This is a Konica Auto-Reflex, a 35mm SLR camera produced by Konica of Japan starting in 1965. This model was the first in Konica’s long lived Autoreflex series and is the only one with a hyphenated name. It is also the only model that can seamlessly switch between shooting full frame and half frame 18mm x 24mm shots without changing rolls. The Auto-Reflex was also the first mass produced focal plane 35mm SLR to feature Automatic Exposure which was accomplished via a body mounted CdS exposure meter offering shutter priority auto exposure. Konica went all in on this camera, not only building it to an incredibly high quality standard, but also offering as much cutting edge technology available at the time of it’s release.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

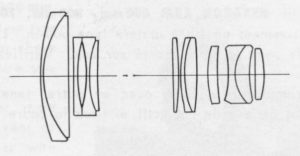

Lens: 57mm f/1.4 Konica Hexanon coated 6-elements

Lens Mount: Konica AR Bayonet

Focus: 1.5 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Fixed SLR Pentaprism with Microprism Circle and Ground Glass Focus Aides

Shutter: Copal Square Vertically Traveling Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: Coupled CdS Cell w/ viewfinder readout and Shutter Priority AE

Battery: 1.35v PX675 Mercury

Flash Mount: M and X Flash Sync

Weight: 998 grams (w/ lens), 716 (body only)

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/konica/konica_auto-reflex.pdf

Lens Brochure: https://www.cameramanuals.org/lenses/konica_hexanon_lenses.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Konica Auto-Reflex is a very solid and capable camera that compares favorably to the best SLRs of the 1960s, but tops them all with a unique feature no other SLR had or ever would have, which is the ability to switch between full and half frame images in the middle of a roll. This gives the Auto-Reflex the distinction as a ‘one of a kind’ camera that is worth seeking out for this one feature. Regardless of how you shoot it however, you will undoubtedly be happy with his all metal mechanical build. auto exposure system, and excellent lenses. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 20% | |

| Bonus | +1 for unique ability to seamlessly switch between full and half frame | ||||||

| Final Score | 11.8 | ||||||

History

The name Konica is used today in a variety of business applications, making products such as printers, photo copiers, and other imaging related technologies. The company that in 1965 produced this Auto-Reflex SLR no longer exists and as of 2006, exited the photographic and camera industry.

The original Konica had a long and prosperous history as the oldest Japanese camera maker. Konica could trace it’s roots all the way back to a man named Sugiura Rokusaburo who in 1873 sold pharmacy supplies in Tokyo, Japan. Sugiura launched his own pharmacy company, named Konishi Honten in 1878. In 1882, the company began producing it’s own photographic materials and selling them to other Japanese companies. Twenty years later, Konishi sold the Cherry Portable Camera, which was the very first Japanese made consumer camera.

Over the next 2 decades, Konishi Honten did very well, and in 1921 was renamed G.K. Konishiroku Honten. The company continued to be successful throughout the 1920s, releasing several other lines of cameras and even founded the Konishi College of Photography in 1923. In 1931, the company released the first ever commercially available Japanese camera lens, known as the Hexar.

Between the years of 1936 and 1943, as Japan became increasingly involved in World War II, the company’s business became reorganized and the name changed several times. At one point their entire retail and wholesale business was stopped.

After the war, the Japanese company hoped to expand their sales outside of Japan, so their name was changed once again to incorporate English, and now they were known as Konishiroku Photo Industry Co., Ltd. In 1947, the company released their first 35mm rangefinder camera, known simply as the “Konica”.

In the years after the war, many Japanese companies struggled to succeed outside of their home country as the world was not ready to put trust in Japanese made products but with Konishiroku’s strict attention to quality control and positive reputation, they eventually saw themselves in the forefront of the photographic world.

Throughout the 1950s, Konishiroku continually improved their 35mm models, even dabbling in other segments such as Twin Lens Reflexes like the Koniflex, and professional 6×7 medium format cameras like the Koni-Omega system, but like most camera makers, by the late 1950s demand was quickly growing for 35mm Single Lens Reflex cameras like the Japanese made Asahi Pentax and Miranda SLRs.

At the Tokyo International Trade Show in May 1959, Konishiroku would announce their new 35mm SLR prototype, called the Konica Flex. Based on an industry average two to three year development cycle of an all new SLR, work likely began on this camera sometime in 1956 – 57.

The new camera would have an ambitious list of features, including a coupled selenium exposure meter (behind a door on the front of the prism) with match needle visible in the viewfinder, a fixed pentaprism with split image focus aide with Fresnel pattern for improved brightness, instant return mirror, automatic diaphragm, a metal focal plane shutter with speeds from 1 to 1/2000 and electronic flash synchronization at 1/125, a unique film pressure plate that relieves pressure off the film while advancing the film in an attempt to avoid scratching the film, self timer, and an all new bayonet lens mount with new Hexanon 7-element 50mm f/1.4 lens as standard.

Nine months later, in February 1960, the new SLR, now called the Konica F was released into production, retaining nearly all of the same features as the Konica Flex prototype. The most obvious change was the removal of the hinged door over the selenium exposure meter, and a slight revision to the standard f/1.4 lens, now measured as 52mm instead of 50mm.

The Konica F is a bit of a mystery as there are a lot of questions surrounding it’s release. It is unclear why the name of the camera was changed to Konica F. Some have theorized that the name change was to avoid confusion with the company’s Koniflex TLR, but a more likely explanation was to follow the trend of giving reflex cameras a name with “Flex” in the title.

Another mystery of the Konica F was the camera’s shutter, which closely resembles the Copal Square vertically traveling shutter. Most sources online suggest the Nikkorex F from 1963 was the first camera to have this shutter, so to see it three years earlier in another camera seems unlikely. It’s possible that this shutter is an earlier variant of the Copal Square, developed jointly between Konishiroku and Copal, but this is just a guess.

Edit (9/24/2020): After posting this article, I was contacted by Konica enthusiast, Jean-Jacques Granas who runs the site konicafiles.com and filled in the blanks regarding the Konica F’s shutter.

The shutter in the Konica F was made in-house by Konishiroku after 7 years of design work and Copal had nothing to do with it. It worked, but it was delicate, highly complex, and expensive to produce and work on. This is the main reason why the Konica F cost so much. As the camera didn’t sell well, as you point out, Konica and Mamiya jointly decided to hire Copal to come up with a simpler, cheaper and more dependable design. Copal did so in 1963 (with the Copal Square). The Nikkorex F was indeed the first to have it and the reason was because Mamiya made that camera, not Nikon. The second was the Konica FS. The Copal shutter is significantly different than Konishiroku’s shutter (called Hi-Synchro). The two companies did not work together on the Copal Square, even if Copal doubtlessly benefited from the years of work Konishiroku put into developing its shutter.

Production of the Konica F was short lived, and accurate numbers were not kept, but the best estimates are that between 1500 to 1600 examples were made, a majority of which were exported to the United States. With a retail price in 1960 with case and 52mm f/1.4 lens of $395, which when adjusted for inflation compares to $3440, the camera was extraordinarily expensive, likely making it a tough sell to American photographers.

Perhaps realizing that the Konica F was too much camera for the market, in December 1960, a scaled down model called the Konica FS was released which eliminated the light meter and had an improved, but simplified shutter with a top 1/1000 shutter speed. Together with a 50mm f/2 Hexanon lens, the Konica FS sold for $205, nearly half that of the F.

Facing stiff competition from a variety of other Japanese and German camera makers with competing SLRs, it was clear that Konishiroku prioritized innovation, trying to push the limits of technology that could be included in their cameras. With models like the Konica FSW from 1962 that had one of the first implementations of a time and date data back, to the FM from 1964 with a body mounted CdS exposure meter, Konishiroku was always at the leading edge of new features.

Now with a couple years worth of experience making SLRs and increased brand recognition, Konishiroku decided it was time to aim for the fences with a new and innovative SLR. Starting in the late 1950s, “electric eye” cameras capable of automatic exposure became common in the entry level segment. Models like the Brownie Starmatic, Revere Eye-Matic 127, and AGFA Optima all offered this feature via a simple implementation in which a selenium exposure meter would automatically register an appropriate f/stop based on available light and with a single or limited speed shutter, the camera could automatically expose images without the need for an external light meter.

In 1965, when Konishiroku was about to reveal their next SLR, auto exposure cameras were until them limited to very basic cameras as the necessary technology to make it work was prohibitively complicated in an SLR with interchangeable lenses and a full range of shutter speeds. Never one to shy away from a challenge, the engineers at Konishiroku met the challenge with what would become the Konica Auto-Reflex

First released in December 1965, the Konica Auto-Reflex was the first successful focal plane 35mm SLR with automatic exposure. In Japan and Germany, the camera was sold under the name Konica Autorex, and Revue Auto-Reflex, respectively. In order to accommodate the necessary communication between the lens and the metering system in the camera body, a change was required to the Konica lens mount. An all new mount, which was internally referred to as the Konica Bayonet Mount II, but later called the Konica AR-mount, not only added the necessary linkages, but also increased the internal throat diameter from 40mm to 47mm, making it much more suited to faster lenses and heavier telephoto lenses.

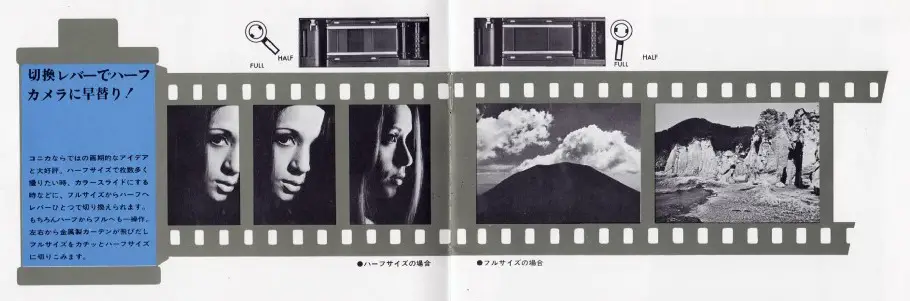

Automatic Exposure wasn’t the only trick up the Auto-Reflex’s sleeve, as the camera also was the first (and last) 35mm SLR to be able to shoot both 24mm x 36mm full frame exposures along with 18mm x 24mm half frame exposures on the same roll of film, with only the flip of a switch. When in half frame mode, a mask would move in from the sides of the film gate to make the half frame image, two reminder “teeth” would appear in the viewfinder to indicate a half frame, and the exposure counter would begin counting in half frames.

The Auto-Reflex was truly an innovative camera, featuring two features never before seen on a 35mm SLR, while also being built to the high quality standard that previous Konica SLRs were, and offering a complete lineup of quality Hexanon lenses.

When it first went on sale, the Konica Auto-Reflex didn’t quite reach the lofty prices of the original Konica F, but it was still expensive, with the 57mm f/1.4 lens and case, the camera cost $317.50, which when adjusted for inflation, compares to $2535 today. Prices would quickly drop however, as by 1968, the camera could be had with the f/1.4 and f/1.8 lens for $230 and $190.

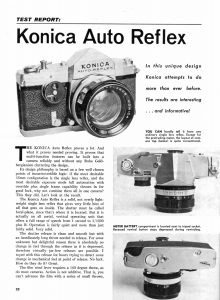

In the October/November 1966 issue of Camera 35 magazine, Arthur Kramer took a quick look at the Auto-Reflex, making several positive remarks both about the camera and the sharpness of the Hexanon 57/1.4 lens. In the final paragraph, Kramer comes away impressed at the build quality, usability, and features of the Auto-Reflex.

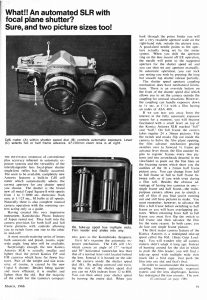

Edit 10/1/2020: I found another period review of the Auto-Reflex (actually, the Autorex), this time from the March 1966 issue of Modern Photography.

This sales brochure seen below was distributed to Konica dealers, and featured some of the accessories available for the Auto-Reflex including bellows and microscope attachments, and a variety of lens mount adapters, including one that allowed use of the earlier Konica F bayonet lenses. Perhaps the most interesting accessory was a 47-100mm zoom lens made specifically for use with the Auto-Reflex in half frame mode. I will cover this lens in more detail later in this article.

While the Auto-Reflex was a precision camera with excellent optics, it’s inclusion of auto exposure was seen as a detriment to professional photographers who at the time felt that automatic exposure was reserved for unskilled amateurs. In an effort to accommodate those who might not want AE and also to have a lower cost model, in March 1966 the Auto-Reflex P was released without the built in light meter and auto exposure features. Strangely, there was a clip on meter available for the P which added it back on.

Although the Auto-Reflex was an innovative camera loaded with features that appealed to many photographers upon it’s release, it came at a time when the entire industry was rapidly changing with new and exciting models coming out by nearly every company on a regular basis. In April 1968, the company now known as Konica, would release the Autoreflex T, an update to the original model, removing the half frame option, but offering through the lens metering via twin CdS cells within the viewfinder.

Konica would continue releasing new models in the Autoreflex (no hyphen) series through the Autoreflex T4 in 1977 eventually concluding with the release of the motorized drive Konica TC-X in April 1985. Three years later in 1988, Konica would completely exit the SLR business.

Today, the Konica Auto-Reflex is a very popular camera for collectors and users alike. In addition to it being made to a high quality standard, it is the only 35mm SLR and one of very few of any kind that can shoot both full and half frame images on the same roll. Konica would continue to produce lenses with the AR bayonet mount until the 1980s so there’s a wide variety to choose from making this an very adaptable camera. The hardest part about find one is that they were only produced for about 3 years, and later Autoreflexes lost the half frame option, making this a relatively difficult camera to find.

Konica Hexanon Zoom 24×18 47-100mm f/3.5

After I had shot the Auto-Reflex a number of times in preparation for this review, my friend Anthony Rue mentioned he had this unique half frame specific zoom lens for the Auto-Reflex and asked if I wanted to borrow it. Of course, I told him! With another lens to shoot, the review was delayed so I could spend some time with it, and I am glad I did.

The Konica Hexanon Zoom is very curious as it’s the only zoom lens I know of that was designed specifically for a half frame SLR. Perhaps Olympus had one for the Pen SLR, but this lens also covers full frame too, albeit with some vignetting, making for a focal length of approximately 66-140mm.

The 13-element lens is very well constructed, long, and quite heavy. Weighing 430 grams by itself, when mounted to the camera, the combo is a portly 1146 grams, 148 grams heavier than with the 57mm f/1.4 lens.

It is a one-touch lens in which a large grip is rotated for focus and pushed and pulled to zoom. Minimum focus is rather long at 7 feet making this lens good for portraits and landscapes, but not closeups. I quite like one touch zooms as it prevents me from having to relocate my hand for both functions, but some photographers do not like them as they find that small changes to the zoom can also throw off the focus.

With a relatively slow f/3.5 maximum aperture, the viewfinder is darker with the lens installed, making indoor shots a challenge. In addition, the slow speed of the lens can also cause the microprism focusing aide to darken too much, making focusing a challenge.

Image quality was good on film, but I regret not having an AR to Fuji X-mount adapter to shoot it digitally and do some pixel peeping, but if there’s one thing I’ve learned about lenses, is that when you see the word “Hexanon” it’s going to be good.

This is a cool and rather rare lens. It is unique in that it was purpose built for this one camera and although it would mount to other Konica Autoreflexes, you’ll always have vignetting in every image, so unless that’s a specific look you’re going for, you’ll want to keep this lens for the camera it was built for.

My Thoughts

I don’t think you’d need to try very hard to convince anyone into old cameras to want to try a 35mm SLR that can shoot both 24mm x 36mm full frame and 18mm x 24mm half frame images on the same roll, in the same camera, all with just a flick of a switch.

The Konica Auto-Reflex is one that had been on my radar for quite some time before finding one for a very reasonable price late last year. Thankfully with this example, came the Hexanon 57mm f/1.4 lens in all of it’s glory. I prepared for the camera’s arrival by reading as much about it as I could online and many reviews touted the camera’s size and heft as an asset, saying this was a glorious hunk of metal and glass, built to the highest standards of 1960s craftsmanship.

Upon it’s arrival, I never doubted the camera’s quality as it felt every bit as solid as I had expected, but it wasn’t as heavy as I thought it would be. At a weight of 716 grams without a lens, the body is nearly identical in weight to that of a Minolta SRT-101 and a good 25 grams lighter than a period correct Exakta VX1000. By no means is this a light weight camera, but I was fully expecting a neck braking block of adamantium and kryptonite.

The top plate has controls in the usual locations, but presented in a way that doesn’t really look like many other 1960s SLRs. For starters, the folding rewind crank is at the extreme edge of the top plate. It tucks into the body when not in use much like that of the Canon 7 rangefinder. In use, it works the same as you would expect any other camera to, but is a nice touch.

Next, on the left diagonal side of the pentaprism is a plastic frosted window which lets natural light to illuminate the meter readout within the viewfinder. This is a very nice touch that differs from other cameras in which the meter reading takes light from within the lens. This means that if the lens is stopped down, dimming the main viewfinder, you will always have an easy to read meter readout…assuming there’s light coming from above you. In dark rooms where your light source is ahead of you, you might have the opposite problem where the image within the viewfinder is bright, but the meter readout is impossible to see. I can’t say whether this method is better or worse, but it is different.

Next is the toggle switch for Full frame and Half frame shots. Moving this switch does a couple different things. The most obvious is that two little flaps move into position in the film gate, blocking off the sides of the full frame image, reducing the width from 36mm to 18mm. Second, is that two little “fingers” drop down from the top of the viewfinder image to remind you that you should only compose between those two fingers, but also, the winding mechanism changes to only advance the film and exposure counter half as much in half frame mode.

Although this can be done at any point in the middle of a roll of film, there is a specific order that you must remember for doing this, so as not to overlap images.

Finally, we have the automatic resetting exposure counter, cable threaded shutter release button, and rapid wind film advance lever. Like most film levers of the era, movement of the lever is tight, but not too tight, and has an offset of about 30 degrees before film advancement occurs.

In front of the shutter release is a round dial that doubles as both the shutter and film speed selectors, and the housing for the body mounted CdS exposure meter. This location is a curious one for the shutter speed dial, but in use works fine. Perhaps keeping the mechanics of the shutter and film speed selectors so close to the meter simplified the design and made it work better.

You’ll notice that opposite of the CdS meter window is a small button marked Override. It wasn’t obvious to me at first what this does, but after reading the manual, it appears the camera has a lock which will prevent you from selecting shutter speeds outside of the range of the meter when the camera is in auto exposure mode. When this happens, if you still want to force a speed outside the range, an upward press of this Override button will allow that.

On the camera’s bottom, we have the rewind release button, centrally located 1/4″ tripod socket, battery compartment for the PX675 Mercury battery, and the door release latch for the film compartment.

The film door is hinged on the right, and other than seeing the gates deployed for half frame images, we see a rather ordinary 35mm film compartment. Film travels from left to right onto a multi-slotted fixed take up spool. Since the rewind knob and handle are offset from the cassette fork, there is no way to pull up on the fork when loading or unloading the cassette, so there is a curved opening on the camera’s bottom plate to aide in loading the cassette. The film pressure plate is very large and dimpled, which helps maintain flatness and reduce friction as film passes across it during transport.

With the door closed there is the circular eye piece and the meter on/off switch which also doubles as a battery check. In the check position, the meter needle in the viewfinder will swing to a mark near the f/8 position on the scale. The operation of this meter switch is one of my few nitpicks to the camera as forgetting to turn the meter off and draining the battery after you’re done shooting is very easy to do.

Up front, we see what was at the time Konica’s new AR lens mount which was much larger than the original bayonet mount from the Konica F. The lens is released by a sliding button near the 5 o’clock position around the mount. A depth of field preview button is near the 7 o’clock position, and a mechanical 10 second self timer is to the left of that button.

The viewfinder is large and compared to other mid 1960s SLRs, is bright enough for all outdoor work. Comparing it to SLRs that came a few years later, when lenses slower than f/2 are used, things get dark quickly. Wearing prescription glasses, I had no issue seeing all four corners plus the exposure scale on the right which is illuminated via a plastic window on the side of the pentaprism. Whether you have the camera in full of half frame modes, two vertical lines showing the 18x24mm frame are always visible, but only in half frame mode, will two triangular fingers drop down from the top to remind you to only compose your image within those lines.

When looked at as a whole, the Konica Auto-Reflex is a heck of a classic camera. Even without the switchable full and half frame modes, this is a quality built camera with a nice viewfinder, a good metering system, and support for excellent lenses that would have made for a compelling camera to shoot. With that feature however, the Auto-Reflex is in a class of it’s own. But how is it to shoot?

My Results

Expecting this to be a camera I would use regularly even after writing this review, I loaded up several rolls of film in the Konica Auto-Reflex. With each roll, I would shoot some images full frame and some half frame. I didn’t specifically look for shots that would be ideally suited to full or half frame, I more or less just did it to get a feel for how it worked. Of the four rolls of film represented below, the two color rolls are both Fuji 200 and the two black and white rolls are expired rolls of Kodak Panatomic-X 32 and Kodak Tri-X 400.

I separated the galleries between the full frame and the half frame shots. This first gallery is all of the full frame exposures.

This second gallery is of all the images I shot half frame. Although I did have access to the special half frame 47-100 f/3.5 zoom lens, I did not use it for any of these images. I honestly don’t believe that other than having the option of a variable focal length, that you would have noticed any difference in these images had I used it.

The Konica Auto-Reflex is an exceedingly enjoyable camera to use. Having the flexibility to switch between half and full frame is the camera’s best feature as it allows for some interesting creative effects, or could help extend a roll of film that you’re nearing the end of and want to conserve exposures with. I’ll admit to not getting super creative with my use of the half frame shots, but in the hands of more capable photographers, this could be a game changer for them.

As a full frame 35mm SLR camera, the Auto-Reflex is very well built and compares favorably to all other A-List Japanese and German manufacturers of the day, even Nikon. At just under 1000 grams with a lens mounted, the camera is solid, but not uncomfortably heavy. All of the camera’s critical controls are in ergonomically logical positions. The film advance lever moves with just the right amount of tension so as not to be difficult, while also not feeling flimsy.

I had access to three lenses, the 57mm f/1.4, 35mm f/2.8, and 47-100mm half-frame Zoom and they all performed well optically. The focus and zoom movements were nicely dampened and despite being over half a century old, still had lubrication that had not yet hardened.

If there was one area in which the Auto-Reflex was not perfect, it’s the viewfinder. Using an etched ground glass with a Fresnel pattern, the viewfinder was very bright with the f/1.4 lens mounted, but with both the wide angle and zoom lenses with max apertures of f/2.8 and f/3.5, the image darkened quickly, making indoor and low light photography a challenge. In several instances where I used this camera indoors, I missed focus, despite having experience with many other 1960s SLRs. My personal preference of split image rangefinders over microprism circles likely would have improved things a bit.

Don’t get me wrong, the viewfinder is still very good, and with the separately illuminated aperture scale, it’s very easy to see your meter reading in all but the worst light, but of course I have the benefit of hindsight knowing how great things would eventually get, but photographers in 1966 likely wouldn’t have had anything to complain about.

You’ll notice that I haven’t once mentioned the lack of TTL metering as a con to this camera. Like I mentioned in my review for the Leitz Leicaflex, which was another 1960s camera with a body mounted meter, not having the exposure meter inside of the camera isn’t really as big of a problem as some people make it out to be. Sure, there’s going to be some really specific situations where a through the lens meter is better than a body mounted one, but for 95% of general photography, the accuracy of the meter is of far greater importance than it’s location.

Although it wasn’t perfect, I really enjoyed shooting the Auto-Reflex. It’s a gorgeous camera that despite being large and heavy, has excellent balance and near perfect ergonomics. Konica’s Hexanon lenses are as good as the best Japanese lens makers of the day, so you’re always bound to get some outstanding images.

I suspect a large number of people (myself included) are attracted to this camera because of the switchable half-frame mode, I feel as though that even if it didn’t have that mode, the Konica Auto-Reflex would still be a great camera. As a full frame camera, the Auto-Reflex is excellent, which perhaps is why Konica omitted the feature on all future SLRs. I won’t go as far as to call the half-frame mode a gimmick, but while shooting with the camera, I can’t honestly say that switching back and forth made the experience any better. If you specifically need a half frame SLR, you might be better off with an Olympus Pen SLR as they’re quite a bit smaller and not nearly as heavy.

The Konica Auto-Reflex may be the ultimate fully mechanical 35mm SLR. It can be used entirely without a battery, or with a battery you get Shutter Priority AE. You can have your choice of shooting full frame or half frame images, even changing back and forth in the middle of the same roll. And what might be the Auto-Reflex’s best feature, is that you have a selection of excellent Hexanon lenses to shoot it with. This is an attractive, easy to use, and well built camera, that’s a ton of fun to use, and also delivers the goods when it comes to nice images. Highly recommended!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Konica_Autoreflex#Konica_Auto-Reflex.2C_Autorex_and_Revue_Auto-Reflex

http://www.konicafiles.com/slr-bodies/-auto-reflex-1965/

https://www.cameraquest.com/konihalf.htm

http://www.buhla.de/Foto/Konica/eARHaupt.html

https://www.photo.net/discuss/threads/the-inimitable-konica-auto-reflex.428197/

https://medium.com/@timgallo/my-first-camera-review-d6fd37ee9eb6

Very nice! I’ve been curious about this camera for years. I had an Autoreflex T3 for a while and really liked it, and its 50mm lens was sublime. One can only keep so many SLRs though.

You’re not wrong about having too many SLRs. I didn’t mention it in the review, but one of the things that annoyed me about the Auto-Reflex, is that until I had one, I had successfully been able to stay away from Konica SLRs. At least that was one less lens mount I had to keep track of. The Auto-Reflex is so good however, that it’s worth owning and meant I had to start collecting Konica AR-mount lenses! 🙂

I saw the first Konica Auto-Reflex in early 1969, when a visiting professor on sabbatical asked if he could take a few pictures of me. I was interested in this novel 35mm SLR, which looked like something from another age. (I was a Nikkormat FTN user by then.) He took some profile and full face photos, which I found interesting. (I think he was from a Midwest college/university where Asians were a rare sight.)

I mentally filed this experience under “Jason Schneider/Camera Collector in real life: interesting cameras I’ve seen” file. Later on, I saw an Art student using a Asahi Pentax with a semi-auto lens, taking photos of artwork. (He had to recock the lens to open it to focus/frame after each shot, which intrigued me. (Lenses of the time were either Automatic or Pre-Set manual back then.)

The great thing about today is, all those interesting cameras that you put into the back of your mind, are now affordable to just try yourself. If you could go back 40 years and tell yourself that one day you’d have a collection of Nikons, Canons, Minoltas, Konicas, Rolleis, Leicas, and other cameras all at the same time, you’d think you were crazy!

Nice review, and well written.

But why, oh why do you insist on putting down the equipment on highly abrasive concrete and stone‽

Even if you lift it straight up and down there is still the risk of pressure marks and stones/sand sticking to the metal. Scratching and getting inside the body later.

And why even run the risk‽

It’s better than smashing them later! 🙂

Wow – a fine review of a favorite camera! I have a couple Auto-Reflexes and one or two each of all the following models thru the T4 (the last non-electronic and non-motorized Konica SLR). All were purchased to have the ability to shoot those outstanding Hexanon lenses. Might be just my luck, but the two original Auto-Reflexes have proven to have the most reliable shutters of the bunch. Regarding the standard primes; most Konica fanboys including me agree that the AR 50mm f1.7 is a better lens in most every way than the f1.4. You can find EXC examples of the f1.7 on eBay for under $40; well worth grabbing one if you plan to keep shooting Konicas.

This wouldn’t be the only camera where the f/1.7 is a better, or more cost effective option than the f/1.4 lens, but that’s the one that came with this camera. I didn’t go out of my way to get it. The wide angle 35mm f/2.8 is the gem of the lenses I have though.

Super exciting to see your review, Mike! This is one of my favorite SLRs and I think it compares well to anything from that the era in terms of pure build quality. Very fun to shoot with.

Glad you thought the review did the camera justice. I wanted one before you first got yours, but once you started raving about it, my GAS went into overdrive! So while we don’t see eye to eye on Nikon rangefinders or the Argus C3, we’re both Green-o-matic and Auto-Reflex fans! 🙂

Thanks for the great review. I have had mine for a number of years. With both the half frame and the full frame options available on the camera, I settled on the Konica 40mm 1.8, a great lens in any application, but it seems even more perfect as far as field of view on the Auto-Reflex. With 50mm lenses, I found myself wishing for wider coverage, on half frame, on many occasions. As it seems a basic component of GAS that no camera is perfect, my only complaint with the Auto-Reflex is the long shutter button push, followed up by sound that is comparable to a 1950s punch press…..a really loud camera.

That 40mm Konica lens is one that I’ve always been on the lookout for. I know Johnny Sisson loves that lens on the Auto-Reflex both for it’s performance and size. Prior to this camera, I had nothing in the Konica AR mount, so I hadn’t been on the lookout for one, but now I definitely am.

Well written. thank for the history about Konica. I just got this Konica Autorex on 2nd October and just finish my first roll. Glad i choose this camera over penft, ae-1 and fm2 (still new in analog photography, last month is my progress to decide which mechanical camera that i will buy)

This a heavy camera, well made build, the shutter sound is unique point, but sometime when doin street photography, i wish i can make it more silent.

Dear Sir, very fine review. Well done. Only one point: the picture of the autoreflex T1 is in fact a T2. If you ike, I can send a pic of the T1.

Why the shutter speed dial is on the front of the body? When Copal switched from the original “Square” shutter used by the Konica FM and Nikkorex F, to the newer “Square S” used in the Auto-Reflex, the speed change shaft axis was moved to accomodate the new and completely different mechanism. Konica mounted the dial to the shaft and called it done. The Nikkormat of 1965 geared it to a lever that revolved around the lens mount axis. Neat! The Topcon RE-2 used Konica’s solution and mounted the dial to the face of the camera. Later, the Ricoh Singlex and Cosina Hi-Lite followed suit. With the Autoreflex T, Konica added a pair of bevel gears and moved the dial to the top plate. Pretty much everyone who used the Copal Square S shutter adopted this approach. Chinon, Cosina, Minolta, Yashica and eventually Ricoh. Canon was the strange one, using a cord and pulley arrangement on the 1973 Canon EF.

My school system had two of these Konicas back in the early 70s. I think they were attracted to the half frame feature for making film strips. The media director commented that the cameras went for repair several times due to trouble with the film advance related to the two format feature.

Great article as usual. I’ve managed to NOT get into Konicas…but now.

Anyway, there’s an interesting blog series on another site that are translations of a longtime Nikon engineer…in the one on the Nikkormat FT he explains that cameras using earlier Copal Square shutters almost all have front mounted shutter speed dials since the shutter mechanism was oriented horizontally vs. vertically. Interesting series. You can see them here:

https://en.pronews.com/tag/nikons-roots

What’s the 57mm lens focal length when set to half frame?