This is a Sony Mavica MVC-FD88, a 1.3 Megapixel digital camera that first went on sale in June 1999. The MVC-FD88 was part of Sony’s long running Digital Mavica series and stored it’s images on 3.5 inch floppy disks. At the time of it’s release, the FD88 model had the highest specs in it’s series, offering a 1.3 Megapixel 1/3.6″ CCD sensor and 8x optical, 16x digital zoom. The camera had a respectably large 2.5″ rear LCD screen on the back, an in body flash, and was also capable of up to 15 second MPEG audio and video clips. Although quickly superseded by quickly advancing digital camera technology, the Sony MVC-FD series remained popular for it’s quality images, ease of us, and convenience of not having to rely on proprietary memory cards and USB transfer cables.

Sensor Type: 1/3.6″ CCD 1.3 Megapixels

Sensor Type: 1/3.6″ CCD 1.3 Megapixels

Storage: 3.5″ 1.44MB Floppy Disk

Lens: 4.75 – 38mm (41 – 328mm equivalent) f/2.8 – f/3 zoom Sony Lens coated unknown elements

Focus: 1 inch to Infinity, Macro and Manual Focus modes

Viewfinder: 2.5″ 180,000 pixel Color LCD

Shutter Speeds: 1/30 – 1/4000 seconds, stepless

Exposure Meter: Fully Automatic Program AE

Battery: NP-F330 Lithium-Ion 8.4v Battery Pack

Flash: In-body Electronic Flash, unknown sync-speed

Weight: 700 grams (w/ battery, no disk)

Manual: https://www.sony.com/electronics/support/res/manuals/W000/W0007221M.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Sony Mavica MVC-FD88 was a mid-level model in Sony’s early Digital Mavica lineup and stored 1.3 megapixel images on 3.5″ floppy disks. The use of commonly available floppy disks meant that the camera’s images could easily be viewed and shared on nearly every PC at the time instead of having to rely on proprietary flash cards or USB cables. As a result, the Digital Mavica series sold well and introduced digital photography to a large number of people who otherwise might not have been interested. I had a lot of fun playing with this camera and the images I shot were surprisingly good, especially for a 20 year old digital camera. The use of 1.44MB floppy disks was also the camera’s greatest weakness too, as at the camera’s highest resolution, meant that no more than six images could fit on a disk. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0% | |

| Bonus | +1 for historical importance, the use of 1.44MB floppies meant it could be used by nearly anyone | ||||||

| Final Score | 9.0 | ||||||

History

Today, Sony is one of the leading makers of digital cameras. Their Alpha series of digital mirrorless and DSLR cameras are extremely popular and rival that of much more established camera makers like Nikon and Canon.

That wasn’t always the case. In fact, Sony really didn’t make a strong effort in the photography market until their acquisition of Konica/Minolta in 2006. Prior to that, the brand name Sony was most well known for their vast lineup of televisions, VCRs, audio equipment, and the Sony PlayStation video game console.

That wasn’t always the case. In fact, Sony really didn’t make a strong effort in the photography market until their acquisition of Konica/Minolta in 2006. Prior to that, the brand name Sony was most well known for their vast lineup of televisions, VCRs, audio equipment, and the Sony PlayStation video game console.

Originally founded on May 7, 1946 as Tōkyō Tsūshin Kōgyō, or Tokyo Telecommunications Engineering Corporation, by a Japanese electronics industrialists Masaru Ibuka and Akio Morita, the company’s early products were primarily in the audio recording market. Their first product was a reel to reel tape recorder called the G-Type which was created primarily for the government.

Throughout the 1950s, Tōkyō Tsūshin Kōgyō would use a shortened version of their name, Totsuko, in marketing within Japan, but this name was not used in western countries like the United States as it was determined to be too difficult to pronounce.

As a result in 1955, the company would start using the name Sony on some of it’s products, which was chosen as a mix of two words, the Latin word “sonus” which is the root of “sound”, and “sonny” which was a slang word for a young person. The idea behind the two words was that the company name Sony would evoke youthfulness while keeping in line with the company’s audio roots. In 1958, the company would officially become known as Sony.

Sony’s TR-series of transistor radios were their first internationally marketed product using the Sony name and were an immediate success all over the world. The Sony TR-63 was the first product sold in the United States. A fun fact about the TR-63 is that it was marketed as a pocket-sized radio, but was slightly larger than the pockets found on most men’s shirts of the day, so Sony had specially designed shirts made with oversized pockets to be used by salesmen to show off the pocketability of the slightly larger radio.

Throughout the 1960s, Sony’s place in the market grew by leaps and bounds. They created the world’s first fully transistorized television in 1960 and their transistor radios were extremely popular with American teens and others looking to take their music with them. By the 1970s, Sony had expanded into a large number of other markets including their own life insurance company and were one of the early developers of the Compact Disc.

In the 1980s, Sony was on a roll, creating the Betamax video cassette format, the Walkman, the NWS-830 personal computer, in 1988 bought CBS records, and in 1989 bought Columbia Pictures extending their reach into markets far beyond that of simple handheld radios.

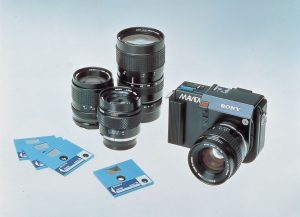

But it was another invention from 1981 that barely made a splash on anyone’s radar which later would have a ripple effect of which we are still feeling the effects of today. On August 25, 1981, Sony would announce the release of the Sony Mavica, the world’s first filmless electronic still camera. The name Mavica is said to stand for “MAgnetic VIdeo CAmera”, and wasn’t a true digital camera, but rather a type of motion video camera that captured still images and stored them on a proprietary 2 inch “Mavipak” floppy disk format that Sony had developed for the Mavica.

The Sony Mavica was the first still video camera in the world upon it’s release and was presented in a familiar SLR style with it’s own unique interchangeable bayonet lens mount. Three lenses were available for it, a 50mm f/1.4, a 25mm f/2, and a 16-65mm f/1.4 zoom. The image to the right shows the Mavica with all three lenses (the 50mm f/1.4 is shown twice), and a couple of the Mavipak 2″ disks.

Images stored on the camera could only be displayed on a television or video monitor connected to the camera. The images had an approximate resolution of 570 x 490 which had it been a digital camera, would have been stated as 0.27 megapixels. Each Mavipak disk could hold up to 50 images on a single disk.

The camera had an ASA 200 equivalent sensitivity and only a single 1/60th shutter speed. The metering system displayed LED arrows visible in the viewfinder and required the user to manually change aperture on the lens to get the proper exposure.

I can only imagine the excitement this camera must have received when it was first announced as it gave the first glimpse into a filmless future. Although only ever produced as a prototype, the design of the camera seems really well thought out, suggesting that the prototype was fairly close to a production model, yet the camera never went on sale.

Sony would release a couple different Mavica prototypes in the years that followed, but it wouldn’t be until 1987 when their first commercially available model, the Mavica MVC-A7AF would hit the market. Using the same still video capture onto 2″ floppies (now called VF or video floppies), the MVC-A7AF had a full range of shutter speeds and automatic focus, but lost the interchangeable lens mount, instead featuring a fixed 6x 12-72mm zoom lens.

By the late 1980s, Sony wasn’t the only company in the still video camera market as Nikon, Canon, Philips, Panasonic, and even Kodak all released various prototypes and commercially available still video cameras.

During this era of still video cameras, the 35mm film camera was still king. Nothing would seriously challenge the dominance of film cameras for at least another decade, but that didn’t stop innovation as many manufacturers continued to explore the format.

By the early 1990s, the still video camera market would be replaced by true digital cameras. Most of the earliest digital cameras were adapted film cameras often made by Nikon or Canon, in which the backs of the camera were replaced with some type of electronic digital sensor that at first was connected to an external storage device, but would later feature removable storage formats.

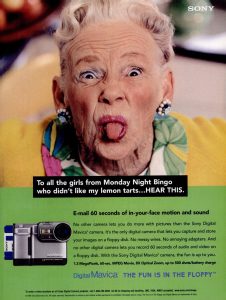

Sony would remain relatively quiet in the photographic world until 1997 when they would relaunch a new lineup of Mavica cameras. This time instead of still video technology, the cameras would be true digital cameras, writing images to a standard 3.5″ magnetic floppy disk that could be read by any Windows or Mac based PC.

The first two models, now referred to as “Digital Mavicas”, were the MVC-FD5 and MVC-FD7 which launched a form factor that would be used with the entire Digital Mavica lineup. The first models were capable of only a 640×480, or 300 kilopixel resolution, but as each new model was released, the features and quality of the cameras would improve.

The model being reviewed here is the Sony MVC-FD88 which when released in 1999 was one of the higher end models, featuring a 1.3 megapixel sensor, 8x optical zoom, and video capture capabilities. When it sold new, it had an MSRP of $999 which when adjusted for inflation is comparable to $1550 today making it quite the investment for an unproven camera technology from a company not well known for their work in the photography industry.

In a review published in the August 26, 1999 issue of the Arizona Daily Star, David Wichner comments how the adoption of digital cameras has been slow due to the proprietary need of flash cards and serial cables but Sony’s Digital Mavica eliminates that obstacle, likely turning a larger group of people onto digital cameras.

Today, we have the benefit of hindsight to know that Wichner was right. Sony’s Digital Mavica series succeeded in ways other early digital cameras didn’t with the convenience of using regular floppy disks. This convenience came at a cost though, which was capacity. The lower resolution of the earlier models could fit as many as 40 images on a single disk, but as the resolution and file sizes grew, the capacity dropped quickly to as low as 4 images per disk for the later models.

To combat this, Sony would eventually release models that supported their new Memory Stick flash card, and some that could save their images to 8cm recordable CDs. With a capacity of 156MB, Sony estimated that each CD could hold up to 237 images at the camera’s highest resolution.

By the time these models hit the market in 2001 and 2002, people’s preferences for how a digital camera should look and work were more favoring flash memory storage, plus 8cm recordable CDs weren’t as common as other disc formats making them somewhat less attractive. As a result, in 2003 Sony would discontinue their Mavica lineup of digital cameras.

Sony’s next big step towards market dominance came in 2006 when they would purchase the entire camera and photography division of the Konica Minolta Corporation. Both Konica and Minolta had a long run as two of Japan’s premiere optics companies of the 20th century, but in 2003 fell on hard times and merged together with the hope that two struggling companies could survive together. That didn’t happen, as barely 3 years later, the company was looking to shudder their entire photography divisions and on March 31, 2006 agreed to sell to Sony.

With their acquisition, Sony acquired all of the technologies and trademarks from the long running Konica and Minolta brands, including the Minolta alpha mount which was the basis for Sony’s new alpha series of DSLRs first introduced as the Sony Alpha 100. Sony would use their considerable manufacture and design experience to continue where Konica Minolta left off, continuing to refine existing and develop new technologies that would go into their cameras.

Sony’s reputation and understanding of what photographers expected from their cameras continued to grow over the next decade to where they make some of the most popular DSLR and digital mirrorless cameras today.

As recently as 2018, Sony accounts for nearly a quarter of the world’s still camera market by revenue, putting them ahead of Nikon and barely behind Canon.

Today, there is a very small, but growing niche of collectors who seek out early digital cameras. If you like cameras with quirky designs that require obstacles not needed on a modern camera to get a picture from it, then the Sony MVC-FD88 is a great start. The reliance of floppy disks certainly qualifies as a “quirk” as modern PCs no longer have 3.5″ floppies, yet they’re not so obsolete that you still can’t get them. In fact, compared to other digital cameras from 1999, I’d say this camera is easier to use than others which require an early form of USB or SCSI connection to a PC and software which might not even compatible with modern operating systems. I don’t know how many people collect old digital cameras, but I would be willing to bet that for those that do, having a Sony Digital Mavica is a no brainer.

My Thoughts

In the mid to late 1990s, I worked for a major electronics retailer called Best Buy. During my time working for the company, I remember when the Sony Digital Mavicas hit the market. They were basically like mini computers that took electronic photos and stored them on a floppy disk. The concept was very cool, but holy cow were they expensive!

The MVC-FD88 reviewed here retailed at Best Buy for $899.99 when it was new, far exceeding the meager paychecks I was earning at the time. In those days, I would have dreamed to have a chance to play with such cutting edge technology. As the saying goes, “good things come to those who wait”, and 20 years later, I got my chance!

That day would eventually come in the summer of 2019 when I was visiting Gary Camera in Merrillville, Indiana. I often stop in to the shop to visit the owner Barry, drink some of his coffee, and chat about cameras. On occasion he lets me sift through bins of old cameras that people drop off for him. On this particular day, beneath several layers of 80s and 90s point and shoots, I saw not one but two of these floppy disk Sony Mavicas. I picked up the nicer of the two and thought, boy would this be fun to play with if only I could find the charger for the proprietary battery. Upon continued digging through the bin, there it was, wrapped tightly with a dry rotted rubber band, the charger!

Both the charger and the camera were in excellent condition. If I were a Japanese eBay seller, I would describe this one as TOP MINT++++. The camera looked barely used. All of the original promotional stickers were still on the camera and showed no signs of fading or peeling. Almost like this thing traveled through time from it’s original packaging in 1999 to that bin in 2019.

After an undisclosed amount of money, the Sony came home with me. I was delighted to see that the battery not only accepted a charge, but I was able to power on the camera and see the camera’s splash screen for what was probably the first time in well over a decade.

I was strangely excited to shoot the MVC-FD88, even more so than many much more capable film cameras. While I had no expectations that this thing would rival the picture quality of even an entry level point and shoot 35mm camera, I have a fascination for old technology, and for someone who reviews old cameras, what could be more perfect than a digital camera that uses floppy disks!

Satisfied that the camera was in working condition, I scrounged around my house looking for some disks and I found a box of them in my basement. I formatted them using the camera’s menu function and went shooting.

Starting with the top of the camera, there’s not much to see as most of the camera’s controls are on the back. From left to right is another colorful promotional sticker, then the microphone opening for recording videos on the camera, and then on the right is the shutter release button. Finally, near the very back of the top plate is a thin rectangular piece of plastic that acts as a ambient light window for using the rear LCD with the back light off.

The bottom of the camera has all of the typical consumer information stickers you’d expect from a modern electronic device, along with a metal 1/4″ tripod socket, and the opening for the proprietary lithium-ion battery pack.

The camera’s right side is dominated by the floppy disk drive. The entirety of the 3.5″ opening for the drive extends from the very top to bottom of the camera, which is responsible for the camera’s tall shape. As we would come to learn, later digital cameras would take on a shape more in line with that of traditional 35mm film cameras, so the shape and size of the entire Sony MVC-FD series was borne out of the need to fit the disks in the camera.

The camera’s left side features the auto/manual focus switch and an A/V out port for displaying a slideshow of stored photos and videos on a television screen. A/V outputs are still commonly found on many digital cameras today, so it’s notable to see this feature included on such an early example of a digital camera.

The back of the camera is cluttered with buttons and the large 2.5″ TFT LCD display. Most of the buttons are clearly marked so I won’t explain what each of them do, but the most important ones are the “T/W” zoom slider in the upper right corner, the sliding power switch with teal colored safety button, and near the bottom right corner is the eject slider for the 3.5″ disk drive.

The viewfinder takes up the largest portion of the back of the camera. I can’t prove this, but the 180,000 pixel resolution and style of this screen looks like it was lifted straight from a Sony camcorder parts bin as it’s resolution is more VHS quality than what you’d expect from a later generation digital camera.

There is no optical viewfinder on this camera, so the LCD screen is your only option for composing and reviewing your shots. The back light can be disabled to save on battery life when using the camera outdoors in bright light. A rectangular window on the top plate of the camera above the screen allows sunlight to illuminate the viewfinder. I tested this in bright sunlight a couple of times and with the back light off, the viewfinder isn’t quite as bright, but it’s surprisingly effective allowing you to fully use the camera while increasing battery life.

The front of the camera has no controls other than the manual focusing ring on the lens itself. I tried manual focus a couple of times on some closeups and found it extremely difficult to use. Like most digital cameras lacking in an optical viewfinder, you have to rely on the LCD screen to “see” focus, but the low resolution of the 2.5″ TFT makes this very hard to do. While I appreciate the inclusion of such a feature, it’s almost useless and something first time digital camera buyers in 1999 likely would have never used anyway.

The camera’s large size and comfortable hand grip make it very easy and comfortable to hold, but it’s large size eliminates any chance of sticking this thing in a pocket.

Compared to digital cameras that came a couple years after it, the Sony Mavica MVC-FD88 is certainly an odd duck in use and size, but it’s clear Sony took these cameras seriously as the build quality is quite good. The camera is solid and feels well built. It doesn’t creak in your hands and all of the tactile controls are up to the usual standards Sony was (and still is) known for.

My Results

For my first roll of film through….errr, wait a minute. Considering how often I test film cameras, my initial reaction was likely the same as someone seeing this camera when it was first released. For many people, the Sony Mavica series was likely their first experience with a digital camera, and the idea that you could just keep taking photos without ever having to buy new film or get it developed was likely a shock!

Of course, it’s now 21 years later and shooting film for most people is the weird experience, so for my first roll…dang it, did it again…with this MVC-FD88, I tried to take random pictures of everyday life like someone who bought it in 1999 probably would have.

My first ever digital camera was a Toshiba PDR-M25 that I bought for around $200 in early 2002. That camera had a 2.2 megapixel sensor, 3x optical zoom, and a tiny rear LCD screen. It was a fine first digital camera for me, but I quickly grew tired of it’s limitations. It had very poor low light performance and even in ideal lighting conditions, colors were always washed out. I kept that camera for about 2 years before upgrading to something much better, and looking back upon those pictures today, the difference between it and my next camera was significant.

Over the years, I’ve seen some pretty terrible early digital camera pics and looking back at the images from that old Toshiba, I expected the worst when I began shooting with the Sony MVC-FD88. After all, this camera was three years older and had even less pixels, so the images were likely going to be atrocious, right?

To my surprise, when I loaded the images onto my PC from the camera, they were better than I thought they’d be. Remembering the poor low light performance of my old Toshiba, I tried to shoot the Sony mostly in bright sunlight and looking at them on my 27″ monitor, they didn’t look bad and certainly could stand up to being printed at 4×6 or even 5×7. Colors were fairly accurate, resolution was acceptable, and the exposure was close enough.

My praise for the images ends the moment you try to zoom into an image as with a resolution of only 1280×960, there’s less detail than I get from 35mm scans on my Epson V550 flatbed scanner. I also noticed that the camera had almost no latitude for brightness and shadows within the same image. Highlights are clipped in almost every image and shadow detail is moderate at best.

Although I shot many images in bright sunlight, I found the best looking images were ones shot outdoors in the shade or under overcast skies. The pictures of the old automobiles in the gallery above looked great as they weren’t in direct sunlight. The indoor shot of my cat and the film cameras is badly exposed and loaded with chroma noise. Turning the flash on and taking another image of my cat eliminated the chroma noise, but blew out the details making for a very harsh looking image.

I even tried a couple macro shots in manual focus mode and found focusing on the low resolution LCD to be extremely difficult. Seeing focus on the LCD screen, especially outside in bright sunlight was very hard. Although the camera impressively boasts a 1 inch minimum focus, I don’t think many people would have been successful with it.

Those complaints aside though, I was pretty happy with the images I got. I can wholeheartedly say this Sony outperformed my first Toshiba, but then again, you’re talking about a camera that originally retailed for 5 times as much so I think it’s fair to expect a little more.

I can also offer a bit of praise to the Sony NP-F330 Lithium-Ion battery pack as I was able to shoot all of the images in the gallery above over the course of a couple of days on a single charge. Considering this is likely the original battery that came with this camera 21 years ago, the fact that it’s still able to power the camera and hold a charge suggests it likely lasted quite a while when it was new.

By far, the number one biggest complaint about this camera is it’s use of floppy disks as a storage medium. Not only is the drive very loud and slow to write images, at the camera’s highest resolution, each 1.44MB disk could only hold 5, sometimes 6 images before I had to eject the disk and load up another. Dropping the quality level from Fine to Standard didn’t improve matters nearly as much as the manual suggests as my limit still seemed to be no more than 6 images. If I was willing to drop the resolution down to 640×480, the manual suggests between 25 to 40 images per disc, but frankly at that quality, I don’t know that the images would be useful for anything more than thumbnails.

I remember the frustration of early competing flash storage formats, there was SmartMedia, Memory Stick, Multimedia Card (MMC), CompactFlash, and many others that have all since either disappeared or been replaced by later variants, and finding the right card with the right reader, and the right USB transfer cable was frustrating. The use of 3.5″ disks that every computer at the time supported would have been a perfect solution had it not been for the capacity limitations.

When shooting old film cameras, I often speak of using a camera to it’s strengths. You’re not going to shoot an 80 year old scale focus film camera with a sluggish shutter indoors at minimum focus. You’re going to want to look for scenes that work best for what the camera can do, and that still holds true for early digital cameras.

Although I was not the target market for this camera when it was first released, I do remember the appeal of not having to pay for and develop film with every image I shot. I loved the convenience of being able to review and delete an image on the rear LCD screen if I didn’t like it. Early digital cameras were more about convenience than quality, and for a floppy disk digital camera from 1999, the quality was a lot better than I had expected!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sony_Mavica

https://www.cnet.com/products/sony-mavica-mvc-fd88-digital-camera/

https://www.kenrockwell.com/tech/fd88.htm

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hM1DoYkx1XM

https://www.techrepublic.com/article/introducing-the-sony-mvc-fd88-digital-camera/

Thanks Mike for continuing to post interesting commentaries in these days of covid-19 and lock-downs. Cheers me up!

I’m glad they bring you some form of relief. For me, continuing to type these up also helps me feel some level of normalcy by doing something I like, rather than worrying about what’s going on in the world.

I borrowed an FD88 from a friend in 2000 to take some pictures of a house that my wife and I were having built — while in progress. For a clunky camera with a very non-film-camera feel, it really did produce very usable “archival” images. I never realized how much money it was new! Stay safe Mike and family!

A nice review, as usual. The only time I came close to a Mavica was back in 1999 during my Legal Medicine class. The local forensic team used one to take pictures during the autopsy and the technician came with the pockets if his lab coat full of 3,5in floppies. He would shot a few images , remove the floppy and put back into the pocket, load a new one and keep on. That day he may have spent some 40 floppies in an hour and a half. It was almost magical to me, at the time keen user of my dad’s Canon TX…. when I had enough money to buy film and develop ir, that is.

Great story Gorka, thanks for sharing. The need to constantly swap disks is rather inconvenient as you could argue that having a single roll of 36 exposures is easier to deal with than a pocket full of floppies, but at least the disks can be reused. Once you transfer the data to the PC, you didn’t need to keep buying new disks. Still, it was a very cool proposition back then and something I remember being fascinated with when I first saw these cameras.

It is important to remember that early digital equipment ages in dog years. 1=7. This Sony is well over 100yrs old! I’m finding that playing with old digital cameras is lots of fun. The limitations test your skill, and the costs are very low. Lots of interesting designs from which to choose.Thanks for the review!

Good point Kurt! From now on, any digital camera reviews I’ll have to use your “dog years” rating system! 🙂

“Sony’s next big step towards market dominance came in 2006”.

Mike, You place me at odds with this comment. Sony was a significant player from the turn of the millenium with its F range culminating in the F828 8mp model of 2003, and before this it was competing with many consumer orientated models, such as the well spec’d DSC V1, for example. Then there was their masterpiece, developed without any Konica/Minolta input. I’m referring of course to their superb DSC R1 in 2005. The acquisition of K/M did open the road to their future developments, but they had already proved that they had considerable expertise up to this point.

The Mavica’s are very interesting early attempts, I have a floppy version and memory stick, also the CD500. This latter model is 5mp and possibly the best OOC jpegs I’ve seen when used in sunny weather. Colour is very natural, and clean.

Maybe I could have worded that differently, but I don’t think anyone could argue that Sony’s acquisition of Konica/Minolta in 2006 was a big deal not only for Sony, but for the whole photography industry. You’re right as they had some solid models before that, but I think that the number of people who would have considered Sony a serious player in the photography market in 2005 or before, was very small.

Your praise for the CD500 might make me want to seek one out. I imagine finding the disks these days is quite difficult though.

Mike, I don’t know if the consumer preferences in the US and UK differed, but here Sony was established as a consumer digital camera company well before their takeover of K-M. But with their R1 they’d taken non-slr cameras about as far as they could, but as imaging-resource pointed out in their review, it was at a time when the first dslr’s were breaking the $1,000 barrier. But the R1 was the world’s first APS-C bridge camera, and with a cracking lens to boot. In fact I-R compared the image quality of the fixed Zeiss 24-120mm(equiv) lens to a Canon system and for which to cover the same focal range and quality, one would need three lenses, putting the total cost at around $2,900. So if the focal range suited, and one didn’t want the bulk of two extra lenses, then the R1 should have been a no-brainer at $999. But the lure of dslr meant there was never an R2.

As for the CD500, I’m a little surprised that they are not as cheap as I may have expected over here for old digital kit. Or is it sellers are being very speculative in their asking prices? Some US prices filling the bottom rung, around $25 to £35. 8cm discs, both CD-R and CD-RW, are readily available here, and are not excessively priced at around $8-$9 for 10. But for testing you only need one CD-RW.

My first digital camera was a Fujifilm Finepix E500 https://www.imaging-resource.com/PRODS/E500/E5A.HTM

It was quite a departure from the film cameras I’d used and the tiny xD chip amazed me at the number of images that could be stored on it.

I recall reading about the Sony Mavica cameras, but even in the late 1990’s, 3.5″ 1.44MB floppies were an odd/limiting storage medium. In spite of it’s limitations, the E500 was my “event camera” until the call of the DSLR finally got to me.

This led to a Radio Shack sale bundle, a Nikon D40 with a 2 kit lens package in the early 2000’s. That not-exactly-electronic-Nikon-FM kept me going in the DX world, though I envied the Nikon D7000 outfit a former camera club photographer wielded with an 18-200mm lens.

Eventually, eBay proces for the Nikon D7000 body dropped enough for my trailing edge budget and I added Nikon FX lenses to the collection, as “The Angry Photographer” suggested. So, I went from 4.1MP to 6MP to 16MP over time, which is where I stopped. (Megapixel madness and “”how well does it do video?” battles and the rise of the SmartPhone camera put me off.)

It’s not vintage enough, so I’ll likely never write about it, but the Nikon D7000 was my every day DSLR for about 6 years before switching to the Fuji X-T20 that I use today. For my money, the D7000 was Nikon’s best “compromise” model between their entry level 3000 and 5000 series cameras and their pro ones. It had a weather sealed magnesium body, in body focus (for compatibility with older AF lenses), their top of the line (at the time) focus system, and about as many shooting modes as you could want. I still love my D7000….damn, maybe I should write about it! 🙂

Loved all the info about the MVC-FD88. I still have mine –and the battery charger — a bunch of floppy disks and a floppy disc reader that I bought later I feel VERY LUCKY since I loved using this camera. BUT I NEED HELP. The last floppy disk inserted was put in the wrong way and I haven’t been able to extract it. The ejector slide is jammed, too. How would you advise opening up the camera to retrieve the floppy, and HOPEFULLY be able to use it. The camera & accessories have been in store for a number of years.

Meg, I am glad you enjoyed reading the review. In regards to opening the camera however, I wouldn’t even know where to begin. It’s one thing to take apart an old mechanical rangefinder from the 1950s or a folding camera from the 1930s, but an electronic digital camera from the beginning of the 21st century is going to be prohitively more difficult. I don’t know know anyone who services these, so sadly, you might be out of luck. If you’re willing to give it a go, I guess I would start with all visible screws and see where that takes you. Make sure you use GOOD precision screws as Japanese screws are slightly different from regular ones. Make sure any you get are labeled as “JIS”. Good luck!

Meg, before you attempt to take apart your Mavica, you may wish to try a less invasive approach to start with.

I’ve just checked my FD71 and found that the dust flap can be pushed open manually. Now if you can fabricate a rod to insert into the open flap and such that it can reach the disc, you may wish to apply some super glue to attach the rod to the disc. Leave it plenty of time for the glue to set, say 24 hours, then with the disc release switch held in the disc eject position, see if you can pull the disc out.

If this fails and you still wish to “have a look inside” check which screws to indo. On the FD71 there is a small arrow pointing to each screw that will need to be removed. As far as I am aware, there is no set sequence.