2020 has been a complete and utter disaster of a year. For myself and probably everyone I know, this has been the worst year ever. A year that should have never happened, and assuming we all survive it, a year in which for the rest of our lives, we will do our best to forget ever happened.

So for this, the 9th edition of my Cameras of the Dead series, I thought I would take a look at three of the worst cameras ever made. Cameras no one ever asked for, cameras so poorly thought out that you couldn’t make them worse even if you tried, cameras so bad that in two of the three examples, were the last their respective companies ever made, cameras so absolutely terrible, that we’re all better off forgetting that they ever existed.

Assuming you haven’t already scrolled down to see which three cameras I’m talking about, you’re probably thinking, “Gee Mike, how could any camera be that bad? I mean, even a pinhole camera has merit, so how bad could it be?” To you, my naïve reader, prepare yourself to have nightmares of the worst kind as you read through my take on three of the worst cameras ever made.

Traid Fotron (1962)

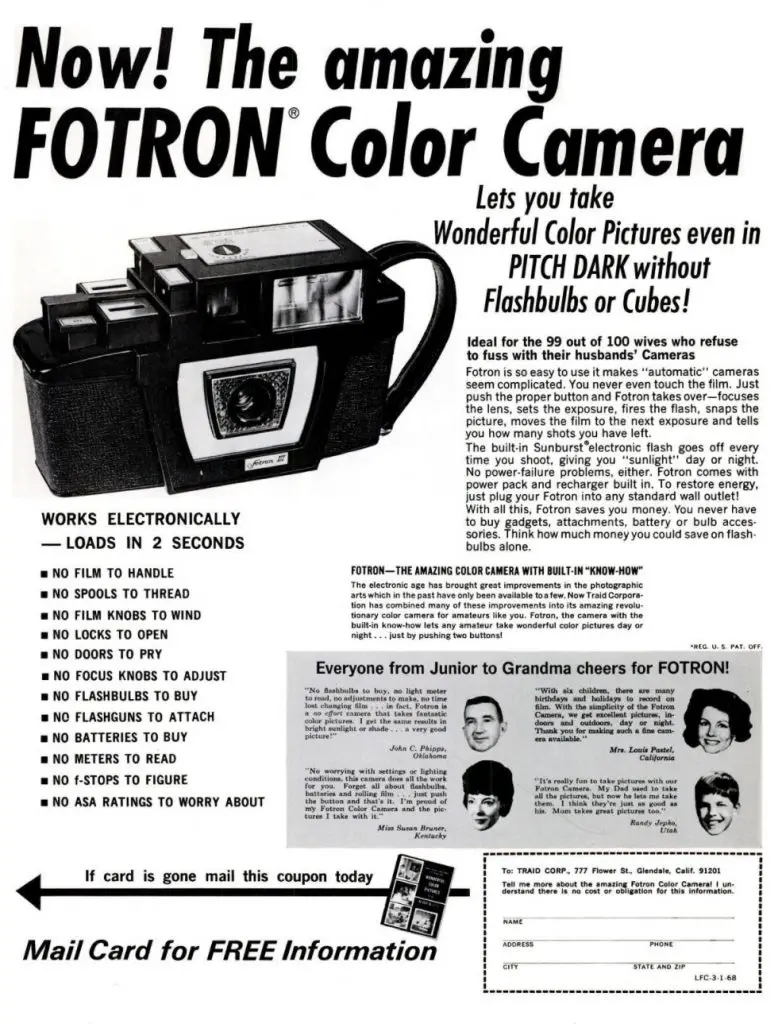

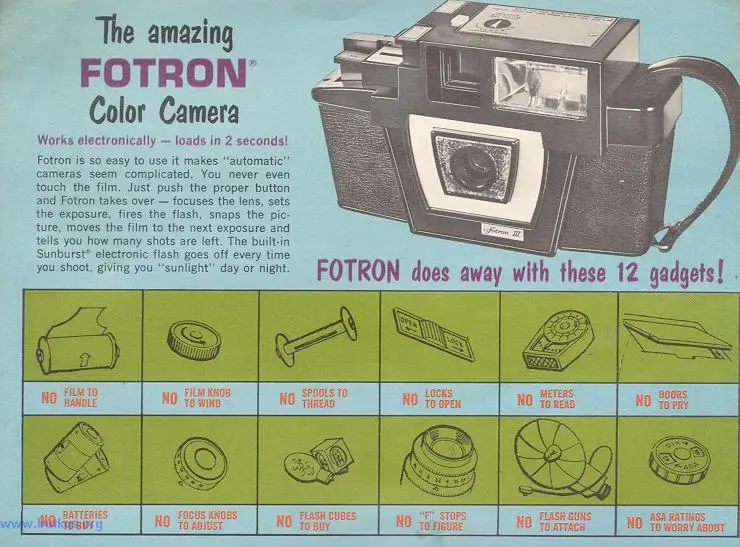

This is a Traid Fotron, a unique point and shoot camera sold by the Traid Corporation of Glendale, California between 1962 and 1971, usually by door to door salesmen. The Fotron shot ten 1 inch by 1 inch exposures on unique Traid film cassettes that were filled with regular Kodak 828 film. The camera featured a built in electronic flash and a unique push button zone focus system that made it extremely simple to use. The camera was powered by a large capacitor inside of the camera that was recharged with regular 120 volt AC via a charging cord that plugs into the bottom. Although simple to use, the camera was sold at an incredibly high price and had shoddy build quality which resulted in a class action lawsuit that put the company out of business.

Film Type: Kodak 828 film loaded into proprietary Fotron “Snap-Load” Cassettes, (ten 1 inch x 1 inch exposures per roll)

Lens: 57mm f/4.5 Fotron anastigmat coated 3-elements

Focus: Three Zone Focus System (4-5 feet, 6-8 feet, 9-12 feet)

Viewfinder: Optical Scale Focus

Shutter: Rotary Metal Blade

Speeds: Single Speed, 1/60 second

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: No Battery, but the camera is powered by a large capacitor

Flash Mount: Built in Electronic Flash

Weight: 1148 grams

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/pdf_files/fotron_traid_corp.pdf

The Worst Ever?

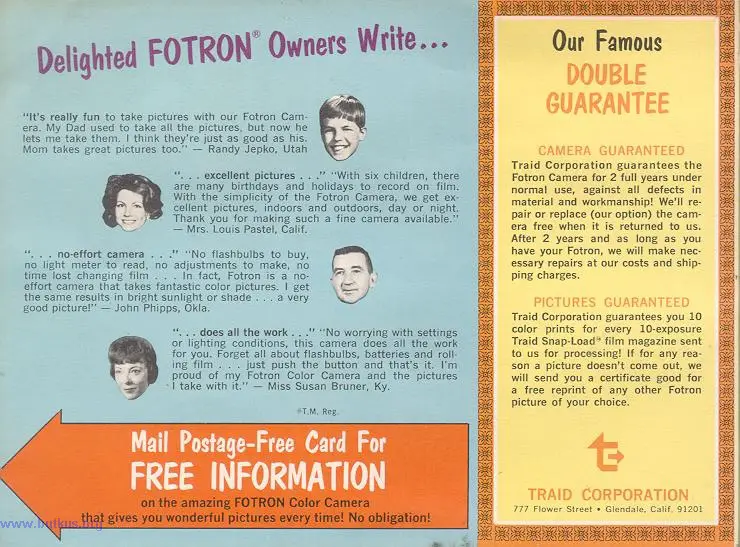

The Fotron is the first camera on this list and most likely the first camera that most collectors think of when asked “What is the worst camera ever made”. The Fotron was a series of three models, all produced by the Traid Corporation of Glendale, California that was sold primarily by door to door salesmen and through back of magazine ads, using questionable sales tactics at prices way beyond what the camera was worth.

The first model in the series came in a gray body and was the only one directly marketed through retail sources. A repeated phrase used in most of Traid’s advertising is that the Fotron was the camera for people who loved Color Pictures, but hated Photography. Although it was never directly admitted to by the company, the Fotron’s target customer was women. In the advertisements above and in the camera’s instruction manual, women were most commonly seen using the camera.

In the ad to the right from the September 9, 1962 issue of the Bryan, Texas Eagle, the camera is plainly referred to as the “Camera Built for Ladies”. The list of features sound pretty good, as it did simplify many parts of photography that might have seemed intimidating to novices of any gender. What’s more interesting is that the price of the camera at the bottom was claimed to be a reasonable $140 with each 10 exposure cassette running $5 including processing, a price much lower than later models were sold for.

There were three different variants of the Fotron, the original with three focusing buttons and a gray body, a second with a black body and still three focusing buttons, and then a Fotron III that still had a black body, but only had two focusing buttons. Other than appearance and the number of focus buttons, everything else about all three Fotron cameras is the same.

Had the story ended with a strange looking camera that aimed to simplify photography with an easy to load snap-in film cartridge, easy push button focus and flash control, automatic film transport, and an in body electronic flash for what would be an inflation adjusted price of $1200, the Fotron likely would not be on this list of the worst cameras ever made,

At some point after the original model’s debut, the decision to stop retail sales and exclusively market the camera through mail order and door to door sales channels is where things went very wrong.

Although the history of who ran the Traid Corporation or who was responsible for the camera’s decisions is unclear, one of the men involved was former Traid president Kenneth M. Harden. Prior to working for Traid, Harden was a former senior vice president of the Encyclopædia Britannica company.

While there, Harden honed his skills as a high pressure salesman, learning tactics that allowed his sales staff to target unknowledgeable customers and trick them into paying way more for a product than common sense would otherwise suggest. Using these tactics, the sales staff at Traid reportedly sold thousands of Traid cameras to customers at ridiculously inflated prices.

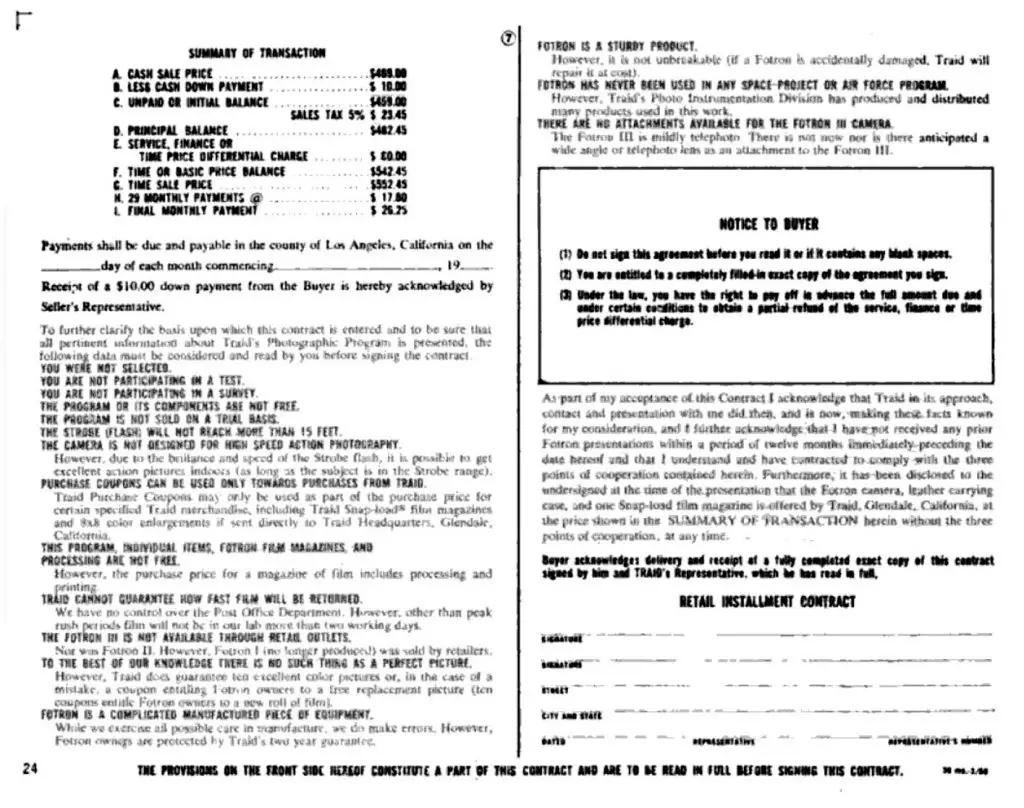

In a scan of the two page contract given to customers upon purchasing a Fotron camera, a large number of disclaimers are listed, the most interesting of which is that the camera is not free. I have never bought anything in my life where I needed to sign a contract that required me to understand that what I am purchasing is not free. Apparently this language was included in the contract as some Traid salespeople reportedly uses tricks to make potential customers believe that the camera was, in fact free.

Even more disturbing is the break down of the price which appears to give customers the option of paying a cash price of $488, or enter into a payment plan requiring only a $10 down payment and then 29 monthly payments of $17.80 with a final month payment of $26.25.

Assuming a customer agreed to this and made all 30 monthly payments, after tax and interest, their total cost for buying the Fotron was an astounding $552.45 which when adjusted for inflation compares to $4600 today! For comparison, at that time, for less than the price of the Fotron, you could have spent your money at Webbs Photo in Palo Alto, CA on a Retina Reflex IV SLR with Schneider-Xenon f/1.9 lens for $278, a Rolleiflex 3.5F for $299.50, or a Leica M3 with the dual range Summicon f/2 lens for $486!

How to Use It

The Fotron was a large and heavy camera with sharp angles, huge swaths of plastic, and a large pleather hand strap on one side. It’s weight of 1148 grams (2.53lbs) actually is better than it could be as the camera’s entire body is plastic. I don’t even care to imagine how heavy this thing would have been had it been inside of a metal body.

The Fotron used proprietary Snap-Load magazines that had Kodak’s 828 roll film inside. The only film available was Kodacolor, meaning that the camera’s primitive exposure system could be tuned to this one film.

The Fotron produced ten 1 inch by 1 inch square images per cassette, and if you so chose, when sending your film to be developed, Traid could make 8 inch by 8 inch enlargements for an additional fee. The images the camera made were incredibly small compared to the comically large size of the camera.

Loading the Snap-Load magazines was incredibly easy. You didn’t even have to open a door like with an Instamatic camera, and upon inserting a new magazine, the camera would automatically advance it to the first exposure, and after the last exposure, would advance it past the paper trailer on the 828 film, so that you could safely remove it from the camera.

The Fotron has it’s own built in electronic flash which was powered not by a battery, but a huge beer can sized capacitor that was charged via an AC charging cord plugged into the camera’s base. Charging the camera took a minimum of 18 hours just to shoot one ten exposure cartridge. If you wanted to try and shoot more than one cartridge, the user manual advises charging the camera for 72 hours!

The top of the camera has an off switch, two power buttons, and three zone focus buttons that also double as the shutter release (there’s only two zone focus buttons on the Fotron III). With the camera off, a black curtain blocks light coming through the viewfinder, making it obvious the camera is off. Both the Indoors and Outdoors On switches turn the camera on and begin charging the flash and also change the focusing range between the focusing buttons. The Fotron’s manual strongly urges you to turn the camera off after every exposure to prolong it’s charge.

Before making an exposure, the manual advises you to wait at least 15 seconds for the camera to reach full power before attempting to fire the shutter. You will know when the camera is ready as two orange lamps on either side of the lens will flash five times. When it is time to make your exposure, the shutter is fired by pressing whichever of the three (two on the Fotron III) focusing buttons are appropriate for your subject. Once an exposure is made, the film is automatically advanced to the next exposure, up to ten, until you reach the end of the roll of film.

Perhaps the most unfortunate thing about the Fotron is that when you look past it’s goofy design and unscrupulous methods for how it was sold, there are a couple nice things I can say about it. For one, having a rechargeable in body electronic flash was actually a pretty cool feature for 1962 when this camera was first sold. Yes, other cameras had electronic flashes, but most beginner cameras still used flashbulbs. The flash was claimed to be rated at 30-watts and in theory could freeze motion like as if you had a faster shutter than you really did.

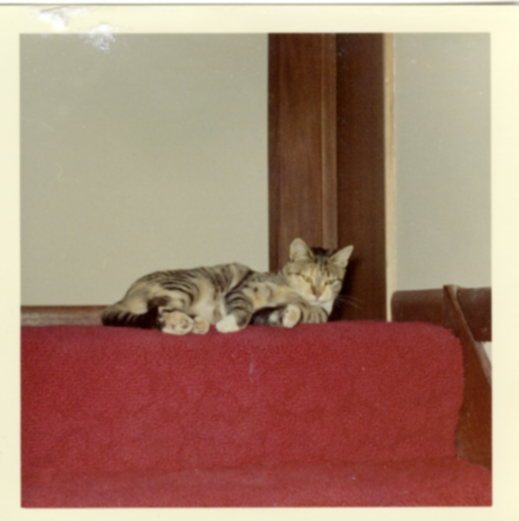

The gallery below of three images comes from Marcy Merrill’s Junk Store Cameras review of the Fotron in which Marcy picked up a camera with an included photo album with some photos shot with the camera. Images used with Marcy’s permission.

The Fotron’s 1 inch square exposures aren’t all that unreasonable, even if they’re dwarfed by the overall size of the camera. Each exposure covered an area of about 605 mm which compared to a standard 24mm x 36mm exposure from a regular 35mm camera was only 30% smaller. And with a decent triplet lens, enlargements of 8×8 were possible.

The idea of creating a camera that never needed batteries with a three-zone (later, two-zone) push button focus, with the simplest film loading sequence of any camera on the market, and a built in electronic flash was actually a good one. You could forgive the huge size as electronics in 1962 were large in any gadget.

No one knows for sure how many Fotrons were sold, but it was said to be in the thousands. As I type this, a quick eBay search for “fotron camera” produces 43 cameras for sale, which suggests that a decent number of them are out there.

Where things went really wrong would later be revealed in a class-action lawsuit from the early 70s called Metowski v. Traid Corp in which 50 named plaintiff’s sued Traid on behalf of 100,000 owners, a number which is likely heavily inflated, accusing the company of misleading it’s customers.

The lawsuit claims the camera was “highly overpriced, clumsy, with poor optical quality, and had few features to recommend”. In a statement regarding the camera being overpriced, it claims that the true value of the Fotron, when taking into account it’s features compared to similar cameras available at the same time to be only $40. How exactly this number was obtained is not clear. In the suit, the class asked for a full refund of the price of the camera, minus the fair value of $40, plus $5000 in damages. A second suit filed against Traid also asked for a refund, but only for $1000 in damages.

The article to the right from the April 25, 1971 issue of the Los Angeles Times describes high pressure sales tactics in which salesman remained in a potential customer’s house for as long as two hours, preying on a lack of knowledge by their sales prospects. One former Traid salesman confirms that at one point during his training, he was told to sell the camera with the idea that the camera would be free, a claim that Traid would deny.

With commissions as high as $175 per camera, the sales people had a huge incentive to push cameras on people. Back then, a $175 commission is comparable to over $1400 today after adjusting for inflation. If they only sold one camera per week, the commission was enough for that salesperson to live in comfort.

It is not clear what outcome this lawsuit had as my attempts to read the legal notes made my head spin. Claims by Traid saying the class-action suit was not valid suggest that it was decided in the plaintiff’s favor, but I honestly never made it to the end.

Whatever the case, the Traid Corporation ceased to exist at any time after this lawsuit and the company never made another photographic product again.

The gallery below shows a 4 page pamphlet produced for the Traid Fotron showing it’s “many virtues”. Whether this pamphlet was used as a marketing tool for sale in camera shops, or part of the literature given to potential customers in door-to-door sales is not known.

Harrison Fotochrome (1965)

This is the Harrison Fotochrome, a solid bodied medium format camera, manufactured in 1965 by Petri of Japan for the Harrison Fotochrome company of Orlando, Florida. The Fotochrome is a strange looking camera that used a proprietary direct positive color film reportedly made by ANSCO that produced ten 2×3 images per roll. After shooting a roll, the film could not be developed by regular labs and needed to be sent back to Harrison for development. Once you had your pictures, there were no negatives, so no copies or enlargements could later be made without first ordering them from Harrison. The camera itself had an all glass Petri lens and a selenium exposure meter. The camera was point and shoot, with no manual exposure settings of any kind. The only shooting option you had, was whether to use the flash or not.

Film Type: Fotochrome Film Packs, (ten 2 inch x 3 inch exposures per roll)

Lens: Unknown focal length f/4.5, coated unknown elements

Focus: 5 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Optical Scale Focus

Shutter: Yes

Speeds: Single Speed, Unknown Speed

Exposure Meter: Coupled Selenium Cell

Battery: 2x AA Alkaline for Flash Only

Flash Mount: Built in Flash Reflector for M3 Flashbulbs

Weight: 740 grams

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/pdf_files/fotochrome_color.pdf

The Worst Ever?

It’s easy to look at a camera like the Traid Fotron and point out all of it’s failures, but at the very least, it did have a specific target customer and although they were poorly executed, some of the camera’s features like the in body electronic flash and the ability to recharge it were pretty cool.

One camera that I can’t think of a single good thing to say about, is the Harrison Fotochrome, an ill-conceived and goofy looking medium format camera produced by a Florida based photofinishing company using proprietary film that can only be developed by sending it back to Harrison, the Fotochrome was such a spectacular failure at every step of the way, that unused cameras, still in their original packaging can easily be found today.

Not much exists online about the Harrison Fotochrome company, but as best as I could tell, they ran a network of photo finishing dealers from the early 1960s to the early 1970s, mostly in pharmacies and department stores, but possibly had some retail stores as well. The ad to the right announcing a “Most Beautiful Child” contest has a list of over a hundred Harrison Fotochrome dealers in the Florida area. Public records on a Florida Commerce website suggest that the company was founded on April 1st (no joke), 1961.

At some point in the early 1960s, someone at the company thought it wasn’t enough to simply develop film made by Kodak and other companies, they thought that perhaps they could expand their reach by coming up with their own camera that used a unique type of film that only they could develop.

Harrison would come up with the design of their eponymous camera, but it would be built in Japan by Petri. The camera would use a proprietary direct positive film made by ANSCO with an ASA rating of 10. The film had an opaque plastic backing, so it could only be exposed through the front, similar to Polaroid’s SX-70 instant film, via a large mirror that reflected the lens image onto it as the shutter opened.

Each roll of film was good for ten 2 inch by 3 inch exposures. It was loaded through the bottom of the camera in a spool to spool fashion and then transported through the camera manually after each exposure was made.

The lens was said to be a Petri f/4.5 lens of unknown focal length and construction. Considering this camera was meant to be inexpensive, and 2×3 prints would are marginally smaller than 6cm x 9cm prints, my best guess is it’s a ~85mm triplet.

Exposure control was completely automatic, via a coupled selenium meter around the lens that controlled the aperture based on available light. I never found any info about the camera’s shutter, but my guess is it’s a single speed design, probably fixed at something like 1/25 or 1/30 of a second to make the most out of the slow ASA 10 film speed.

The ad to the right suggests a price for the camera of under $50, and a per exposure cost including developing of between 15 to 20 cents. Assuming a $2 roll of film (20 cents times 10 exposures) and a $50 camera, when adjusted for inflation, those prices compare to $410 and $16.50 today.

The Fotochrome was designed to be easy to use, so there’s very little in the way of controls for it. Looking down upon the top of the camera, a curved metal reflector for the flash dominates the center. Pressing a small white button to the right pops it open. Forward of the flash release button is the larger, white rectangular shutter release button.

The Fotochrome has double image prevention, so you cannot press the shutter release until after advancing the film, which is done by the large metal wheel on the back of the camera.

The exposure counter is subtractive, showing how many of the ten exposures remain on a roll of film. To the left of the exposure counter is a thin knurled wheel which is how you reset the exposure counter back to ten after loading in a new roll of film. On the far left side of the back is the opening for the viewfinder. Finally, in the center of the back, immediately behind the flash “hump” is the battery compartment where two AA batteries are installed. Having never used this camera, I believe the batteries are only needed for the flash, and not the shutter itself as I think it’s all mechanical.

The bottom of the camera is a large metal film compartment door with 4 small feet to protect it when setting on a flat surface. Opening the door requires sliding a latch on the side of the camera nearest the film advance knob. The door is hinged on the side opposite of the release latch. The first thing you’re likely to see when looking into the film compartment is the large angled mirror that reflects light from the lens to the film plane. The mirror looks like that from a reflex camera, but instead of directing light into the viewfinder, it directs it towards the front of the unexposed film. At a quick glance the film compartment looks like that from a normal 120 roll film camera. Upon closer look, each chamber is larger to accommodate the plastic cassettes that each spool comes in.

Reading the camera’s user manual, it appears that new Fotochrome film came with both a supply and take up cassette already connected by the film’s backing paper. Installing the film looked to be very easy. Simply separate the two cassettes about 2 inches and then press the both into their respective chambers and close the door. At the end of the roll of film, you wind the film into the take up cassette and then send it in for developing.

The viewfinder is just a straight through window, showing an approximation of the exposed image. There are no frame lines or any types of focus aides to estimate focusing distances. To the right of the viewfinder is a small circle that should normally be clear when there is sufficient light for an exposure, with a red flag that will appear where light is too low. Amazingly, the meter still seems to work on this example as I saw the red flag move in and out depending on how much light was hitting the selenium cell.

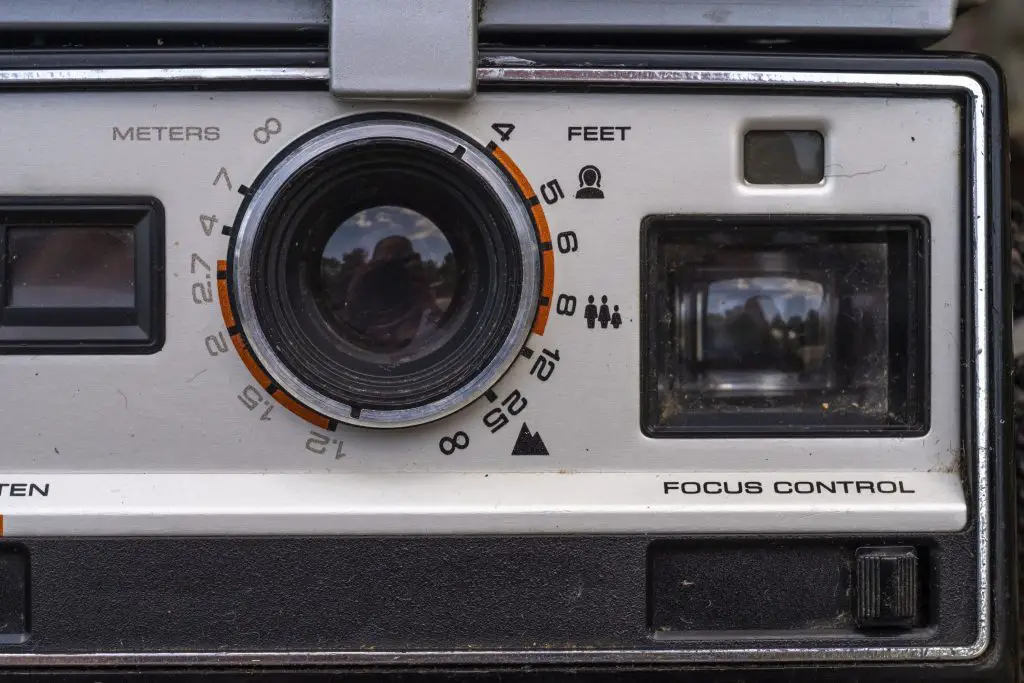

The only other control on the camera is the focus knob around the lens which supports distances from 5 feet to infinity (indicated by an icon of mountains). Although there was no wobble in the focus ring, it feels cheaply made with no dampening, like as if it’s just a metal ring wrapped around the metal lens tube.

The cheapness of the focus ring is prevalent throughout the entire camera. Despite weighing what seems to be a sturdy 740 grams, the entire camera feels lightweight and cheap. The body is mostly some type of die cast plastic, with most metal surfaces being stamped metal. The focus knob has a nice feel to it but otherwise there is nothing luxurious about the camera. With a retail price of under $50, the build quality seems on par for the price, so had the camera used a non-proprietary film, there’s a chance this thing might have been more successful.

Of course, we know now that the Fotochrome wasn’t successful. In a December 2007 post on photo.net, a user named Adolphious St. Clair who claimed to be an employee of Harrison Fotochrome when this camera was sold, says that within 6 weeks of the camera’s introduction, returns of the camera started pouring in as a great deal of them didn’t work properly. Problems with film advance, the flash, and even shutter parts being installed upside down were common problems suggesting an almost non-existent level of quality control.

Word must have quickly spread of the Fotochrome’s reputation as it was only in production for a short time. A huge number of models were never sold and some still remain in their original packaging to this very day. The example I used for this review is one such camera that I picked up on a whim for around $20 in unopened condition.

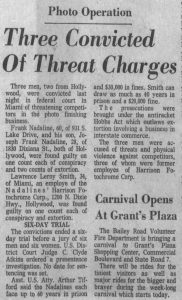

It would seem that Harrison Fotochrome’s business was not affected by the failure of the Fotochrome camera, at least not at first. In my research for this article, I found many advertisements for Harrison’s photo finishing services through the early 1970s, but then in 1971, the company would find itself in the midst of an extortion and racketeering scandal involving company chairman and business operations manager Frank Nadaline and his son, Joseph, who with another employee were charged and later found guilty of trying threatening the life of former Harrison Fotochrome employees who had gone on to work for a competitor.

It would seem that Harrison Fotochrome’s business was not affected by the failure of the Fotochrome camera, at least not at first. In my research for this article, I found many advertisements for Harrison’s photo finishing services through the early 1970s, but then in 1971, the company would find itself in the midst of an extortion and racketeering scandal involving company chairman and business operations manager Frank Nadaline and his son, Joseph, who with another employee were charged and later found guilty of trying threatening the life of former Harrison Fotochrome employees who had gone on to work for a competitor.

During the trial, it was revealed that multiple ex employees were threatened with bricks thrown through windows and in one case, a vehicle was set fire with various other threats made.

In each of these two news clippings, both from Florida newspapers in 1971, the fate of the company was never mentioned, but it can be assumed that after such a scandal, things did not continue to go well for the Harrison Fotochrome company. In a legal notice that appeared in the November 13, 1980 edition of the Miami Herald, it was revealed that the company had filed for bankruptcy protection on February 2, 1976 in the Broward County, Florida circuit court, confirming the company did not survive the 1970s.

Shooting the Fotochrome

Unlike the other two cameras in this article, the Fotochrome is the only that appears to work correctly. The film advance works as it should, the shutter fires, and even the exposure meter detects light. The requirement of proprietary film however, is the deal breaker making this camera impossible to shoot without modding it to use 120 roll film.

When I first acquired this camera back in 2018, I had thought of attempting to shoot the camera using one of the mods online, but here we are more than two years later and that hasn’t happened. There’s two articles online, one on instructables, and another by Stephen Connolly on his blog. Both methods require a little more than the typical extinct film mod due to the way the camera works and even after successfully getting regular 120 film to transport in the camera, you still have to deal with the Fotochrome’s slow shutter which was designed for the original film’s ASA 10 speed rating. The simplest way to do this is to simply tape some type of neutral density filter over the lens to reduce the amount of light entering the camera. It’s a rather convoluted process for a cheaply built that camera that frankly, in two years, I could never build up enough excitement to want to try.

Kodak Colorburst 100 (1978)

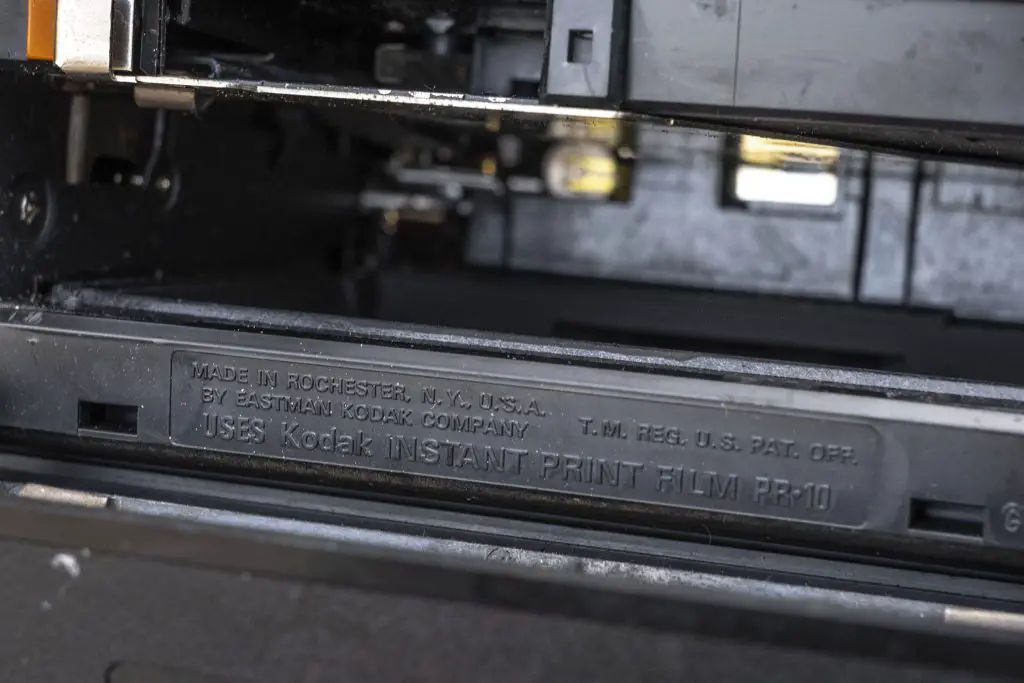

This is a Kodak Colorburst 100, an instant film camera produced by the Eastman Kodak Company between 1978 and 1980. The Colorburst 100 was also sold overseas as the EK100 and was one of the higher end models in Kodak’s new line of instant film cameras, created to compete with Polaroid’s instant film monopoly. Kodak’s instant film system was both simpler and less costly to make and was thought to be a inexpensive alternative to Polaroid’s. The Colorburst 100 had a motorized film transport, full focus capability, exposure control, and a socket up top for an optional flash module. A legal battle would occur in the early 1980s which resulted in 1986 of a federal injunction, prohibiting Kodak from producing their instant film or cameras, abruptly bringing their reign as a Polaroid alternative to an end.

Film Type: Kodak Instant Film Pack (ten exposures per pack)

Lens: 137mm f/11 Coated 4-elements

Focus: 4 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Scale Focus with Projected Frame Lines

Shutter: Yes

Speeds: Single Speed, Unknown Speed

Exposure Meter: Coupled CdS Meter with Programmed AE

Battery: 6v Size J / 4LR61 Battery Pack

Flash: Auxiliary Flash Port

Weight: 818 grams, 989 grams (w/ flash)

Manual: https://mikeeckman.com/media/KodakColorburst100Manual.pdf

The Worst Ever?

If you grew up in the 1980s or 90s and someone mentioned instant photography, the name that everyone thought of was Polaroid. Much like Kleenex, Chap-Stick, Xerox, and Band-Aids, each of these brand names became synonymous with their most successful product, even if the product you’re actually using wasn’t made by that company.

When someone needs to blow their nose or make a photocopy of a document, do they actually care if they’re given a facial tissue made by Scott or are using a copy machine made by Ricoh? Polaroid was one of these companies as they were so successful at instant photography that even when there was competition in the market, people still referred to them as Polaroids.

Being the world’s leader in production of photographic film, it’s probably no surprise that the Eastman Kodak Company tried their hand at instant film photography too. With the release of their Kodak Instant film in 1976, Kodak directly competed with Polaroid’s monopoly in the segment.

What many people may not have known however, is that Kodak didn’t just simply decide to start making instant film prior to that film’s release. In fact, Kodak had worked with Polaroid, making the negative part of Polaroid’s instant film from as far back as 1963. In my research for this article, I found the same information over and over that Kodak had planned on releasing their own brand of Polaroid’s roll film to be used in Polaroid cameras but when Polaroid released the SX-70 with it’s new integrated design, they scrapped those plans and started working on something different.

It is unclear how the marriage between Polaroid and Kodak ended. Was it an amicable break up or a bitter one? My best guess is the latter as when Kodak released Kodak Instant in 1976, Polaroid took exception and quickly filed a lawsuit against their former partner, which would eventually lead to the discontinuation of all Kodak Instant film when the lawsuit concluded in 1986.

Despite what sounds like one big company ripping off the technology of another, Kodak’s Instant film was quite a bit different from Polaroid’s. Each exposed image was rectangular instead of square, which was thought to be more familiar to those used to 35mm cameras. Another major change was that Kodak Instant film did not contain a battery like Polaroid’s did. All power came from a battery within the camera, not the film, which allowed the film to be manufactured cheaper, and although it likely wasn’t a big concern back in the 1970s like it would be today, was also better for the environment.

Also, Kodak’s film is exposed directly from the back, rather than reflected via a mirror through the front like Polaroid’s system was. This allowed for more compact and flatter cameras that didn’t need a large angled mirror inside of the camera to reflect the image. Another benefit of exposing from the back is that Kodak’s images could have a matte texture which was more resistant to finger prints, reduced glare, and also allowed for sharper looking images.

Finally, with the later Trimprint feature, each Kodak Instant print could be peeled away from the negative image and development chemical pod after the image was done developing, allowing for just the print to be saved, allowing for thinner, and more easily framed images.

Feature for feature, Kodak’s Instant film was cheaper to make, allowed for less expensive cameras, and also had the benefit of sharper and more convenient prints, so why did it fail? I’m no lawyer, but it seems that despite their best intentions, Kodak got a little loose in their adherence to patent law, violating as many as twelve of Polaroid’s patents. At the conclusion of the lawsuit, Kodak was forbidden from manufacturing any more Instant film and was forced to pay Polaroid nearly a billion dollars in damages.

Like Kodak often did with other film formats, Kodak’s instant film cameras were built as “loss leaders” aimed at the low end of the market, failing to realize the middle to high ends of the market. Unlike Polaroid who produced SLR and professional instant film cameras with rangefinders and high end lenses and shutters, Kodak cameras like The Handle, Pleaser, and the entire Colorburst series were cheaply made plastic cameras with mostly plastic lenses, no faster than f/11 and with the exception of only one model, were all manual focus.

Originally, I was going to say that no other company made a camera that used Kodak Instant film, but then I discovered a model called the Continental Colorshot 2000 which used it, although it did nothing to change the low end perception of Kodak’s instant film.

In January 8, 1986, newscasts like the one below announcing the end of Kodak Instant film caused customers to panic, realizing that they would no longer be able to use their cameras again, calling local photo stores and Kodak themselves asking what they should do.

At the end of this video, it explains Kodak’s proposed three options given to users of their Kodak Instant cameras, the third of which is a single share of Kodak stock. I looked up old issues of New York Stock Exchange stock prices and on January 4th, 1986, four days before the above newscast ran, the price for a single share of Kodak stock was worth 51 1/8 ($51.13).

The fallout over Kodak Instant film was yet another strike against Eastman Kodak in the minds of photographers growing tired of the company’s continued reliance on proprietary new film formats that the company would later abandon. In the early days, formats like 828, 620, and 616 were released, mostly as Kodak specific formats, but later formats like Instamatic “type 126” film and Kodak’s short lived Disc film format both failed to stick around for very long too, adding to a growing pile of Kodak failures.

How to Use It

At the time of it’s release the Kodak Colorburst 100 was the first in the new Colorburst series featuring a full focusing glass lens, exposure compensation, and support for electronic flashes. The next two models in the series, the 200 and 300 added a protective door over the lens and controls plus a battery test button, and a built in electronic flash, respectively.

The Colorburst had a retail price of $44.95 for the camera and $7.50 for a ten exposure pack of film which when adjusted for inflation, compare to $180 and $30 today.

Using the camera was an ergonomic nightmare featuring a large triangular protrusion on the back of the camera that hits you right in the nose as you press your face up to the viewfinder.

On opposite sides of the front top of the camera are two plastic sliders, one for exposure control and the other for focus. The scale focus viewfinder has what Kodak called the “zooming circle” which the manual suggests is only for taking pictures of people. It’s designed in a way where as you change focus on the camera, the size of the circle changes. When the entirety of someone’s head is within the circle, the image is supposedly in focus. Without the ability to shoot this camera, I couldn’t test this myself, but it seems rather crude, and for the life of me, I can’t see how it would work. There is no attempt to aide in focusing when shooting photos of something other than someone’s head.

Take a look at the two images below I took through the camera’s viewfinder. In the left image, the camera is focused to infinity, and in the right, at minimum focus.

Also within the viewfinder is a projected bright line that frames your image and a small red LED that indicates that there is not enough light to properly expose the image without a flash.

With the optional ITT Magicflash seen here, a two position slide is on top that allows you to change flash ranges from 4-6 feet and 6-10 feet. The only difference between the two is that at the closer position, a tinted window slides in front of the flash to lessen it’s output.

The shutter release is in easy reach of the photographer’s right index finger and the only thing seen on the camera’s left side is strangely located 1/4″ tripod socket. The lack of any slow speeds or even the ability to rotate the camera into landscape orientation with it mounted make the inclusion of this socket strange.

The bottom of the camera is hinged to reveal both the battery and film compartment. You better hope you never have to change the Type J lithium battery while film is loaded into the camera as doing so can fog the remaining exposures. Changing film is much like Polaroid’s SX and One Step cameras in which a film pack is first removed from a light protective foil packet, and then inserted into the camera. An orange stripe would have existed along the top of a new film pack to indicate which side of the pack faces up. After closing the camera, you must press the shutter release once to eject the paper dark slide to get it ready for the first exposure.

In my youth, I knew plenty of people who had Polaroid instant cameras, but no one I ever knew had one of the Kodak Instant ones. I didn’t even know Kodak made instant film until after I started collecting cameras, so I can only assume that a large number of people reading this article probably had a similar experience as well.

After reading of Kodak’s improvements to Polaroid’s instant film, I wish I could try one. The thing is, had the lawsuit between Polaroid and Kodak never happened, I still don’t think Kodak would have been much more successful than Polaroid. After holding the Colorburst 100 and looking at the different options that existed, these were cheaply made cameras. There was no higher end model with better lenses and improved build quality.

Kodak was then and always has been, a film first company, and it’s never been more apparent than with these cameras. Kodak made these things for no other reason than to sell film. They had no interest in making a better camera, just something good enough so that people would buy their film and that’s a damn shame, as we’ve seen throughout many different parts of the 20th century, when Kodak really wanted to make a good camera, they did….they just didn’t do it very often.

Conclusion

As I conclude this, the 9th edition of the Cameras of the Dead series, can I say with absolutely certainty that each of these three cameras are actually the worst ever made? No.

If I’m being perfectly honest, both the Traid Fotron and the Kodak Colorburst actually have some pretty decent features that gave them somewhat of a leg up over competing models. The Traid is one of the first cameras ever made with a rechargeable power source and a built in electronic flash. It’s “Snap-Load” cassettes were pretty easy to load, and with a three range zone focus system, it was superior to simpler fixed focus cameras.

Kodak’s Instant film had some pretty big improvements over Polaroid’s pack film, namely it was cheaper, better for the environment, and produced images with a matte finish less likely to develop fingerprints.

I can’t really come up with anything good to say about the Fotochrome other than that Petri made some pretty terrific lenses back then, so the Petri triplet likely would have been capable of some nice images.

With the countless cheap Chinese made all-plastic disposable and single use cameras that would follow these, there are definitely many cameras that are technically worse. The rash of “scameras and trashcams” like the Canon DL-9000 and Royal Big View that looked like pro level SLRs were abominations of the highest level.

So maybe these aren’t three of the worst cameras ever made, but as I come to this conclusion after typing nearly 7000 words in this article, I am not going to start over!

Haha — had to comment before even reading the whole post (but I will read it all!) — I picked up a Fotron just as a curiosity — and to go in my “Circus Sideshow” of cameras display — and yes, it is much larger than you’d think — and having some knowledge of electronics, I saw this thing as an electrocution just waiting to happen!!! “Here little Johnny — aim this at Mommy, push this button here and ZAP” It ranks up there with the $2000+ door-to-door salesman vacuums which were actually $25 pieces of, uh, nonsense! Thank you for bringing it, and these others, up — I still find it amazing that analog photography works in $2000+ Leica cameras all the way down to pinhole cameras made with a shoebox or a large food can. So having a crazy, “Frankenstein” inspired camera here and there is not unexpected….

Not sure how true this is but I heard part of the technology from Kodak Instant went on it’s way to Fuji’s Instax, originally only released in Japan to prevent a lawsuit from Polaroid.

The Triad, the Fotochrome … now where have I seen this Kodak-killer marketing strategy before? The strategy that designs a camera around a unique size of film, made only by one company, processes only by factory-owned labs? The goal being to topple mighty Eastman from their dominant position in the industry? Hmm … UNIVEX, that’s where, with their “OO” film and cameras that were designed around it.

Fascinating article, Mike. A carry over from the push button focusing can be found in an Ilford Sportsman model, an otherwise conventional 35mm point and shoot manual camera but with four push buttons on the front for predetermined focusing distances.

The film type used in the Fotochrome reminded me of Gratispool whose first film was on paper and likewise could only be processed properly by the company. As its name suggests the 120 film was free and users only paid for processing and prints. By all accounts the IQ wasn’t bad and was very popular in the UK in the 50’s and 60’s due to the postcard size and the company didn’t rip off its customers. As I understand it popularity waned in the 1970’s with the emergence of inexpensive High Street chains catering for conventional 35mm colour film.

My only experience with the film was when I decided to develop it myself, this is when I discovered the problem for DIY photography.

I actually remember seeing a Fotron camera in action, it was sometime in the mid 60’s at some school event. A woman in the audience was using one and with every exposure people were turning to see what all the noise was about, it sounded like a garbage disposal!

Ya know, I don’t know that anyone has ever conclusively determined that the Fotron WASN’T a garbage disposal! 🙂

Mike, thank you for a trip through time back to my grandparents’ house in the countryside south of Houston, probably some time in the late ’70s. My grandfather was not a true photographer, but definitely an avid snapshooter. He owned a series of simple and inexpensive cameras, usually 110 format, but several instant-film models and at least one of the late and unlamented Kodak Discs. Luckily, I have a trunk full of thousands of pictures he took of our family through the years, and I was always curious about the rectangular “Polaroids” that didn’t quite look like the other square format instant images. It just seemed like he must have owned a short-lived Polaroid model at some point.

Then, as I read this article and came across the images of the Kodak Colorburst, some long dormant memories stirred in the silt of my brain. Something seemed vaguely familiar about that strange rectangular box with the circle at the top. I began to recall the physical motion of my fingers sliding the two switches on the front for focus and exposure control. What finally brought the memories fully back to life was the image of the back of the camera. I must have looked through that viewfinder quite a bit as a kid, because I definitely remember the odd triangular hump and how it made the camera quite difficult to comfortably hold. My grandfather didn’t let the grandkids take too many pictures, but he would let us help load and unload the film cassettes, and I distinctly recall sliding a new pack of film into the bottom, closing the lid, and getting to press the shutter and having the paper spit out.

The Colorburst is long gone, along with my grandparents and the house that most of the rectangular instant photos were taken in, but thank you for bringing a little clarity to the unique nature of those Kodak “Polaroids” and for a much needed trip down memory lane!

I always love hearing stories like this. I write these articles not only for the people looking to shoot and collect old cameras, but also people who just want to take a trip down memory lane! Who knows, maybe if you continue to read the site, you’ll find more articles that job some part of your memory! 🙂

I have owned and written about all three of these horrors for Australian publications in a series on great photographic disasters (Nikon RS anyone?) though shooting with them is no longer possible. Interesting that all three were at the core of serious legal actions.

One comment I’d like to add is that the Fotochrome is often claimed to be a Petri product and you suggest that the lens has that origin. However the legal case brought by Harrison over poor quality and the counter suit for non-payment show the other party to be Copal. I suspect that Copal were the lead company in the manufacture, buying in the components. It was a significant action, being one of the first to set set the ground rules for international trade disputes and is well known in US international law – better so than in the phootgraphic community!