This is the Rectaflex, a 35mm SLR built in Rome, Italy between the years of 1948 to 1958. It was designed by a Roman lawyer named Telemaco Corsi and was the very first 35mm SLR to feature a pentaprism viewfinder, narrowly beating out the Zeiss-Ikon Contax S as the first camera to have that feature. Other innovative features of the camera are a focal plane shutter with a top 1/1300 shutter speed, an early version of a rapid return reflex mirror, a bayonet lens mount, and a fully flash synchronized shutter. The Rectaflex is a very attractive and also very rare camera to find today, especially in the United States. These cameras are highly sought after by collectors, and when found, often sell for very high prices.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 50mm f/2 Schneider-Kreuznach Xenon coated 6-elements in 5-groups

Lens Mount: Rectaflex Bayonet

Focus: 2 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Fixed SLR Pentaprism

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/1300 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Weight: 972 grams (w/ lens), 704 (body only)

Manual: https://mikeeckman.com/media/RectaflexManual.pdf (This manual was sent to me by Mike Butkus and is not hosted on his site.)

How these ratings work |

The Rectaflex is a historically significant and well built camera, made in Italy with features that would later become standard on SLRs that would follow. The ergonomics and cosmetics of this camera are excellent, making them very desirable to collectors. As a user though, the very dim viewfinder and early implementation of a rapid return mirror make shooting a chore. Combined with some conditional issues with this particular camera, I did not enjoy shooting it. That shouldn’t change any serious collector’s mind about adding one to their collection to proudly display on their shelf, but in terms of using it, there are much better options. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 30% | |

| Bonus | +1 for first pentaprism viewfinder and early rapid return mirror | ||||||

| Final Score | 12.7 | ||||||

History

The origins of the Rectaflex started with a company named SARA (Equipment and Automation Equipment Studies) which during World War II was involved in the manufacture of optical instruments for use by the Italian military. As director of SARA, Telemarco Corsi developed an interest in photography and hoped to one day create his own camera.

Shortly after the war, Corsi met a photographer only known as “Assenza” who showed him a modified Kinoflex SLR camera. The Kinoflex was a leaf shutter 35mm camera that had a waist level viewfinder, as did every other SLR of the day. This particular camera however, had a custom viewfinder that used externally mounted mirrors that reversed the image normally seen in a waist level finder, correcting it for eye level use.

Corsi was intrigued by this new idea and along with a group of like-minded associates began work on a new camera that would incorporate Assenza’s idea, but instead of using mirrors, would use a glass prism.

The new camera would incorporate some designs of German cameras of the era, including a focal plane shutter with speeds as fast as 1/1000, a completely removable film back, and a film cutter for allowing mid roll changes with no support for rewinding the film. For the body, Corsi hired an Italian designer named Giò Ponti. The design of the pentaprism proved to be the most difficult as early prototypes had a flat top prism that only corrected the image from side to side, but not top to bottom.

In June 1947, a prototype known then as the Rectaflex 947 made it’s debut at the Milan Fair. Despite being an early prototype and still using the flat top prism, the camera’s reception was very positive, not only for it’s innovative features, but also it’s elegant styling. With this feedback, Corsi was able to convince the owners of SARA and another firm called Snia Viscosa to fund further development of his new camera.

Now fully funded, Corsi and his team took the feedback they received from the photographic press and continued to improve the camera, eventually creating a new prism that was corrected both side to side and top to bottom.

Exactly a year later at the 1948 Milan fair, a complete and fully functional Rectaflex was revealed. Compared to the prototype from a year earlier, the camera now had an interchangeable bayonet lens mount, removed the slow speed shutter dial from the front of the camera and incorporated a two level shutter speed dial on top, and the film cutting knife was removed allowing the film to be rewound, which was in line with other 35mm cameras of the day.

The first Rectaflex models were given serial numbers in the 1000 range and are known today as the Rectaflex Standard 1000. Unfortunately, these early cameras proved to be very unreliable, with the most common faults in the shutter’s tolerances for the slow speeds. Changes were immediately incorporated into the shutter’s design and with a number of other small improvements, a series 2000 camera would debut in 1949, improving reliability. A simpler model called the Rectaflex Junior was also put into production with a simpler shutter featuring a top 1/500 speed and no slow speeds.

Over the course of the next few years, the Rectaflex would be continually improved with incremental changes to improve reliability and in some cases, add new features such as a new 1/1300 top shutter speed. While improvements are always welcome with any new product, these constant changes caused production delays, and problems with distribution of the camera.

By 1952, most of the Rectaflex’s reliability problems had been resolved and the list of features set, but sales were slow. With less than 5000 total cameras produced since it’s introduction in 1948, the two companies funding the camera were unhappy with the camera’s performance. As a result, Corsi was reassigned to a different role in the company, and a Polish businessmen named Leon Baume was brought in to take over promotion and sales.

At first, it seems that Baume’s contributions helped, as production increased to around 300 cameras a month, with a total of 4500 cameras in the next two years. Baume also was successful at securing an agreement with the US Armed Forces to buy a total of 30,000 cameras over the next five years.

Sadly, after the first year of the contract, production delays caused the US Armed Forces to back out of the deal after only 1500 cameras were delivered. This loss of future revenue, combined with slow sales, and the Rectaflex’s inability to compete with other German cameras and the rapid evolution of the Japanese camera industry resulted in a loss of funding from Snia Viscosa causing the Rectaflex’s factory to be shut down.

After the loss of his company, Telemaco Corsi was not willing to give up and continued to evolve the Rectaflex by himself, further improving the design and adding new features. In 1956, a new Rectaflex prototype with a redesigned pentaprism and film advance lever was shown to Prince Francis Joseph II of Liechtenstein. The Prince, having owned a controlling share of a local optics company called Contina, agreed to purchase the remaining assets of the Rectaflex and put the camera into production in Vaduz, Liechtenstein.

The complexity of the Rectaflex resulted in delays in manufacturing completed cameras. It would take nearly two years before the first new Liechtenstein Rectaflex cameras would be finished. Although still simply called the Rectaflex, the new cameras would feature the Liechtenstein coat of arms below the logo, but other than a few minor cosmetic changes, would otherwise look the same. A total of 300 cameras would be produced in Vaduz, before the project was abandoned once again.

In addition to the main Rectaflex SLR, Telemaco Corsi created a variety of other prototypes and proof of concept cameras including a metered Rectaflex, a Rectaflex Rotor with a turret lens mount, a 35mm rangefinder using the M39 screw mount called the Recta, a similar interchangeable lens rangefinder, but in a completely different body called the Director 35, a 6×6 medium format Rectaflex, and something called the Rectaflex Scientifica which as the name implies, likely would have been used in a laboratory.

Despite being in production for only a couple of years, a large number of lenses by Carl Zeiss, Schneider-Kreuznach, Meyer Görlitz, Steinheil, P.Angenieux, SOM Berthiot, Heinz Kilfitt, and Filotecnica Salmoiraghi Milano produced lenses in the Rectaflex mount.

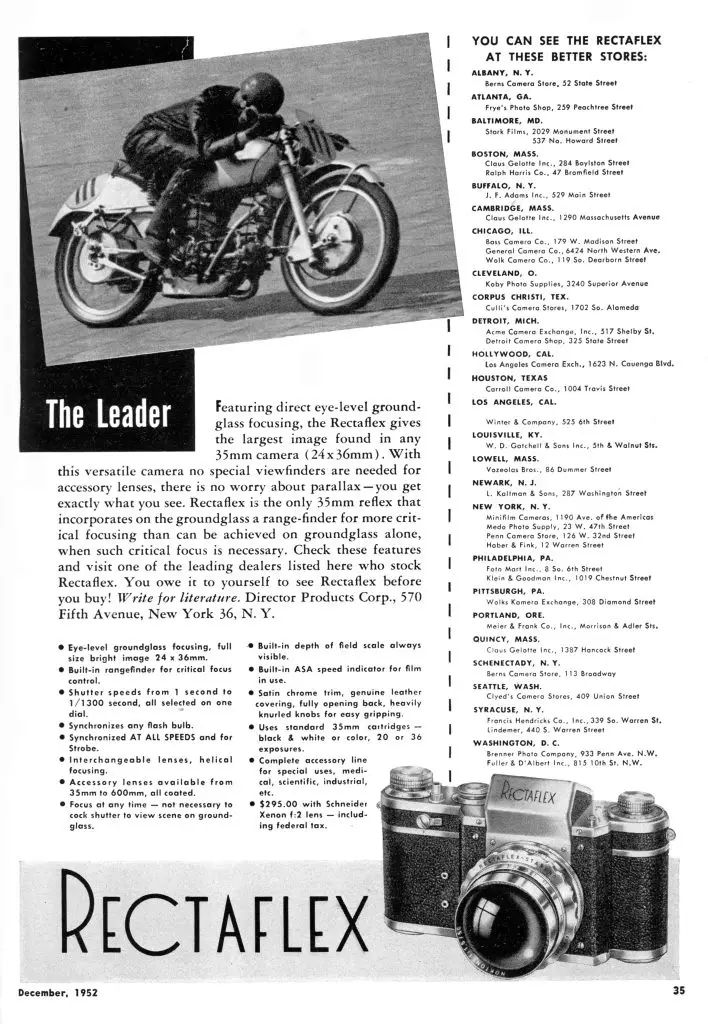

The Rectaflex was envisioned to be an international camera with exports all over the world, including the United States. In the US, Director Products Corp in New York City distributed the camera through dealers all over the country. The price of a Rectaflex with a Schneider-Kreuznach Xenon 50mm f/2 lens in 1952 was $295, which when adjusted for inflation compares to $2875 today, a high price but one someone would likely be willing to pay for an innovative new camera.

From 1948 when the first Rectaflex was produced to the end of the Rectaflex Liechtenstein’s production in 1958, less than 10,000 cameras were made, making them quite rare and highly valuable today. The Rectaflex was an innovative and gorgeous camera that when found in working condition had a selection of lenses that would have allowed them to make spectacular photographs.

This also means that asking prices are quite high. A quick eBay search for Rectaflex shows prices from just around $1000 to $10,999 for a Rectaflex Liechtenstein that is currently on sale. Of course, these are just asking prices as actual sold items are probably a bit less, but it’s safe to say that the cheapest Rectaflexes are going to be a significant investment for a camera that might not even work.

If you have an opportunity to pick one up at a price you can afford do it. If it doesn’t work, it’s still a piece of history that will look great on your shelf!

My Thoughts

Here’s a pro blogger tip for you, if someone ever asks if you’d like them to send you their Rectaflex to play with, there are only two acceptable answers, yes, and HELL YES!

Such was the case late in 2020 when talking to my friend Mike Novak. As part of the agreement that he would ship off his super rare camera, a caveat was that the camera wasn’t working correctly. Apparently some previous owner had thought it would be fun to take apart the Schneider Xenon lens, separating the focusing helix and not putting it back together correctly. As a result, turning the focusing ring more than half way caused the lens to split into two halves, rendering it useless. Mike said that if I could figure out how to put the lens back together, I could keep the camera for a while and play with it.

I was fresh off an earlier article this year called “Eleven Unfortunately Named Cameras” where I picked on the Rectaflex for it’s name which suggests it might be used for colonoscopies, but in reality, I was well aware at how special of a camera it was. Not only is it one of the only Italian made 35mm SLR cameras, it was historically significant as having the first pentaprism viewfinder in a 35mm SLR, and also featuring an early version of a rapid return mirror.

Instant Return vs Rapid Return Mirror: Most SLRs made from the 1950s and on have an instant return mirror. This is when pressing the shutter release immediately causes the reflex mirror to flip up out of the path of light through the film plane, and instantly flip back down after the exposure is made, minimizing the amount of time the viewfinder is blacked out due to the mirror being out of position.

The Rectaflex does not have an instant return mirror. It has what’s called a rapid return mirror in which the reflex mirror is still coupled to the shutter release, but it’s motion is directly controlled by pressure on the shutter release itself. As your finger presses down on the shutter release, a cable raises the mirror. Release pressure on the shutter release and the mirror comes back down. The speed at which the mirror moves is proportionate to the amount of pressure you put on the shutter release. Press or release it slowly and the mirror moves slowly.

The length of time the viewfinder becomes blacked out begins the moment you start to apply pressure on the shutter release, and only becomes usable again when all pressure is released from the shutter release, greatly increasing the amount of time the viewfinder is blacked out, compared to with an instant return mirror, in which the viewfinder is only blacked out for the duration the shutter is open.

Upon taking it out of the box, I was immediately struck with the quality of the camera. Mike had said the camera was cosmetically nice, but that was a bit of an understatement, as apart from a couple bright spots in the chrome finish and two very small imperfections in the body covering, the camera was pristine. If I was a Japanese eBay seller, this would definitely be TOP MINT+++!

With the lens mounted, the all brass and chrome camera weighs a not insignificant 972 grams. The body has rounded edges on both sides that were possibly influenced by a screw mount Leica, but the camera is not only wider than a Barnack Leica, but also wider than a Nikon F. The surface of the top plate is identical in height to a Nikon F, but the tip of the prism isn’t nearly as tall, giving the camera a shallow look, that combined with the angled edges of the mirror box, help mask the camera’s size.

The top plate is nicely laid out with controls in pretty logical locations. The rewind knob on the left is surrounded by a combination film reminder dial and flash synchronization delay setting. I had to read the Rectaflex manual to find out what this actually does as the abbreviations “Vac.” and “El.” are not something I am used to seeing. Above and to the right is a small release button for the lens mount. The flat top to the pentaprism has an engraving with a US patent number, suggesting this particular camera was exported to the United States.

To the right of the prism is the shutter speed dial which is split into fast and slow speeds. The fast speed dial has 1/25 to 1/1300 plus Bulb, and the slow speed dial has speeds from 1 second to 1/10. The slow speeds work differently than other cameras with a separate slow speed dial in that the slow speed dial also has a “0” setting that must be set when using the fast speeds. To properly use the slow speeds, you must first set the fast speed dial to 25 and then select an appropriate slow speed on the lower dial. Having the slow speed dial at anything other than 0 while also using a fast speed faster than 25 will cause problems.

Next is the cable threaded shutter release button and combined film advance knob and exposure counter. The exposure counter is manually reset and counts up from 0 with a fresh roll of film loaded.

The back of the camera has only a large swath of body covering on the door, the camera’s serial number in the upper left corner, the round eyepiece for the viewfinder, and a small serrated wheel which is used to rotate the slow speed dial on the top of the camera.

Beneath the camera are two raised feet, one containing the film compartment door release, and a centrally located 1/4″ tripod socket.

The foot opposite the door release serves no function other than to balance the camera. There is also a third, much smaller, foot beneath the mirror box for stability.

Accessing the film compartment is a matter of releasing the one lock on the bottom of the camera and pulling the whole thing off. In this regard, the Rectaflex is very similar to a Contax or Nikon rangefinder in that the entire back and bottom are a single unit.

Film transports from left to right onto a removeable take up spool which means that cassette to cassette transport is possible. The pressure plate is polished metal and there is a metal roller on the back of the door to aide in film as it travels through the camera.

On the bottom of the film door is a neat little sticker with various patent information that the Rectaflex was protected under in a variety of countries. I find this sticker to be interesting as I don’t know of any other camera that has this many patents printed anywhere on it, but also, the typeface of each country is the same elegant font as the one used for the Rectaflex logo on the prism.

Removing the lens requires a press of a small button on the top plate above and to the right of the rewind knob, and a gentle counterclockwise twist of the lens. I quite like the location of the lens release on the top plate as it allows you to hold down the release with your left thumb, while securely gripping the lens with your right hand, without having to contort your fingers to press release buttons like on some other cameras

The bayonet lens mount on the Rectaflex is unique to this camera and is impressively large, at least compared to others of the era like the Ihagee Exakta mount which was considerably smaller. Had the Rectaflex been more successful and more lenses developed for it, the large diameter of the mount would have allowed for f/1.2 and faster lenses along with heavy telephoto lenses, something the Exakta could not accommodate. With the Schneider Xenon lens attached, the lens feels secure with no play and just the right amount of tightness so as to inspire confidence, without being too hard to take back off.

The Rectaflex is a historically significant camera for a couple reasons, but perhaps the most important was the use of a pentaprism viewfinder. Although some prototype pentaprism SLRs existed prior to the Rectaflex’s release, none were commercially available until after this camera’s release. As is the case with any pioneering design, it would take quite a number of years to perfect the pentaprism, and the Rectaflex’s viewfinder clearly shows what an early pentaprism looks like.

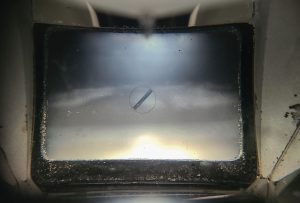

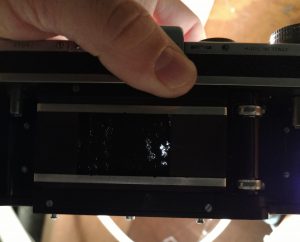

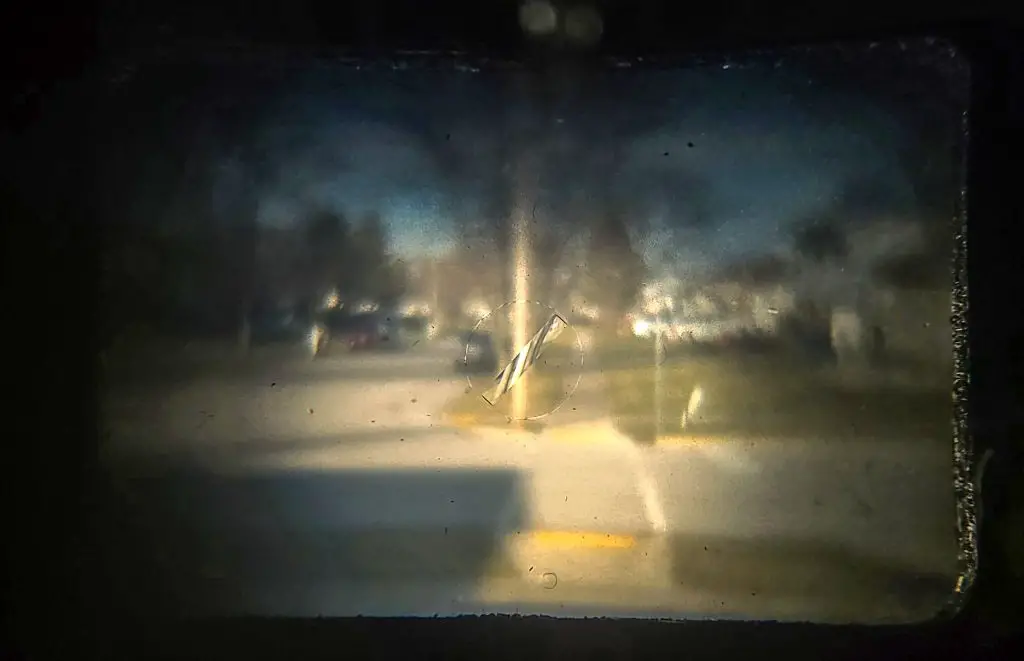

With the Schneider lens wide open at f/2, the ground glass viewing screen is dark, showing severe vignetting in the corners. Stopping the lens down makes viewing anything through the viewfinder almost impossible. With the camera in bright sunlight, the corners are dark, but indoors, they’re almost completely black. In the center of the viewing screen is a sort of split image focus aide, but not one that looks like anything I’ve seen. The focus aide is diagonal, but rather than being a line, it’s more like a thin rectangle. With the image out of focus, vertical lines are skewed at an angle. Rather than lining up two split images, as you turn the focus ring to bring the image into focus, the visible light passing through the diagonal rectangle rotates, until it lines up with the visible information outside of the rectangle.

Take a look at the two images above through the Rectaflex’s viewfinder. I show the same image both in and out of focus, so you can better see what the angled focus aide looks like. Notice how the vertical utility pole becomes diagonally skewed when out of focus.

Whenever I do these reviews and take a through the viewfinder photo, I use my smartphone in manual mode as I’ve never found any other digital or film camera that can get close enough to the tiny viewfinders on most cameras to capture an image. The Rectaflex was very difficult to get a good image of, even in my camera’s “pro” mode.

Although the viewfinder is dark, it’s worth noting that a photographer using this camera in 1948 when it was first released would have been very impressed at their ability to see a through the lens image at the correct orientation, and would have likely forgiven the lack of brightness. The Rectaflex certainly redeemed itself in other areas, but by how much? Let’s load in some film and find out!

My Results

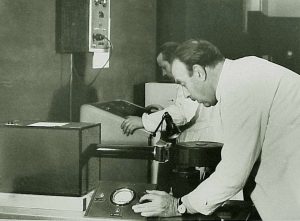

This camera was graciously loaned to me by fellow collector Mike Novak with the understanding that the lens had separated at the helix. Someone had previously opened the lens and couldn’t get it back together. Although a rare camera, the lens is a pretty common Schneider-Kreuznach Xenon which isn’t that complicated to disassemble, so I thought I should be able to get it back together.

I was right, as getting the two halves back together was largely just a matter getting the helix threads in just the right position so that when I tightened the set screws down, the lens was correctly at infinity. I did not take any images of this process as it was entirely trial and error, involving me screwing it together, and seeing if the holes lined up. Once I had it right, the lens correctly stopped at infinity with the infinity symbol lining up with the index mark.

Although I was successful at repairing the lens, I noticed that it had a large amount of haze in it, and also that the second shutter curtain (the one that you see with the shutter cocked) had more holes than a piece of Swiss cheese. There were large areas where the rubberized coating had totally flaked off, making for hundreds of little pinholes. There’s no way this shutter wouldn’t have light leaks, but not having a lot of opportunities to shoot a Rectaflex, I figured I would do my best to minimize the time the shutter was cocked before I would fire it, and when it was, to shield it from sunlight as much as I could.

With so many unknown variables with this camera, for my first roll, I loaded in some bulk Arista.Edu 100 black and white film that had been exposed on the edges while still in the can. Although partially exposed, this film was still good for testing as I had a lot of it and if I ended up wasting some, it was no big loss.

The first roll was a mixed bag. I noticed that I missed focus on nearly every shot where I focused to infinity, but strangely, closeups and medium distance images turned out reasonably OK. There were visible light leaks from the holes in the curtain, but those only seemed to show up in instances where I was shooting in bright sunlight. Finally, in a few images, there appeared to be a light leak on one side of the image, but considering the age and rarity of this camera, I still felt successful, so I loaded in a second roll of film, this time some expired Kodak Gold 100.

Sadly, the poor condition of the shutter continued to deteriorate with the second roll causing an issue where the second curtain would not completely close upon exposing the image, leaving a large overexposed stripe on one side of the image. This is what likely caused the light leaks I saw in a few images from the first roll.

I also missed focus quite a bit more on this roll, likely because the first roll was shot in bright sunlight where I was able to stop down the lens to increase my depth of field, but with this second roll shot in the low light of winter, I had to open the lens more, losing the benefit of greater depth of field. The lower light helped to reduce the pinhole light leaks from the curtains, but that wasn’t enough to improve what was a complete disaster of a roll.

Thinking that maybe I just didn’t try hard enough on that roll, I figured with the rarity of the Rectaflex, it was worth one more roll, so I tried again, this time with some Fuji 200, and got more of the same. Sadly, it would appear that this camera wasn’t going to get any better, no matter how hard I tried.

Looking past the many obvious conditional issues of this camera, I have no doubt that the Schneider Xenon would have delivered anything less than razor sharp images corner to corner with excellent contrast and color reproduction. I’ve shot enough versions of this lens on Kodak Retinas and in various SLR mounts to know that this is a quality lens.

It is obvious that this camera needs a complete restoration to be in proper working order. I recently learned my lesson in a recent post where I had to eat my words about declarations I made about a less than perfect Zeiss-Ikon Contessa 35 requiring me to revisit that review with a better working example. If I ever get an opportunity to shoot a perfectly working Rectaflex, I’ll definitely do a second look with that camera too, but until that day comes, I’ll do my best to extrapolate what a working Rectaflex might have been like to use.

When the Rectaflex was first built in 1948, how an SLR should look and work was still up in the air. This camera was pioneering in it’s use of a pentaprism viewfinder and a rapid return mirror. A rapid return mirror differs from an instant return mirror as the length of time in which the viewfinder is blacked out is much longer because it is coupled directly to the movement of the shutter release button.

While it might not seem like a big deal reading about it, in use, this is a big problem as you lose sight of your composed image throughout the entire process of pressing and releasing the shutter. When you consider early photographers did not like SLRs because of viewfinder blackout, the Rectaflex’s solution does not solve the problem. In fact, I’d say it makes it worse as in order for the shutter release to have enough “action” to control the entire movement of the mirror, it requires a fairly long press to actuate the shutter. You could try to minimize the length of time it requires to fully press the shutter release by pressing down on it faster, but as you press harder on the shutter release, you increase your chances of motion blur by shaking the camera.

My struggles continued beyond the shutter release as I had difficulty loading film into the camera as I found the take up spool to have an excessive amount of play in it. I’ve shot many cameras with removable take up spools before, such as the Ihagee Exakta and Zeiss-Ikon Contax and in those cameras, as long as you get the film properly threaded onto the spool, you can close the camera with little issue. For reasons that I’ll acknowledge might have been user error, in all three rolls of film I loaded into the Rectaflex, I struggled to get the film to advance through the leader. With most cameras, I can securely attach the film leader to the spool only having to fire off 1 or 2 shots of film before I am confident the film will transport correctly, but with the Rectaflex, it took three times as much.

It is clear this camera has serious issues with the shutter, there’s some haze in the lens, focus collimation might be off, and maybe there’s something amiss with the film advance so maybe I’m being a little too critical of this 72 year old SLR designed by an Italian lawyer.

With all the negativity out of the way, I will end this review on a high note and say that this could perhaps be the best looking SLR ever made. In the time since it arrived in the mail and publishing this review, I have handled this camera for many hours, admiring it’s gorgeous looks and excellent tactile feel.

Aside from the long throw of the shutter release, the ergonomics are very good, which is extra impressive considering this camera predates any SLR with what we’d consider today to have a modern interface. The camera has a great feel in your hands and despite being nearly three quarters of a century old, does not creak, or otherwise suggest that it was cheaply made. I do not know the history of this particular example, but both the body covering and the original chrome plating all survived remarkably well, and although I only have this one sample, looking at pictures of other Rectaflexes online, I do not recall a single ugly example, suggesting that they all hold up pretty well.

The joy in collecting and using old cameras is in their variety and quirks. If every camera was a Nikon FM, this hobby would get boring quick, so if you’re looking for a historically significant camera that’s really well built, and looks gorgeous on a shelf, this is the camera for you. If you are a collector with a budget that would allow you to buy a Rectaflex, do not let anything I’ve said here dissuade you from buying one. Make no mistake, this is a special camera. I just do not recommend taking it out for more than one or two test rolls, as it’s not a whole lot of fun to use.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rectaflex

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Rectaflex

http://www.pentax-slr.com/108413508

https://retinarescue.com/rectaflex.html

http://bencinistory.altervista.org/002Beng%20Cameras%2047/02A%20RECTAFLEX%20eng.html

http://www.arvaliastoria.it/public/post/rectaflex-428.asp (in Italian)

http://photographyandspeeches.blogspot.com/2013/02/cera-un-volta-la-rectaflex.html (in Italian)

Very informative and well researched article on the Rectaflex! I entered the name online and your article popped up. My dad worked for Kodak for many years and before that, another company called Victor Animatograph Corporation. Dad was loaned to the US Govt during WW2 to be the liaison for all photographic and aerial films for the military. He made a number of trips abroad during that war. He was the director of planning for the Kodak pavilion at the 1964-65 Worlds Fair in NYC. My father was an avid travel and family photographer who was always taking movies and photos with different equipment. He had a Rectaflex on his shelf, obtained who knows when and where, which I still have, he knew everybody in the photo business (I remember we got a Christmas card every year with photos from Victor Hasselblad.). After reading your article I’m going to go find my Rectaflex and check the serial number for fun. ( I just subscribed to your feed)

Just acquired a Rectaflex 1300 (27,… serial) with SOM Berthiot Flor 50/2.8. I had one years ago but was ‘forced’ by a local dealer to sell it back when he decided to start collecting again! (One day I will ask you for a favour…) I’d used that one when compiling a book on the prism SLR. (Blurb – Andrew Fildes). So it was nice to get one back and in very good condition. In Australia but it’s probably bought in the USA as it has the US patent numbers engraved on the back.

There are a couple of things worth noting. This one needs work on the slow speed governor and we discovered that it has jewelled escapments like a watch. Until now I thought that only Alpa had done that. But the lenses…! Every lens supplied was remounted into Rectaflex’s own lens barrel and there were many, many 50mm choices. Only four for the early models but eventually twenty-two 50mm lenses were offered over the seven years from Italian Filotechnica and Galileo to Angenieux, Zeiss and Voigtlander. The Voigt 5cm f1.5 Nokton is probably the most valuable. Every one, as you noted, rebuilt into a Rectaflex body. That is commercially insane.

Most are coded as well. The body alone was tagged STARE (STAndard REctaflex). The a letter was added for the lens so a camera fitted with an Angenieux was a STA RE A. Some refer to all Rectaflerx as a STAREA but this is incorrect. Mine with the Berthiot is a STAREB. In the early models the lens was calibrated to the camera body and the code engraved on the lens barrel. Later a shorter code was used and the engraving dropped, as was the individual calibration.

I once wrote a series of magazine articles on photo industry disasters and included it. Great camera and hopeless production and marketing. Must rewrite the series and put it online – Fotochrome anyone?

Good Afternoon, Mike!

I am repairing a Rectaflex 1300, on which the shutter curtains have detached and one of the shutter shafts had seized up solid. It is now fixed and working (not tested with film, as yet), but my main surprise was that the shutter curtains on this example are in actual rubber (Pirelli ???) rather than rubberised cloth. Judging by the prestine state of all the screws the camera had not been disassembled before now.

Have you or anyone else seen or read about any Rectaflexes having real rubber curtains?

MIkhail.

Great information! Popped up her because i’m trying to find information and value for my late dad’s Rectaflex B 2000 (serial 250x) camera. Not many B 2000’s in sale today…