It’s been two years since the photography world lost one of it’s most important photographers. David Douglas Duncan, then 102 years old, passed away peacefully on July 7, 2018 with his wife by his side.

Duncan was a life long photographer who later became good friends with Pablo Picasso, photographing him a number of times.

Originally developing his skills as a photographer in deep sea photography, he won a national prize in 1937 with the image to the right shot with a folding Kodak which encouraged him to keep shooting. With his winnings he bought better equipment, first a Universal Mercury and later a Rolleiflex.

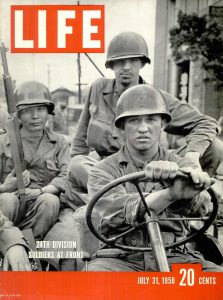

His work has appeared in National Geographic, LIFE Magazine, for ABC News, and in a variety of other publications. Although shooting a huge number of subjects, it was his work as a wartime photographer, first during the Korean War and later in Vietnam which earned him the most notoriety.

Back in June 2018 shortly after his death, I published a sort of ‘in remembrance’ article in my Rotoloni Report series covering Duncan’s role in popularizing Nippon Kogaku lenses, and later serving as sort of a spokesperson for Nikon.

David Douglas Duncan’s influence on the success for Nippon Kogaku was significant, and had a chance encounter with Japanese photographer Jun Miki not occurred, it’s possible that the Korean War would have started without anyone ever learning of the optical superiority of what was then an unheard of Japanese company.

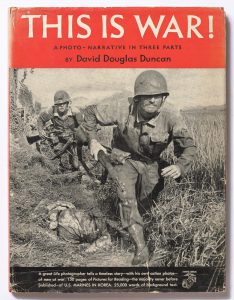

Much has been written about Duncan’s wartime photography and his role in helping to discover Nikon in the early 1950s, but this week’s Keppler’s Vault brings you two articles, the first which appeared in the March 1951 issue of Modern Photography, and the second from LIFE Magazine’s July 31, 1950 issue, barely a month after the Korean War had begun. The stories and photos in these articles pre-date any success Duncan brought to Nikon, before his book “This is War!” was published, and before most anyone outside of photojournalism circles had even heard of David Douglas Duncan.

Author Bruce Downes introduces Duncan as the ideal all-around war correspondent, saying that whatever story his excellent photographs couldn’t communicate, his written words could, and vice versa. Duncan was young, energetic, and most importantly, had three years experience as a photographer with the US Marines in the South Pacific during World War II and prior to that as a freelance deep sea photographer. Duncan’s time with the Marines taught him survival tips which allowed him close access to the men and women on the front lines. He had a high level of defensive awareness that kept him alive by anticipating enemy attacks.

When war broke out in Korea in June 1950, Duncan was working in Tokyo shooting peace time photos, and because of his experience, was one of the first photographers assigned to cover the new conflict. At the age of 34 years old, Duncan was already a grizzled veteran and knew the challenges of a foot solder as he had been one himself. Although the article doesn’t specifically say this, it is implied that his experience helped him relate to the soldiers he would photograph, helping gain their trust in ways that other photographer’s might not have.

My favorite part of the article starts on the article’s sixth page (originally page 47) where it talks about his gear. One of Duncan’s secrets was to carry as little of equipment as possible, including his camera. During World War II, Duncan used a Rolleiflex TLR, but had switched to a 35mm Leica. In a chance encounter that I described in my earlier David Douglas Duncan article, after taking a tour of Nippon Kogaku’s nearby factory in Tokyo, he was so impressed with their quality, he exclusively used screw mount Nikkor lenses mounted to two different Leica IIIcs to shoot the Korean War. The lenses he used were the 50mm f/1.5, 85mm f/2, and 135mm f/3.5 Nikkors. True to their reputation as being sharper than any other out there, when Duncan began sending his negatives back to LIFE Magazine’s labs in New York, they were amazed at the resolution of the images.

Interestingly, but not out of context for the time, the Modem Photography article refers to the makers of the Nikkor lenses as “Japan Optical Co. Ltd.” which is the literal English translation for Nippon Kogaku Kogyo Kabushikigaisha.

While shooting, Duncan carried only the essentials to survive. In addition to his two Leicas and three Nikkor lenses, he filled his pockets with about two weeks worth of film and the same Weston Master exposure meter that he used during World War II. Duncan had a good eye for exposure when the light was good, but took the time to use his Weston meter when it wasn’t. It was these best practices that earned Duncan a positive reputation back home with LIFE’s lab techs because his negatives were said to be the most consistent of any photographer submitting film.

As if having to survive in a battlefield staying alive and having to find worthwhile things to photograph wasn’t already hard enough, in those days, the photographer also had to take notes on each exposure he took and for that Duncan carried a small brown notebook with pages numbered 1 through 36, one for each exposure. The locations and names of people in the images had to be included and spelled correctly as they were the only way the editors back home would have any idea of what was happening, or who was in the images. After sending his film back on a plane to New York every Friday, the next time Duncan would see his own images would be when they were published, so accuracy was critical.

As mentioned earlier, Duncan’s knack for the written word helped elevate his photography even farther, and near the end of the article, Downes recites a couple paragraphs worth of Duncan’s narration aboard a jet fighter during a firefight above North Korea. This description, along with his photographs are said to be the first ever made by a magazine photographer in actual combat.

Today, David Douglas Duncan needs no introduction as his legacy is one of the greatest of any photographer, but in March 1951 when readers first read the Modern Photography article, many were getting their first glimpse into someone who would define war photography. I can only imagine the sense of awe these readers must have experienced reading this story, and much like them, even with the benefit of knowing who Duncan was, I felt a similar level of awe in what he accomplished.

It’s been two years since Duncan passed away and quite a bit longer since his last war time photograph, but with his life’s worth of work and articles like this, he will never be forgotten.

If you would like to learn more about many of the pictures in this article, plus several that aren’t, check out this photo essay which first appeared on LIFE magazine’s website.

For an added bonus, here is another original article, first published in the September 15, 1950 issue of LIFE Magazine, nearly a year before his book of the same name was published.

All scans used with permission by Marc Bergman, 2020.

Amazing to hear of people like this — a photographer and photo-journalist yes, but he enlisted in the Marines after Pearl Harbor — to fight, not as a photojournalist (he could have applied to be an embedded photographer even then, without having to join the military or carry a gun). So he felt strongly enough about the war to enlist, yet he wanted to document what he saw — and continued with that even after his military career. Wow. And great pics for a rangefinder (OK, a Leica with the best lenses!), handheld light meter and film stuffed in his pockets.

This is a most interesting profile. Now may I suggest you present Roy Stryker’s remarkable group of photographers and their work for the FSA and the Pittsburgh Photographic Library. His shooters included Carl Mydans, Walker Evans, Gordon Parks, Clyde Hare, Harold Corsini, and the great but now forgotten Esther Bubley. I’d wager that few of our new analog shooters have heard of these folks, let alone seen any of their monumental work.