This is a Pigeon 35 Model J, made by Shinano Camera Company Ltd. in Japan, starting in 1954. The Pigeon 35 Model J is a slightly improved version of the earlier Pigeon 35 from 1952 with a better lens and shutter. All Pigeon cameras shared a similar feature set and other than lens and shutter combinations were essentially the same camera. Cameras like the the Pigeon family were popular in Japan as they were obvious attempts to suggest a German made camera, but at the economical price of a Japanese camera. Despite their rudimentary feature set, the Pigeon 35 is pretty well built and with the 3-element S-Lausar lens, is capable of pretty nice images.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 4.5cm f/3.5 Tomioka S-Lausar coated 3-elements

Focus: 0.75 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Scale Focus Direct View

Shutter: NKS Leaf

Speeds: B, 1/10 – 1/200 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Cold shoe with ASA Type Connector

Weight: 565 grams

Manual: None

How these ratings work |

The Shinano Pigeon 35 Model J was an economic choice for the mid 1950s Japanese photographer who wanted an easy to use and capable camera with German styling. The build quality of this camera is on par with other mid-tier Japanese cameras. The image quality from the 3-element Tomioka lens don’t come anywhere near that of quality German lenses, they do produce a vintage look with heavy vignetting which might appeal to someone looking for that aesthetic. I found the simplicity of the Pigeon appealing and enjoyed my time with it. if i were to buy another, I wouldn’t pay a lot of money for one, but wouldn’t turn down a deal either. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 30% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 10.4 | ||||||

History

When you look back at the best Japanese made 35mm cameras of the mid 20th century, you likely think of one of Nippon Kogaku’s excellent Nikon rangefinders or SLRs, or one of many Leica Thread Mount rangefinders produced by Canon, Nicca, Leotax, or several other smaller companies.

If there was an alternate reality where neither the Nikon rangefinder or any Japanese Leica copies were ever made, what 35mm models would the 1950s Japanese camera industry be remembered by? There’s a good chance it would be a camera with “Pigeon” in it’s name.

Prior to World War II, if you exclude Canon, nearly all Japanese cameras used either sheet film or paper backed roll film. When Oskar Barnack and Heinz Küppenbender both produced the first Leica and Contax cameras using double perforated 35mm “kine” film, other German manufacturers took notice. In 1934, the Eastman Kodak Corporation standardized how 35mm cinema film would be packaged and created type 135 film, which is the same type of 35mm film that is still available today.

In Japan however, 120 and 127 roll film cameras were all that could be found. Flipping thorough all the Group 3 cameras in Sugiyama’s Collector’s Guide to Japanese Cameras, there were very few 35mm cameras produced in the 1930s, and the ones that are there, are variations on the Leica rangefinder.

World War II slowed down the release of new models. After the war, both Japan’s economy and manufacturing ability was in disarray, further delaying new models. But in October 1948, a small company called Takachiho Optical Industries Co., Ltd would produce a compact 35mm camera with a fixed lens and leaf shutter called the Olympus 35.

Originally formed in 1919 as Takachiho Seisakusho, Takachiho’s earliest products were microscope and other optical products for scientific and medical use. In September 1936, the company would expand to photographic cameras, producing the first Olympus camera called the Semi Olympus, which was a close copy of the folding 4.5cm x 6cm Zeiss-Ikon Ikonta.

By the time the war ended, the demands of the photographic industry had dramatically shifted. No longer were folding roll film cameras in huge demand, so the release of the Olympus 35 was likely seen as a way to meet demand somewhere in between the high price of Canon and Nicca’s screw mount rangefinders, and an ever growing industry of cheap, entry level cameras. The camera was designed with two priorities, to be compact and easy to shoot. The rate at which the users would wind the film, cock, and fire the shutter, earned it the nickname the “pickpocket” camera as it’s speed was thought to be as fast as a thief could pick the pockets of it’s victim.

The Olympus 35 proved to be successful, allowing Takachiho Optical Industries Co., Ltd to rebrand itself as Olympus Optical Co., Ltd. to better align with the company’s goal of producing cameras. The Olympus 35 would be the start of a huge lineup of Olympus 35mm cameras that would remain in production throughout the rest of the 20th, and into the 21st century.

Around 1951, another company called Shinano Camera Company Ltd. would release a new camera called the Pigeon P which very closely resembled the Olympus 35. The Pigeon shared many of the same visual cues and control layout, but came with lesser lens and shutter combinations than the Olympus. The Pigeon 35 was most likely sold as a lower cost option for someone wanting the benefits of a compact 35mm camera but without the high price. Pigeon cameras were distributed in Japan by a distributor called Endō Kamera-ten.

The original Pigeon P was only produced for about a year before new versions of the camera with different cosmetics, but nearly identical feature sets were sold. According to Paul Sokk’s page on the Pigeon camera, Endō owned a trademark on the Pigeon name, and likely as a result, a large variety of Pigeon cameras were produced, sometimes under different names. One such Pigeon variant is the Lacon, which is claimed to have been made by the Lacon Camera Co., but according to Sugiyama, was in fact, made by Shinano.

One other Pigeon camera worth mentioning is the Pigeonflex TLR which was produced by Yashima Seiki Co., Ltd in 1953. Like the Pigeon 35, the Pigeonflex was also distributed by Endō Kamera-ten, which supports the claim that Endō owned a trademark on the name Pigeon.

The Pigeonflex was a pretty well built copy of the German Rolleicord TLR, and would later evolve into the Yashimaflex, and eventually Yashica branded TLRs. Around May 1954, it seems that Yashima ended their agreement to distribute TLRs through Endō. Pigeonflex cameras continued to be produced after this agreement with Yashima ended, but they were produced by someone else. Two other companies, the first called Alfa Optical Company, and second Towika Seiki also produced Pigeonflex cameras which are also very similar. Towiki produced Pigeonflex cameras were sold until at least 1956, well after Yashima had already established their completely unrelated Yashicaflex TLRs.

This relationship of Shinano’s Pigeonflex and how they evolved into the Yashica TLR is very confusing and has been incredibly well researched by Paul Sokk on his yashicatlr.com site. Paul has put an enormous amount of effort into explaining this history, so I won’t attempt to further simplify the story here, but if you are curious to know more, I strongly recommend you check out his site and keep reading.

Back to the Pigeon 35, the model reviewed here is the Shinano Pigeon 35 Model J which was offered as a lower cost version of the Pigeon 35 Model III. According to the Japanese language ad to the right, the Model J was offered for a price of ¥7,500 compared to an earlier ad for the Model III for ¥15,500.

I found no evidence that any of Shinano’s Pigeon cameras were sold outside of Japan, especially not in the United States. The possibility that the Pigeon name was a trademark of a single Japanese distributor, plus that it likely would have not made financial sense to attempt to sell these cameras out west almost certainly eliminated any interest in selling these in English speaking countries.

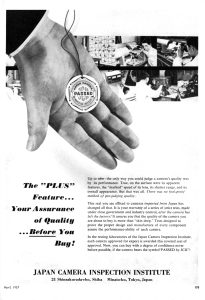

Shinano and it’s Pigeon cameras seem to have disappeared by 1955 which was likely a combination of increased competition from more and higher quality Japanese brands, but also the formation of the Japan Camera Industry Institute in June 1954.

The JCII was created by the Japanese government as a way to establish a set of guidelines and expectations that Japanese products were of high quality and wouldn’t diminish the reputation of Japanese made products. Companies like Shinano whose entire existence was to create cheap copies of other people’s cameras would have been primary targets of the JCII.

Today, Shinano, like most mid-tier Japanese camera makers from the 1950s seem to have disappeared into obscurity. While brands like Nikon and Canon both made historically important and highly desirable cameras, their cameras were still quite expensive and beyond the financial means of most people.

Cameras like the Pigeon were much more affordable and were likely the first Japanese cameras purchased by a much larger group of people. These cameras are generally not sought out by collectors, which is a shame as they represent a pretty important part in Japan’s photographic history.

My Thoughts

I don’t remember buying the Pigeon 35. Yet, there it sits on my shelf. Until recently, I could look at any camera in my collection and remember when I got it, where I got it from, and usually what I paid for it. Not this time.

I think it might have come from a large box of cameras Johnny Sisson sold me from Central Camera’s basement back in February 2019. In a way, I kind of like to think that’s how I got it because if so, then that means I likely saved it from destruction as Central Camera burned to the ground in early 2020. Had I not rescued it from that basement, it’s possible this camera would have perished along with so many others. Then again, I might have gotten it at a garage sale, I can’t honestly remember.

Regardless of how I got it, I got it, and one day last summer I decided to load in some film and take it for a ride. The Pigeon 35 Model J isn’t innovative, it doesn’t do anything that hundreds of other cameras do, it’s not especially well built, I mean, it’s not terrible, but pretty much everything about the camera screams, “meh”. I could probably stop right here, and know that I’ve likely written more about this particular model than anyone in the history of the Internet, maybe even ever.

The build quality of the Pigeon is both better than you’d expect from an unremarkable early 1950s camera from a company you’ve never heard of, yet still not to the level of many other Japanese cameras by Canon, Minolta, Asahi, or Minolta. At a weight of 565 grams, the camera has some heft, and feels sturdy in your hands, yet doesn’t have the reassurance of a German model. The only thing remarkable about the camera, is how unremarkable it is.

The top plate is pretty basic, which if you’ve ever handled a 1950s 35mm camera, has a pretty logical arrangement of controls. A film rewind knob is on the left, accessory shoe in the middle beneath an engraved Pigeon logo, followed by the externally threaded shutter release button, rewind release button, and combined film advance knob and exposure counter. The exposure counter must be manually reset after loading in a new roll of film and is additive, counting how many exposures have already been made.

The back of the camera is pretty bare, with only the round eyepiece for the viewfinder, and a large swath of body covering on the door. Embossed into the body covering are the words “Made in Japan” and a script Pigeon logo which at least hints at similar script logos on German cameras like the Kodak Retina.

Flip the camera over and there’s not a lot to see on the bottom. A large round lock in the center is used for opening and closing the camera. On each side are raised feet, which help balance the camera when sat on a flat surface. An interesting feature is that each of the two feet both have a 1/4″ tripod socket, giving you an option of which side to use. While this doesn’t give the camera balance like a center socket would, at least you get a choice. I cannot think of many other cameras with two tripod sockets on the bottom.

With the camera open, both the back and bottom come off in one piece, revealing a pretty ordinary film compartment. Film transports left to right onto a single slotted, fixed take up spool. The film pressure plate on the door is painted metal, and next to it is a small clip used to put pressure on the cassette as film transports through the camera. The entire film compartment is made of metal, giving a sense of quality, without any weight saving plastics anywhere to be found.

The inside of the bottom plate is covered in a black velvet-like material, but otherwise neither the door or any other surface of the film compartment has any sort of light seal material as the channels are deep enough to not require any.

Up front, all of the camera’s exposure controls are visible on the face of the NKS shutter. Shutter speeds from 10 to 200 plus Bulb are changed via a ring around the perimeter, and a small lever for selecting f/stops from 3.5 to 16 is on the left side. The camera uses front unit focus, in which the entire front lens elements rotate to control focus from 0.75 meters to infinity. Lastly, a flash sync port is near the 5 o’clock position around the lens.

The viewfinder is a straight through optical design. There are no frame lines or any other kind of information visible. Although small, I was able to see the entire rectangular image while wearing prescription glasses, so composing images was not much of an issue for me.

There’s not much else to say about the Pigeon. It’s design was meant to be simple and easy to understand for the novice photographer, a characteristic that I’d say they succeeded with. I’ve used many other, much more advanced cameras that were plagued by inconveniently located controls or quirky features that got in the way of it’s use. With a hand held meter, or a solid understanding of the Sunny 16 rule and a good ability to judge distance, not much else is needed to get good images from a camera like this, or is there?

My Results

For the first roll in a Pigeon camera in what likely was several decades, I chose a roll of film expired by at least two decades. Back in early 2020, I came across a large lot of heavily expired Kodak Gold 100 film. This film looked to be in good condition and I figured that since slow black and white films survive longer past their expiration dates, so would the 100 speed color film. I also figured the 100 speed film would be a good match for the Pigeon’s simple shutter. I loaded in a 36 exposure roll and kept it with me as a “walkaround” camera throughout the summer to see what kinds of images I could capture.

Depending on your expectations of expired color film, the results above are both bad and good. They’re bad in the sense that there is a very noticeable color shift, especially in the blues, but good in the sense the colors still have good contrast and sharpness, and for someone looking for an altered pastel palate, this film provides a very distinct look.

The film aside, I was impressed with the results from the simple Pigeon camera. The 3-element S-Lausar lens has good sharpness in the center with noticeable softness and vignetting in the corners. Dark corners can be seen in nearly every image in the gallery above showing that the lens struggles to cover a full 24×36 frame. For anyone looking for a distinct vintage look, the Pigeon would be an excellent choice for you.

Count me as a fan of the look these images provide, that combined with the altered colors of the expired Kodak Gold 100, the images above are some of my most interesting of recent cameras I’ve shot.

A few issues with the camera is that frame spacing was very uneven. The camera has a normal 35mm film transport that’s supposed to stop after 8 sprockets, but throughout the entire roll, frame spacing ranged from too wide, to overlapping on several frames. You can see it clearly in the pictures of the boat dashboard and the construction truck. Also, a few light leaks made their way onto the film, but neither of these issues are surprising considering we’re talking about an economy camera that is over 60 years old.

Beyond these minor conditional issues. I quite enjoyed my time with the Pigeon. The ergonomics are good, with all the controls in logical locations, exactly where you expect them to be. Although it would be an extreme stretch to suggest that this camera has anything to do with the Leica, a very loose similarity in styling likely benefitted it in this regard.

As collectors, I think we tend to group mid century Japanese cameras into one of two broad categories. On the high end, there’s the well known and highly regarded Nikon and Canon rangefinders, or those made by other companies like Nicca, Minolta, or Leotax. There’s also the legions of pretty really nice Rollei TLR copies by Yashica, Minolta, and Ricoh. But on the low end, there’s the billions of variants of the Hit style subminiature camera or a huge number of other Bolta film toy cameras.

People often forget about cameras like the Shinano Pigeon 35 Model J, an inexpensive and modest camera, that is much better than a toy, but doesn’t have the desirability of a Nikon SP. These were the cameras the average Japanese family would have bought to capture memories of their kids, vacations, and other important events. They were good enough for those cherished memories, but weren’t memorable enough to be desirable today. If you’re a fan of 1950s Japanese cameras, and want something a little different, you could do a lot worse than this.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Pigeon_35

http://www.yashicatlr.com/Pigeon35.html#modelj

https://yashicasailorboy.com/2016/08/01/pigeon-35-by-shinano/

https://www.photo.net/discuss/threads/shinano-pigeon-35-film-camera.460959/

Three years ago I bought one of these Pigeons from That Auction Site for maybe $15. The darn thing works fine didn’t even need a basic CLA. Not too shabby for an economy camera!

I purchased one a few months ago. It was part of a box of cameras 4 for $40. I only wanted one of the cameras and two of them worked fine.

The NKS shutter of the camera works, but the lens remains a tad bit open. I tried to clean it without dismantling the lens itself. The lens needs a CLA.

Let me ask, is this camera worth the expense of a CLA? The other option was to seach online for a functional unit and use this Pigeon camera as a backup. Thoughts?

I picked up this cameta at an antique store, heavily discounted because it want working. The shutter was stuck and the film advance was frozen solid as well. So for a small price I bought it. The shutter responded to a drop of lighter fluid in the shutter cocking lever slot. So that was easy. I was able to remove the top cover plate (lots of screws! ). I was able to lightly oil the brass gears and shafts (4 gears in total) and the film advance started working as well. I’d like to send you some of the photos of the operation if you’re interested.

Thanks for your cameta reviews!

Richard