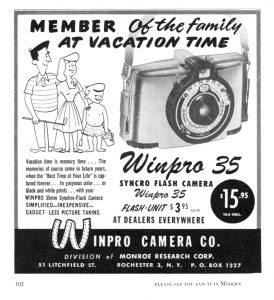

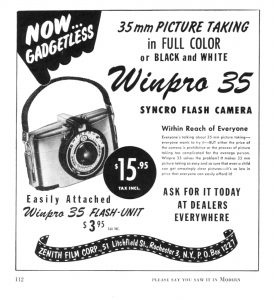

This is a Winpro 35, a 35mm point and shoot camera first made by Webster Industries and then later by Zenith Film Corp., both of Rochester, New York, USA between the years 1947 and 1955. The Winpro 35 is historically significant as it was the first camera to have a body made entirely of molded plastic. The type of plastic was called Tenite and it was first invented by Kodak in 1929. With an original price of $10.95, the Winpro 35 was very attractive to novice photographers and sold very well. Despite being a simple and easy to use camera, it had several innovative features such as it’s frame counter, and strap latches which doubled as locks for the film compartment.

This is a Winpro 35, a 35mm point and shoot camera first made by Webster Industries and then later by Zenith Film Corp., both of Rochester, New York, USA between the years 1947 and 1955. The Winpro 35 is historically significant as it was the first camera to have a body made entirely of molded plastic. The type of plastic was called Tenite and it was first invented by Kodak in 1929. With an original price of $10.95, the Winpro 35 was very attractive to novice photographers and sold very well. Despite being a simple and easy to use camera, it had several innovative features such as it’s frame counter, and strap latches which doubled as locks for the film compartment.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 40mm f/7 Crystar uncoated doublet in 2-groups

Focus: Fixed Focus, ~6 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Scale Focus Optical

Shutter: Spring Tensioned Rotary

Speeds: Single Speed, ~1/50

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Winpro Flash Gun

Weight: 228 grams

Manual: None

How these ratings work |

The Winpro 35 is somewhat of a forgotten gem of American cameras. Overshadowed by Kodak and Argus’s wide range of cameras, the Winpro 35 is a fascinating example of a simple American camera that punches above it’s weight. With a couple innovative features, a reliable shutter, and one of the best two-element lenses I’ve ever seen, images from the Winpro 35 have that perfect balance of sharpness, good looks, and a vintage aesthetic. If you encounter one of these cameras for sale, I guarantee you, they’re worth whatever the asking price is. Highly recommended! | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 30% | |

| Bonus | +1 for innovative features and overall excellence at it’s price point | ||||||

| Final Score | 12.7 | ||||||

History

In the aftermath of World War II, one of many casualties was an almost complete stoppage of all of Germany’s camera and optical industries. Cameras by Leitz, Zeiss, and Rollei that were once easy to get, were now impossible to find. Exports of photographic goods to countries like the United States were non existent, so the demand for domestically produced cameras caused an uptick in new companies willing to produce new cameras to satisfy demand.

Established companies like Kodak and ANSCO pushed out cameras like the Kodak Medalist, Signet 35, and the ANSCO Automatic Reflex. New companies like Clarus and Vokar appeared out of nowhere with new designs like the Clarus MS-35 and Vokar II who aimed to get a piece of the action.

On the high end, cameras like the Bell & Howell Foton sold for over $700, but on the opposite end of the spectrum came a small plastic camera called the Winpro 35, which was produced by a company called Webster Industries based out of Webster, New York.

The company was founded by local businessman and airline pilot, Claude Wright, who with his partner James Wilmot sought to invest in a new company building cameras.

Special Thanks: Whenever there is a camera like the Winpro 35 that isn’t very well known, there is often one or two sources that get published in a book or somewhere on the web, and due to a lack of other sources, gets cited over and over again. People like me who research into the history of cameras like these, have to make the decision of whether or not we should keep citing that same info, or try to find something new.

In the case of the Winpro, I reached out to Claude Wright Jr, who is the CEO of Wright Beverages and the son of the man who started the company that built the Winpro. Mr. Wright agreed to a phone interview where I could pick his brain and see if there was more to the story. A large amount of what follows is based on that conversation I had with him.

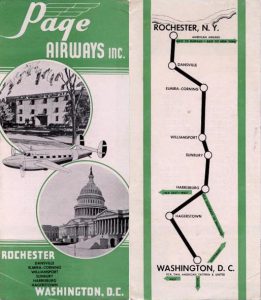

Wilmot had formed his own airline called Page Airways which in it’s early days was a pilot training school for the air force. Aspiring pilots would receive training by Wilmot and other instructors like Claude Wright, and after their training was complete, would move onto flight training school for the Air Force. Eventually, Page Airways would become a national distributor for Beechcraft airplanes in which Wright would often travel to the company’s headquarters and fly new planes back to the Rochester area where dealers would install sets and other avionics into the planes, paint them, and then offer them for sale to private companies. Both Wilmot and Wright would continue to operate Page Airways for the next several decades, with Wright finally retiring from the airline business in 1984.

In addition to their roles at Page Airways, Jim Wilmot and Claude Wright where entrepreneurs who invested their money in other Rochester area businesses. Shortly after the end of World War II, Jim Wilmot would become interested in buying an unfinished camera design from a Rochester area film company called Kryptar.

Kryptar was founded by an engineer named William J. Brown who originally worked for Taylor Instrument Company out of Rochester, New York. Brown was a highly skilled engineer and while working for Taylor, helped them design thermometers and other measuring devices. Brown had a passion for photography however, and would leave Taylor to start a new company called Technifinish who would build photofinishing equipment for other local businesses.

Technifinish saw moderate success in the 1940s and in 1946 would start to produce it’s own black and white photographic film which was sold at a price undercutting competing Kodak film. Along with their new line of photographic film, Brown hired a former Kodak engineer named Chester Crumrine to build a simple 35mm camera that he would sell alongside of his film.

In early 1947, Technifinish would rename itself to Kryptar and the sale of Kryptar film began. Realizing that the company was short on cash, William Brown abandoned the idea for producing his own camera and sold the design and all the rights for it to Jim Wilmot.

Together, Wilmot and Wright started Webster Industries in an old casket factory where the camera would be built. In my talk with Claude Wright Jr, he never knew exactly what attracted Jim Wilmot and his father to running a camera company, other than perhaps the fact that Rochester was also home to Kodak, one of the biggest camera and film companies in the country at the time, so perhaps that by coming up with an inexpensive camera to compete with Kodak, Webster could capitalize on all the talent in the area.

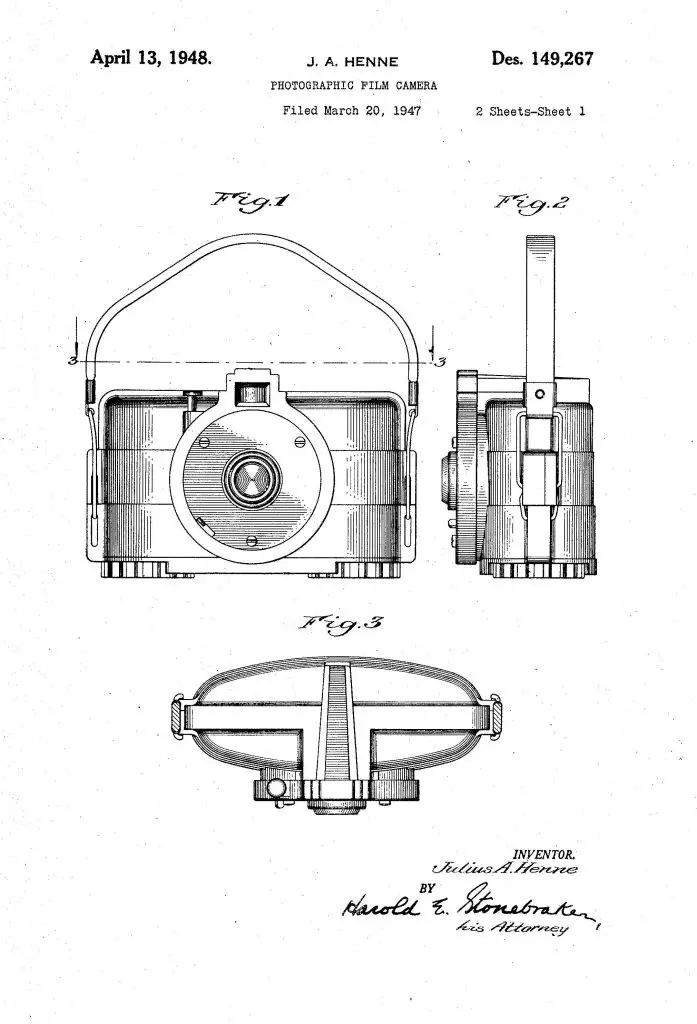

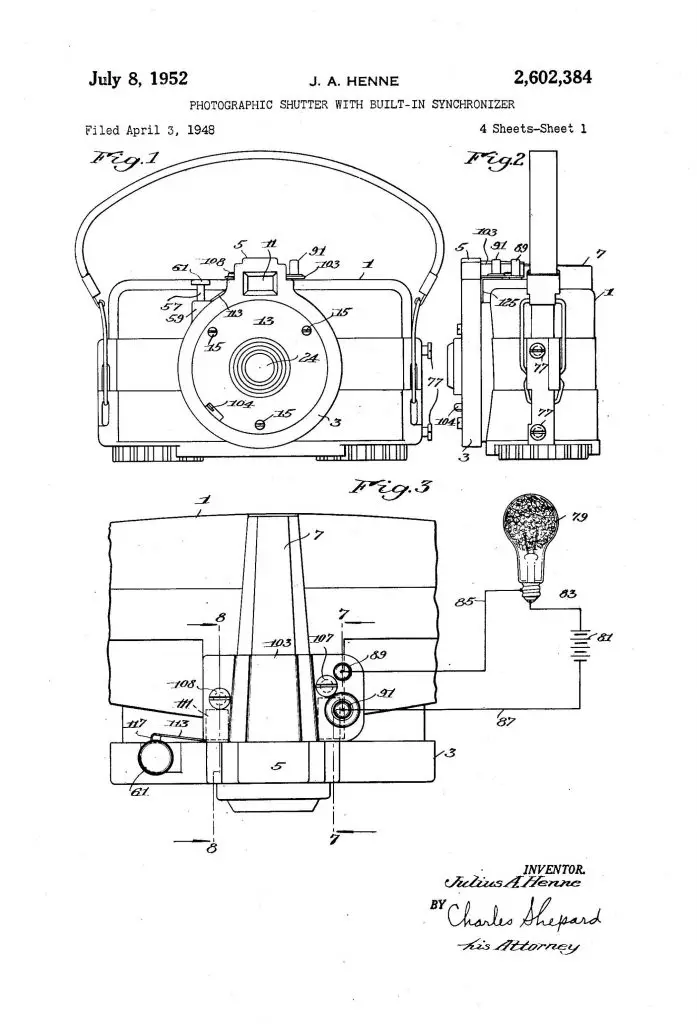

With only the plans for William Brown’s camera and no experience in how to make one, the men hired an independent camera designer and ex-Kodak engineer named Julius Henne to complete it for them. In the process of building the camera, Henne made significant changes. The shutter was completely re-designed using a flywheel governed shutter which allowed it to have very accurate timings, something not often found on other simple shutters. A glass doublet lens was created with a 40mm focal length and f/7 aperture which would allow it to have tremendous depth of field. Finally, a clever double hinge on each side of the camera served double duty as both strap lugs, but also locks for the film door.

Perhaps Henne’s most innovative contribution was a change in the material used to make the body. Unlike other simple cameras of the day who used brittle Bakelite or some variant of it, Henne leveraged his experience working for Kodak and chose a new type of injection molded plastic called Tenite. Tenite was produced by Eastman’s Chemical plant in Tennessee and was both stronger, lighter, and easier to mold. Shortly after the release of the camera, Webster Industries arranged a promotional stunt wherein Winpro cameras were reportedly thrown out of the window of a local business, and upon hitting the ground outside the building, survived the fall unscathed.

I asked Claude Wright Jr if perhaps Kodak had some stake in Webster Industries, perhaps helping them to make their new camera since Julius Henne not only used to work for Kodak, but also went back to work for them after the Winpro was completed, plus, the Winpro used Kodak’s own material to build the camera, and Wright wasn’t sure, only guessing that the entire Rochester area was so heavily dominated by Kodak and it’s employees, it was probably pretty easy to make arrangements between the companies.

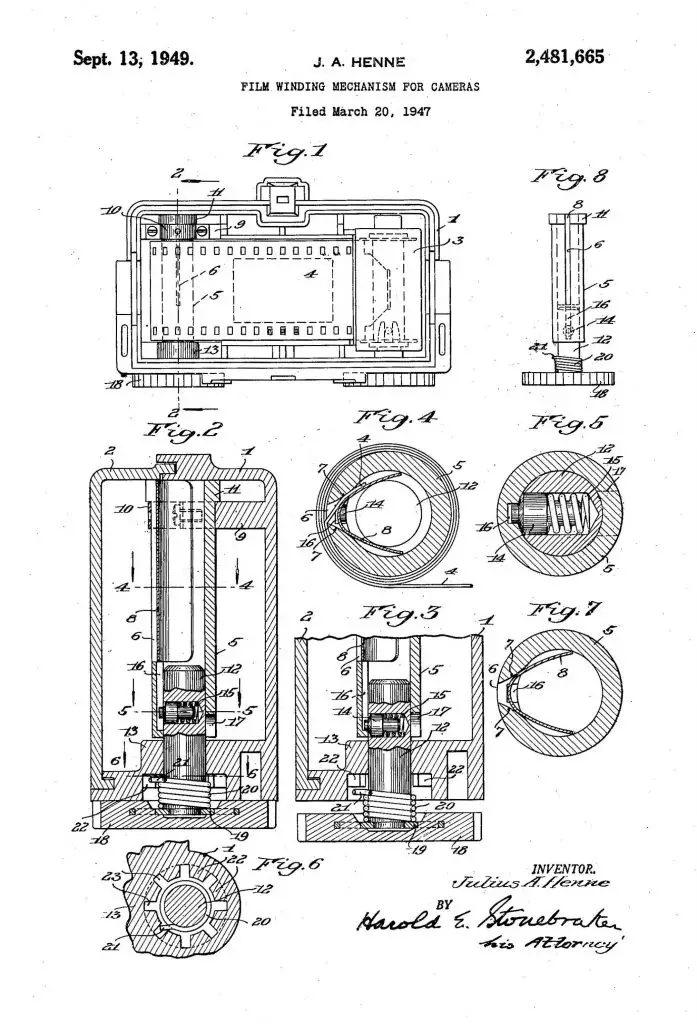

With all of Henne’s changes, little remained of the original Crumrine design other than the overall shape of the camera and a very unique film counter on the bottom of the camera which used a rotating disc with two holes in it. As the film is advanced, the disc would rotate to reveal the correct exposure number on a dial beneath.

When the camera first went on sale in November 1947, it had an advertised price of only $10.95, which when adjusted for inflation, compares to just $125 today, making the camera affordable to almost anyone who wanted one.

The Winpro was an immediate success, In the first two years it was available, over 150,000 units were sold. A year after it’s release, a revised version with flash synchronization was available and the price was raised to $12.

In 1949, Claude Wright and James Wilmot would sell Webster and the Winpro camera business to another investor in the Rochester area, and using the money from the sale of that company would partner with Jim Morrissey, a commercial broker who wanted to start a business building and selling prefabricated homes. With an infusion of cash from the sale of Webster, the three men, Wilmot, Morrissey, and Wright would start a new company called Wilmorite, a combination of the three men’s names. Wilmorite would later expand into commercial estate, investing in shopping malls and other businesses. The company still exists today.

As an aside, in my discussion with Claude Wright Jr, he clarified that Jim Morrissey had nothing to do with Webster or the Winpro. Resources online reference him as one of the partners that formed Webster, something he says would not have been true.

In 1953, Herb Pfieffer and Morris Cassorla of Rochester, New York based Monroe Warehouse Company, saw the potential for an inexpensive 35mm camera and thought it could be successful if marketed properly. They arranged to buy the dies and rights to the Winpro and would build and sell the camera under the name Monroe Research. The camera was mostly unchanged with one improvement which was an adjustable aperture allowing three different exposure settings. Within a couple of months of producing the camera, Monroe Research would rename itself to Zenith Film Corporation.

By 1953 color slide film like Kodachrome and Anscochrome was gaining tremendous popularity, but the film was expensive, and not affordable by someone interested in buying a $15 camera. In a strange twist of fate, Pfieffer and Cassorla partnered with none other than William Brown, formerly of Kryptar, who after a series of misfortunates and a warehouse fire, formed a new photographic film company that had a color slide film called Dynacolor which was created using expired Kodak patents.

Dynacolor did not compare favorably to either of Kodak or ANSCO’s modern slide films, but it didn’t have to, as it was much cheaper to buy and process, a perfect match for the target customer of the Winpro. Together with William Brown, who was reportedly excited about partnering with a company producing a camera that he was once involved with, the Winpro was distributed alongside Dynachrome, which was said to be it’s film of choice although any film would have worked.

Luck was not on Zenith’s side as continued distribution problems and a decline in quality control caused the camera’s sales to stagnate. Winpro cameras continued to be produced until 1955, at which time it was discontinued and the company closed up shop. Remaining stock of unsold Winpros continued to be available in Rochester area camera shops at closeout prices for $7.95 and less.

In my research for this article, I came across an interesting Winpro variant in the collection of Phil Sterritt which may be a prototype of a higher spec model, or simply a frankencamera put together by someone with a lot of free time. The camera to the right has a Wollensak Velostigmat f/4.5 lens on what looks to be a full focusing lens mount. This style of Wollensak lens is period correct to the Winpro and can be found in a number of other American cameras of the day, but the focusing mount looks to be professionally done. Whether this the work of someone with a lot of skill in making one off parts, or an official prototype for an future higher end Winpro is not clear, but is nevertheless interesting.

Today, cameras like the Winpro 35 are not often discussed in collector’s groups as it is a mostly forgotten model. Collectors usually don’t get too excited about inexpensive fixed focus plastic cameras, but unlike so many other cheap American cameras of the mid 20th century, the Winpro is unique in that did have some success, even if for only a couple years. It had a better than you’d expect lens, a couple innovative features, and with a production run of just under 7 years, it lasted longer than other “one and done” cameras like the Clarus MS-35 or the Univex Iris.

My Thoughts

I try not to think of myself as a film snob, and in the years since I’ve been reviewing cameras, that I’ve been just as far to expensive top of the line cameras as I have been basic plastic models. Of course the number of cameras made in the past century and a half is extremely vast, and I’ll never get to them all, so there are lines that sometimes I have to draw. People often ask me how I choose which models I write about, and the answer I always give is that I pick cameras that are interesting to me and ones that I think I’ll have something to say about.

When I first became aware of the Winpro 35, I chalked it up as another cheap mid 20th century camera with a single or double element lens which isn’t very interesting to use and probably delivers results on part with hundreds of other similar cameras made in every country back then.

It wasn’t until my friend Adam Paul picked up a Winpro somewhere and shared with me some images he got with his and I was amazed at how good they looked for such a cheap plastic camera. That led to a discussion where Adam proclaimed his love for this model and how fun it was to shoot that I came to the realization I needed one of my own.

It would take a while before one would come my way, as another criteria for which cameras I choose to review is that I need to find them cheaply. I was happy to get this later variant when the company was called Zenith Film Corp as I think the red and black face plate is more visually interesting than the other models, even if they largely work the same.

The Winpro is an attractive camera, but the first time you pick one up, and feel it’s 228 gram weight, any hope of a high performance camera will be met with a great deal of skepticism. As I played with the camera and discovered some of it’s clever features like the strap lugs which also double as the film door lock and the very clever exposure counter, it definitely grew on me.

In terms of it’s use, there isn’t much to the Winpro. The top plate contains none of the camera’s controls other than the shutter release button and in the case of flash synchronized models like this one, two metal posts for the camera’s proprietary flash.

Flip the camera over however, and things start to get interesting. At each end of the camera, the bottom is dominated by the large black Rewind and Wind knobs. Both knobs are clearly labeled with white paint filled engravings describing the function of both knobs, plus a large curved arrow indicating which way they turn. Unlike most 35mm cameras, the Winpro does not have a rewind release button or lever. When you reach the end of a roll of film, you simply pull up on the wind knob to disengage the film transport and then you can turn the Rewind knob, pulling the film back into the cassette. The large diameter of both knobs makes turning them quite easy.

The coolest thing on the bottom is the circular exposure counter in the middle. The counter is coupled to the sprocketed gear inside the film compartment, so you must either have film in the camera to see it work, or as an alternative, you can open the camera and turn the gear by hand.

The counter is actually quite simple, featuring an inner disc with white numbers from 1 to 36 painted on them, and an outer disc with two round holes in it. The two discs are separated by a metal plate with a single square hole showing one exposure number at a time. When film is advanced, the inner disc with the numbers slowly turns clockwise and the outer disc with the holes quickly turns counterclockwise. As each of the round holes in the outer disc crosses the square hole in the metal plate separating the two discs, you can see an exposure number from the inner disc. Keep advancing the film and the inner disc slowly moves and the outer disc rotates to show the exposure number with the other hole. This whole process repeats all the way through the duration of the roll of film. When loading in a new roll of film, resetting the counter must be done manually by turning the gear inside of the film compartment until it starts back for the first exposure.

If you are having a hard time with my explanation, here is a short video showing how it looks with a test roll of film in the camera.

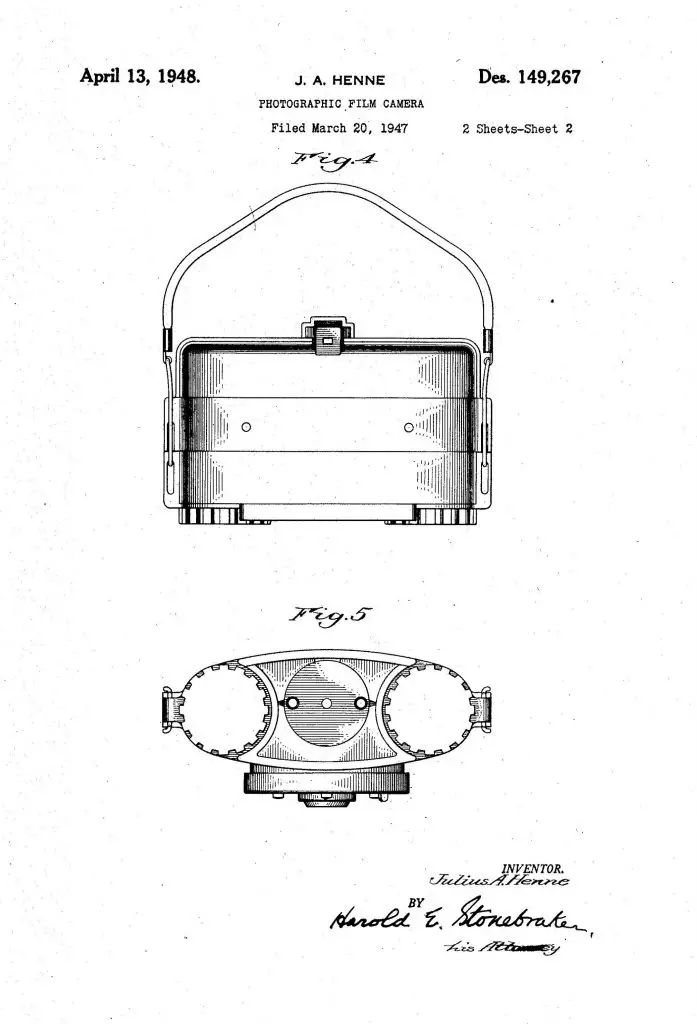

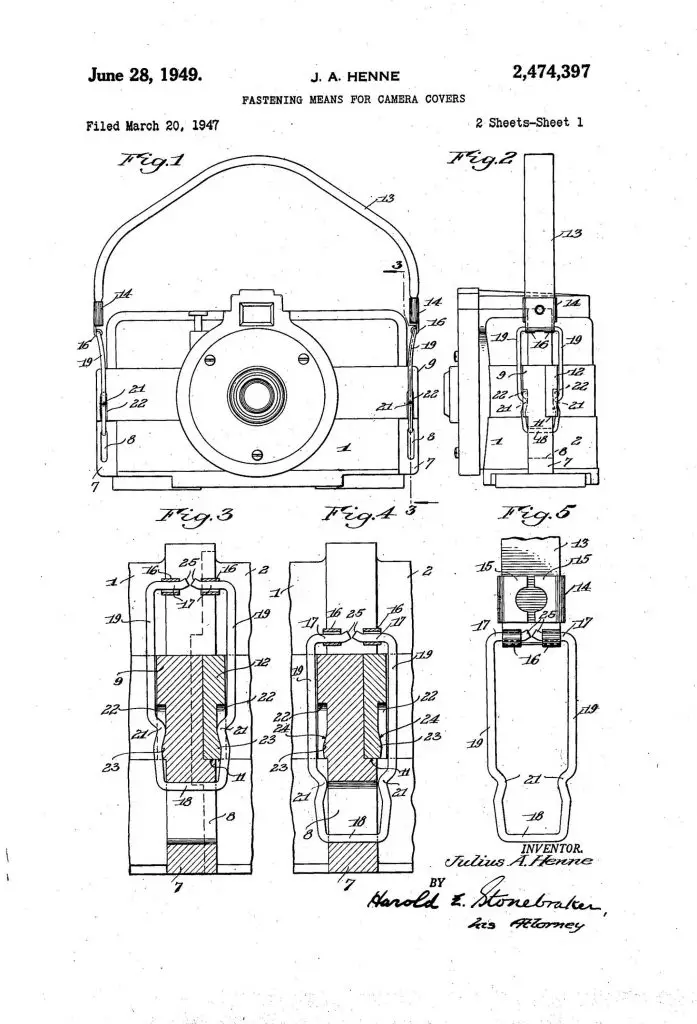

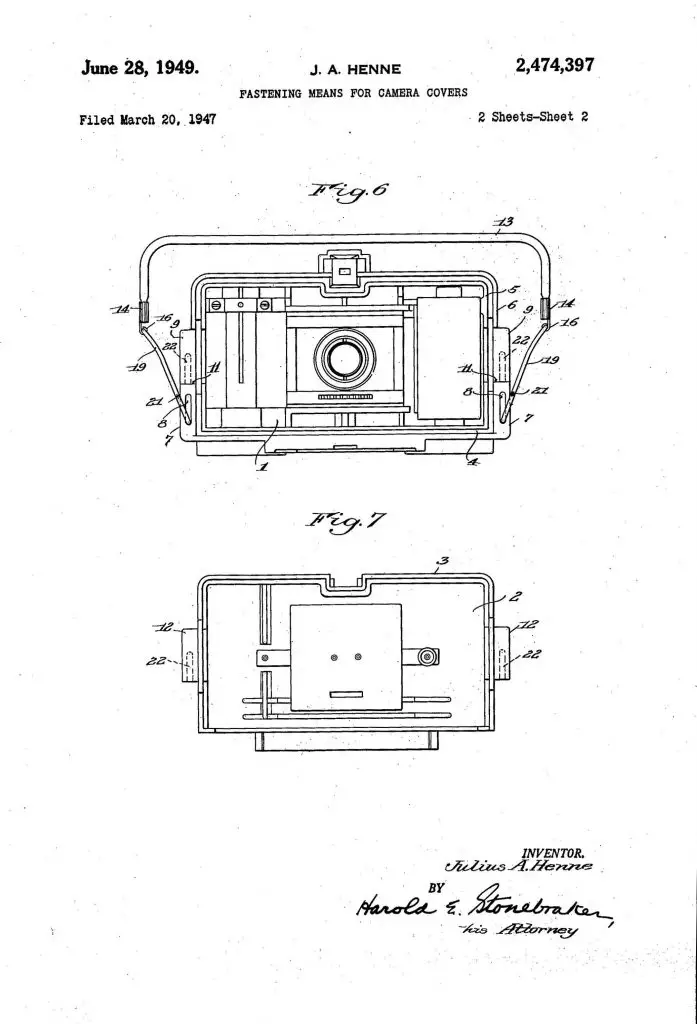

One of the Winpro’s other interesting design elements is in the wire strap holders, which also double as the door locks for the film compartment. When Julius Henne was designing the camera, this design for the strap holders was so unique, he was issued US Patent 2,474,397 ensuring that no one else could copy his design.

The wire strap holder is shaped in a way that can be slid up and down. When it is in the up position, it acts as a clamp holding the back of the camera to the front, making a light tight seal for the film compartment. When you want to open the camera, slide both strap holders down, and the clamp is released, allowing the entire back of the camera to come off. Contours in the plastic provide enough resistance so that it is unlikely that either of the strap holders could accidentally move.

With the back off, we see the Winpro’s simple film compartment. The film plane is curved, which was a tactic used in simple cameras to help minimize softness and vignetting near the edges of the image when using single meniscus or doublet lenses. The idea was that in a camera with a flat film plane, the distance from the rear lens element to the center of the film plane was shorter than to the edges. More sophisticated lenses can be constructed in a way that corrects this, but simpler lenses cannot, so by curving the film plane, an even distance can be maintained across the entire film plane from edge to edge.

With the camera oriented with the knobs at the bottom, film transport is from right to left onto a single slotted and fixed take up spool. Film loading is very easy as there isn’t much to get in the way. The distance from the supply cassette and take up spool to the film gate is very narrow, which means you should be able to get an extra exposure or two out of a roll since less film is wasted on the leader and tail of the film.

The back of the camera has very little to see other than the tiny opening for the camera’s optical viewfinder, plus a metal plate with exposure hints for the camera’s three Waterhouse stops riveted to the bottom of the door. Strangely, this plate is normally upside down with the viewfinder up. I guess it was assumed that a photographer would only need to read exposure hints while winding the camera.

Up front, the only means for controlling exposure is through the three Waterhouse Stops. Earlier Winpros did not have the three settings for small, medium, and large openings. This feature was added on cameras that were flash synchronized.

Although no f/stops are given, it can be assumed that 1 is wide open at f/7 with 2 and 3 allowing an additional stop of light for each, giving approximate f/stops of f/10 and f/15.

The Winpro’s shutter has only a single speed, which is estimated to be around 1/50, but a second slider has a Timed (actually Bulb) setting, allowing for long exposures although a lack of a tripod socket would make this more difficult unless a flat surface is handy.

The Winpro’s only other control is the shutter release which is comfortably located in easy reach of the photographer’s right index finger. The release is a simple metal plunger with no ability to attach a cable release.

Finally, the viewfinder is a simple straight through optical tube with glass elements at the front and back. The opening on the back is quite small, but with an approximate of the lens’s 40mm focal length, it is very easy to see your entire image, even while wearing prescription glasses. When I received this camera, the viewfinder was very dirty, but in the section below, I explain how to disassemble the camera to clean the shutter, but in doing so, you gain access to the inside of the viewfinder, allowing you to easily clean it.

The Winpro is both like, and unlike other inexpensive American cameras. It’s a largely hollow plastic box with a basic shutter and lens, and it sold very cheaply in the mid 20th century. But unlike the hordes of cheap Falcon, Imperial, and Hollywood cameras, the Winpro has a couple innovative features, and has a decent lens. How decent though, is what you likely really want to know. Keep reading…

Repairs

When I received the Winpro, it technically worked, but the shutter was sluggish, the aperture selector was stiff, and the viewfinder eyepiece was extremely cloudy. I figured this should be a pretty easy camera to take apart and clean, and I was right.

The Winpro 35 is without a doubt, the easiest camera I’ve ever taken apart. Disassembling the shutter is done by removing the three screws around the shutter plate…and that’s all.

With the screws removed, the entire shutter separates from the body, taking the front viewfinder glass with it, allowing you to get a Q-tip in there to clean the insides of both viewfinder lenses.

A metal flash sync linkage connects the flash ports to the shutter on models with this feature, but you can just take that part off and set it aside. The cosmetic shutter place lifts off, allowing you to separate the front half of the shutter from the rear. A rather thick c-pin allows you to separate the front lens element from the rear, allowing you to clean it.

Everything else is shown in the three images below. In the third image, I show you every single part of the camera, with the shutter entirely contained on the circular plate in the bottom right corner. I didn’t need to take the shutter apart and farther than this as a couple squirts of naphtha was all that was necessary to get it working smoothly again.

Putting it back together is just the opposite of taking it apart, and you’re done.

My Results

For the first roll through the Winpro, I went with my safe film, “freezer fresh” Fuji 200. This film I bought in mass quantities back in 2017 when Walmart stopped selling the 4-packs of Fuji 200 and 400. I still have a decent supply, but eventually it will be all gone, so I’ll have to come up with something else, but the thing that is great for using this film as a test, is that it’s entirely predictable. It’s not too contrasty or too vague, it’s not overly vivid, but also not pale. It’s got good latitude so it can handle a camera that maybe doesn’t have the most accurate shutter. Basically, you’re going to get predictable images from any camera you shoot it in.

After seeing the results from that first roll, I later shot a roll of bulk Rollei RPX25, a slow black and white film with a lot of contrast and very low grain. With these two different speed films, I would be putting the Winpro’s single speed shutter to the test.

Before shooting the Winpro, I was told to expect decent images from it, but when the first scans appeared on my monitor from my first roll, I was quite stunned at what I saw.

I was immediately impressed at the consistent sharpness across the whole frame from the simple, uncoated doublet. Contrast was a bit low in outdoor scenes as the uncoated optics simply cannot control errant light rays bouncing around in there, but they’re hardly bad. Although the Winpro’s lens has no threads for a lens hood to be screwed on, perhaps for a future roll, I will try to cobble together some type of makeshift hood to see if I can improve contrast.

The lens shows some barrel distortion as I noticed straight lines start to curve around the corners and vignetting is visible in some shots, but not much. Looking at the images of the dinosaur and bull statue, these were shot in bright sunlight using the smallest aperture, and only the slightest bits of softness are there in the corners. I am used to seeing blurred details and heavy vignetting on simple camera lenses, and the small amounts seen here are really impressive, suggesting the 40mm Crystar lens likely covers a circle much larger than the 24mm x 36mm frame.

One other problem which can be seen in the color playground picture, and both the church sign and water puddle black and white shots above is that one side of the image gets darker than the other. This is not a fault of the lens, rather the movable Waterhouse stops plate that restricts light through the lens. I noticed that on occasion, the “light hole” could get bumped and not be in the center of the lens, causing it to restrict more light on one side than the other. This could have been prevented had I paid closer attention to it’s position as I changed it, but is worth mentioning as it’s a simple mistake to make.

It might seem like I’ve come up with more cons to the Winpro than pluses, but everything I’ve mentioned above is something that comes with the territory with extremely basic cameras that retailed for around $10 when they were new.

What impresses me the most is how good everything else is. These images are way better than a $10 camera deserves to shoot, and with it’s simple controls and focus free operation, using the Winpro was extremely easy. As long as I kept at least 8-10 feet away from me and whatever I was pointing the camera at, I knew everything would be in focus. The three aperture settings worked well with the Fuji 200 film on a bright and sunlit day. I kept the camera on the smallest opening for most of the roll, only opening it up to 1 or 2 in heavy shade. When using the slower Rollei film, I kept the lens wide open for most shots, even in bright sunlight and I think the exposure came out great.

The Winpro 35 is a distinctly American camera from a little known American company. It’s story is as good as any out there, it looks great, is easy to use, and makes excellent pictures considering it’s low-tech design. I had been collecting cameras for quite a while before I ever heard of this little gem, but I am glad I did, and really hope that someone reading this decides to take a chance on one of these as I think you’ll be as impressed with it as I was.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Winpro

http://www.webstermuseum.org/winpro.php

https://rralexander.wordpress.com/2012/06/29/vintage-lomography-winpro-35/

http://www.collection-appareils.fr/x/html/camera-4112-Zenith%20Film%20Corp._Winpro%2035.html

Impressive results from this little camera!!

You need one Jim!

A funny coincidence, with perfect timing. I’m writing an issue of Monochrome Mania on 35mm toy and low-fi cameras. The WinPro 35 is the archetype of a cheap, low-fi 35mm camera. I haven’t shot with mine yet, but will soon.

Definitely shoot yours, you will not be disappointed! If you want to include a link to my review in your article, I could also link to yours once it’s live. Just email me the link or comment in here and I can add it to the main article.

An interesting, and if I may say, pretty little camera. With the two red lightning flashes I can’t get Captain America out of my mind for some reason!

I agree, I really like the red accents of these later models. Earlier Winpros had a cleaner, monochromatic face plate that’s kinda boring looking.

I got just one today.

Wollensak Velostigmat lens 2 inch f4.5