This review is part of the Cameras of the Dead series which I have been publishing every year on Halloween and “Halfway to” Halloween, featuring three cameras that I’ve wanted to review that either didn’t work, or was otherwise unable to shoot.

This review is part of the Cameras of the Dead series which I have been publishing every year on Halloween and “Halfway to” Halloween, featuring three cameras that I’ve wanted to review that either didn’t work, or was otherwise unable to shoot.

I am republishing each of those individual reviews this October in anticipation of this Halloween’s Cameras of the Dead post as a way to revisit the cameras of the past that allows them to be properly indexed on the site.

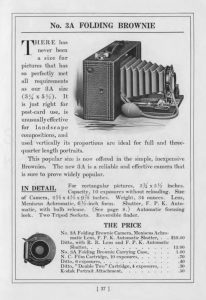

This is a Kodak No. 3A Folding Brownie made by the Eastman Kodak Company from 1909 to 1915. The No. 3A version of this camera took very large “postcard” sized images on 122 format film. There was a slightly smaller variant of this camera known as the No. 3 Folding Brownie that took smaller images on 124 film. The Folding Brownie series were Kodaks least expensive folding roll film cameras designed to make large contact prints using inexpensive film. Despite their cheap prices, they were solidly built of wood with metal fittings, covered with leather which in the case of this example, has held up well over the past century.

Film Type: 122 Roll Film (six 5 ½” x 3 ¼” exposures per roll)

Film Type: 122 Roll Film (six 5 ½” x 3 ¼” exposures per roll)

Lens: Unknown Focal Length Meniscus Achromat Uncoated single-element

Focus: 6 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Scale Focus Reflecting Watson Type Finder

Shutter: FPK Automatic Metal Blade

Speeds: T, B, I

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Weight: 1027 grams

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/kodak_pdf/kodak_brownie_folding_3_3a.pdf

My Thoughts

This No.3A Folding Brownie is likely the oldest camera in my collection, being made between the years of 1909 and 1915. As best as I can tell, at some point in it’s production, Kodak switched from red to black bellows suggesting mine is an earlier variant. It is usually pretty difficult to narrow down the exact years of production of these old Kodaks, so as a general rule I just consider them to be made in the first year I knew that model existed.

This camera came to me via Facebook, and I was alerted to it by my wife (who regularly chides me for my collection). The lady selling it was asking $200 and I politely PMed her and asked how she came to that price and she said she just made one up, without any basis for it’s worth. I ended up talking her down to $20 and met her on my lunch break one day in a McDonald’s parking lot and picked it up.

The Folding Brownie was in excellent condition when I first opened it. Other than a surface layer of dust, the camera was completely in tact, with what looked to be light tight bellows. The leather handle on top of the camera was not only still attached to the camera, but it showed no signs of cracks or tears, something you rarely see on early 20th century box and folding cameras. The shutter was left open in “T” mode, so I released it from it’s (likely) decades long prison and tested the Instant mode, to which the camera responded as it should. I should point out that many of these earlier Kodaks had a lens design in which the glass lens element is behind the shutter. Looking at the front of the camera, someone not familiar with it’s design might think the lens is missing, when in reality the lens is behind the shutter. This is actually a good thing as the shutter acts as a built in lens cap, protecting the glass elements from dust and debris.

I declared this one a winner, mostly. While the camera seemed to be in perfect working order, this is a No.3A which means it uses type 122 roll film which was one of the largest types of roll film ever made. Each exposed image is nearly half a foot wide. Take a look at the image to the left where I show a 122 spool next to a (still very large) 116 spool and 120 spool. Back when cameras like this were made, photography was still an expensive industry. Models like the Folding Brownie might have been affordable by the mid to lower class, but developing the film cost money. Even after developing the film, you still needed a way to make prints from your exposed negatives which typically involves some type of enlarger to make images big enough to be framed.

I declared this one a winner, mostly. While the camera seemed to be in perfect working order, this is a No.3A which means it uses type 122 roll film which was one of the largest types of roll film ever made. Each exposed image is nearly half a foot wide. Take a look at the image to the left where I show a 122 spool next to a (still very large) 116 spool and 120 spool. Back when cameras like this were made, photography was still an expensive industry. Models like the Folding Brownie might have been affordable by the mid to lower class, but developing the film cost money. Even after developing the film, you still needed a way to make prints from your exposed negatives which typically involves some type of enlarger to make images big enough to be framed.

Folding Brownies like this No.3A were popular because they made images that were already about the size of a post card and didn’t need to be enlargened. When film was developed, the end result would be created via something called a contact print. A contact print is basically when you take an exposed negative and put it in contact with light sensitive paper and momentarily shine light through the film to “print” a positive image on the photographic paper. Of course, this still needs to be done in a darkroom with chemicals to stabilize the light sensitive paper, but the benefit is that large complex equipment like an enlarger was not necessary.

When you would shoot images in a camera like this, you would send out your film to be developed (or do it yourself) and then take your exposed film and make positive prints directly from the negatives that were the same exact size. If you were ever in an antique shop and saw an old photo album that had photographs that measured 5 ½” x 3 ¼”, it is very possible they were shot using a 122 film camera like this one.

The Folding Brownie is a pretty neat camera. When folded, it resembles a medium sized box. To someone not familiar with old cameras, they likely would have no idea that this was even a camera. To open the front, a hidden button on the top of the camera right in front of the handle must be pressed to unlock the door. This is not a self-erecting design, which means that once the door is opened, you must manually pull out the lens and shutter by gripping the shiny metal handle immediately below the lens.

Unlike other folding Kodaks in my collection, the Brownie has click-stops at various focusing distances which means the camera will lock in at one of 8 focusing distances from 6 feet to 100 feet (infinity). While this may seem limiting today, the reality is that these cameras never needed precise focus to begin with, so each of the set distances on the focusing plate are more than enough to cover any distance. This is especially convenient today, as many of the earlier folding cameras I’ve encountered struggled to stay at their proper focusing distances. Over time, things loosen up, but that wouldn’t be a problem with this camera as once the camera is set to a specific distance, you must press down on the locking lever to move it to another distance.

All of the camera’s controls are on the shutter itself. At the 12 o’clock position is the shutter speed selector. You only have three choices here, T (for Time), B (for Bulb), and I (for Instant which is approximately 1/25th second). At the 6 o’clock position is the aperture selector, which gives you values from 8 to 128.

If the thought of an aperture of f/128 sounds strange, you should know that prior to the 1920s, Kodak used a different system for calculating f/stops known as the US System or “Uniform Standard” (also sometimes incorrectly called the Universal System), which was originally developed by the Photographic Society of Great Britain in the 1880s. Using this system, the Folding Brownie’s maximum and minimum apertures of 8 and 128 are actually closer to f/11 and f/45 using the modern system we use today.

Finally, the last thing on the shutter is the shutter release which is near the 11 o’clock position. The shutter release on this camera is not threaded for a cable, and there is no self timer. At the 9’clock position is a chrome cylinder which an air piston inside of it that acts as an actuator to fire the shutter.

Considering the excellent condition of this 100+ year old camera, I really wanted to try and shoot some images through it, but a combination of the sheer size of 122 film, and the fact that the camera only came with one spool meant I would have had to either get really creative and insert single sheets of 4×5 film in the camera and figure out a way how to protect it and develop it, or fab up some type of 120 to 122 adapter and shoot some super panoramic 5 ½” x 2 ¼” on 120 film. I decided to just admire the camera for it’s beauty and talk about it here in my Cameras of the Dead series. While the camera itself is still very much alive, it’s film format has long gone the way of the dinosaur and prices for expired 122 film in eBay are in the $40+ and up range. Wikipedia suggests that 122 film went out of production in 1971 so my options would be extremely limited for viable original film.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

https://camerapedia.fandom.com/wiki/Kodak_No._3A_Folding_Brownie_Model_A

http://web.archive.org/web/20160709005404/http://www.geh.org/fm/brownie/htmlsrc/mE13000452_ful.html (archived)

http://licm.org.uk/livingImage/Kodak_No3A-Folding-Brownie.html

Great article as always.

Seeing that 122 film is/was a 5.5″ X 3.25″ roll film format, I would have started looking for bulk aerial camera film carried by Freestyle Sales Co., got out blunt-tip scissors, and “taken off” from there. (It’s a 1960’s thing, when war surplus aerial cameras were advertised in photography magazines.)

As for backing paper, a local paper maker might come through with a limited run of the hand made variety. Could you turn out “postcard pix” just to see if it could be done? These are the days of 3D printers that make it (somewhat) possible to use 135 film in a 126 Instamatic camera. Let the Film Photography Project folk take a look at this early 20th century beast, and who know knows what will emerge from that inspired idea factory!;)

I am told Film for Classics still makes a custom 122 roll film with 6 exposures. They don’t sell their film directly and according to their website, every dealer of theirs is out of stock, so I am unsure if it’s still available, but hopefully one of these days, I’ll get a chance to shoot this camera.

This is one of the first cameras I bought on ebay back in 1996. Mine is missing the handle. But I love the red bellows and the satin brass finish. Thanks for the information, Mike. As always, your articles are great!

Thanks Jim! I actually just updated the review a little while ago, correcting some mistakes another reader pointed out, so it’s even better now than it was!

In addition to the Kodak I also own a very similar camera — Ansco Junior Model A. It was produced between 1906 and 1913 and also takes 122 film. I have a Kodak Autographic 3A Model C which also takes 122 film. These cameras were designed to produce do-it-yourself Post Cards.

I’m surprised no one has suggested using photographic paper as a negative. It would mean long exposures, but not as long as folks use every day for pinholes.

That would certainly work too and be easier to source. My particular issue now is that I don’t have a good means for developing photographer paper, glass plates, or sheet film. I am currently limited to roll films only, but perhaps in the future I may upgrade my developing area.

Great article! What is the squeezing bulb thing for that is hooked up to the shutter in the advertisement? Does the shutter today work without that bulb attachment?

Those bulbs you see in old camera advertisements were remote shutter releases. Normally air fills the rubber bulb and theres a hollow tube connected to the shutter release on the camera. When the photographer wants to take a photo, he would squeeze the bulb and the air would travel through the tube and press the shutter release. This allows him or her to fire the shutter while standing away from the camera. Those bulbs are just optional though, the camera can still be used without one. They sure do look cool though! 🙂

and a couple more impressive examples…

https://www.flickr.com/photos/95346384@N07/32860327395/

https://www.flickr.com/photos/journeysend1750/49125164072/

That’s interesting! Well, today I won the bidding on the exact same model camera as yours, so it will soon be a new project. I found your very timely recent article when I was researching film type 122 model cameras, because I had the idea of using their large film size for film panoramas since I love the panoramic aspect ratio.

So to answer the question in your article of what to do with actually using this camera for film, the plan is to buy some 122-120 spool adapters (they are only $10 to $20 online for the pack of 4 needed), and put in standard 120 film, to get a high quality, yet authentic vintage style film panorama, that can look like this: https://www.flickr.com/photos/journeysend1750/41706721042

orhttps://www.flickr.com/photos/71037647@N06/47174162961

Because of course, dedicated film panorama cameras are very, very expensive, especially ones using 120 film quality, but even 35mm ones.

Mike, in case you want to revisit this camera, there are 3D printed 122-to-120 spool adapters available in ebay and other sources, such as:

https://filmphotographystore.com/products/adapter-122-to-120-film-adapter

Some of the later models, like mine, have Bausch & Lomb Rapid Rectilinear lens in front of the shutter. I recently picked up a 3a with a ratty exterior, but nice bellows, lens, and shutter. In the process of converting it to 120 to try making some 6×14 images. Should be an interesting journey.

Thanks for the great reviews.

Excellent write up! I just found one of these at a thrift store. I’m not seeing any light leaks in the gorgeous red bellows and the brass shutter works perfectly! I just ordered a set of 122-120 film adapters and can’t wait to try it out.

Thanks for the comment! Good luck with the adapter. If you get any good images with them in this camera, please share!

Good description. I have the model with red bellows. R.R lens and it is gorgeous. Sharp and soft at the same time. Have used x-ray film (can be handled in darkroom light), paper negatives and 5×7 film cut to size. Have made a ground glass of thin glass which also support the film during exposure.

I love that camera.

As kid in the mid-1960s beginning to explore photography, my grandfather gave me his 3A and a cigar box full of this negatives, including baby pictures of my Mom, who was born in 1911. I took the negative of one favorite picture, did a high-res scan and had it printed four-feet wide at a local print shop. The resolution held up fine.

The camera itself is in great condition. What a gift!

This is a great story! Many people are often very impressed with the level of detail some early cameras were able to make. Large format cameras from the late 19th and early 20th centuries were very capable devices.