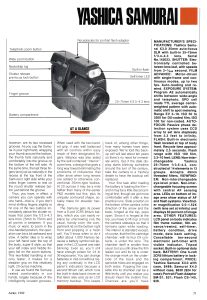

Film Type: Half-Frame 135 (35mm)

Lens: 25-75mm (35-105mm equivalent at full frame) f/3.5-4.3 Yashica zoom coated 14-elements

Focus: Fully Automatic 3.3 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Fixed SLR Pentaprism

Shutter: Electronic Leaf

Speeds: 2 – 1/500 seconds stepless

Exposure Meter: Two Segment Silicon Photo Diode with Full Programmed AE

Battery: 6v Lithium 2CR5 and non removable internal memory backup battery

Flash Mount: Built in flash with TTL metering and 2.5 second recycle time

Weight: 607 grams

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/yashica_pdf/yashica_samurai.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Kyocera/Samurai X3.0 is a very interesting camera with a unique upright camcorder design which could be operated single handed. It was a half frame 35mm SLR with a vertically traveling film compartment, which meant the default orientation of the viewfinder was in landscape, rather than portrait model like in most other half frame 35mm cameras. It’s unique looks and feature set attracted customers in Japan and the United States like. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0% | |

| Bonus | +1 for an innovative design and a unique feature set, not duplicated by many other cameras ever made | ||||||

| Final Score | 8.0 | ||||||

History

The camera being reviewed here has the name “Yashica” silkscreened onto it’s plastic shell, but by 1988 when it was released, the company once known as Yashica who made a long running series of medium format twin lens reflex and quality 35mm rangefinder cameras was no more. The Yashica name on this camera is merely a trademark used by a company called the Kyocera Corporation after it’s acquisition of Yashica Co. LTD in 1982.

The camera being reviewed here has the name “Yashica” silkscreened onto it’s plastic shell, but by 1988 when it was released, the company once known as Yashica who made a long running series of medium format twin lens reflex and quality 35mm rangefinder cameras was no more. The Yashica name on this camera is merely a trademark used by a company called the Kyocera Corporation after it’s acquisition of Yashica Co. LTD in 1982.

Originally formed as a ceramics company called Kyoto Ceramic Co. Ltd., Kyoto was a publicly traded Japanese company who pioneered the use of ceramics in early integrated circuits used in radios and other devices. Their first product was a type of ceramic insulator used in Cathode Ray Tubes used in televisions. In the 1960s, Kyoto expanded beyond simple ceramics to more advanced semiconductors used in early computers and other electronic devices.

In the 70s, their product portfolios continued to grow both within and outside of the electronics industry. Kyoto made products were used in as far reaching products such as solar panels to kitchen knives to lab grown gemstones. An investment in 1979 into a major radio communications company called Cybernet Electronics Corporation positioned them as a world wide leader in both semiconductor and electronic industries.

In 1982, Kyoto would fully acquire Cybernet Electronics, along with several other companies including one called Kagoshima Electronics Company, and in October 1982 would change it’s name to Kyocera, the name it still uses today. At the time, Kyocera was one of the largest Japanese electronics companies with several offices in Japan and some in the United States.

In an effort to gain some influence in the optics industry, in October 1983, Kyocera would acquire Yashica Co. LTD who at the time was a struggling company. With their ownership of the Contax name and lens system, Kyocera thought they could revive Yashica into a prominent Japanese camera company.

Kyocera’s first cameras were evolutionary continuations of models like the Yashica FX-3 and Contax 159MM SLRs, but would soon branch off into other designs. It is unclear today what Kyocera’s actual plan was for Yashica when they acquired them as for the first couple of years, they didn’t show any signs of any type of new revolutionary model. Yashica branded cameras continued to sell in low numbers as inexpensive, entry level models. No effort was made to compete in the advanced amateur or professional markets.

Kyocera’s first success with an all new camera design came in 1988 with their new 35mm half frame Samurai SLR. Half frame cameras had enjoyed good success in Japan since the release of the Olympus Pen in 1959. Shooting images that were half of a normal 35mm sized image meant that you could get twice as many exposures per roll. The format wasn’t as widely accepted in the United States however, as companies like Kodak made it difficult to accommodate the format in their professional lab developing machines, often charging a premium to get half frame film developed and printed.

The Samurai had a unique shape, resembling a video camcorder and could be used single handed. It was the first generation of what was then called a “bridge camera” in which the traditional shape and design of a camera was disregarded, replaced by all new, purpose built models that could “bridge” the gap between a cheap point and shoot and an advanced SLR. Other bridge cameras of the era were the Chinon Genesis, Ricoh Mirai, and Olympus Infinity Super Zoom 300.

Although the majority of Samurais were designed to be used in the user’s right hand, there were a small number of left handed models, indicated by the letter “L” in the model name, that reversed the entire shape of the body for use in a photographer’s left hand. These left handed Samurais are very rare today, and in my research for this article, I could only find a couple small, low resolution images of one. In addition to left and right handed versions, the Samurai came with a variety of accent colors including red and teal. There was even a transparent Samurai created, probably as a demonstration model, but I cannot be certain.

Reaction to the Samurai was quite positive, both in Japan and the United States. The Samurai was an instant hit in Japan, selling as many as 60,000 copies in it’s first 3 months on the market. It also won the Japan Camera Grand Prix camera of the year award for 1988. The Camera Grand Prix is an award given out by the Camera Journal Press Club of Japan, a group of representatives from magazines and websites in the industry. The award was first given out in 1983 to the Nikon FA, and as recently as 2018 was awarded to the Sony alpha 9 digital mirrorless camera. To commemorate the win, Kyocera released a Grand Prix special edition model with gold accents instead of the usual black, red, or teal.

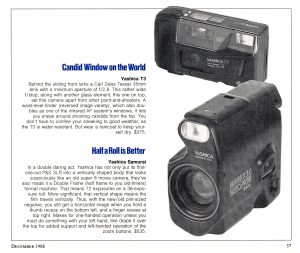

We know the Kyocera/Yashica Samurai was released in Japan in late 1987, but it would take almost a year for it to be released in the United States. Two articles I’ve found online, the first in the January 1988 issue of Popular Photography, and the second in the March 1988 issue of Popular Mechanics, both mention the camera’s availability in Japan, but an uncertain release date in the US. As for a price, the Pop Photo article says that the price in Japan is $440, so a US equivalent price might be around $350, and the Pop Mechanics article merely says the Japanese price is under $500.

The delay in releasing this camera in the United States was likely due to resistance from Kodak and other photo finishers who did not easily accommodate developing and printing of half frame images. In the mid 20th century when half frame 35mm cameras saw increased popularity in Japan and in Europe, a large number of American photographers shot on slide film, which could not be easily mounted into smaller half frame holders.

Even for those shooting color or black and white negative film, the general perception in the United States was that half frame cameras were inferior and not worth the additional challenges of getting the film developed. As a result most attempts at releasing half frame models like the Olympus Pen series only saw lukewarm sales here.

Yashica was persistent however, and thought that with the new design of the Samurai and it’s horizontally oriented viewfinder (courtesy of the vertically traveling film), along with a sharp and flexible zoom lens, and Single Lens Reflex design, that the camera would be accepted here.

Upon it’s release in late 1988/early 1989 (I still could never find a definitive release date), the camera was highly anticipated. In their April 1989 issue, Modern Photography saw it fit to dedicate 8 pages to a full test of the Samurai and all of it’s functions. You can read the article in it’s entirety below by clicking on the thumbnails to get to the gallery and viewing the full size scans of each page.

I could never find any official advertisements from Kyocera or Yashica regarding a retail price. Modern Photography’s 8 page article above lists the price of the X3.0 with case as $488.

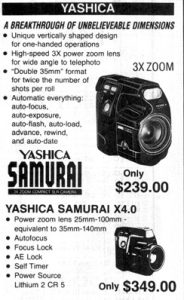

The ad on the left from a 1989 catalog for Smile Camera in New York City lists the price at a reasonable $239.00. Contradicting the other two is the short blurb on the right, from the December 1988 issue of Modern Photography which lists a retail price of $535 for the Samurai X3.0. When adjusted for inflation, these prices are comparable to $500 and $1125 today. I think an inflation adjusted price of $500 is a much more realistic selling price for a camera like this.

Regardless of the price that the camera sold for in the United States, we know it definitely was sold here. Whether it was a smashing success or not, it did sell well enough for additional models to be sold here. A higher end model with a 4x zoom called the Samurai X4.0 was offered around the same time as the X3.0, and then in the early 1990s, a simpler model called the Samurai Z eventually appeared on store shelves.

In 1998 Kyocera/Yashica would reuse the Samurai name on an APS viewfinder (not an SLR) film camera called the Samurai 4000iX. An inexpensive and cheaply built camera, the 4000iX only shared the original models upright form factor and half frame size. There was also an early digital camera using the Samurai name, but frankly, I don’t feel like looking up any information about it.

Today, the Samurai family of 35mm half frame cameras are quite popular among collectors. The camera’s curious shape and the fact that it is one of a very few number of half frame SLRs ever made, mean it has appeal for collectors and users alike. At a time when many Japanese companies were pioneering the concept of a bridge camera with innovative, but often terrible designs, the Samurai remains a highlight of a new era of film cameras, and one that still appeals to people today.

My Thoughts

The Yashica Samurai is one of the few cameras ever made that truly is in a class of it’s own. Sure, there were other easy to use “bridge” cameras that offered professional-like features in a simple, but transitional form factor, but none that I know of that have this combination of camcorder design with a vertically traveling half frame format with an SLR viewfinder.

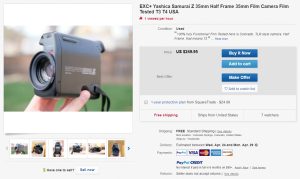

The first time I saw a Samurai, I knew I had to have one. The problem was finding one in my price range. These cameras did not sell well in the US, so the available selection of them today is quite thin. Of the ones that are for sale, they all seem to fall into one of two categories, broke and expensive. For the broke ones, this camera is from an early era of electronic cameras that have not aged well. I won’t fault Kyocera for not making a camera with great reliability 30 years after it’s release, but of the ones for sale, Samurais seem to be unusually susceptible to lens fungus and haze. Strangely, a large number of them being offered by Japanese sellers have hazy lenses which seems odd for a camera from the late 1980s.

Of the ones that are in good working condition, the Japanese sellers offering them are well aware of their popularity and are priced accordingly. We’re not talking Leica or Rolleiflex expensive, but for what amounts to not much more than an “electronic curiosity”, spending three figures on the total purchase price for one carries quite a bit of risk.

When it arrived, I was pleased that the camera was in great working condition and had a clear lens and viewfinder, showing no signs of haze or fungus. All it needed was a 2CR5 Lithium battery, which I already had, so I loaded it in and took it out shooting.

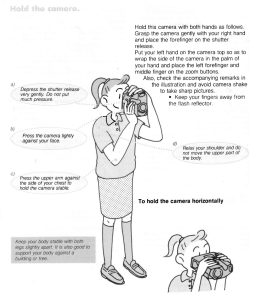

The best starting point for a Samurai review is probably what it’s like to hold. With a shape like a camcorder, you’d probably assume that you simply grip it single handed with your right hand and shoot away. Sadly, this assumption is not correct. Despite it’s camcorder like shape, the Samurai is designed to still be used with both hands.

The Samurai’s user manual shows what they consider to be the proper way of handling the camera, which is with your right hand gripping the side of the camera and using your right index finger for the shutter release, and your left hand on top of the camera to both stabilize it and control the two zoom buttons. For photographs in a portrait orientation where you need to hold the camera sideways, you hold it almost like a pair of binoculars.

The two biggest issues preventing most people from using the camera single handed, is that the shutter release and two zoom buttons are not conveniently placed in a position that can be reached by the fingers of an average sized adult hand. The shutter release is easy enough to reach, but there is no way to get your fingers up to the two zoom buttons without having to reposition your hand. I have what I consider to be a pretty normal hand size, and it was just not comfortable for me.

But the bigger problem is that the black plastic body of the camera is not very grippy and the camera lacks any sort of “strap” that would secure the camera to your wrist, like you’d expect the see on most camcorders.

Kyocera did make two different styles of optional grips that can be installed in place of the normal battery door that allow for a much more secure grip of the camera, but I do not believe these came standard with the camera. In the image to the left, the one on the left is called the Action Grip SM-G1 and was made specifically for the X3.0, the cloth handled one on the right is the design for the X4.0. I am unsure if it also fits the X3.0.

Strangely, the Samurai X3.0 user manual doesn’t even make any reference to them being available. Perhaps they were created later on after the camera was already to market, but it just doesn’t appear to have been a common accessory. If anyone reading this knows anything about how these extra grips were available at the time of the Samurai’s release, please let me know in the comments section below.

Not having access to either of the two hand grip battery doors, my time with the Samurai required me to be very careful in holding the camera so that I did’t drop it. I wouldn’t say it completely ruined the experience for me, but it was there as a constant reminder each time I picked it up. Why Kyocera didn’t make either of these grips as a standard accessory on all Samurais is completely bizarre to me.

From top to bottom on the back of the camera, there is the rear eye piece for the viewfinder and a sliding diopter adjustment beneath it to compensate for the user’s vision. Beneath that is a small LCD screen showing the data back controls, flash mode, drive mode, and the exposure counter, followed by the control buttons for the rest of the camera’s settings and at the very bottom a small peep window that allows you to read the film information on an installed 35mm cassette. The available drive modes for the camera allow for single or continuous shooting, a 10 second self timer, and a 3-burst self timer mode which the manual suggests is useful for group portraits where you want 3 exposures of the same thing. Finally, there are two flash modes for night shooting, one that disables the flash and uses a slow shutter speed for low light situations, and another which is a combined slow shutter/flash mode where you can capture low light backgrounds with a flash burst to light up the foreground.

Fun Fact: The date back allows you to set a date as far forward as Dec 31, 2019, a mere 10 months from now! Imagine how far away 2019 must have seemed back in 1988 when this camera was first sold!

The colored bottom plate has a threaded 1/4″ tripod socket and the film compartment release for loading and removing film. The tripod socket is made of plastic so care should be taken when using the Samurai on a tripod to not stress it.

I didn’t bother to take a picture of the top of the camera as there’s nothing there, other than a metal plate with some holes that accept something called the “Portrait Flash Adapter” (part number SM-S1) which allows you to connect an auxiliary flash for more power.

The rear film door is awkwardly hinged at the top, right beneath the viewfinder and reveals the vertically traveling film compartment. Special care must be taken when loading film to not have the door slamming shut on you.

I’ve shot many half frame cameras, and even some like the Agat 18K that are vertically traveling, but this is the first example I’ve seen with modern features like DX encoding and a quick loading system. Simply extend the film leader to just below the red line above the take up drum, and close the camera and the camera will automatically detect film speed and advance the film to the first exposure for you. Annoyingly, when advancing film to the first exposure, it counts off eight (yes 8!) exposures, wasting considerable space on the film leader.

The Samurai supports DX encoding of speeds from 50 – 3200, and defaults to 100 for non coded film. I did not see any option in the manual to manually override the DX setting. The camera will automatically rewind a roll of film once it detects you have reached the end. There is an optional manual rewind button on the back of the camera if you’d like to rewind the roll mid roll.

On the camera’s left side is a prominent logo silk screened into the plastic, a neck strap loop, and a sliding shutter release lock that also functions as the camera’s power button. With this button in the up position, a red line is visible and the camera is powered on and ready to go. Push it down and the lens retracts and the camera powers down. Even in powered down mode however, the rear LCD will still show the exposure counter.

There is one more button on this side of the camera in the very bottom right corner, beneath the neck strap loop which is is indicated with the letters “RS”. The Samurai’s manual says this is a reset button to be used to protect the camera’s CPU in the event the camera detects an excess of static electricity. If this happens, a safety circuit disables all power to the camera, and you must turn off the main power, and press this button to disable the safety circuit.

The viewfinder is a bit on the small side and feels cramped compared to a typical SLR. Adding to the cramped feeling is there is some sort of circular glass element inside of the viewfinder that requires your eye to be perfectly centered to see the entire image. If your eye is off by even a fraction of a centimeter, the image quickly darkens. In the image to the left, you can see this effect through my smartphone camera. The edges of the viewfinder also have some type of softness like you would expect from a meniscus lens. I can’t be sure what exactly causes this, but it has to be a result of how Kyocera cramped a pentaprism viewfinder in such a small body. Don’t get me wrong, it’s usable and with your eye in that perfect sweet spot, I had no problems composing images, but it’s just a strangeness that isn’t present in most other SLRs. The viewfinder itself is pretty barren, save for auto focus brackets in the center of the image, and a red and green LED for “flash/slow shutter warning”, and “correct focus” indicators.

The Kyocera/Yashica Samurai is certainly an interesting camera, with a unique design, attractive red trim, and a feature set unlike many other cameras ever made. But what is it like to shoot?

My Results

As I do with most half frame 35mm cameras, I found a roll of 12 exposure film I had in my film drawer, and for the Samurai, I chose a roll of AGFAColor 200 that had an unknown expiration date. I like shooting 12 exposure rolls in half frame cameras as I can still get 24-26 images per roll and not have to force my way through 48 or even 72 exposures on a longer roll.

After developing the film, I thought the colors were unnaturally muted and lacking in resolution, so I decided to shoot a second roll of film. For that second roll, I chose freshly loaded Arista.edu 100 black and white film.

As it would turn out, I had some problems with the Arista film causing some streaks and scratches across the whole strip of film, but with two rolls of film shot through the Yashica, I felt as if I had enough to make a determination that while I was disappointed in both rolls, it was probably “good enough” for the target market.

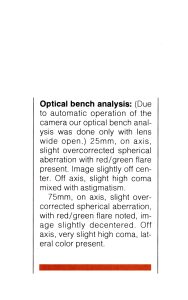

Sharpness in both rolls was consistent of a 14 element zoom lens made by a small company in the 1980s. While I am not lens optician, I have to imagine it is very difficult to get light to pass through 14 different pieces of glass, bending and curving through a 3x zoom range and not lose at least a little bit of sharpness.

A more disturbing problem was that the camera’s meter seemed to prefer overexposure on both rolls. This was especially noticeable in the Arista shots where skies were consistently blown out. Every black and white image above has some level of post processing where I had to correct the levels to make the images look as good as they do. I’ve shot that same film in other cameras and can confirm it’s not a result of the film itself. Whether this metering problem is inherent in the design of the Samurai, or due to some defect in the 31 year old electronics in this camera is uncertain. Looking at other sample images in Flickr’s Samurai photo pool seems to suggest that other people have gotten better results from theirs.

My experience with the Samurai was a bit of a mixed bag. I actually quite liked the idea of the camcorder form factor, but that you can’t comfortably hold the camera single handed is a let down. Having a SLR viewfinder that allows you to see through the lens in a half frame camera with a normally oriented viewfinder was also very cool, but the design of the viewfinder requiring your eye to be perfectly centered to see the image was annoying. Finally, shooting two rolls of film that produced softly focused images that had a tendency of overexposure, even if that was unique to this particular camera, was really disappointing.

I can forgive a fault in the electronics of the camera due to age, but if Kyocera/Yashica had included a hand strap with the camera when it was sold new and improved the viewfinder to work like a normal SLR’s viewfinder, this could have been a game changer. As it is, the Samurai is a curious relic of an era in the late 1980s when second and third tier electronics companies did some out of the box thinking with new camera designs. If you have a chance to pick up a Samurai it’s certainly a good conversation piece, and with the red trim is attractive, but just don’t spend too much money on it.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Yashica_Samurai_X3.0

https://www.flickr.com/groups/yashica_samurais/discuss/72157631484292548/

http://www.subclub.org/shop/yashsam.htm

https://www.35mmc.com/05/09/2018/5-frames-yashica-samurai-x3-0-fuji-superia-400-dan-marinelli/

http://darkroomist.com/2017/03/14/funky-yashica-samurai-half-frame-slr/

http://mailch.blogspot.com/2012/02/users-review-how-many-versions-of.html

https://www.photo.net/discuss/threads/yashica-samurai-x3-0-1987-or-1988.445605/

https://www.lomography.com/magazine/6956-yashica-samurai-x3-0-half-format-slr

http://blog.dcview.com/article.php?a=ATkDYFEyU2c%3D (in Japanese)

I used to have one and didn’t realize that the strap on mine was not standard. With the strap it was easily a one handed camera. It was a tight fit and held the camera firmly to your hand. I remember lusting after these at the Service Merchandise Store. I paid very little for mine about 7 year ago and sold it to a member of vintage camera collector page to thin out my collection.

Wow! Service Merchandise! That’s a store I haven’t thought about in years! There used to be one by the house I grew up, and I was always mystified at the conveyor belt that came from a second level where you would pick up your merchandise after paying for it!

As for the strap, I have to believe that at some point, after the Samurai was sold for a while, those straps were often sold along with the camera as an accessory. I just don’t believe that they came with them from the factory, at least not the X3.0 one.

You mentioned lens fungus in Samurais. Anecdotal experience: I’ve found fungus more frequently in legacy lenses of all brands – even the usually “fungus resistant” old Nikkors – I import from Japan than from other nations. Could this be because Japan is a land with high relative humidity and many non-air conditioned homes?

That’s a really good theory. Japan, especially near the shore can be quite warm, and without common conveniences of air conditioning in many homes, I could definitely see there being a correlation between Japanese cameras and lens fungus.

Another vertically traveling half frame 35mm SLR : Yashica Rapide

Yes, the Rapide is a neat little camera, although it’s not an SLR. I have the nearly identical Taron Chic that I’ll everyday review.

Thank you. I have two Samurais: x4.0 and x3.0.

When I place the battery in both, but not the film, the system starts but doesn’t allow me to zoom. Is loading a film necessary for testing the camera controls?

It is very possible that film is required for the camera to fully work. Sadly, I no longer have the Samurai I used for this review, so I cannot check for you.