This is a Graflex Graphic 35 Jet, a 35mm rangefinder camera produced by Kowa Optical Works of Japan for Graflex, Inc of Rochester, NY starting in 1961. The Graphic 35 Jet is an evolution of the earlier Graphic 35 which itself evolved from the Ciro 35 and Cee-Ay 35 cameras. The inclusion of the word “Jet” in the name is because this camera had a unique ability to advance the film and cock the shutter via a proprietary compressed CO2 cartridge that would slide into the bottom of the camera. Around the time this camera was made, camera companies were looking for innovative ways to “motorize” their cameras, and while many companies settled on a simple wind up clockwork system, Graflex (and Kowa who made it) went for compressed gas.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 50mm f/2 Graflex Optar coated 6-elements

Focus: 3 feet to Infinity, Push Button Focusing

Viewfinder: Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder

Shutter: Copal SVK Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: Coupled Selenium Cell w/ top plate match needle

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Coldshoe and M and X Flash Sync

Weight: 796 grams

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/pdf_files/graphic_35_jet.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Graflex Graphic 35 Jet was the last of many things, including the last new 35mm camera produced by Graflex. It was also the last (and first) “jet powered” camera that used compressed CO2 to power the film transport and shutter. It is certainly an oddball camera, but it’s large size, sharp angles, poor ergonomics, and a curious selection of control locations make it quite an unpleasant camera to shoot. Which is a shame as the idea was cool and I believe the Kowa designed 6-element lens had the potential to make this camera a winner. This camera is deserving of a place on your shelf for it’s neat looks and oddball features, but nothing more. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 20% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 7.2 | ||||||

History

When it comes to the name Graflex, the first thing most any photographer will think of was one of their hugely successful large format cameras produced throughout the 20th century. Graflex press cameras like the Crown and Speed Graphic series dominated newsrooms all over the world and were often seen as the “de facto” standard for the news photographer.

Originally formed in 1887 as the Folmer and Schwing Manufacturing Company by William F. Folmer and William E. Schwing, the company produced a variety of gas lighting fixtures, lamps, bicycles, and starting in 1898, cameras. Their Graflex Reflex series came with focal plane shutters and proved to be popular and competed with the likes of the Scovil & Anthony Companies line of similar cameras.

Between 1905 and 1906 the company was acquired by George Eastman and became the Folmer & Schwing division of Eastman Kodak. A variety of new twin lens, stereoscopic, sheet film, and roll film cameras were released by the company over the next couple of years.

In 1912, the first Speed Graphic press camera would be released that would be the foundation for a successful line of press cameras that would stay in production until the early 1970s. The Speed Graphic would launch several other models, some with focal plane shutters and others with leaf shutters.

The rapid success of the Folmer & Schwing division of Kodak was so successful that in 1926 the company was found by the US government to be in violation of the Sherman Anti-Trust Act and two years later, was forced to split off it’s Graflex division into a separate company which would be known as the Folmer Graflex Corp of Rochester, NY.

During World War II, Folmer Graflex would produce a variety of aerial and military use cameras that were used by Allied forces. Their press cameras remained popular back home and continued to sell well in the years that would follow. Perhaps in an effort to clearly identify themselves as the maker of Graflex cameras, in 1945, the company would once again change it’s name to Graflex Inc.

It was during these years that Graflex cameras saw their greatest success. Press photographers regularly used Speed, Crown, and Century Graphics almost exclusively. Although exact production numbers were not kept, efforts to analyze production numbers by serial numbers suggest that total production extended into the several hundreds of thousands.

Perhaps in an effort to expand their product offerings, around 1949, Graflex started to put their name on smaller 35mm and 120 roll film cameras. The first such model was the Graflex Ciro 35 in 1949, which was based off earlier Perfex cameras produced by the Candid Camera Corporation of Chicago. In 1955, the Ciro 35 would be heavily redesigned and turned into a new camera called the Graflex Graphic 35.

The Graphic 35 was an ambitious American made 35mm rangefinder camera that used West German Rodenstock lenses and a Prontor leaf shutter. The camera had a unique push button focusing system in which two rectangular paddles, one on each side of the lens, would be pushed to move the entire shutter and lens assembly fore and aft to adjust focus.

Combined with a unique shutter release lever immediately below the right focus paddle, the idea behind this system was that the photographer could focus and then release the shutter to make a photograph without ever having to change the position of their fingers.

The Graphic 35 would be the last Graflex 35mm camera to be produced in the United States when it’s production ended in 1958, although the camera would still be sold by dealers as late as 1960. At this time, the only other 35mm camera being sold by the company was the more traditional Graflex Century 35. This camera was built for Graflex by Kowa of Japan and was a variant of Kowa’s Kallo 35 rangefinder featuring a coincident image coupled rangefinder, Kowa shutters and lenses, and more traditional styling with a shutter mounted focus ring and a top plate shutter release. At least two other Kowa built Graflex Century cameras were made at this time, one which was a simple model without a rangefinder, and the other with a selenium exposure meter.

During this time, work would begin on an all new camera that Graflex would design, but Kowa would build. A year earlier, Graflex had previously released a model called the Graphic Electric 35 which was built for them by Iloca, but production on that camera ended abruptly in mid 1959 due to Iloca’s acquisition by the Zeiss Group who owned Deckel, who produced the lens mount and shutter for it.

Graflex was clearly showing an interest in automatic film advance cameras as the Iloca Electric used a simple battery powered electric motor to advance the film and cock the shutter each time the shutter was pressed. Although this is how pretty much all cameras work today, in 1959, this was state of the art stuff as no one else had a camera with a built in electric drive.

With their new camera, Graflex wanted something that didn’t rely on complicated electronics, and instead went with the most logical choice….compressed gas.

Let that sink in. Yes, compressed gas…from a CO2 cartridge…like in a BB gun.

This new camera, which would be called the Graflex Graphic Jet, was envisioned by Graflex’s President G. C. Whitaker and would be entirely designed by Graflex. Graflex would build the Jet motor drive, but the rest of the camera would be built by Kowa in Japan, and would use a Microwatt exposure meter made in Germany. During development of the camera, the specifications of the Jet motor drive changed several times as nothing like it had ever been built before, and there were problems communicating the drive’s changes to Kowa, which resulted in early cameras not working correctly.

These almost constant last minute changes put a strain on Graflex’s relationship with Kowa and caused it to deteriorate. Further complicating matters, was once a new CO2 bottle was inserted into the camera and the bottle’s seal was pierced, constant pressure needed to be maintained by the camera to prevent the gas from leaking out. This required special high pressure o-rings which Graflex had problems sourcing, so a different kind of o-ring was used that would hold up to the pressure initially, but would quickly start to leak.

The Graphic Jet was doomed from the moment it was released and sold poorly. When it became clear the camera wouldn’t be a sales success, production of the CO2 bottles was discontinued and remaining stock of the cameras were modified to remove the Jet motor drive. The camera was wisely designed in a way where there was a mechanical backup to the Jet drive in case the bottle was empty, so when the Jet drive was removed, the manual options still worked.

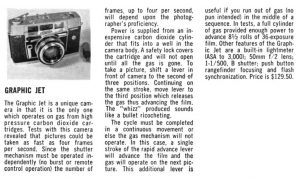

When it did go on sale, the camera sold for $129.50 which when adjusted for inflation, compares to about $1100 today making it quite an ambitious purchase for a product with such cutting edge technology. The short blurb to the right from the August/September 1962 issue of US Camera is the only one I’ve found with a reference to it’s price. I could not find any information about how much the replacement CO2 bottles cost.

Interestingly, this mini review is also the only one that suggests the camera could be fired at speeds as fast as 4 exposures per second. I am unsure if this was a mistake as all Graflex advertising material suggest a maximum speed of up to 2 exposures per second.

I also found it interesting to read that the sound of the camera firing resembled the sound of a bullet ricocheting as I’ve never seen or heard one of these cameras with a working Jet-O-Matic system.

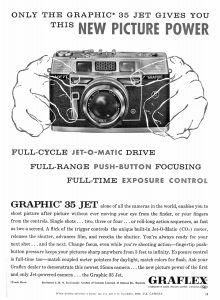

The two ads below appeared in US publications in late 1961 and early 1962 heavily promoting it’s “Jet Power!”.

The Graflex Graphic Jet would not only be Graflex’s last joint venture with Kowa, but it would also be their last 35mm camera. Production would continue of their press cameras, and in 1968, the company would be sold to the Singer Corporation before being liquidated in 1973, ending the history of Graflex and it’s cameras.

Today, the Graphic 35 Jet is a pretty obscure camera. I’ve only seen one or two ever sold on the big auction site and only through a random encounter with a large lot of cameras was I able to get the one used in this review. I would guess that most collectors might find the Jet’s unique looks and feature set to be appealing, but there were so few sold, they are probably quite difficult to find. Establishing a value on a little known camera is difficult, as they show up for sale so infrequently that people likely don’t pay much for them. Still, this is a neat camera that was the result of a little known collaboration between Graflex and Kowa that might be worth adding to your collection.

My Thoughts

Ha! A jet powered camera?! Sign me up!

Ok, so it’s not actually powered by a jet and it uses CO2 bottles? That’s still pretty cool, I still want one.

How about one that is still called the Jet, but the “jet” feature has been neutered out of the camera and it only works manually? Well, I guess it still looks pretty cool and would make for a cool article. I guess I’ll keep my eye out for one that’s cheap enough.

The above fictional conversation describes my journey from when I first learned of this camera’s existence to when I acquired the one for this review. Certainly it would have been cool to have one in which the Jet Powered system was still in tact, but I likely would have not been able to find any way of using it as the bottles were discontinued over half a century ago, and even if somehow I was able to retrofit some kind of modern solution, the o-rings that were needed to maintain the pressure would have likely rotted out ages ago, so having to use the camera manually is hardly a problem.

Upon receiving the camera, I discovered the Graphic 35 Jet is quite large and heavy. Even without the parts needed to make the CO2 system work, the camera comes in at 796 grams. I’ve never handled a working CO2 model, but with the extra parts, plus a full bottle, I can see the total weight of the camera easily passing 900 grams and creeping toward 1000 grams.

The camera also features quite a few sharp corners and edges to it’s design which does it no favors in terms of it’s size. Soft and rounded corners can sometimes mask the weight of a heavy camera as it makes it easier to hold. In terms of size, weight, and styling, the only other camera that comes to mind is the Anscomark M.

Both the Anscomark and Graphic 35 Jet were Japanese 35mm rangefinder cameras, built specifically for a US company in the early 1960s and have large and heavy metal bodies, with sharp edges and some curious ergonomic decisions.

The camera has a solid feel in your hands and seems to be well made, but the finish on the metal parts of the camera have a dull, raw finish that give it a somewhat ‘low rent’ feel. It’s not bad looking, but I think that with more rounded edges and a shinier finish, the camera might have better attracted the higher end buyer that they were probably hoping for.

The top plate of the camera features the match needle meter window on the left, immediately next to the ASA film speed dial. The match needle system uses a meter coupled to the selenium meter and a diamond shaped pointer coupled to the camera. When the meter needle appears within the diamond, you have the correct exposure.

In the center is an accessory shoe, a manually resetting exposure counter, threaded cable release socket, and then finally a combined rapid advance lever with film reminder dial on top.

On the stepped plate immediately above the lens is a clever focusing scale that Graflex used on their other Graphic 35 cameras. This scale serves three purposes. The most obvious is that it displays the currently selected focus distance as determined by the two focusing paddles. The second, is that using the f/stop numbers above it, you get a depth of field scale. The final, which Graflex called the Spectramatic System, was for flash photography and matched colors to different types of flashbulbs which would then tell you what the ideal distance would be for proper exposure. I never attempted to use a flash with this camera, so I didn’t spend much time trying to figure it out.

With the door shut, the only thing you see on the back of the camera is the rear eyepiece window. There are no other settings or controls anywhere on the back plate or the door.

The bottom of the camera is perhaps it’s most interesting side as this is where the CO2 bottles would be installed on non-neutered models like this one. The large blank circular plate would have normally been where a circular cap would go for the CO2 compartment. The smaller, second blank circular plate beneath the 1/4″ threaded tripod socket is where a pressure release valve would have been, which was used to release remaining pressure in the camera before installing a fresh CO2 bottle. Since my example lacked these parts, and even if it hadn’t finding a usable bottle would have been nearly impossible, I could only read about the process for changing a bottle on page 24 of the Graphic 35 Jet’s user manual.

The rest of the bottom plate is where you’ll find the rewind clutch release for rewinding film, rewind lever, and the film door release button.

The film compartment is a bit wider than one found in most 35mm cameras, since there is a void next to the film gate to accommodate the CO2 bottle compartment within the camera. Film transport is from left to right onto a single slotted and fixed take up spool. The inside of the film door has a pressure plate with divots and a roller to help decrease resistance while film travels through the camera.

Second to the Jet-Powered namesake of the camera, the Graphic 35 Jet’s second most interesting feature is the moving focal plane that can be seen within the film compartment.

Unlike the earlier Graflex Graphic 35 cameras that used focus paddles in which the shutter and lens standard move forward and back depending on chosen focus, on the Graphic 35 Jet, the lens and shutter remain fixed, but the focal plane moves with the focus paddles. This in essence, pushes the film away from the lens at minimum focus and brings it parallel to the rest of the film plane at infinity.

In the image to the left, the top half shows the camera focused to infinity, and the bottom shows the camera at minimum focus. I can’t for the life of me see an advantage to this compared to every other camera ever made, and I wonder if this could have a side effect of scratching the film as it bends at minimum focus, but I guess if you want to make a “Jet Powered” camera as complicated as possible, this is one way.

Focusing the camera is done with the two paddles which are near the 10 o’clock and 2 o’clock positions around the lens. Pressing the left paddle focuses towards minimum focus and pressing the right paddle focuses toward infinity.

Beneath these paddles is what one might guess is a self timer, but is in fact the shutter release. With the camera to your eye and the photographer’s right index finger on the right focus paddle, the photographer’s middle and ring fingers can easily locate the lever on the shutter release. Pulling the shutter release lever towards the outer edge of the camera fires the shutter. Without a working CO2 system, the shutter release has only two positions. One with it at rest, and the other which fires the shutter. With a working CO2 system, the shutter release has three positions. One for rest, a middle position for firing the shutter, and a third for advancing the film and cocking the shutter. The Graphic 35 Jet is not capable of firing the shutter continuously, but with a rapid movement of the shutter release between the second and third positions, as many as 2 frames per second is possible.

On the side of the shutter near the 4 o’clock position is a small lever for selecting either M or X flash sync with the PC flash connection on the front of the camera. Not shown, but opposite the M/X lever near the 8 o’clock position is a lever for the self-timer.

The viewfinder for the Graphic 35 Jet is rather ordinary for a early 1960s 35mm rangefinder. On this particular example, there was a bit of haze that reduced the contrast for the square rangefinder patch, but had it been in pristine condition, it likely wouldn’t have been much different from other cameras of it’s era. The viewfinder is reasonably bright and features non-parallax corrected 50mm frame lines. There is no meter readout or any other exposure information here.

The Graflex Graphic 35 Jet is a really unique camera in many ways. It’s appearance is your first hint that this camera has something different about it. It’s Jet-O-Matic film advance system and push button focus with moving focal plane are two very interesting solutions to functions of the camera that many other companies had already answered. Describing a camera as “unique” isn’t always a good thing however, so which unique is the Graphic 35 Jet?

My Results

For the first roll through the Graphic 35 Jet, I chose an expired roll of Kodak Gold 200. I generally don’t like shooting this film as a first roll in an unknown camera, but I have so much of it, I decided to break my own rule. It seems that whenever someone in my personal life finds out I like old cameras, they inevitably have some 35mm point and shoot with a roll of two of Kodak Gold 200 in the bag. I’m never one to turn away free film and sometimes you can get some really terrific results from expired film so I thought what the hell, lets try it in this camera.

The old Kodak film showed some degradation near the edges, but otherwise still had faithful colors throughout most of the images. These images were exposed using Sunny 16 and shot for 100 speed film so I gave it an extra stop of exposure and I think it did OK. At least good enough to predict how this camera might have fared when it was new.

For starters, the 6-element Optar lens is quite good. At f/2 it is marginally slower than an f/1.7 or f/1.8 would be on another camera, but I so rarely shoot cameras wide open anyway, it made no difference to me. I assume this is a Kowa design whcih is a good thing as I constantly get excellent results from cameras with Kowa lenses.

Sharpness is excellent from corner to corner and the images show no optical anomalies associated with lesser lenses. There does appear to be a tiny bit of haze in some of the images, especially those showing the sky which to be honest, I didn’t notice when I initially inspected the camera, but it’s hardly a deal breaker. In hindsight, some contrasty black and white might have been a better pairing for this camera if I were to shoot it again. Notice I said “if”.

I love quirky cameras. I really enjoy seeing some of the off the wall ideas that were implemented over the years that for one reason or another, weren’t continued beyond a couple of models. From left handed controls to clockwork wind up motorized film transports, there is no shortage of oddities in this hobby.

The Graphic Jet 35’s CO2 powered film advance might take the cake for the most off the wall idea. Even though this particular example was a later one after they gave up on the concept and neutered the CO2 parts out of the camera, enough is still there to get an idea of what it might have been like when it was new, and I can tell you, this camera sucks to use.

I was surprised when I put it on my kitchen scale and it came in under 800 grams as the camera feels heavier than that. It’s quite large and has sharply contoured edges. Compared to the Anscomark M, which is another Japanese made 1960s 35mm rangefinder with sharp edges, the Graphic Jet 35 seems to have edges and angles in all the wrong spots.

The ergonomics of this camera aren’t good. I like the idea of the push button focus with a moving focal plane, but the execution doesn’t work as going from minimum focus to infinity requires a movement of only a few millimetres. It was very difficult to precisely focus, and I would often forget which button did what which slowed me down on many occasions as I would go in the wrong direction, only to have to press the other side to move it to where it needed to be.

The shutter release is easy to operate and doesn’t require much force, but is in such a strange location, I could just never get used to it. Even though I only shot a single roll of film in this camera, it felt like quite a bit more. Finishing that roll seemed like a burden for me as the controls were so unfamiliar to me and the ergonomics so poor that I couldn’t wait to be done with it.

I won’t fault the camera for a slightly hazy viewfinder and maybe even a tiny bit of haze in the lens as that wouldn’t have been there when the camera was new, but CO2 “Jet Power” or not, if I was in the market for a new and innovative 35mm rangefinder when this camera first went on sale, I would have immediately given it back to the salesperson the first chance I had to handle one.

Am I overreacting? Maybe a bit, but for me, to enjoy a quirky camera, it still has to perform it’s intended function reasonably well, and I just can’t say that for this camera. It certainly is neat looking and the idea is cool, but boy does it suck to use.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

https://graflexcamera.tumblr.com/post/127247512106/graphic-35-jet

http://phsc.ca/camera/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/GJ3-16.pdf

I have one of these, also without the CO2 system. It’s a fun camera to shoot, I like the location of the shutter release. On mine the selenium meter is still accurate. I’d probably use it regularly if it wasn’t such a rarity.

This one of the cameras on my “want” list in the category of “what were they thinking when they designed this”. Sadly, I have yet to see one at a reasonable price that wasn’t in wretched condition. Thanks for confirming my impressions of this camera that I had only read about.

Great post, love the idea of this camera..oh to see one with the jet working would be amazing. I think it the most unusual camera I have read about.

Yeah, hearing that “ricochet” sound would be something. I guess it could be possible to find a “non-neutered” one, and have it rebuilt with new seals and then find a way to adapt a CO2 bottle from an air rifle to make it work, but that would seem like an awful lot of work! I definitely agree this camera is unusual, I just wish that translated into a fun shooting experience, which it did not!

The cartridges for soda siphons that are readily available appear to be identical to the ones for Graphic Jet.

Edwin, I would be cursing you right now if I had a Graphic 35 Jet that wasn’t neutered, so even if I found one, it still wouldn’t work, but this is good information for someone else who stumbles upon this review that has one that’s still in tact. Thanks for sharing!

Thank you for the detailed write-up. I was very interested in getting one of these, and I still might, but the GAS has abated a little thanks to you

I often say I am always happy to help people spend their money, but the opposite is also true, if something I write saves someone from having to buy something they might not like, that’s good too!

After graduating from RPI in 1958 my first engineering job was at Graflex in their relatively new facility at 3750 Monroe Ave. in Pittsford, NY near Rochester. I was hired by Chief Engineer Bill Sanderson and worked for Hans Padelt who was the principal engineer on the Graphic 35 Jet camera. I worked specifically on the CO2 powered mechanism. At the time we were testing different materials for the operating piston, eventually choosing Delrin over Nylon. I still have a number of piston samples. This piston had a gear rack on one side that engaged with a pinion which coupled the rotational motion to the camera mechanism. I also worked on refinements to the high pressure valve which admitted pulses of CO2 to the cylinder. Teflon was selected as the zero leakage valve seat material for the tiny brass metering valve.

The CO2 cylinder tip was pierced as the endcap was screwed into the CO2 chamber in the mechanism. That meant that the chamber, not the cartridge, had to withstand the CO2 vapor pressure. We estimated the camera might reach a temperature of 180 degrees F if left in the sun on a hot summer day. At that temperature the pressure would reach 1250 psi. The calculated strength of the pressure chamber was well above that, but to verify I tested sample chambers at temperatures of over 400 degrees F. In use the pressure chamber was soldered into the mechanism. At 361 degrees F the pressure would reach 1608 psi but would go no higher because the solder would melt releasing the pressure. It’s likely the O-ring sealing the endcap would have failed as well.

Although Graflex advertised that the camera could take 2 pictures a second, I have operated one at closer to the 4 per second rate mentioned elsewhere. In late July, 1961 I was part of a team that entered a scale model of a four engine C-54 military cargo plane in the National Model Aviation competition at Willow Grove Naval Air Station near Philadelphia. After over a year of construction I wanted to have the best record possible of the model’s flight, so I borrowed a Graphic 35 Jet from Graflex. My wife agreed to act as photographer and I was hoping she would capture the event in a rapid sequence of pictures. Unfortunately, the aborted flight lasted only about 10 seconds and she was so excited she never once tripped the shutter.

While I do not have a 35 Jet camera, I do have a mechanism assembly that is in excellent working condition. It weighs 152.3 grams without the 32.6 gram cartridge.

John Gardner

Oh, sorry. Mixed up the spelling. Graflex Graphic 35 Jet.

Thank you for this post. I love the history behind this funky old camera.

Hi there. I have a Graphlex Graphic 35 jet. Neutered. It does need repair, but it really doesn’t look too bad. It’s a charming old thing. I’m tempted to find out if someone can repair it.

One of these was on Shopgoodwill a few months ago. As part of an auction lot. There was only one photo that did not show the bottom of the camera. It was going cheap so I put in a low bid and got it. Turns out it’s an intact example that still has the CO2 system . I’m halfway through a test roll to see how the rest of the camera works. If it’s working ok I may try it with a CO2 cartridge next, although I suspect the seals will leak a bit.