I love prototypes! The promise of seeing concept models featuring designs or technologies that never came to be is very appealing as it offers a glimpse into what could have been. My recent post about a 53 page booklet from the Eastman Kodak company showed off some prototypes of cameras from 1939 including a 35mm version of the Kodak Medalist and a completely wild top of the line TLR concept that wold have put all others to shame. In a previous Keppler’s Vault, I showed off some Voigtländer prototypes from the 1950s including an SLR Vitessa and an updated Superb II.

While researching another camera for this site, I came across a prototype called the Konica Domirex, a strange looking compact SLR that used some kind of beam splitter instead of a moving reflex mirror to give through the lens composition in a compact leaf shutter camera that was nearly silent when shooting.

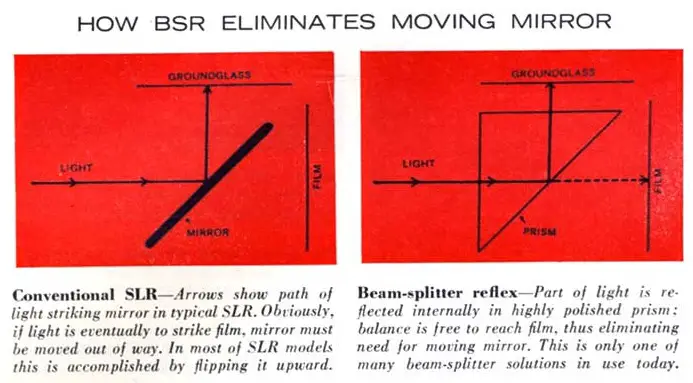

Fascinated with the concept, I did some research and discovered this article from the June 1964 issue of Popular Photography, which discusses a new concept in Single Lens Reflex cameras called the Beam Splitter Reflex or BSR for short. Where a SLR uses a mirror to reflect incoming light from the lens up through some kind of waist level or pentaprism viewfinder, a BSR uses a beamsplitter to deflect a portion of the light up through a viewfinder, and then the rest onto the film plane. This design has the advantage of not needing a large mirror that needs to flip up and out of the way at the moment of exposure, which causes viewfinder blackout, vibration, and a bunch of noise.

By using a beamsplitter instead of a reflex mirror, light is always available for the shutter to open and close the instant the photographer presses the shutter release. Not only is there no delay waiting for the mirror to move out of the way, but the viewfinder is never blacked out. Since the earliest SLRs, manufacturers found ways to minimize viewfinder blackout with instant return mirrors that only blackout the viewfinder for a small fraction of a second, but it’s still there. If you have a moving mirror, you’re going to have mirror black out….and noise…and vibration. Moving mirrors make noise and shake the camera, so when you get rid of the moving mirror, not only is the vibration gone, but the only sound is of the shutter itself.

In addition to these improvements, BSRs have many of the same advantages of a standard SLR in that the viewfinder shows a through the lens image of what will be captured on film the moment the shutter is opened. You can see depth of field and whether your image is correctly in focus while composing, and if you were to attach a lens with a different focal length, or some type of closeup filter, you’d see that too.

The downside of course, is that since the beamsplitter is only deflecting a portion of the light into the viewfinder, the image will always be darker than when 100% of the light is reflected using a mirror so any camera that would use this system would need to have a fast lens to maximize viewfinder brightness.

It’s actually surprising that it took until the 1960s for someone to seriously consider a beam splitter for an SLR as beam splitter viewfinders had been in common use in motion picture cameras like the Bolex Rex in which the camera offers through the lens composition through a beam splitter viewfinder that allows the photographer to see their image as the film will see it, without any blackout as the shutter opens and closes at speeds up to 64 times per second.

Beam splitters had also been in wide use since the 1930s in rangefinders, offering a combined image in which distance can be determined by viewing two separate images of a known distance apart, superimposed on top of each other.

The Popular Photography article takes a look at two very different types of BSMs, the first of which was a modified Visoflex reflex finder called the Camcraft Z Housing for the Leica M-series in which a standard reflex mirror is replaced with a fixed beamsplitter. The Camcraft Z Housing was available as a $125 upgrade to existing Visoflex owners. For as fascinating as this conversion likely was, it’s not the focus of this article.

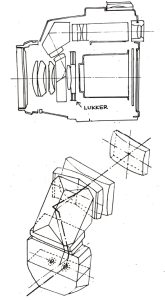

The other camera was a very interesting prototype called the Konica Domirex which made it’s debut at Photokina 1963. It was a compact 35mm camera with a 4-speed Seiko leaf shutter, shutter priority auto exposure, and with the exception of the small protrusion on the front plate of the camera, it looked like any other rangefinder camera of the day.

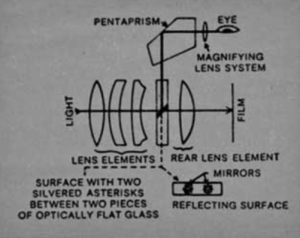

The Konica Domirex took the BSM idea to the next level, replacing a large beamsplitter with a flat piece of optical glass containing two very small “asterisk shaped” mirrors in the direct path of light in between the lens elements. Because they were located inside of the lens in front of it’s rear element, meant that the lens wasn’t designed to be changed. Had the camera gone into production, it likely would have been offered with some type of screw on wide angle and telephoto adapters like many rangefinder cameras of the day had.

Edit 2/17/2022: After posting this article, keen eyed collector Ira Cohen alerted me to a Domirex that recently sold on yahoo.jp for over a million yen. These six images are the highest resolution and clearest looks at a Domirex I’ve ever seen and give further insight into the design and functionality of this interesting camera. Perhaps what impresses me so much is how finished the camera looks. This does not at all look like a prototype, but rather a camera that was ready to sell.

I had to read this article several times and scour the internet looking for more information on the Domirex like this Danish language article before I started to understand how it worked so I’ll do my best to explain how it worked.

These asterisk shaped mirrors were designed in such a way as to maximize the amount of light reflected up into the filter, without reducing much of the light passed onto the focal plane. Despite being in the path of the light passing through the lens, the position of the mirrors was carefully selected so as not to show up in the exposed image. It would have been like having two small splotches of dirt inside of a lens in the exact position that wouldn’t show up on film.

Although the asterisk shape maximized the amount of light reflected up into the viewfinder, the image would have been quite dark on a piece of ground glass. Author Norman Rothschild estimated that the reflected amount of light was only about 20%. To overcome this, Konica completely eliminated the ground glass altogether, instead replacing it with a type of “brilliant” pentaprism in which the reflected image does not show depth of field or a correctly focused image. Instead, in the center of the viewfinder is a dual split image rangefinder, like those found on many SLRs of the day, but instead of only offering a horizontal rangefinder, it also offered a vertical rangefinder as well.

Sadly, none of the articles I’ve seen on the Konica Domirex show what the viewfinder looked like, but my best guess is that it would have been similar to the viewfinder of the Canon T80 which also offers both a horizontal and vertical split image rangefinder in the viewing screen.

In his review, Rothschild says that he had very little difficulty focusing the Domirex, even in low light. Later, he says that this focusing system is easier to use than on many ground glass cameras he’s seen, and that he hoped the Domirex would go into production with the same system as the prototype. Finally, in perhaps his most exciting claim about the camera is that the Domirex would have been perfect for people such as myself with poor vision and who rely in prescription eyeglasses while using a camera.

The Domirex prototypes seen at Photokina and in this article look like fully functional models. The top plate takes some styling cues from the Konica Auto S and S2. There is a meter readout, accessory shoe, film reminder disc, and threaded shutter release. On the front of the camera is the shutter speed selector and a flash sync port. Norman Rothschild says in his article that he was able to shoot some Tri-X film through it, suggesting a camera that was nearly ready for production. There were at least two different variants of the Domirex, the one seen here with a rectangular body mounted selenium exposure meter, and another with a round CdS meter in it’s place.

This Popular Photography article was written only a few months after the Domirex first appeared at Photokina, so the overall tone was very optimistic about it’s future, but as we know today, 55 years later, the camera was never put into production. Why it was never made is not clear, as companies rarely comment on why they don’t do things, but perhaps the concept of a beam splitter reflex camera with no ground glass, and double rangefinder system might have been a tough sell to customers.

The design of the camera wouldn’t have made interchangeable lenses easy. Norman Rothschild suggests that if an interchangeable lens were to be considered, the asterisk reflectors would have had to be included in each lens, likely raising the cost to make. In the event interchangeable lenses did become available, you’d still have the issue with vignetting from the behind the lens leaf shutter that would have affected longer lenses. Perhaps a later Domirex would have been offered with a focal plane shutter.

Also, without any type of ground glass or reflective mirror to separate light from the film plane and viewfinder, it meant that light entering through the viewfinder would have also gone into the film compartment, requiring some kind of shade to be present in the viewfinder as well. Some later SLRs would come with a viewfinder blind for this same purpose, but they were intended for long exposures where the photographer’s eye wasn’t blocking the viewfinder.

Perhaps a hint of why the Konica Domirex never made it into production comes from the Canon Pellix, a more traditional 35mm SLR released in 1965, less than a year after this article was written. Using a silvered reflex mirror, ground glass, and normal pentaprism design, the Pellix had a fixed semi reflective mirror that accomplished the same goal as the beamsplitter from the Camcraft Z Housing or Domirex that allowed light both to reflect up into the viewfinder and onto the focal plane, without having a moving mirror.

The Pellix had some of the same cons as the Domirex in that the partially reflected light caused a darker image, but with advancements in ground glass brightness and using fast Canon lenses, the viewfinder was still very usable.

With the Pellix, Canon was able to offer many of the benefits of the Domirex, in a much simpler camera that offered a traditional ground glass, a fully interchangeable lens mount, and a focal plane shutter which likely negated any demand for a camera like the Domirex.

Today, the thought of a camera with the combination of a compact body, a nearly silent leaf shutter, no moving mirror, through the lens composition, a unique viewfinder with a double split image viewfinder that was said to be great for people with poor vision, automatic exposure, and an excellent Konica Hexar lens is really enticing. I so wish this camera existed and I could get my hands on one and shoot it, but at the very least, I am glad I found this article so I could read about it.

For more information about the Domirex, check out these two sites: (both require Google Translate)

http://www.hexanon.net/konica_slr_detail/konica-domirex/

http://www.kamerasamling.dk/konica/konica_domirex.html

Finally, below is the Popular Photography article on Beam Splitter Reflexes, which inspired this article.

All scans used with permission by Marc Bergman, 2019.

Very interesting, Mike! I share your interests in technological developments in photography.

Another unmentioned drawback to the BSR (and Pellix) designs: Each places one or more additional pieces of glass in the light path, which can lead to image deterioration. Glass has a refractive index; it bends light rays. And over time, glass and mirror surfaces have a tendency to become hazy or dirty. All these issues can compromise the sharpness of the image that finally reaches the film plane.

That’s a good point. In the section of the original article about the Camcraft Z Housing, they further explain that the large beamsplitter also alters the focal length of the lens, which required some kind of extension adapter to restore the correct length. It would seem that there are multiple reasons why BSRs did not catch on!

Very informative research! Hexanon.net has added this link, thank you very much!!!