This review is part of the Cameras of the Dead series which I have been publishing every year on Halloween and “Halfway to” Halloween, featuring three cameras that I’ve wanted to review that either didn’t work, or was otherwise unable to shoot.

This review is part of the Cameras of the Dead series which I have been publishing every year on Halloween and “Halfway to” Halloween, featuring three cameras that I’ve wanted to review that either didn’t work, or was otherwise unable to shoot.

I am republishing each of those individual reviews this October in anticipation of this Halloween’s Cameras of the Dead post as a way to revisit the cameras of the past that allows them to be properly indexed on the site.

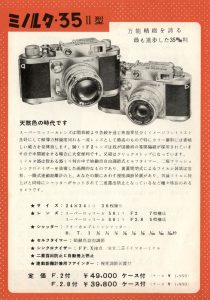

This is a Minolta 35 Model II rangefinder made by Chiyoda Kogaku starting in 1953. Despite the Roman numeral II in the name this was actually the 7th variation of the original Minolta 35, first released in 1947. The entire Minolta 35 series is loosely considered a copy of the Leitz Leica II, but had several significant differences, making it more of a Leica-inspiration, rather than a direct copy. The entire Minolta 35 series was very successful and stayed in production for 12 years before being discontinued in 1959.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 45mm f/2.8 Chiyoko Super Rokkor coated 5-elements

Lens Mount: M39 Screw

Focus: 3 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: T, B, 1 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Coldshoe and FP and X Flash Sync

Weight: 737 grams (w/ lens), 587 grams (body only)

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/minolta_pdf/minolta-35_color.pdf

History

When you think of the most common “Leica Thread Mount” copies of the 20th century, many people probably think of Canon, as they were one of the first to do it, and definitely the first to do it right. Canon’s earliest Leica copies were every bit as good as their German counterparts and also began to improve upon the German design almost from the start.

Besides Canon, you can’t ignore the massive number of Soviet copies, most made by FED and KMZ, who (mostly) successfully recreated the formula. Although the Soviets would eventually improve upon the Leica’s feature set with things like hinged rear doors, combined image coincident rangefinders, and rapid wind levers, the Soviets could never quite match Leitz in build quality like the Japanese did. Beyond that, there were also Leica clones by Nicca/Yashica, Leotax, Tanack, Kardon, and even the Chinese Shanghai copy.

One company that few people would likely associate as making a Leica copy was Minolta, or as they were then called, Chiyoda Kogaku. This is interesting because the man who formed Chiyoda Kogaku, Kazuo Tashima, was infatuated with German camera design so much, that he hired two German technicians to help him build his earliest cameras. The first Minolta cameras were heavily influenced by German models like the Plaubel Makina and the Zeiss-Ikon Ikonta and Icarettes. In 1937, Minolta would launch the Minoltaflex, essentially a copy of Franke & Heidecke’s Rolleicord. The Minoltacord would evolve into the Minolta Autocord, which borrowed (and improved) heavily from the Rolleiflex.

So, with Minolta’s heavy influence of German camera companies, it should be no surprise to know that at one time they did have a Leica-inspired camera which was then called the Minolta 35.

Although Kazuo Tashima clearly had no problem releasing Minolta cameras that were heavily based off German design, he was consistent in that no Minolta camera would ever be an exact copy. Any new camera to bear the Minolta name should improve upon the original model and be unique in it’s own way. It is perhaps this reason that the Minolta 35 is often left off the list of Leica copy cameras as it was quite different from the very beginning.

In fact, the Minolta was more different than it was the same as the Leica, sharing only the same 35mm film format, cloth focal plane shutter (although it was of a different design), 28.8mm “flange to film” distance, and it shared the same 39x1mm screw lens mount.

First released in 1947, the Minolta 35 had a combined coincident image rangefinder, a self-timer, hinged rear film door, and most significantly, shot 24x32mm exposures, which at the time was a standard in Japan, and would yield four extra exposures on a single 36-exposure film cassette. It came standard with a very good Super Rokkor 45mm f/2.8 that was said to be superior to the Leitz Elmar found on many Leicas.

The Minolta 35 was one of the first Japanese made cameras to see success outside of Japan after the war. Although Nippon Kogaku would release their first Nikon rangefinder in 1948 and Canon had been producing their Leica copies since the mid 30s, it was Tashima’s knowledge of the German camera industry and the contacts he had developed which allowed his cameras to get a bit more exposure.

By the early to mid 1950s, the Japanese camera industry exploded, and like their competitors, Chiyoda Kogaku saw success with their interchangeable lens 35mm rangefinders. For reasons that are beyond the scope of this article, Chiyoda decided that continuing to pursue the professional 35mm camera market wasn’t in their interests, and in 1955 would release the Minolta A, a fixed lens, moderately priced rangefinder for the advanced amateur market.

Like Nippon Kogaku, by the end of the 1950s, Chiyoda saw the future of professional photography in the Single Lens Reflex and in 1958 would release the Minolta SR-2 SLR. Less than a year later, the last of the Minolta 35 series would end production.

Today, the Minolta 35 series are highly desirable by collectors as they are the rare example of a “Leica inspired” 35mm rangefinder that never pretended to be a Leica. Sure, later iterations of Canon and Soviet Leica copies evolved quite always from their Leica II roots, but the Minolta 35 was always different from the very beginning. Adding to the allure was Chiyoda Kogaku’s excellent reputation for optics. Like the Canon Serenar and Nippon Kogaku Nikkors, the Rokkor and Super Rokkor lenses are very sharp and can fetch huge dollars both for use on Minolta rangefinders and adapted digital cameras.

My Thoughts

This Minolta 35 Model II was graciously loaned to me by fellow collector Jason Denlinger who had posted on the Facebook Vintage Camera Collectors group asking if anyone knew how to repair them. I am always one for a challenge and offered to take a look at his camera. When it arrived, I could clearly see the cloth shutter curtains had become detached from the spools they were supposed to be connected to. Sadly, this is a common problem with nearly any type of camera with a cloth shutter. Depending on age and how it was stored, the cloth ribbons that hold the curtains together can often become brittle and break, rendering the shutter inoperable. The only “fix” is to replace them.

I contacted Philippines based camera repairman, Jay Javier and asked for his thoughts on how to do this. Jay was gracious enough to send me several articles he had about removing the shutter from the Minolta 35 and replacing the curtains. I quickly realized after reading his notes that I was in over my head. To his credit, Jay tried to convince me that this wasn’t that difficult of a repair and that the Minolta 35 is one of the easier cameras to do this type of job on, but knowing it wasn’t even my camera to begin with, I decided to scrap any plan to repair it.

Without any hope of using this camera as I had hoped, I thought of a way that perhaps I could use the open shutter for some extremely long shutter exposures of the night sky. I found a lens cap that fit the Super Rokkor lens and used it as a way to open and close the shutter and I took it outside and shot some long exposure images of the sky around my house. I’ll just jump to the point where I tell you this didn’t work very well. Frankly, there’s no reason it couldn’t, I just didn’t devote the necessary time to do it right and I rushed the shots. Upon developing the film, I got mostly blank exposures with occasional streaks of light in them.

Had the camera worked however, I can say the Minolta 35 is a fantastic camera. The build quality is excellent, easily as good as anything coming out of Japan or Germany at the time. With a weight of 737 grams with the lens, the Minolta 35 is about as heavy as a compact SLR from the 1970s but it’s smaller size than an SLR gives an increased illusion of heft.

The viewfinder was of the coincident image variety that Canon and Nippon Kogaku were using at the same time. While not as small as pre-war rangefinders, the viewfinder was difficult to see through with prescription glasses. Thankfully, the rear eyepiece has a metal ring around it that when rotated functions as an adjustable diopter which helps matters a bit.

The rangefinder patch on this one was a bit cloudy and had this camera been in working order, I would have opened it up to clean it, but as it was I didn’t bother. Comparing the camera to that of the Nikon M and Canon IIB, I can say that it’s very comparable.

The top plate is where the Minolta resembles the Leica the most, but with a few minor changes around the shutter speed dial and the rewind mode selector. This particular camera was engraved “SHETTEL C.K.S.” The letters “C.K.S.” are original and stand for Chiyoda Kogaku Seiko where the camera was made, but I can only assume “SHETTEL” is the name of a person or company who originally owned this camera. If anyone reading this knows different, please let me know.

Perhaps the biggest improvement that Chiyoda, and nearly every other Japanese company, improved upon from the original Leica was a switch to a hinged rear door, instead of loading film through the bottom. It is said that Leitz’s insistence on bottom loading cameras was to protect the film from light leaks, but it’s just so darn inconvenient!

Being a Leica Thread Mount 35mm camera, means the lens screws off like any other camera with the same mount. There is a coupling arm at the 12 o’clock position of the lens mount that allows the rangefinder to detect the focus distance set on the lens, but otherwise the lens screws in as you would expect. The diameter and pitch of the threads are 39x1mm which means that any German or Japanese LTM lens will work on the Minolta.

The Minolta 35 Model II has a self timer on the front plate with the numbers 1-3 printed in red. The manual strangely doesn’t explain what these numbers mean, but says that a full press of the lever is good for an 8-9 second delay, and “a degree of 1-3 the corresponding time will be about 4 seconds”. I guess what they’re trying to say is that the self timer will work in partial movements of less than 8-9 seconds if you only push it part way.

I really enjoyed this little camera, and am disappointed I couldn’t get it working. After coming back to the original owner and telling him I didn’t want to risk tearing down his camera to repair the shutter curtains, he told me that he really only cared about the lens. He felt he could get far more money for the lens than the camera body itself, so he told me that I could keep the body and I’d only have to send him back the lens, to which I agreed. So as I write this, I still have this camera in my collection, sans lens. Perhaps one day I’ll get enough courage to take Jay Javier’s advice and attempt to repair it. Of course, then I’ll have to call up Jason Denlinger and hope I can buy his lens back!

Although I couldn’t shoot the camera, I was able to handle it and experience what it might have been like. Minolta’s reputation for excellent optics makes me feel confident that had I shot some images, they would have looked marvelous. These Minolta 35s aren’t the cheapest cameras out there, but they’re still a value compared to most Leicas, and with the extra conveniences like the hinged rear door and coincident image rangefinder, they’re a compelling option over a genuine Leica from the same period.

Fun Trivia: The circle with the C symbol on the face of the lens is not a copyright symbol, it is what Chiyoda used to indicate that the lens was color coated.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minolta_35

https://www.canonrangefinder.org/Minolta_Rangefinders.htm

http://corsopolaris.net/supercameras/MinoltaRF/minolta35.html

Hi Mike, what an interesting history. One minor error: the original Leica ltm thread mount is 39mm x 26 tpi. This was a Whitworth standard in that era. Was the Minolta 39×26 tpi or 39×1 (all metric)?

Mike,I have one of these cameras that has been stored away in its leather case for many years and believe it still works. I have no use for it and would consider selling or allowing you to take the photos you were hoping to get. Let me know, thank you for all of your detailed information on this camera.