This is a Rollei 35 T, a premium 35mm scale focus camera, built by Rollei-Werke Franke & Heidecke in Singapore starting in 1974. The Rollei 35 T was a later evolution of the original Rollei 35 which was first introduced in November 1966. When it was released, the Rollei 35 was the smallest full frame 35mm camera ever made, a claim that rarely changed even in the years after it was discontinued. The entire Rollei 35 series was very popular, staying in production until 1981 with only small changes to the original formula. Several years after the last of the original models was discontinued, the camera was resurrected as several special edition collector’s models throughout the 1990s.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 40mm f/3.5 Rollei Tessar coated 4-elements

Focus: 3 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Scale Focus with 40mm Projected Frame Lines

Shutter: Inside the Lens Compur Leaf

Speeds: B, 1/2 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: Coupled CdS Cell w/ top plate match needle

Battery: 1.35v PX625 Mercury Cell

Flash Mount: Hot shoe and M and X Flash Sync (all speeds)

Weight: 328 grams

Manual (Similar Model): https://www.cameramanuals.org/rolleiflex/rollei_35.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Rollei 35 T, like the entire Rollei 35 series was a miracle of engineering and quality. What Franke & Heidecke was able to cram into such a small and light weight package, while still delivering outstanding quality and workmanship in a full frame camera is amazing. Although loaded with quirks that definitely require a user manual for the first time user, once you get the hang of using it, will deliver top notch photographs every time. These cameras were highly regarded and very popular when they were first sold, staying in production (including special editions) for nearly 30 years for good reason as they are one of the coolest cameras ever made. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 20% | |

| Bonus | +1 for outstanding quality in such a small form factor | ||||||

| Final Score | 14.2 | ||||||

The name “Rolleiflex” or simply “Rollei” refers to a brand of cameras produced throughout a large part of the 20th century by a company called Werkstatt für Feinmechanik und Optik, Franke & Heidecke (or Franke & Heidecke for short). The company was originally founded in 1920 by two former Voigtländer employees, Paul Franke and Reinhold Heidecke in Braunschweig, Germany.

Their first products were a line of plate film and roll film stereo cameras called the Heidoscop and later the Rolleidoscop. These cameras all had a similar form factor of stereo “taking” lenses and a third viewfinder lens in the middle. All three lenses were arranged horizontally and generally used Zeiss lenses and Compur shutters.

Franke & Heidecke’s stereo cameras were a huge hit and by 1927 allowed the company to expand their portfolio and try out some new designs. By 1929, the company’s first twin lens reflex (TLR) called the Rolleiflex was released. Although twin lens designs had existed before the Rolleiflex, Franke & Heidecke’s new camera would set the standard for which all TLRs would follow, both from a design and functionality standpoint.

By the early 1930s, the Rolleiflex would become an immediate hit and would have unparalleled success over the next several decades. Like the Leica II rangefinder built by Ernst Leitz, the Rolleiflex would become an often copied camera, with models produced by a huge number of German, American, and Japanese companies. Some Rolleiflex clones copied the design very closely, and others changed the formula a bit, but they all retained the same basic shape and form factor.

One of the reasons that Franke & Heidecke was so successful was because of the leadership of both Paul Franke and Reinhold Heidecke. Franke had a keen business ethic which under his leadership allowed the company to secure strong bonds with suppliers and distributors alike. He ran the business efficiently and allowed the business to grow. Reinhold Heidecke on the other hand was responsible for the engineering and design that made the company’s cameras successful. With the combined leadership of both men, Franke & Heidecke was well suited to develop, create, market, and sell their products all over the world.

Unfortunately, in 1950, Paul Franke would fall ill and suddenly pass away, leaving the business to his son, Horst. The younger Franke lacked the leadership and business know-how that his father had, and throughout the 1950s would make several business decisions to the detriment of the company. Buoyed by the success of the Rolleiflex and the engineering prowess of Reinhold Hedecke, the company still remained profitable despite it’s leadership woes.

By the end of the 1950s, Franke & Heidecke’s success started to slow. Professional and advanced amateur photographers already had their Rolleiflexes, and with increased competition from the Japanese camera industry and new 35mm SLRs from Nippon Kogaku, and quality professional cameras from Hasselblad, sales started to stagnate.

In the early 1960s, Franke & Heidecke started to release new products like a slide projector and 16mm camera, but nothing that made any significant dent in the marketplace. It was clear that the company had no good direction for the future and needed outside help.

In 1964, the company now officially called Rollei-Werke Franke & Heidecke, sought the advice of outside sources. A 38 year old German physicist named Heinrich Peesel produced a detailed report of where he thought the company should head which impressed Rollei leaders so much, that he was offered a position as Chairman of the Rollei board of directors.

Peesel’s approach was aggressive and involved a complete 180 of the company’s direction from medium format TLRs into several other markets to which the company had little to no experience. It is said that Peesel reviewed a large number of ideas for new products that the company had thought up, and of those, only three were built – a Rolleiscop slide projector, a medium format 6×6 SLR called the SL66 which competed with the Hasselblad 500C, and a 35mm miniature camera called the Rollei 35.

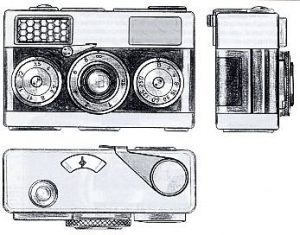

The Rollei 35 was designed by a German engineer named Heinz Waaske who formerly worked for Wirgin, and in 1954 built the Edixa Reflex SLR. While working for Wirgin, Waaske became interested in compact cameras, and in 1962 released the subminiature Edixa 16. This camera produced 12×17mm images on unperforated 16mm film loaded into special cassettes. The Edixa 16 is notable in the history of the Rollei 35 not only because it would lead Waaske down the path to creating it, but it also featured separate controls for shutter speed and aperture on two separate dials, a design he would later reuse on the Rollei.

Shortly after the release of the Edixa 16, Waaske began putting together drawings for a compact 35mm camera that would use some of the concepts of the Edixa 16. His goal was to create the world’s smallest full frame 35mm camera. In his spare time, Waaske built a prototype that had a body no larger than a pack of cigarettes, a collapsible lens, and a selenium exposure meter.

An early mockup of the camera had a Steinheil Cassar 40mm f/3.5 lens and Metrawatt meter. Both Steinheil and Metrawatt were suppliers to Wirgin, so Waaske was able to acquire samples without much difficulty. Waaske’s choice of a 40mm lens was out of necessity as it allowed for the lens to be physically smaller, while still being able to cover a full 24x36mm frame. At the time, the choice of a 40mm standard prime lens was not common, but would later prove to be popular among many other manufacturers such as Konica, Canon, and many others.

One of the biggest challenges for Waaske’s new camera was the shutter, as there didn’t exist anything small enough to fit inside the camera while keeping it as small as he wanted. This required a shutter to be designed from scratch as two separate pieces. The clockwork mechanics were attached separately to the body, connected to the shutter blades located inside the sliding lens tube via a coupled shaft. Cocking the shutter would disengage the coupling to the shutter blades, allowing the lens to be collapsed.

After working on his new camera in his spare time over the next two years, Waaske was ready to present his idea to his boss, Heinrich Wirgin. Wirgin was less than thrilled. He was reportedly unhappy that Waaske used Wirgin’s workshop and parts suppliers for his own project, and firmly rejected the idea of producing the camera. This soured Waaske’s relationship with Wirgin and soon after he would leave the company.

Now unemployed, Waaske demonstrated his prototype to management at both Leitz and Kodak in the hope they would be interested in producing the camera, but both companies turned him down. In January 1965, Waaske would begin working for Rollei, but after repeated bad experiences showing his camera to other companies, this time he kept it to himself.

Less than two months later, in a chance meeting with Heinrich Peesel, Waaske would reluctantly show him his prototype. Peesel loved the concept and said this was exactly what he was looking for and ordered continued development of the camera. Peesel’s only demand was that all parts of the camera be built by Rollei suppliers, so the Steinheil lens was out and a Carl Zeiss Tessar was in, the Metrawatt meter was replaced by a Gossen unit developed specifically for Rollei, and the proprietary shutter was built by Compur.

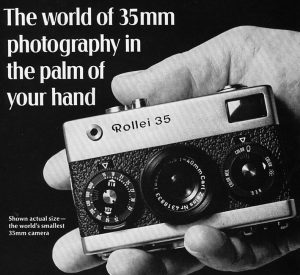

Now called the Rollei 35, the camera was announced at Photokina in September 1966, and when it was released in November 1966, the world was in the midst of a high level of popularity for 35mm half-frame cameras. These cameras were popular for a number of reasons, one of which was their more compact size. With the release of the Rollei 35, the world saw that full frame cameras could also be small. While it’s not fair to say that the Rollei 35 singlehandedly caused the downfall of half-frame cameras, it likely was a factor, as sales started to slow in the half-frame segment in the year following it’s release.

When it was released, the Rollei 35 sold for $189.95, which when adjusted for inflation compares to a little over $1500 today. This would have been quite a high price for a scale focus, fully manual camera, with no automation, and only a match needle exposure meter. The camera’s most appealing features were without a doubt it’s compact size and Rollei’s reputation among professional photographers.

The Rollei 35 was warmly received by the public and sold well. According to the serial number database at rolleiography.com, between November 1966 and December 1971, more than 300,000 units were sold. In June 1971, production of the Rollei 35 would be shifted from Germany to Singapore to take advantage of more favorable production costs.

Building anything in Germany was expensive, and in an effort to keep costs down the decision was made to outsource production. For the remainder of the year, production continued in both countries, but starting in 1972, all future models would be produced in Singapore, with the exception of some limited edition models from the late 1980s and 90s.

Between June 1971 and August 1974, another 200,000 Rollei 35 cameras were produced, but in July 1972, the company struggled to get enough Zeiss Tessar lenses, so around 30,000 models equipped with a Schneider S-Xenar 40mm f/3.5 lens was substituted. In April 1973, Rollei stopped using Zeiss Tessar lenses produced by Carl Zeiss, and licensed the lens formula from Zeiss and produced the lenses themselves. Although no longer made in Germany by Zeiss, Rollei produced Tessar lenses are considered to be optically just as good.

From 1966 to 1974, the Rollei 35 stayed largely the same with only minor incremental updates. In September 1974, the first major change to the camera came with the release of the Rollei 35 S, which upgraded the 4-element f/3.5 Tessar to a 5-element f/2.8 Sonnar. A model with an improved lens was planned as far back as 1967, but a combination of the move to Singapore, plus early variants producing unsatisfactory image quality resulted in the upgrade being pushed back several times.

When it was released, the new model was called the Rollei 35 S, and the Tessar version was renamed the Rollei 35 T. Some sources online incorrectly claim that the name change adding the S and T happened at the same time as the move to Singapore, but this is not correct.

Both the Rollei 35 S and 35 T continued to produced together until February 1980, when they were superseded by Rollei 35 SE and TE models which upgraded the exposure system with LEDs instead of an analog meter. The “E” in the model name stood for electric, and not “special edition”. Production of those models would continue until September 1981, at which time, both “premium” Rollei 35’s were discontinued in favor of less expensive models.

Throughout their entire production run from 1966 to 1981, over 1.5 million cameras were built making the Rollei 35 one of the longest lived and best selling cameras of all time, an impressive feat for a premium camera with a quirky interface that lacked modern conveniences such as auto exposure or a motorized film transport.

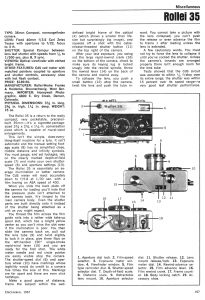

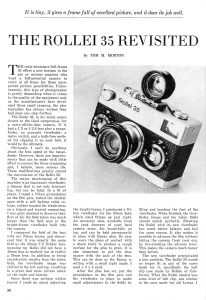

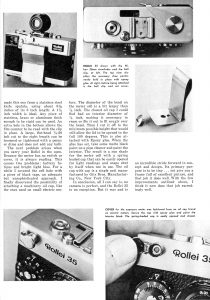

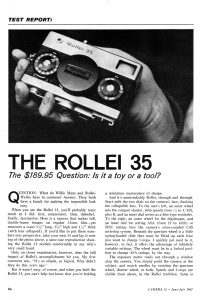

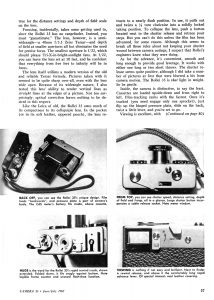

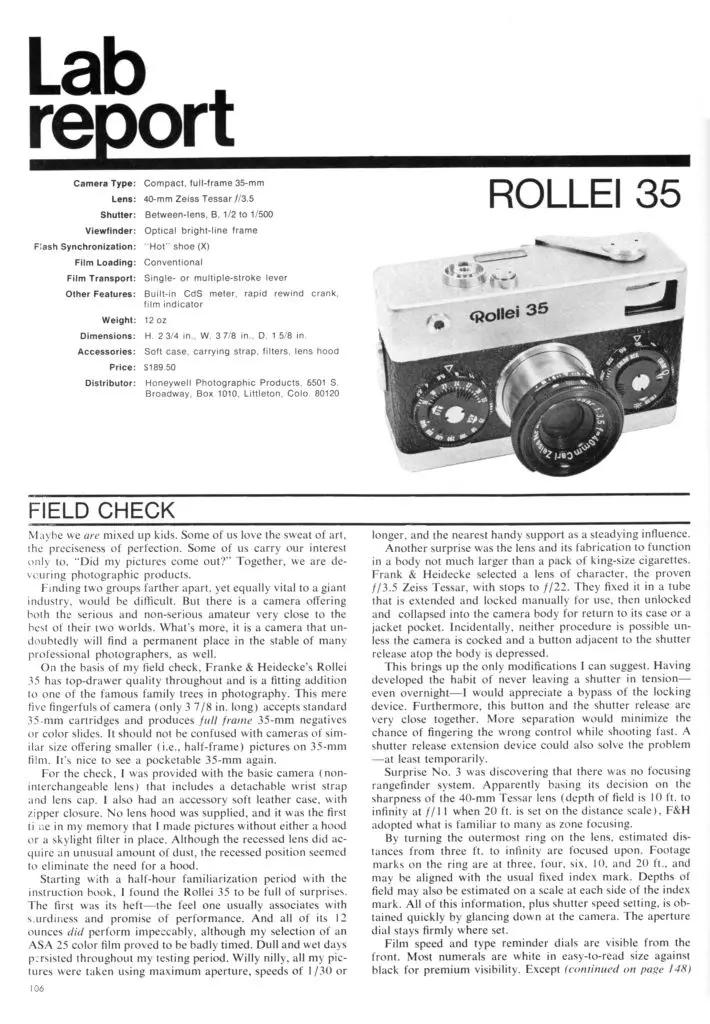

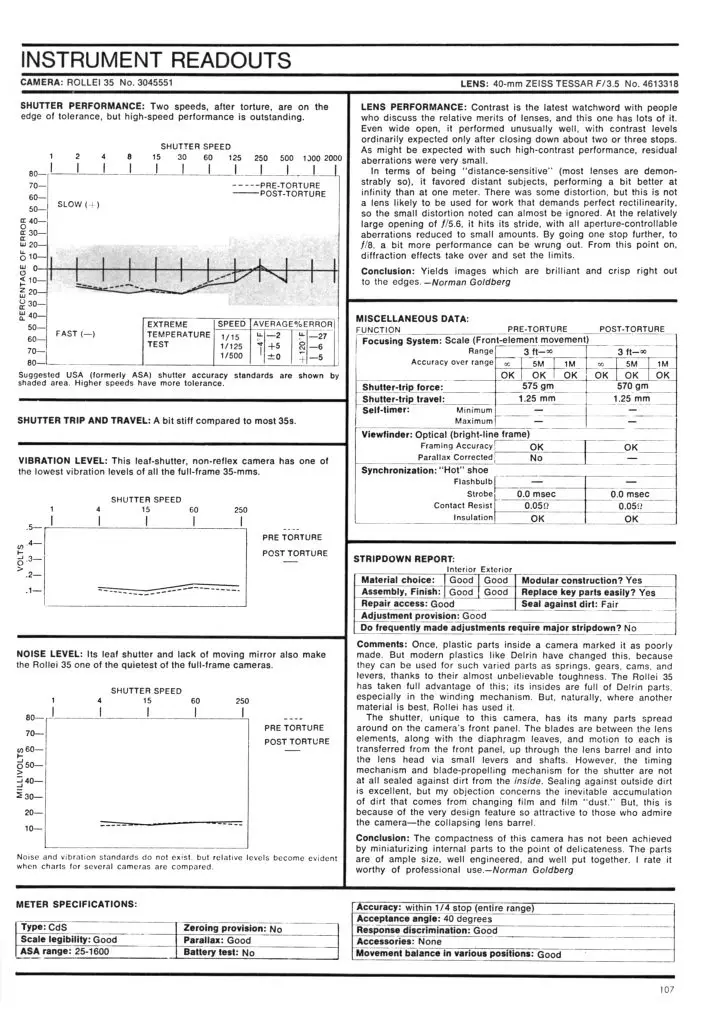

While researching this article, I found a number of articles which I have included in the gallery below. The first is from the June/July 1967 issue of Camera 35, and the second from the December 1968 issue of US Camera.

This Lab Report is from the March 1969 issue of Modern Photography and is much more technical in nature. On the first page is a field test describing the camera’s usage and it’s strengths. On the second page are several tests of the camera’s lens and shutter, along with some technical notes by Norman Goldberg. In the event you don’t feel like reading through it all, I’ll just summarize that they liked the camera!

With the success of the Rollei 35, a less expensive model called the Rollei B35 was produced from October 1969 to September 1978 with a 3-element Triotar lens. Other than a sharing a similar sized body and the Rollei name, these economy cameras share little in common with the “premium” Rollei 35s. The final model, called the Rollei 35 LED sounds like it might be part of the main family, but is in fact, an economy model, with an LED meter display within the viewfinder.

Regular production of the Rollei 35 would end in 1981, but in 1986, new owners of the Rollei name sourced up all the manufacturing tools and parts from Singapore and brought them back to Germany and launched a new, limited production Rollei 35 Classic line. Within this line were a number of custom made special editions. Many of these cameras have gold or platinum plating, some were made to celebrate Rollei’s 75th Anniversary, one was made with all metric markings, and eve one with a blue and gold flake paint job. While there were several different labels applied to these special editions, they are all considered part of the Rollei 35 Classic line.

According to rolleiclub, several thousand of these were produced between 1986 and 1998. A different source on camera-wiki suggests Classic editions could be custom ordered as recently as 2014. Even without the 2014 date, a production run from 1966 to 1998 to a mostly unchanged model is a run of 22 years, making it one of the longest lived single camera models of all time.

Today, Rollei 35 cameras are very popular. A combination of their history, design, and quality add to their appeal on top of which, these are excellent cameras to use. Whether you are a collector just looking for a nice piece to display on a shelf, or someone who will load in some film and take one out shooting, the Rollei 35 line has something for everyone.

My Thoughts

You don’t have to shoot film or collect cameras for very long to hear about Rollei cameras. The Rolleiflex twin lens reflex, and it’s lower spec Rolleicord are two of the most influential and popular cameras ever made. Say the name “Rollei” around a group of film photographers and most of them will immediately think of one of the many medium format TLRs produced between 1929 and 2000.

Although by far the company’s most popular style of camera, medium format twin lens reflexes were not the only cameras to bear the Rollei name as the company had several lines of 35mm cameras too. Back in April 2018, I reviewed my first 35mm Rollei, the Rolleiflex SL35, a nicely built 35mm SLR with a Zeiss Planar lens and a clean interface. Unlike my feelings about Rolleiflex TLRs, I found the experience of using the SL35 to be sterile. I didn’t have any complaints about the camera, but there was nothing special that made it stand out from the rest.

Fast forward to the summer of 2020, and my friend and fellow collector Anthony Rue and I were talking about favorite cameras and he mentioned how much he loved his Rollei 35 T. Upon telling him that was a camera I hadn’t yet had a chance to shoot, he immediately asked for my address and sent it off to me. I was aware of these cameras, and knew they had a strong following, but prior to that conversation, I never had much of a strong desire to acquire one for myself. I had no reason to doubt Anthony’s love for this camera, and I figured it would be a well built camera that made great images, but how good could it really be?

When the camera arrived, my first reaction was how small it was. When I wrote my review for the Minox 35 ML, I briefly mentioned how the Rollei 35 was the smallest full frame 35mm camera for years before the original Minox 35 EL was demoed at Photokina 1973.

The Minox 35 certainly is small, but it has a plastic body that doesn’t feel like a precision instrument with Zeiss optics and German build quality.

I could immediately tell the Rollei 35 was a marvel of engineering. Anthony assured me this example was in perfect working order so there was no reason not to immediately load in some film and take it out shooting, but then I realized that I couldn’t figure out how to use it. In order to make these cameras as small as German-ly possible, Heinz Waaske got very creative with some of the camera’s controls and because of that, my first tip for using a Rollei 35 is to read the manual (or this review).

Looking at the camera’s top plate, we have have the film advance lever on the left. With the lens collapsed like in the image to the right, you won’t ever be able to advance this lever because in order to collapse the lens, someone previously already advanced it. With the lens collapsed, the shutter is already cocked and the film already advanced, so that is why you cannot advance it again. If this is your first time interacting with a Rollei 35, you’ll definitely want to extend the lens first, before attempting to press the shutter release.

Next is a rectangular window with the exposure meter readout. A white needle in this display moves based on the amount of light the CdS meter detects. Proper exposure is obtained by turning any combination of shutter speeds and aperture f/stops, so that the orange needle with the circle on the top lines up perfectly with the white needle.

To the right and above the meter is the cable threaded shutter release, and a smaller button that is used to collapse the lens. The shutter release will remain locked at all times while the lens is collapsed.

Before shooting the Rollei 35, you must remember to extend the lens all the way. Due to the design of the shutter, it must have already been cocked before the lens was collapsed, so by extending it, the camera will immediately become available to shoot.

There is nothing special you need to do to extend the lens, other than grip it and pull it out. Some kind of gasket provides enough resistance to keep it in place when collapsed. Once the lens is pulled as far as it will go, a small clockwise twist is required to lock it into position. Make sure you do this, as failure to lock the lens will prevent the shutter release from working.

Once you are done shooting and wish to collapse the lens again, make sure you wind the film advance lever, then press the small button on the top plate above and to the left of the shutter release, and while holding it, twist the lens counterclockwise to unlock it and gently push it back into the body.

The camera’s back is mostly uncluttered, with only the rectangular eyepiece for the viewfinder, a rewind release switch, the back handle of the top mounted film advance lever, camera serial number, and a small port for accessing a meter adjustment screw. Swiveling the rewind switch a full 180 degrees puts the camera into rewind mode, and causes the little handle to protrude above the top plate, cleverly blocking the film advance lever from being wound while the camera is in rewind mode.

The bottom of the camera is quite cluttered with what I believe to be the only 35mm camera with a flash hot shoe on the bottom. Opposite of the hot shoe is the rewind knob with fold out handle that has a tooth and a notch in the center of it’s shaft, that when properly engaged, allows you to rewind film.

In the center is the 1/4″ tripod socket with a small window for the automatic resetting exposure counter. The counter resets when opening the camera to load film, which is done first by sliding the trapezoid release, between the counter and hot shoe.

Once you release the lock on the bottom of the camera for the film compartment, the entire back and bottom come off as one piece, revealing the entire film compartment. The film pressure plate is bottom hinged and folds out of the way for loading film.

Film transport is from right to left onto a fixed double slotted take up spool. The spool rotates in the direction of the arrow and with the shutter not cocked, you can manually turn it with your finger, but only one full revolution. Once you’ve rotated the spool, it will lock into position, and you should not try to force it any farther. At this point, one of the two white slots for the film leader should be visible, allowing you to easily attach it.

With the leader attached, wind the camera at least one full rotation and fire the shutter, ensuring the film is correctly traveling and won’t slip off, and then replace the film back. With the back on, swing down the rewind release so that it is pointing down, and make sure you securely latch the film door lock on the bottom of the camera.

Continuing with the Rollei’s practice of squishing every feature into places you don’t expect to find them, the camera’s battery compartment is hidden behind a metal disc at the top of where a cassette of film would go. This metal disc has four notches in a plus pattern which require a coin to remove, revealing the battery compartment for a single PX625 battery.

While it’s understandable to put the battery here as the camera needed to be as compact as possible, this means that if the battery were to ever die with film loaded, you’d either have to change it in a film changing bag, or rewind a partial roll of film before swapping out the battery. In 1979 with the release of the Rollei 35 SE and TE, the type and location of the battery would be changed to a PX27 located under a panel on the top plate of the camera.

Note about Mercury Batteries: The Rollei 35 was designed for a 1.35v mercury battery which is no longer made. Modern equivalents are usually alkaline which have a higher voltage. Some cameras can automatically compensate for the increased voltage, so that an alkaline equivalent can be used in it’s place, but not the Rollei 35. Using a 1.5v mercury battery won’t damage the camera, but it will throw off the meter readings, making it unreliable. If you plan on using the meter on this camera, you’ll either need to send the camera to a specialist who can modify it to use 1.5v batteries, or use something like a PX625 Wein cell that is the correct voltage. For this review, I did not use the meter, and shot the camera using Sunny 16.

The front of the camera has two round dials on each side of the lens. The one to the left has both the ASA film speed setting and the aperture control. Looking at the front of the camera, changing film speeds is done by rotating the inner black disc and aligning the arrows to whatever ASA or DIN film speed you have loaded into the camera. This is only needed for the meter, so if you don’t plan on using the meter, then this step can be skipped..

The aperture is controlled by turning the entire outer ring and looking at the numbers pointing the top plate of the camera. Before you can turn the dial however, you must first press in on the little switch beneath the dial, which is there to lock the dial into position, eliminating any chance you could accidentally change f/stops.

The small round window to the left of the Rollei logo is the CdS exposure meter, which was made by Gossen, specifically for the Rollei 35.

Shutter speeds are changed with the dial on the right side of the lens. Like the aperture wheel, shutter speeds can only be seen from the top. If you look at the image earlier in this review of the top plate of the camera, you can see both the shutter speeds and f/stops that were selected when I took the photo. In the center of the dial is a film type dial which is nothing more than a reminder. Unlike the aperture dial, there is no lock on the shutter speed dial.

The viewfinder is large and very bright. Without any focus aides like a beamsplitter, nearly 100% of the light from the outside makes it to your eye, making for an extremely bright viewfinder that is easy to compose in poor light. A set of 40mm frame lines are there with parallax correction marks for minimum focus are there to help you compose your image. As a wearer of prescription glasses, I had no trouble seeing all four sides of the frame lines without having to press my face into the eyepiece.

It bears repeating, the Rollei 35 is a marvel of engineering. Even without loading any film into this camera, it is clear that the Rollei 35 is special. Heniz Waaske was right to be proud of his invention and keep promoting it to Wirgin, Leitz, and Kodak before hitting a homerun with Rollei. Without that level of persistence, it likely would have never been produced. With my review heavily leaning towards being a positive one, does a clever and compact design produce images worthy of a positive review? Keep reading.

My Results

After spending some time reading the Rollei 35’s manual and familiarizing myself with the controls, I felt confident enough to load in some film and take it out shooting. The first roll was fresh Kodak ProImage 100 which I took on a late summer trip to Brookfield Zoo, near Chicago. This is a film that I first started using in early 2020 as my preferred 100 speed color film. Not that there’s a lot of options for 100 speed color film, but ProImage 100 is quite a bit cheaper than Kodak Ektar 100, and produces more natural colors. In the short time I’ve used this film, I have learned that it shines in bright sunlight as cloudy overcast days produce unappealing muted colors lacking in contrast.

For my second roll, I loaded up some bulk Kodak TMax 100 and took it around town just before Christmas 2020.

It didn’t take long after receiving this camera in the mail from it’s owner for me to see the appeal of the Rollei 35 T, but after seeing the results from both the color and black and white rolls of film, only then did I realize how incredible of a camera this is. I’ve shot many cameras that have a Zeiss Tessar lens, and they almost always come out nice, but the example on this camera seems to have a little extra something as I was consistently amazed at the sharpness and level of detail to the images.

Looking at the images full screen without zooming in, especially the black and white ones, these almost look digital. Sharpness and contrast are a tick above images from other Tessars, with these having more “pop” than I am used to seeing. In the image of the sunlight shining through the leaves, they seem to almost jump out at you, and in the black and white images of Homewood Florist, the mural on the side of the building is actually more vibrant here than it is in person.

In 1974, the Rollei S was released with an upgraded f/2.8 Sonnar lens, and despite having an extra lens element and half a stop of extra speed wide open, I can’t imagine how these images could have looked any better. For photographers then and now on the fence trying to decide if the extra money is worth it for the “better” lens, I’m going to go out on a limb here and say, save your money, get the Tesssar and using your savings on more film.

I loved using the Rollei 35. It’s compact size and permanently attached wrist strap allowed it to be an easy carry around camera on an all day trip to the zoo. The few times I needed to put it in my pocket, it easily fit into my cargo shorts with the lens collapsed.

The viewfinder is large and bright and it’s location in the upper left corner makes it perfect for left-eye shooters like me. The lack of a rangefinder means that nearly 100% of the light that enters the viewfinder goes to your eye. This is in contrast to cameras with a rangefinder where the light for the main part of the viewfinder has to pass through a beamsplitter which darkens the image a bit. Even if a rangefinder could be as bright as a scale focus camera like this, the lack of one was not at all an issue. For anyone whose never shot a scale focus camera, it is not hard at all. The depth of field afforded by the semi-wide angle 40mm lens makes everything but close-ups really easy. I’ve said this before in many other reviews, that in many cases, I find scale focus cameras to be faster and easier to shoot than rangefinder equivalents. While a rangefinder isn’t bad, it’s one of those things that when it’s there, you feel compelled to use it, even when you don’t need to.

My one and only criticism is that the side effect of such a compact design, the controls are a bit cramped. I recently complained (twice) about the controls on the Zeiss-Ikon Contessa 35, but for me, that is a completely different camera that has unnecessarily cramped controls. The Rollei’s serves a purpose, which is to make the camera as small as possible.

At this point in the review, it’s probably no surprise to tell you that I loved this camera. So much that in the time after shooting the two rolls of film in the gallery above, and publishing this review, I arranged a trade with another collector to have my very own Rollei 35. Mine has the Tessar lens, but is the earlier non-T Rollei 35. I can’t wait to take that one out and shoot it, and if I have any new and meaningful conclusions, I’ll be sure to come back here and update this review, but for now, I’ll award Anthony Rue a VIP Gold Star for correctly predicting how much I would love this camera!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rollei_35#Rollei_35_T

http://www.alexluyckx.com/blog/index.php/2019/12/06/camera-review-blog-no-113-rollei-35-t/

https://www.rolleiclub.com/cameras/35classic/info/35-T-Singapore.shtml

https://casualphotophile.com/2017/03/24/rollei-35-se-camera-review/

https://www.japancamerahunter.com/2014/09/rollei-35-review-david-aureden/

https://kosmofoto.com/2019/01/rollei-35s-review/

https://www.35mmc.com/25/11/2017/rollei-35-cameras-review/

https://www.anatomyfilms.com/rollei-35/

https://allmyfriendsarejpegs.com/2020/04/21/rollei-35s-camera-review/

Inherited my mother’s Rollei 35, shot several rolls of film with it, but could never get into it. Finally sold it several years ago. I found carrying it on its single strap a pain. I hated the fold-down pressure plate and found loading film to be difficult. I also felt the controls hard to work with. No doubt about quality, but not fun to work with. Others mileage may vary. Nice review. WES

What?! Someone doesn’t love the Rollei 35?! 🙂 Just kidding of course. This is definitely a camera that I could see is not for everyone. What one person sees as a charming quirk, someone else could see as an infuriating obstruction. I’ll admit to struggling a bit with loading as it’s something you definitely want to do with the camera sitting on a flat surface to do, but I didn’t really talk about this much in the review. The good thing about collecting cameras though, is that if one model doesn’t suit your fancy, there’s a million others to try!

In order to use the meter on cameras utilizing mercury batteries you can adjust the ISO setting to compensate for the higher reading.

You’re right, but the problem is that most people tend to use alkaline replacements to Mercury batteries, and alkaline has a very different discharge rate at which the voltage continually decreases throughout it’s entire life. The adjustment you make with the ASA/ISO speed dial would only be accurate with the battery at that charge. Once it ages, and loses some it’s charge, you’d need to keep changing it. Mercury maintained almost the exact same voltage from fresh to almost dead, so no adjustment was necessary. If you can find silver oxide replacements, those are more closely similar to mercury, but they’re hard to find.

You can use an MR9 adapter with a 357 silver oxide cell for exact voltage, or you can use an adapter without circuitry, or small washer, or O ring with the 357 and either adjust the ISO or have a repair person adjust the meter to use 1.5 volts directly. I agree about not using alkaline.

Good to know! There aren’t many cameras I would consider doing this for, but the Rollei 35 is one of them! Thanks for the info.

A sad memory! For many years, a T was always with me… wonderful thing it was too! But I lent it to a friend who forgot to refer to my note about the proper procedure for winding-on, retracting, and extracting the lens. So it came back to me wjth the lens permanently extended.

Not a big deal, I said… simply a fixed-lens unit now. But I soon discovered that the rewind release switch was also jammed in place. A little web research told me that it was beyond my ability to fix. So I sold it on the “bay” as a parts-repair unit.

The whole advance-before retracting thing IS a bit counter-intuitive. But I still wish my friend had remembered to read my note!

Excellent review Mike, as usual. I’ve had a 35 S in my collection for quite awhile and love it. It’s truly a keeper. I’ve tried before to get a friend of mine to get one but so far he’s resisted. I sent him the link to your review and now he’s sounding like he may go get one! Good job Mike!

Great review! I’d seen pictures and discussions of the Rollei 35, but it didn’t interest me – until I came across one at an estate sale. It is quite the little gem, and for 60$ in great shape I had to take it home. Really enjoyed using it on a cruise we took a year ago (just before everything shut down) and was very pleased with the results.

My favorite moment with it was when I took a picture some school kids happened to be in, and they ran up and asked me to show them their picture

My experience was similar, in that for one reason or another, I never had a strong desire to check one of these out. It wasn’t until I was sent this one to give it a chance, that I saw it’s appeal.

Mike,

I bought mine new in 1974 and have been using it off and on ever since…only 48 years Mine is the Singapore 40mm Schneider f3.5. I think the lens is amazing and I rarely miss focus. I had the meter adjusted for “new” batteries but sunny 16 doesn’t need a battery. Recently, after not using it for a while, I shot a roll and was delighted remembering how effortless it is to shoot…hyper focal all the way!

Thanks for the article.

Keep up the great work.

Patrick

Hi Mike. Just discovered this site.

I had a Rollei 35 many years ago, but then got sucked in to the convenience and undoubted quality of digital / iPhone photography…until recently getting the bug back for good old fashioned Analog photography, and more importantly the Rollei 35. I succumbed to a Rollei B35 that I saw for a reasonable sum on Ebay, and have now augmented that with a 35T; and am totally loving ‘relearning’ the fun and anticipation of using these brilliant cameras which make you ‘think’ a lot more about your shots than ‘point and shoot’ iPhone photography (which still has its place I think).