This is the Nikon F2, a 35mm single lens reflex camera produced by Nippon Kogaku in Tokyo, Japan from 1971 to 1980. The Nikon F2 was the follow up to the very successful Nikon F. It was a high end and rugged camera aimed at professional photographers with a huge number of features that were sought after by the pros. It improved upon the original F with a wider variety of metered prisms, a hinged rear door, a faster 1/2000 shutter speed, a larger reflex mirror, better support for accessory motor drives, and several cosmetic improvements. The Nikon F2 only uses a battery for it’s meter, but is otherwise fully mechanical. While all Nikon F-series cameras were built to a high quality standard, the ruggedness and full mechanical control of the F2 make it highly sought after today.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

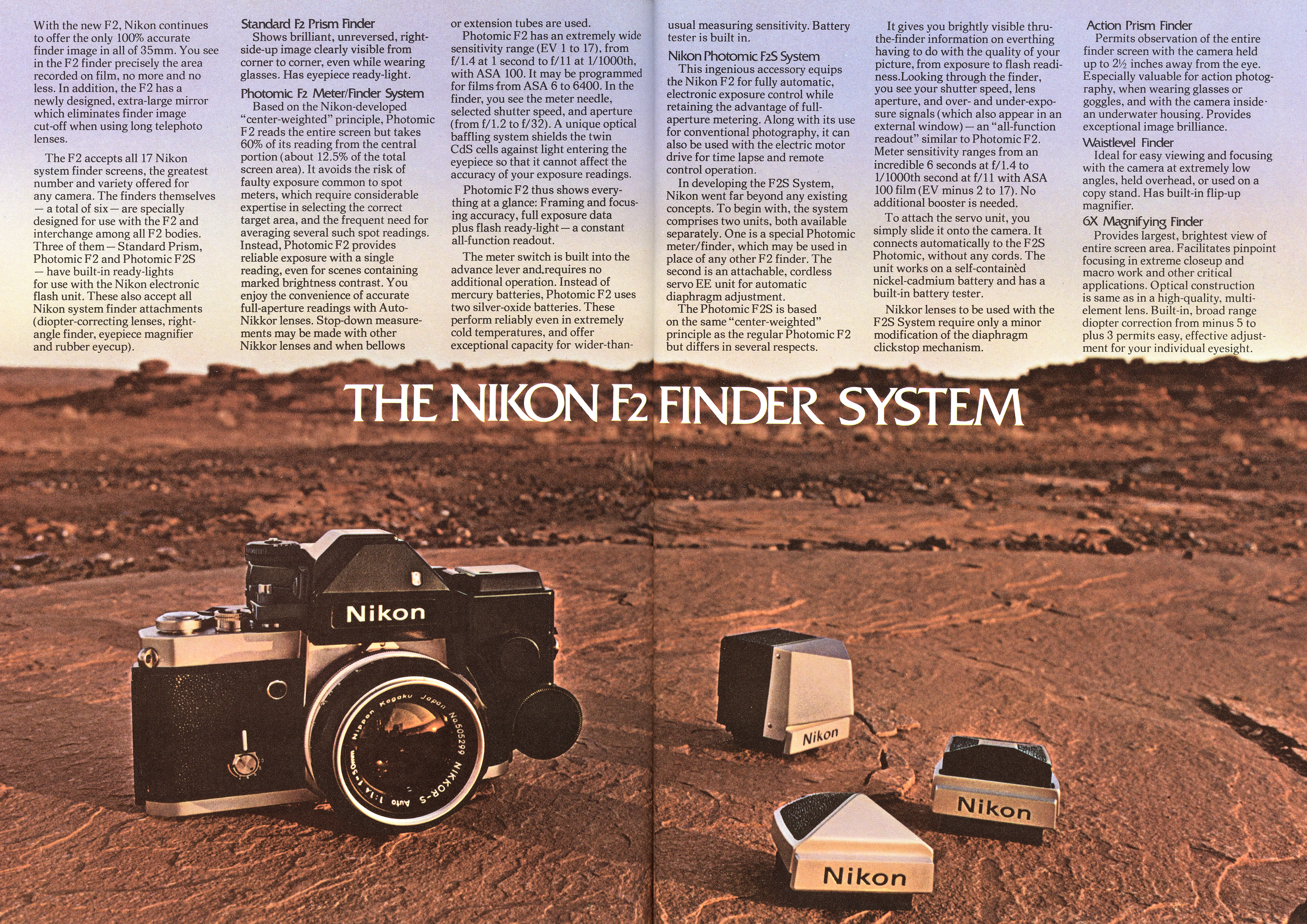

Lens: 50mm f/1.4 Nikkor-S.C Auto coated 7-elements in 6-groups

Lens Mount: Nikon F Bayonet

Focus: 1.5 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Interchangeable SLR Pentaprism

Shutter: Titanium Focal Plane

Speeds: T, B, 10 – 1/2000 seconds, 1/80 X-sync

Exposure Meter (DP-1 Photomic Viewfinder): Coupled CdS Cell w/ viewfinder match needle

Battery: (2x) 1.5v LR44 or SR44 Battery

Flash Mount: Accessory Electronic Flash Shoe

Weight: 1152 grams, 846 grams (w/ finder, no lens), 627 grams (body only)

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/nikon_pdf/nikon_f2_photomic.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Nikon F2 is a camera that needs no introduction. As the successor to the Nikon F, the most highly respected professional camera of it’s time, Nippon Kogaku wisely didn’t make significant changes to the camera it was replacing. Instead, the F2 is more like a refined F, with a hinged back, a more logical location for the meter’s battery, a higher top speed, and relocated shutter release. The F2 evolves the F into a more user friendly and easier to live with every day camera, one that is just as capable today as it was then. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 20% | |

| Bonus | +1 for it’s place as one of the most beloved, abused, durable, and rugged cameras ever made | ||||||

| Final Score | 14.2 | ||||||

History

When the Nikon F was first announced in March 1959, the photographic world was forever changed. The Nikon F (then called the Nikon Reflex) would raise the bar to a height for professional cameras that it would take decades for someone to even come close.

There were certainly 35mm SLRs before the Nikon F, there were professional 35mm SLRs before the Nikon F, and there were professional 35mm SLRs with most of the features that the Nikon F had. In fact, if you look at the list of features of the Nikon F, features like a three claw bayonet lens mount, pentaprism viewfinder, interchangeable viewfinder and focusing screen, motor drive coupling, instant return mirror, automatic diaphragm, and metal foil shutter, each of these features was available on a camera prior to the Nikon F.

If the Nikon F wasn’t a new type of camera, and it didn’t offer a lot of new and exciting never before seen features, why was it so successful?

Nippon Kogaku’s approach with all Nikon cameras and Nikkor lenses had two key priorities that other companies didn’t have. The first, was extreme quality control. Going back to the 1930s when Nippon Kogaku produced the lens mounts for the Hansa Canon, it was said that just as many were rejected than passed. Collectors of these cameras know that it is extremely rare to find two with sequential serial numbers because so many were scrapped before they ever left the factory.

During early Nikkor lens production, Nippon Kogaku was able to achieve near perfect glass by hand inspecting 100% of all lenses that rolled down the assembly line. Other companies hand inspected their lenses too, but no one was doing it to every single one of them, not even Zeiss.

In the first few years of production of the Nikon rangefinder, there didn’t yet exist the ability to make camera bodies and backs that could form a perfect light seal, so the light seal channels of each camera were hand carved and molded to perfectly fit each body. If you look at any early Nikon rangefinder, you’ll see that the camera body’s serial number is also engraved into the inside of the back, to indicate that back was perfectly matched to that body. Swap backs from one camera to another, and it won’t fit perfectly.

There are many other examples of the high levels of quality control that Nippon Kogaku employed, but the other reason for their success is how much value they put into the input of professional photographers. During the Korean War and throughout the 1950s, Nippon Kogaku worked very closely with LIFE Magazine photographers like David Douglas Duncan, Carl Mydans, and Horace Bristol, giving them equipment to use for free and listening to their feedback. As other reporters and professional photographers would visit Japan, Nippon Kogaku would arrange for a free cleaning and repair service for any photographer who needed their equipment worked on, even if it wasn’t a Nippon Kogaku product. A photographer who needed his camera cleaned could arrange for his stuff to be picked up at the hotel he was staying at, it would be taken back to the factory where it was serviced by a technician and returned to the hotel in the morning where the photographer would take his equipment. The only thing Nippon Kogaku gained from doing this was the ability to work closely with these photographers and listen to what they were saying.

With their commitment to extreme quality control and the feedback they valued from the pros, Nippon Kogaku was able to design a 35mm SLR system that both worked like the pros wanted and had the features they wanted. This was the critical mistake that Canon made when designing their first Canonflex SLR. Like Nippon Kogaku, Canon was also a respected Japanese camera and lens maker who had extremely high standards for quality control. Like Nippon Kogaku, Canon spend considerable time and effort designing their first 35mm SLR. Both companies even announced their new SLRs in the same month, yet Canon’s SLR flopped so badly, that in an effort to salvage the R&D costs for the new system, lower end versions with fixed viewfinders and less features were quickly pushed out the door, and within 3 years after the Canonflex’s release, Canon wouldn’t even attempt to compete with the Nikon F. It would take them 12 years when in 1971 they would release the Canon F-1 which was their next attempt at competing with Nippon Kogaku.

The reasons for the Canonflex’s failure weren’t that it was poorly made. In fact, the build quality of the Canonflex was just as good as the Nikon F. It wasn’t the optical quality of their lenses, and it wasn’t even that it didn’t have a compelling list of features. In fact, the Canonflex had a couple features that improved on the Nikon F like a hinged film door, and with the release of the Canonflex R2000 in 1960, a top 1/2000 shutter speed.

The Canonflex failed because it didn’t meet the needs of the pros. Compared to the Nikon F which had several lenses available in the Nikon F mount upon it’s release, the Canonflex only had two. In addition the choice of a bottom plate film advance lever which was thought to allow for faster shooting than a top lever, was still a lot slower than a proper motor mount which the Nikon had. Making matters worse, the location of the film advance lever interfered with the tripod socket, meaning that when the camera was mounted to a tripod, it was extremely difficult to advance the film at all.

At Photokina 1960, a year after it’s release, the Nikon F was the hottest camera there. Demand was through the roof and orders came pouring in. At Nippon Kogaku’s Ohi factory where both the F and the Nikon rangefinders were produced, they could not make them fast enough. So many people wanted to buy the Nikon F that US distributors like Joe Ehrenreich demanded that Nikon stop producing rangefinders so that they could get more SLRs out. Although Nippon Kogaku would not end rangefinder production overnight, it definitely led to a quicker demise for Nikon rangefinders. The Nikon SP would be the last all new rangefinder to be released, and only the models S3 and S4 which were scaled down versions of the SP would ever be released after.

In the 1960s, if you were a professional photographer and you wanted to shoot 35mm film, you used a Nikon F. It was the most popular camera to be used during the Vietnam war and other conflicts of the 60s. The camera had an uncanny ability to survive horrible shooting conditions, such as frozen winters and hot and humid jungles. It didn’t mind getting clanked around or dropped as photographers often had to crawl around battlefields avoiding detection.

For all of the great things you could say about the Nikon F, it was Nippon Kogaku’s first SLR, and over the course of the next decade, new technologies were coming out and the demands of professional photographers were starting to change.

Not wanting to change a winning formula, Nippon Kogaku took their time with what would eventually become the Nikon F’s replacement. Work began on the follow up to the Nikon F in September 1965. The new camera would continue with the same priorities as the original, extreme quality control and a dedication to the needs of the professional photographer.

Prototype T-10370-1 to the left looks a lot like the final F2, but wears a Nikkor-S 50mm f/1.4 lens with a serial number that suggests it might have been made around 1968-1969.

At a glance, the most obvious sign that this is not a production F2 is the earlier Nikon logo on the front of the pentaprism with the skinny typeface used on the original F. No production F2 viewfinder has a logo like this. I cover more details about this particular prototype in my article, The Rotoloni Report 5: More Nikon Prototypes.

According to Nikon’s History page, the first completed prototype, then called the Model A, was completed in July 1970, but it is not clear whether the image to the left is that same prototype, as I imagine that many were created.

It would take over a year from the announcement of the July 1970 prototype before the camera was officially revealed. Now called the Nikon F2, in September 1971, the camera was revealed to a selection of 3000 news media professionals in six cities, Osaka, Sapporo, Fukuoka, Sendai, Hiroshima and Nagoya. Later that month, from September 17 to 22, the camera was officially revealed at the Keio Department Store in Shinjuku, Tokyo. Over 260,000 people showed up to see the new camera in the 6 days of the fair.

Improving upon the Nikon F, the new camera had the following features:

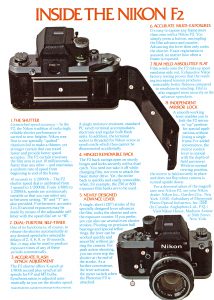

- Updated shutter with a top 1/2000 shutter speed and slow speeds down to 10 seconds using the self-timer

- Improved flash sync speed of 1/80 (up from 1/60)

- Hinged and removable film door

- A 2mm longer reflex mirror to accommodate a wider range of lenses

- Relocated battery compartment into the bottom plate, to allow for smaller metered prisms

- Reshaped body with rounded edges and relocated shutter release button for better ergonomics

- Improved Photomic finders with both meter readout and both shutter speed and aperture readouts visible

- Improved motor drives with speeds up to 5 frames per second and an automatic film rewind feature

- An optional DS-1 Aperture Control Attachment which gives the camera shutter priority automatic exposure

Perhaps the best feature of the Nikon F2 was that the camera largely stuck to the same formula as it’s predecessor. Build quality and quality control were still extremely high, the improved shutter retained the titanium curtains of the original, support for the full system of Nikon F lenses and viewing screens (but not viewfinders) was retained, as was support for depth of field preview, mirror lockup, and motor drive coupling. Basically, if the Nikon F could do it, the F2 could do it too.

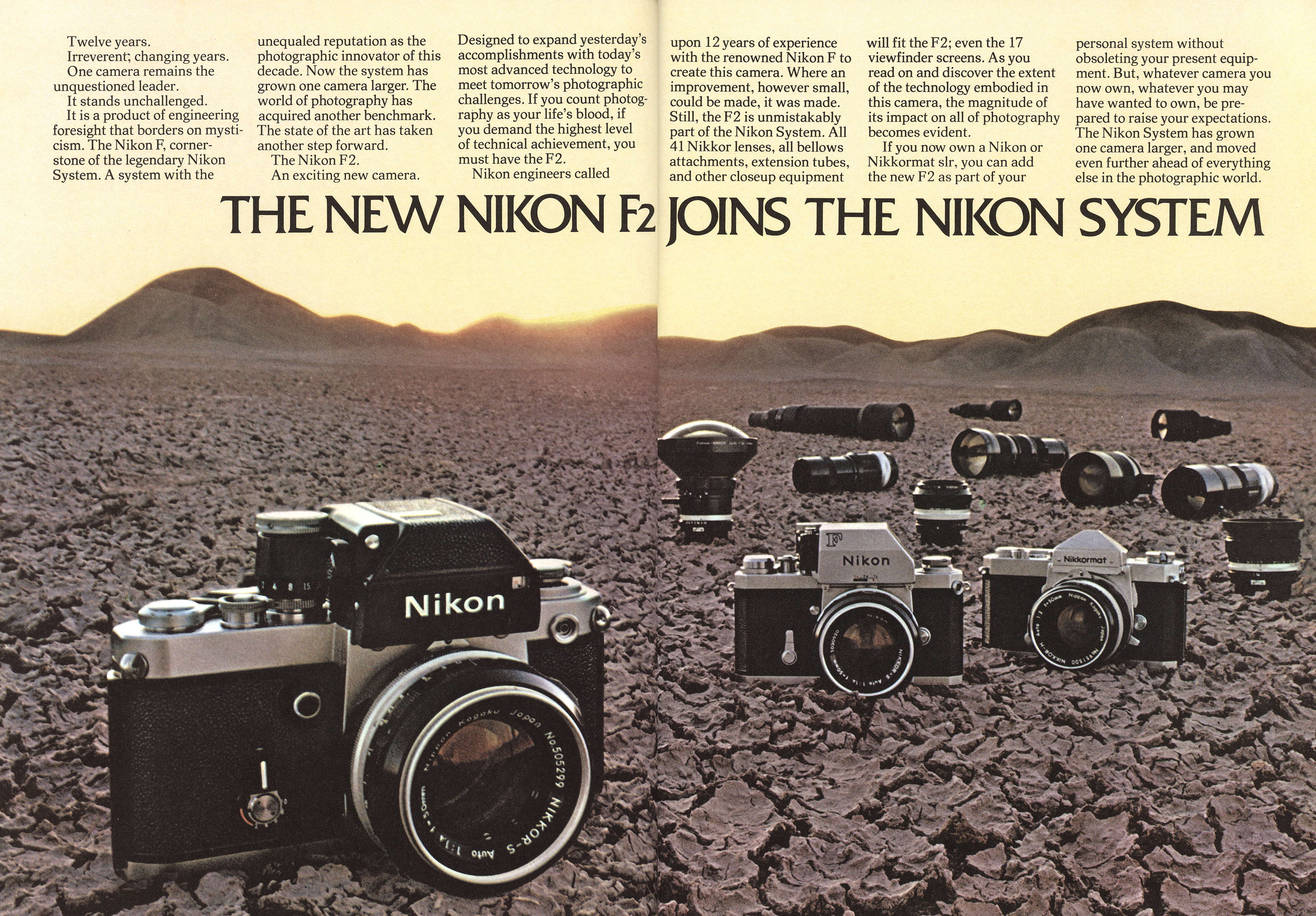

As was the case in 1959 when the Nikon F made it’s debut, Canon also had their competing model, the F-1. Unlike last time, Canon learned from their mistakes and released a camera that met the needs of the pros. The Canon F-1 was a very good camera that competed favorably to the Nikon F2 with the only exception being that photographers who already had a selection of Nikon F-mount lenses and a trust for the company who had been catering to their needs for the better part of two decades, very few photographers were willing to switch.

When it went on sale, the Nikon F2 was not cheap. Advertised prices for the F2 ranged from $330 for the standard prism and no lens, to $550 with the Photomic prism and Nikkor 50mm f/1.4 lens which when adjusted for inflation compare to $2125 to $3550 today. Although high, they were not out of line for what the Nikon F cost when it was new and with a more robust and established system that photographers could ease into, most had no problem opening their wallets to reserve one.

As you might imagine, the photographic press had a field day with the announcement of the F2. I wasn’t alive at the time, but I can imagine a pretty even split of nervousness for what might be different about Nikon’s new professional SLR combined with excitement for what would be new.

The two articles below the first written by Bob Nadler of Camera 35 and the second by Herbert Keppler of Modern Photography, both come from November 1971, right after the camera was announced and capture the excitement that people likely had back then. Both articles state the obvious that the Nikon F2 was more evolutionary than revolutionary. Changes to the shutter, body design, hinged door, prism, and the relocated battery compartment were mentioned in both articles as were a few nitpicks such as the sharp edges of the flash sync port, the small rewind knob, and the manner of which you externally couple the maximum aperture of the lens to the finder.

Reading through the two reviews, I can’t help but get a mild sense of disappointment that the Nikon F2 didn’t have one big “wow” feature that would have really gotten people’s blood pumping, but both Nadler and Keppler were smart enough to know that the F2 is exactly what pros needed, even if a few didn’t know it yet.

A great thing about a system camera like the Nikon F2 in which so many pieces are changeable, means that meaningful updates can be made to the camera without having to redesign the body. In addition to new lenses, including some with big advancements in zoom technology, one of the most significant upgrades to the F2 system came in 1977 with the release of the Photomic A and Photomic AS finders (also called the DP-11 and DP-12). Although these finders were backwards compatible with all F2s, when sold with them, the cameras were marketed as the Nikon F2A and F2AS. For existing owners of the Nikon F2, both the DP-11 and DP-12 finders could be purchased separately for $199.99 and $339.99 respectively.

The big change with both of these finders was support for new automatic indexing, or Ai, lenses. When attaching a lens to the camera, no longer did the photographer have to line up a pin with the rabbit ears on the outside of Nikkor lenses, and do a full twist of the aperture ring to calibrate the meter for the maximum aperture of the lens. This indexing was done automatically while the lens is being attached to the mount. Simply press the lens on the mount, give it a twist to lock it into position and you’re ready to go.

The Photomic A finder was the lesser of the two, using an analog match needle in the finder, and an older CdS meter with a sensitivity range of EV 1 – 17 using ASA 100 speed film. The F2A replaced the analog meter with a 5 segment LED display in the viewfinder, and a new Silicon Photo Diode meter with expanded sensitivity from EV -2 to 17.

The Nikon F2 would be produced for 9 years, just short of the original F, but that’s not necessarily a fault of the F2, rather it was the result of the onslaught of new technologies that would be created during it’s life span. Unlike the Nikon F which had little to no serious competition, the Canon F-1 was nipping at the F2’s feels and with other companies like Minolta and Asahi Pentax throwing their hat into the ring with their own professional 35mm SLR systems, Nippon Kogaku couldn’t wait as long as they did the first time around. Despite this competition, 862,600 Nikon F2s were produced, making them one of the most successful single camera models of all time.

The Nikon F2 was so popular, that upon Nikon’s announcement of it’s replacement the F3 in 1980, many photographers were concerned by the F3’s use of an electronic shutter and use of lighter weight plastics in it’s construction, that they continued to use their F2s well past it’s end of life. In fact, unsold and lightly used F2 inventory remained popular options in camera stores. If you were interested in trading in your F2 for a new and shiny F3, you wouldn’t likely have to try very hard to find someone willing to buy it off of you.

Today, the Nikon F2 is still an immensely popular camera, both for collectors and users alike. This was a camera that was built to the highest quality standard so that it could withstand anything anyone could throw at it. Wind, rain, heat, cold, bumps, scrapes, scratches, and even 40 to 50 years of time were no problem for the camera as many F2s can still be found in perfect working condition today, even if they show heavy signs of use.

That’s not to suggest that other Nikon F-series camera’s aren’t rugged too, but the usability improvements of the F2 over the original F make them a bit more desirable today, and for people who don’t have a need for too much automation, it’s fully mechanical operation is appreciated. 21st century film shooters like the F2 for many of the same reasons people liked it back then, it’s ruggedness, support for Nikon F-mount lenses, and it’s fully mechanical operation.

With demand though comes higher prices, and nice condition F2s, especially those with the DP-11 and DP-12 finders can fetch some serious dollars. Even in rough condition with a DP-1 finder, Nikon F2 bodies easy sell for between $100 and $200 on eBay. Add a lens, and the prices only go up, but that’s a small price to pay for a camera that’s not only a piece of history, but likely will keep working for decades to come.

My Thoughts

People often ask me how I got into reviewing and collecting old cameras. I’ve shared this story a number of times, so I won’t repeat too much of it here, but it started one day in 2014 when I was bored and on eBay. That first camera was a Nikon EL2 which I bought because I had heard I could use old Nikon film lenses on my Nikon D7000 I had at the time.

Fast forward nearly 7 years and now I’m writing about another 1970s Nikon SLR, the Nikon F2. This camera is actually a recent pick up for me, and one I didn’t spend a lot of effort trying to acquire as I already had a Nikon F and a bunch of Nikkormats, and I thought, how different could it really be?

When it comes to Nikon SLRs, there are people who love them and people who don’t. Of the people who love Nikon SLRs, almost everyone has their favorite, and I guess the EL2 has been mine. Sure, I have many others, even an F3 which I have yet to get around to reviewing, but the F2 definitely has a lot going for it.

My first impression of the F2 is likely the same impression most people have the first time they pick one up, which is “boy this thing is heavy”. With the Photomic viewfinder and 50mm f/1.4 Nikkor-S.C lens, the camera tips the scales at 1152 grams (2.54 lbs) which puts it well into TLR territory.

Another thing about this particular F2 is that some previous owner engraved his name, social security number, telephone number, and on the side of the prism, the words “Glenwood, ILL”. It was very common for photographers to engrave their names and other identifying marks on their cameras as it was thought this would deter theft. Professional photographers earned their living with their cameras, so they need a way to mark them as their own. Some collectors do not like seeing these engravings, but they do not bother me as I feel they’re “battle scars” from a life worth’s of use. To me, these are just as part of the camera as patina that most collector’s do like. As a very cool added bonus, I grew up in the town right next to Glenwood, Illinois, so knowing this camera likely spent most of it’s life within a few miles from me is extra cool.

Nippon Kogaku took an approach of not wanting to make significant changes to the successful formula of the original Nikon F, so from a distance the F2 doesn’t seem a whole lot different, but up close, there are some pretty big changes.

Starting with the left side of the top plate things don’t look too different as the F2 retains an almost identical popup rewind lever with folding handle and integrated flash hot shoe port. The F2’s rewind knob pops up to pull the fork out of the way when loading in a new 35mm cassette, which was a feature the original F did not require as the entire bottom of the camera was removed for loading film.

Next is the pentaprism, which attaches in the same way on both cameras, although original F prisms are not compatible with the F2. Each prism looks a little different, with the DP-1 here having a a visible match needle on top and the translucent window to let light in for the viewfinder.

On the right, there is a large dial, which with the metered prism attached, shows ASA film speeds on top and shutter speeds on the bottom. Some marks on the outer edge of the ASA film speed dial allow you to easily adjust exposure from -0.5 to +2 if you so desire. In the image below of the viewfinder removed from the camera, you can see shutter speeds marked on the top surface of the shutter speed dial. This is how it would look if you mounted the F2’s Standard Prism.. This is one of my least favorite designs of the DP-1 prism. Although the shutter speeds are easy enough to read from the side, I would have much preferred them to be on top, like on most 35mm cameras.

Next is the relocated shutter release button with an external collar that activates both the shutter’s Timed setting, and a shutter lock. Under normal operation, a dot around the collar should point forward, and not to either the T or L letter. Locking the shutter prevents it from being fired, and the Timed mode, allows you to leave the shutter open in Bulb mode without having to maintain pressure on the shutter release. The shutter release button itself is externally threaded to be used with a shutter cable or after market soft shutter releases.

To the right of the shutter release button is the automatic resetting exposure counter, which counts upwards from up 0 to 40 exposures for those of you who like to eek out an extra few exposures from your 36 exposure cassettes.

Finally, we have the plastic tipped film advance lever. Like the original F, the film advance lever has an approximate 15 degree standoff which both activates the meter and also allows for a shorter throw of the geared lever. From this stand off position, a full advance of the lever is about 160 degrees and can be completed in one single motion, or several shorter motions if you so choose.

On the bottom, the F2 has several differences, the first being the new location for the battery compartment. Although the F2 body has no need for a battery, this battery is what powers the various metered finders. By locating the battery chamber here, allows for more compact viewfinders to be designed. Another prominent difference is the visible location for the F2 motor drive coupling. The Nikon F has one too, but you must remove the bottom plate to access it. The switch to a hinged back and non removable bottom plate means that motor drives for the original F are not compatible with the F2. There’s still the same bottom lock for reloadable metal film cassettes, a 1/4″ tripod socket, and the new location for the rewind release button, which was changed from an A/R collar on the top of the original F.

The back of the camera has the same location for the viewfinder release to the left of the eyepiece. Despite being very similar in design, and attaching the same way, the viewfinders for the F and F2 are not compatible with each other. In the center of the door is a rectangular frame for the box end of your film to help remember what kind of film is loaded in the camera which was a feature that would disappear once manufacturers started adding the small peepholes in the door.

Removing the viewfinder is one of the more inelegant aspects of the F2. Press in a tiny metal button with the tip of your finger nail and lift up on the viewfinder. Except it is not that simple as you also need to press down on a lever on the front right side of the viewfinder to release two metal prongs holding the front of the viewfinder in place. Even after pressing both the lever and button, while simultaneously lifting up on the viewfinder, there’s a good chance the meter coupling pin (the bunny ears) will get hung up somehow. It is easier to do without a lens mounted, but to have to remove a lens before changing the viewfinder is a bit absurd.

With the viewfinder off, you can also change the focusing screen. To do this turn the camera upside down and with one hand covering the focusing screen, press the chrome viewfinder release button a second time and the screen will fall out into your hand. Remember when installing in a new screen, the dull side faces down.

I am certain that pros who regularly use the F2 will see my complaints as mere nitpicks, but at the very least, it is something a new user will need to familiarize themselves with as most every other company who offered an interchangeable viewfinder did it differently.

With the camera to your eye, the viewfinder is large and very bright. I have no scientific proof of this, but this is one of the brightest SLR viewfinders of any camera from the F2’s era. Brightness is even across the entire image, even in the corners. Although the two images showing in and out of focus views was taken outdoors, when looked at indoors, composing and focusing your image is very easy.

My example has the standard Type A focusing screen with a split image focus aide and 12 mm circle around it. Later F2s likely would have commonly come with a Type K screen which also adds a microprism collar around the split image. When it was released, a total of 13 different focusing screens were available.

With the DP-1 Photomic finder, you also get both a shutter speed and aperture read out in addition to the match needle scale. Each of these three items are illuminated by light entering the top of the prism, so if you are shooting in a dark area, these can be hard to read. Later prisms were available with LED readouts.

Up front, the Nikon F2 has one of it’s most important features, which is the Nikon F-mount shared by the earlier Nikon F. Although today, we have more than half a century’s worth of lenses to choose from in the F-mount, when it was released, the Nikon F2 was only the fourth camera to use this mount behind the original F, Nikkorex F, and Nikkormat so the ability for pros to keep using their existing lenses was a huge selling point of the F2.

Like the Nikon F, the camera body itself has no index coupling to determine the maximum aperture of the lens. This is all done using the various metered viewfinders available for the F2. With the original Photomic DP-1, 2, and 3 prisms, the Nikon F2 natively supported non-Ai lenses as long as they had the external coupling pin. In 1977, with the release of the DP-11 and DP-12 prisms, the F2 supported Nikon’s new automatic indexing, or Ai lenses. When the Nikon F2 was sold with either of these Ai prisms, it was marketed as the Nikon F2A and F2AS, although the only difference is in the prism, not the body.

Like all Nikon F-mount cameras, the lens release button is at the 3 o’clock position around the lens, and removing the lens requires a clockwise twist to remove. When attaching a lens to the body, or when attaching any of the non-Ai Photomic prisms, the lens must be manually indexed by rotating the aperture ring on the lens left and right to each extreme. This will cause the coupling pin inside of the prism to properly connect with the bunny ears on the lens. Using the Photomic DP-1 finder like I have here, the maximum aperture of whatever lens you have attached should show in a small window in the upper right corner of the front face of the prism.

Also on the front of the camera are a couple more controls. Starting at the top is a push button depth of field preview button. With a lens attached, pressing this button stops down the lens to whatever aperture value is selected on the lens to see depth of field. Around the circumference of this button is the mirror lock up switch. To activate it, press in on the switch towards the body and rotate it counter clockwise. When the handle points to approximately the 7 o’clock position, two white dots will line up and the mirror will remain raised until you move this back to it’s original position. A locked up mirror is useful for long exposures or astrophotography where the shake of the mirror moving can affect the picture, or when attaching certain lenses like Fisheye Nikkors which protrude too far into the mirror box. Although the original Nikon F also had a mirror lockup feature, it wasn’t as elegant to use as it could only be activated after firing the shutter. With the Nikon F2, the mirror can be raised and lowered any time you like.

Near the bottom is the self timer lever which is also used to activate slow shutter speeds from 2 to 10 seconds. For regular self-timer operation, with the shutter speed dial set to any speed and the shutter cocked, rotate the self-timer lever counterclockwise so that the black dot lines up with any of the numbers from 2 to 10. Beneath the resting position of the self-timer lever is a chrome button that when pressed, activates the self-timer countdown. Upon reaching the end, the shutter will fire.

To use the long shutter speed operation, set the shutter speed dial to B and rotate the collar around the shutter release button to the T position. Rotate the self-timer counterclockwise so that the black dot lines up with any of the numbers from 2 to 10. When you are ready to fire the shutter, press the normal shutter release button and the shutter will remain open for however many seconds you have selected. There is no way to use both the self-timer and a long shutter speed at the same time like on the Ihagee Exakta.

Using, the Nikon F2 isn’t hard. In fact, I would argue this fact is one of the best attributes of the camera because it can be as easy or as complicated as you need it to be. If you need a simple mechanical SLR, it can do that, but if you need a professional tool with extremely long shutter speeds, a mirror lockup, and connections for a motorized film transport, it can do that too. But no matter how complicated or easy a camera is to use, it’s gotta make good images, right? I think you know where I’m going with this…

My Results

I’ve shot many Nikon SLRs before, and although none are quite the same as the F2, I wanted to try something different with this one, so for my first roll, I mounted my monster Zoom-Nikkor 100-300mm f/5.6 lens. This lens is not period correct for the F2 as it was first released in 1984, but being an Ai-S lens, means it will both mount correctly and couple with the DP-1 meter as good as anything from the F2’s era.

Although this lens is very large and heavy, it is one of my all time favorite zoom lenses. This is the same lens I use while collimating lenses because I can mount it to easily to a DSLR or my Fuji digital mirrorless and the focal range of 100-300mm is very useful for confirming precise focus. When used photographically, it offers a macro mode allowing you to focus as closely as 2.3 feet and has excellent optics. I’ve pixel peeped with this lens digitally, and it performs as good, if not better than modern telephoto zooms I’ve tried. Perhaps one day I’ll write a proper review of this lens, but for now, I’ll show what it can do on film.

The first roll of film with the zoom lens was Fuji 200, but I would later shoot the F2 with some Kodak Vision3 500T using the Nikkor f/1.4 lens seen throughout this article. I frequently shoot Vision3 50D, which is one of my favorite color stocks, but had recently come across a large lot of Vision3 500T, so the Nikon F2 was my shot time using this film using the Nikkor 50mm f/1.4 lens pictured throughout this article.

Capturing fast moving objects with a 100-300mm zoom lens on film isn’t the easiest thing in the world to do, but to the F2’s credit, shooting fast motion with an excellent viewfinder wasn’t the hardest thing I ever did either. Sure, I missed focus on a few shots, but a surprising number of them turned out really nice. On digital, I could have just selected an absurdly high ISO setting and enabled continuous shooting and went in “spray and pray” mode hoping to capture the one perfect shot. With my setup and the Fuji 200 film, I was impressed to see more winners than losers.

I won’t comment much on the quality of the images as of course they’re good. Nikkor lenses are some of the best out there, and I’ve shot them enough on a large variety of cameras, I already knew what to expect. The Nikkor-SC 50mm f/1.4 and Vision3 500T produced some winners too, although many of them had a strong cyan tint from the film, which I didn’t care for. Images with lots of reds and oranges turned out nice, but any colors with an even remotely cool palette, went to the extreme. This is clearly a result of the film, and not the lens.

As for the camera itself, I’ll get to the point because I know you’re all wondering, “Is the Nikon F2 the best Nikon?”

I’ve been doing this long enough to know that answering that question is a trap, as there is no “best” of anything. The Nikon F2 was certainly an excellent option back when it first went on sale, and it remains an excellent option today. The things I liked the most about it were it’s rugged, do everything style and controls. This is a heavy camera that inspires confidence in way that a lighter camera might not. It’s fully mechanical shutter means that no matter how much the camera has been used, assuming it hasn’t been abused, you should have no problem finding examples in good working condition.

I loved the viewfinder, the layout of controls, the long list of features, and of course the selection of lenses. The Nikon F2 improves on the original F in a variety of ways. Switching to a hinged film door makes loading film a bit easier, the relocated shutter release is a slightly more natural location for my right index finger, the enhanced range of shutter speeds from 10 seconds to 2 second, plus 1/2000 means that I have a few more choices for exposure, and while I have no real need for a mirror lockup, the simpler design is much more intuitive for those would need it.

Compared to later Nikon SLRs, the F2 offers no in-body automatic exposure (not without a very rare accessory), and the shutter speeds aren’t electronically timed, so if you need to be able to shoot exactly perfect 1/288 or 1/905 second exposures, you’re going to have to “settle” for 1/250 and 1/1000 on the F2. Perhaps the biggest con is the camera’s weight, which to be fair, even though the F3 is more compact, the F4 through F6 got a bit bloated in size too, so I don’t even know if the large size of the F2 is a con within the professional F-series.

I REALLY like the F2. I love how it looks and it’s history, it has almost everything I want in a vintage SLR, with some improvements to the original F making it a more natural shooter than that model. A small part of me wishes I had the DP-12 meter for it’s support for Ai lenses and the more accurate SPD meter, but the DP-1 is still very good too. I had a lot of fun shooting the camera for this review, and since it is part of my permanent collection, is a camera I will definitely come back to again, but I would stop short of saying it is my favorite Nikon SLR.

I can conclude that the F2 is a historically significant camera that is absolutely deserving of the praise many people give it. If you don’t want a large and heavy SLR, there are other options out there but for those who want an excellent professional quality 35mm SLR, it doesn’t get much better than this!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nikon_F2

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Nikon_F2

http://www.mir.com.my/rb/photography/hardwares/classics/nikonf2/f2/index.htm

https://www.photothinking.com/2019-04-20-nikon-f2-ultimate-legend/

https://casualphotophile.com/2018/11/05/nikon-f2-camera-review-nikons-pro-slr-evolves/

http://www.alexluyckx.com/blog/index.php/2015/03/11/ccr-review-5-nikon-f2-photomic/

https://fstoppers.com/film/film-camera-end-all-film-cameras-long-term-review-nikon-f2-481837

https://www.kenrockwell.com/nikon/f2.htm

http://www.meanbearmedia.com/2020/01/nikon-f2-camera-review/

https://imaging.nikon.com/history/chronicle/history-f2/index.htm

Great article.

Since the pandemic, boredom started me buying old cameras on ebay. I started as a Canon shooter years ago. Within the last year I added the Fuji X-T3 and Fuji X100F.

However, I was always intrigued by Nikon’s, so I started picking up some film cameras and lenses, including The F3.

When I laid my hands on the F2, that was it. I love the feel, the construction, the dials, everything. It is my all time favorite. I cannot fully describe what it is that makes it stand out to me.

I’ve got 20 something cameras of all varieties and manufacturers (35mm, medium format, folding, digital, film, slrs, tlrs, rangefinders, etc.).

It’s still the F2 that sits the best in my hand.

Classic.

Thanks for sharing your story Jack! It’s always good to hear someone give these old classic cameras a try and end up falling in love for them. My favorite Nikon SLR is still the EL2 and while I’ll stand by that it is an excellent camera, I’ll also acknowledge that at least part of my love for it was that it was my first Nikon film SLR as well!

I’m not sure what your thoughts are on rangefinders, but one that I strongly recommend are either the Canon 7 or P. Both are a lot of fun to use, have excellent build quality, and make wonderful images!

Hello Jack,

Nice honest ode to the Nikon F2! I too have been bitten by the “Nikon” bug some years back and finally earlier this year achieved my ambition of collecting all the pro Nikon film cameras, from the F to the F6. The last camera to make it into my collection was, strangely, the original F! The first shall be last I guess…

I just want to make a note about interchangeability of screens and viewfinders. Although the in-body battery of the F2 precludes swapping powered meters between the F and F2, unpowered meters such as the eyelevel viewfinder and popup magnifying viewfinder are backwards and forwards compatible. Slightly easier for F2 to accept F finders than the other way around, as for the F you need to remove the Nikon face plate to fit F2 finders. There is a practical application for this, as the F2 works really well in full manual with b&w film if you can train your eye to “guestimate” exposure.. Eyelevel finders for the F2 are as expensive as just the body, but older F eyelevel finders can be found more cheaply, and streamline the camere and make it lighter than metered prisms.

As for the finder release button, you’re quite fight in stating that it’s a pain to use! A trick I have is to press down on the finder with one thumb while pressing the release with the other thumb, and the catch releases almost immediately. Takes a bit of practice but once learned is a sinch. Talking of finders, I think it’s one of the most endearing qualities of professional slr’s, the ability to mix and match as needed. The best Nikon release has to be on the F3 though, followed by the F4. The F5 release by contrast has to be the worst of the lot, as it’s the same button press as the F/F2, but as it slides backwards into the button you’re pressing, makes for a very slow viewfinder release! The F6 sadly forgoes the removable prism.. a more “modern” camera and one I like very much.. but there is no beating the F2’s fully mechanical beauty! Or those 10 second exposures..

Cheers

As usual, a well constructed informative article. I am a Pentax man by history and use, but must admit that when I used the F2 I was struck by the robust, uncompromising, high quality it projected. They were built to last and take heavy use. Even though I prefer to use my Pentax MX or KX for their ease of handling, the MX in particular looks relatively dainty compared to this hunk of machinery. The F2 must surely be one of the highest quality built cameras in history, and it along with my F have their well deserved space in my collection.

I do have the Canon P as well, and as you mention, these have a quality build.

Arnold, I have both an MX and K2 here in good working condition (the MX is cosmetically very worn though). Any advice on which one I should review first?

Mike, the K2 is a more complicated and heavier beast than the MX and I don’t use it as much. The MX is my personal favourite as it is completely manual. I would love your comments on either.

I recently sold my F2 to fund a new lens for my digital camera. I regret it of course, but I just wasn’t using it enough. The person who bought it handled it with such reverence that I was immediately pleased that he would be the new custodian. Such a beautiful camera.

I remember that story, Peggy. It definitely helps to know the next owner is going to really take care of and appreciate it! It’s only a matter of time though, before another F2 makes it your way! 🙂

I have a black one with DP-1 finder. I see yours has the bumps on the right from falling, just as does my father’s black Nikkormat FtN! What I like about the Nikkormat is the vertical shutter with 1/125 flash synchro. The F2 is a legacy camera but not as well balanced as the Nikkormat. I extra bought a motordrive to keep it from falling forward if you put on any big lenses. For example the Vivitar (Tokina all metal series) 35-105/3.5 is big and weighs 700 Grams…

Yeah, mine is heavily worn. Between the brassing, the engravings, and the various bumps and scratches, this camera definitely saw a lot of use, which is probably why it still works perfectly today. While I can certainly appreciate a mint condition camera that you’re afraid to take off the shelf, when it comes time to have a rugged SLR to go hiking with, I’d gladly take this F2.

As for the Nikkormat, I have several and you’re right, they’re great cameras. Things the Nikkormats can’t do like change the viewfinder is hardly a concern for me. As for the shutter, while yes, a 1/125 flash synchro is helpful with flash, I never use it.

Unless one needs the “system” interchangeability (which is probably very few film photographers these days), what gives the F2 any advantage over the Nikkormat EL? Styling and ergonomics were upgraded from the FT Nikkormats parallel to F, to the EL/F2 “rounded” styling, controls given more standard placement. And, the EL offers AE to boot – albeit not even at F3/FE sophistication, but it seems to work anyway. And a pristine EL can be bought for a fraction of the cost of a well-used F2.

For those who want an F2 for what it is, great. But thinking about cost-effective solutions to get into the Nikkor system (esp the less expensive but optically equal pre-AI lenses) with the “improved” solution, an EL seems to be a much better option.

I’ve written about both the Nikkormat EL and the Nikon EL2, even going as far as declaring the EL2 my favorite Nikon SLR, but in terms of reliability. In a post-apocalyptic world, the mechanical shutter of the F2 will far outlast the electronic one on both the ELs. If you need ultimate reliability, that’s the better choice. But as you pointed out, auto exposure and not needing a full camera system, the ELs may appeal to more people today.