This is the Werra, a 35mm scale focus camera produced in Jena, East Germany by VEB Carl Zeiss Jena starting in 1954. This is the first version in a long line of Werra cameras that were produced in a variety of configurations until 1968. Later versions of the Werra came with selenium meters, rangefinders, and interchangeable lenses. The Werra has a minimalist design, locating most of the camera’s controls either around the shutter or to the bottom of the camera. One of the most distinct features of the Werra series is that the large lens cap also serves double duty as a hood. Although sold as a Zeiss product, the Werra is not made by Zeiss-Ikon as it was produced in Jena, a factory who predominantly produced lenses.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 50mm f/3.5 Novonar coated 3-elements in 2-groups

Focus: 0.9 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Scale Focus Optical Viewfinder

Shutter: Vebur Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/250 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Weight: 444 grams (w/ hood), 426 (w/o hood)

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/pdf_files/werra_1-4.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Carl Zeiss Werra is an interesting camera made in Jena, East Germany as it was not labeled as a Zeiss-Ikon like Dresden area Zeiss cameras were. It was designed from the ground up to be unlike any other camera ever made, and prioritize simplicity and sleekness in a minimalist sleek body. Later Werras would start to get more complex, somewhat negating the simplicity of these early models, but for the collector looking for a good looking but quirky camera that performs well, the Werra is an excellent choice. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 30% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 10.4 | ||||||

History

One of the more confusing names in collecting and writing about cameras is “Zeiss”. Although most known for their quality line of lenses, the brand Zeiss has been associated with a great deal of other products too. From cameras to turn signals, if it involved glass, there’s a good chance at some point in the 20th century, Zeiss likely had a hand in it.

Originally founded in 1846 by physicist and mathematician Carl Zeiss as Carl Zeiss Jena, it’s first products were microscopes and other scientific instruments. The name “Jena” refers to the town the company was founded in, Jena, Germany. In 1872, Carl Zeiss would hire physicist Ernst Abbe who would develop something called the Abbe Sine Condition which improved our understanding of how light passes through glass. It was this discovery that led to the creation of Zeiss’s finest lenses. Upon Carl Zeiss’ death in 1888, the company would change it’s name to Carl-Zeiss-Stiftung (Carl Zeiss Foundation in English) and the company would continue on as a leader in the photographic lens industry.

The early 20th century was a period of huge growth for the entire German camera industry with companies popping up with regularity all over the country. Many of these companies formed in or around the eastern city of Dresden due to it’s excellent transportation system. Dresden became the unofficial center of the photographic industry with over a dozen companies all competing in the camera and optics industries.

After the first world war, the German economy was in shambles and many of the medium to smaller companies found it difficult to stay in business. Many of them folded, but in 1926, by order of the German government, four different Dresden based camera makers would all merge together with an infusion of capital from the Carl Zeiss Foundation to form an all new company, known as Zeiss-Ikon. The four companies that would make up this new company were Contessa-Nettel AG, Erneman, Goerz, and ICA (who themselves were a previous merger of 4 different companies).

Located in Dresden, Zeiss-Ikon would combine the resources, experience, and current models of the 4 companies that it consisted of selling many of them under the Zeiss-Ikon name. As a unified company, Zeiss-Ikon would survive the poor Germany economy and would become a worldwide leader in the camera industry.

After World War II, Germany would be split into two halves, West and East Germany. Since Dresden was located in the eastern side of the country, it would fall under Soviet control. The town of Jena, Germany, where the Carl Zeiss Foundation’s headquarters was located, was incorporated into the Soviet Occupation Zone and would eventually become part of East Germany as well. As a result, many of the employees from the Jena factory fled to Zeiss locations in Oberkochen and Stuttgart, in Allied controlled West Germany.

From here, the histories of Carl Zeiss and Zeiss-Ikon get very confusing, and something I’ve written about before, so rather than repeat it here, the TL;DR version is that after a lawsuit between the East and West German versions of Zeiss-Ikon, the company was allowed to exist as two separate entities. In West Germany, Zeiss-Ikon would release an updated version of the Contax rangefinder, now called the Contax IIa and IIIa, and along with a former Zeiss employee named Hubert Nerwin, would put into production a wide variety of new models, including the Ikonta 35, Contina, and Contessa 35. Eventually, Zeiss-Ikon Stuttgart would release it’s first SLR, the leaf shutter Contaflex and after that, a focal plane shutter Contarex SLR.

In Dresden, East Germany, Zeiss-Ikon would evolve the Contax SLR and continue to produce various other former Dresden area camera models. In Jena, Carl Zeiss lenses would primarily be made. A huge number of Zeiss’s simpler designs like the Tessar were produced here for the M42 mount Praktica, KW Praktina, and a huge number of other eventual Pentacon brands.

Prior to the war, both Dresden and Jena had some of Zeiss’s brightest minds, but once the Soviet government took over, many of these workers were sent elsewhere, many to Kiev, Ukraine where entire assembly lines of the prewar Contax rangefinder were transferred to be built as the Kiev rangefinder. Many of these skilled workers were sent to train less experienced workers in building cameras and lenses, but after a few years, their services were no longer needed, so many found their way back to Jena where they originally worked.

With more workers than work, in 1953 by the order of the Ministry of Mechanical Engineering, Carl Zeiss Jena was given an order to create an all new amateur camera that reportedly could be sold for less than 100 Mark. The man most widely recognized as the father of the Werra was Rudolph “Rumü” Müller, an avid sports photographer, Müller had more of an engineering background than a design, but had wanted to build a people’s camera with a clean and easy to use interface. He discussed his ideas with Paul Oswald who was in charge of manufacturing in Jena and the foundations for what would become the Werra were born.

To keep the cost of the camera low, it would come with a simple 3-element Novonar, or for a little more, a 4-element Tessar. The shutter would be a central leaf without any ability for interchangeable lenses. The camera would not have a light meter or a rangefinder, but these features would be added later.

The choice of a green body covering is thought to have been chosen by Rudolph Müller who picked green to honor the lush green fields and landscapes of the state of Thuringia where Jena is located. According to the Spring 2013 Zeiss Historica newsletter, this explanation is doubted, but is the best one I’ve come across, but at the very least it seems it was a decision made by Müller.

In addition to being easy to use, Müller implemented several aspects of the camera’s design that were quite innovative, such as the metal (later vulcanite covered) ring around the outer collar of the shutter that acts both as the film transport and shutter cocking ring. The camera’s included lens cap could be reversed and used as a lens hood, and all non essential controls for the camera were located to the bottom, to keep the top appearance as clean as possible.

A prototype Werra seen above bears a strong resemblance to the finished model with the differences being a smaller viewfinder with circular eyepiece in the back, some extra screws and rivets in the metal, a large opening on the side of the shutter for the flash sync port, and a prototype VEB Optik Saalfeld Novitar lens.

When it was time to build the camera, a plant in the small city of Eisfeld on the river Werra was chosen, and is also where the camera got it’s name. When it was finished, the Werra made it’s debut at the 1954 Leipzig Spring Fair. The camera reviewed in this article is a very early variant with the chrome film advance ring. A year after it’s release, this ring was replaced by a green vulcanite covered version, but otherwise was the same.

The Werra was successful enough to warrant a variety of new models with improved features. In 1958, three new models called the Werra II, III, and IV were released adding a bright frame viewfinder and selenium exposure meter in the II, a coupled rangefinder and interchangeable lenses, but no meter in the III, and a new meter with coupled shutter speeds and f/stops in the IV. What started out as a simple camera with a minimalist appearance and feature set, was now an advanced and capable system camera, on par with the Kodak Retina IIIC.

As the years went on, further advancements to the Werra were made adding more features, even a prototype SLR called the Werraflex was developed but never released. To build a working SLR in the body of a Werra required an all new leaf shutter purpose designed for this camera, a compact pentaprism, and an all new lens mount. By the time the prototype was completed, management changes decided it did not make financial sense to build the SLR, competing with other SLRs being made in Dresden.

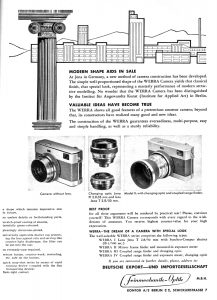

Werras were exported all over the world including the United States, although it does not appear to have been done in great numbers here. I could not find any US ads for the original model, but the ad to the right from July 1959 suggests that distribution of the first four models was being marketed to potential distributors. Although no prices are shown in the ad, in a May 1963 ad for the Exakta Camera Company, the Werramatic had a list price of $79.95.

The Werra series enjoyed a long life, being produced until 1968 with a huge number of variants in that time. According to an unofficial list of models, as many as 30 different Werras were made making having one of every Werra a tall task to undertake.

Although it is fascinating to see how the Werra evolved from such a simple camera to the advanced versions that came later, the additions of all those additional features worked against the beauty and simplicity of the earlier model.

Gone were the clean lines of the top plate and simple shutter and lens, and now there were external meters, additional windows for bright frames and viewfinders, more complex auto exposure systems, larger and more complex interchangeable lens mounts, and different combinations of cosmetics. I found no evidence of this, but I wonder what Rudolph Müller’s thoughts were on those later models which shared so little in common with his original version.

Today, the Werra is a very popular camera for collectors as it has a lot of things going for it. For starters, it’s history in Jena is different from other post war East German Zeiss cameras, it has a distinct look unlike any other camera ever made, plus with such a huge number of different variations, it appeals to the collector who likes to have complete collections of multiple models. Finally, for those who intend to shoot them, they’re quite good cameras, even the simpler ones. I don’t how many people would go through the effort to acquire one of every Werra ever made, but I feel confident in saying at least a couple of these belong on every collector’s shelf.

My Thoughts

The Werra is an interesting camera whose minimalist design gives it an almost decorative appearance, like it’s something that was created to sit on a shelf, rather than to be a photographic tool.

Of course, many people did use the Werra for it’s intended purpose, but upon handling one, it seems very likely that a good number of people bought this camera for it’s looks, rather than it’s operation. It was this emphasis on looks over operation that kept the camera off my radar for quite some time. That changed when I was talking to fellow collector Anthony Rue and he noticed that I had never reviewed a Werra and decided I needed to. A couple days later, a brown package showed up on my porch and inside was this green beauty.

Perhaps the camera’s most clever feature is the protected lens cover which also doubles as a hood. Unscrew the conical cover over the shutter and lens, separately unscrew the flat front piece, then reverse the cone part, and screw it back onto the lens and voila, you have a hood! Just make sure if you aren’t using the hood, you keep it safe as a great number of used Werras are out there without this part missing!

Up top there is the cable threaded shutter release….and nothing else. I don’t recall ever seeing a camera with such a barren top plate, not even a logo! The softly curved edges of the body are comfortable to hold allowing your right index finger to naturally fall where the large, domed, and chromed shutter release is.

It’s been my experience that whenever you have a camera with a minimal top plate, it just means the controls you’d normally find there are somewhere else, and on the Werra, it’s the bottom plate.

From left to right is the pop up rewind knob, 1/4″ tripod socket with knurled collar which doubles as the film back release, rewind release button, and exposure counter. On this earlier Werra, the rewind knob lacks a fold out lever, which was added to most later models. Although many cameras lacked a fold out lever, it’s omission on this model is a big deal as I found that rewinding the film after my first roll required quite a bit of effort, which with a lever would have made it much easier. Opening the film back requires you rotate the knurled ring until the back and bottom are free from the rest of the camera. Finally, the exposure counter is additive, showing how many exposures are made, and must be manually reset after each new roll of film is loaded.

The back of the camera, like the top plate is completely barren of all features, save for the rectangular opening for the viewfinder. From this angle, you can also get a good look at the leather wrist strap that came with this Werra. Unlike other original straps that are often found on old cameras, this one was still in very good condition and I felt confident supporting the weight of the camera using it.

With the film compartment opened, the camera takes on a strange appearance as the entire bottom of the camera is missing. Film transport is from right to left onto a single slotted and fixed take up spool. Inserting a new cassette and threaded the leader is quite easy, due to the openness of the design. Compared to a couple other German cameras with a removable back and bottom like the Rollei 35 and Altissa Altix where the film pressure plate folds down with the body, the pressure plate on the Werra remains with the back, meaning you don’t have to worry about folding it out of the way.

A curious design element of the film compartment is the bare metal film rails have these diagonal lines in them throughout their entire length. I am unsure of the purpose of these as it seems the extra texture would increase resistance on the film as it passes over it.

Edit 8/17/2021: Shortly after posting this review, Reddit user u/dokimus/ replied saying that the diagonal lines were designed to “stretch” the film across the film plane, helping to maintain flatness.

Removing the lens cover/hood reveals the rest of the camera’s controls, including focus, shutter speed, aperture control, and perhaps most interesting, the film advance control.

Closest to the body is a metal ring which on this model is deeply textured, later Werras replace the metal wheel with a flat, vulcanite covered ring. With film in the camera a twist of this ring both advances the film to the next exposure, but also cocks the shutter.

In front of the film advance, is a ring for setting shutter speeds. This ring is most easily turned via two small posts on opposite sides of the shutter, which when gripped by your fingers and twisted, selects speeds from 1 second to 1/250, plus Bulb. Focus is controlled by the middle ring, and finally aperture f/stops are selected via the front ring. With the hood attached, I found it was very easy to accidentally change the aperture, so this is something you’ll want to pay close attention to while out shooting.

From the camera’s right side, we get a look at the flash sync port, which while doing research for this review, I noticed is sometimes on the front of the camera, suggesting that different variations of the original Werra changed the location of this port. We also get a look at the thickness of the camera, which considering it’s short height, is rather long front to back. Although the Werra has some nice curves, suggesting a pocketable camera, it likely would not fit into a small pocket or purse.

The viewfinder on the early Werras are very simple optical viewfinders. There are no frame lines, focus aides, or anything else indicating the status of the shutter’s settings. It’s just a straight through piece of glass. Although not as large as later optical viewfinders like those found on later cameras like the Voigtländer Vitomatic, the viewfinder is large enough to where I had no trouble seeing the entire image, even while wearing prescription glasses.

The Werra is an interesting camera. Not only does it have a sleek look, unlike that of any other camera ever made, but it has a completely bizarre layout of controls. Despite the unorthodox locations however, the camera never becomes difficult to use. With a small amount of practice, you quickly get used to, and possibly even begin to appreciate it’s oddness. I applaud the creativity of the men and women in Jena who accepted to challenge to design a completely new camera from the ground up! Of course, a cool looking camera isn’t much of a camera if it doesn’t make good images.

My Results

For the first roll through the Werra, I loaded in some fresh Fuji 400 that I had in my freezer. It was late fall, the leaves had all fallen off the trees, and good lighting wasn’t always a guarantee, so I thought the faster 400 speed film would work well with the camera. I kept the Werra with me as I went about my daily business, using it like a point a shoot camera, similar to how someone who bought this new likely would have.

Before Anthony sent me this Werra, he told me two things. The first was that the lens was quite good and punches way above it’s weight, and to be careful when rewinding the film.

It turns out he was right on both accounts. The simple f/3.5 Novonar triplet does not have the reputation of many other quality Zeiss lenses like the Planar or Tessar but looking at the images it’s capable of, you’d be hard pressed to see a significant improvement in small prints made from negatives shot through the Werra. Softness and vignetting in the corners is evident, but it’s not distracting. Looking at the images at full resolution on my 27″ computer monitor, they’re not as razor sharp in the center as more well regarded lenses, but they’re hardly bad. For the amateur photographer who valued a sleek looking and easy to use camera over a more complicated one with higher end lenses, the Werra was definitely good enough for it’s target customer.

As for Anthony’s second warning, the lack of a fold out handle on this early model, means you have to grip the thin rim of the rewind knob and turn it by hand throughout the roll. On this particular camera, there was a lot of resistance in the film transport and it became clear that after a few turns, I would going to do more damage to my skin if I rewound the whole roll this way. I made a quick decision to just wait until I could get the camera into a dark bathroom so I could open it up and rewind the film outside of the camera.

The Werra is an attractive camera that despite it’s odd control layout is generally pleasant to use. Although the viewfinder wasn’t large, it was big enough to see the entire image while wearing glasses. The domed shutter release on the otherwise barren top plate was in a comfortable location for my right index finger. This particular example was a bit stiff in the film transport, changing shutter settings, and focusing, but I won’t fault a half century old camera that likely hasn’t been serviced in decades.

Even if I had the benefit of a 100% perfectly working and serviced camera, I couldn’t help but shake a sense of ambivalence towards using the Werra. Sure, I don’t have any major complaints, but there wasn’t enough about the camera that made me want to shoot more than a single roll through it. I think the emphasis on design makes it difficult for my mind to see it as more than just a display piece. Sure, it made great images, but so do well over a hundred other cameras in my collection.

Reviewing cameras is a challenge because there are so many different options, many of which compare equally to another, that it can sometimes be difficult to quantify my preference for one over another. I liked the Werra, I definitely see the appeal in collecting them, but as a shooter, it’s not for me.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Werra

https://casualphotophile.com/2019/01/16/werra-camera-review/

https://filmphotographyproject.com/content/reviews/2014/08/werra-film-camera/

https://krg.pagesperso-orange.fr/werra/werra.htm

https://oldcamera.blog/2019/11/06/carl-zeiss-werra-mat/

http://www.cjs-classic-cameras.co.uk/zeiss/werra.html

http://cameras.alfredklomp.com/werramatic/

https://www.rangefinderforum.com/forums/showthread.php?t=138794

https://www.photo.net/discuss/threads/the-wonderful-werra.481550/

I agree the Werra is a quirky piece. Once I got one, I had to have others. My favorite is a Green IV with the flat top and built in meter. The Synchro-Compur shutter is B-500 and does have the availability of using the interchangeable 35/2.8 Flektogon and the 100/4 Cardinar.

I find it is a great compact kit with both accessory lenses, and is certainly one of the most unique looking cameras, and have often been queried as to “What kind of camera is that?”, of course all in Olive Green!

Mike, if you limit yourself to just these earliest of Werras you will be missing the advances made with succeeding iterations. What may come as a surprise is with those kitted out with a coupled rangefinder, whether you go for the r/f only, or with the meter. Probably the best bet is to go with what is termed the “e” types, with the striated body covering, simply because they’re the last to be manufactured, although most of the earlier models are just as good if in decent working order.

No issues with de-silvering mirrors, dim images, and “losing” the rangefinder spot, they’re like slightly smaller versions of the split prism versions found in Leica M and Contax rangefinder camera, bright and contrasty. Faster shutter, up to 1/750, and interchangeable lenses, only three in total, but covering a decent 35-100mm range.

My three models, 1e, 3 (3rd version) and Werramatic e, all come from the last production series and I found them a delight when I was using them.

If it’s OK with you, here’s an excellent French site (open in chrome for a translation) giving an incredible amount of info about the range, making it a valuable reference for all Werra models. https://krg.pagesperso-orange.fr/werra/werra.htm

Note that the “Werra 1st” is a typo, this is the 1e.

I will admit that although I didn’t love this particular Werra, I have not soured to the entire series. I would love to try one of the other models someday, especially the 3 and Werramatic as you mention, but it’s a matter of coming across them. I sometimes buy cameras on eBay if I can find them cheap enough, but Werras don’t seem to cross my path often. I’ll definitely keep a look out for more models though.

My Werra came with a 51mm x 39mm card packed inside. The card has this text in German:

“Achtung!

Beim Aufschrauben der Sonnenblende als schutzkappe, darf die am Objektiv eingestellte Ectfernung 6 m bis infinity betragen. Kuerzere Entfernungen nicht zulaessig. Filter nur auf Gewinde des Schutzdeckels auf schrauben nicht zwuischen Objektev und Schutzekappe,

Schuetzen sie, wann Sie keinen Film eingelegt haben, die neuartige Film-buehne und diefeinstgeschliffene Andruckplatte vor Beschaedigungen! Legen Sie diese Karte zwischen beide Flaechen, damit sie sicj nicht beruehren!”

Translation by Google translate:

“Notice!

When screwing on the sun visor as a protective cap, the

distance set on the lens may be 6 m to Infinity. Shorter distances

are not permitted. Only screw the filter on the thread of the

protective cover, not between the objective and the protective

cap.

When you have not inserted a film, protect the new film stage

and the finely ground pressure plate from damage! Place this

card between the two surfaces so that they do not touch!”

I think a piece of business card or stiff bond paper would work as well.

My Werra is a “Werra I”, with a serial number 6526278 on the lens, which I think might mean that it was made in 1965. It appears to have been made for the export market. The focusing scale is in feet and meters; the shutter is a “Prestor RVS” with the VEB Pentacon tower logo; the lens is marked with the “Q1” symbol used on export products and says “Jena” instead of Carl Zeiss Jena and “T” instead of Tessar. I’ve got a roll of Kodak Ultramax in it right now. It’s the first roll I’ve put in the camera and I’m looking forward to seeing how the pictures turn out.

That is really interesting to hear how that card was used. It does make some sense though as the serrated edges of the film rail are definitely sharp and I could see them snagging on the pressure plate if misused. That said, I doubt many of those cards have survived so I am sure that it didn’t turn out to be the issue that the manufacturer anticipated.

Also, Mike, at some stage Werra dropped the flat-style traditional pressure plate used on the camera you tested, although they continued with the serrated film guides right to the end, but I have no idea which was their first model to use the new-style dimpled version. “Dimple” is probably the wrong word to describe the new version. The plate has a series of regularly spaced small nodules and it is the tips of these that come into contact with the film and significantly reduces the possibility of the guides damaging the pressure plate. I never had any issues with scratched films or film flatness, but quite why they went with the odd film film guide I’ve never seen an explanation.

It is clear to me that I definitely need to get more Werras so I can experience all these different versions! I will make a renewed effort to find a few more types. 🙂

Hi Mike,

as I am somehow adicted to the WERRAs I do have more than 50 variations of it in my collection – starting with some rare models like the SuperMat, an oringial brown leathered one or a half-cut model, also some WERRA 0 and Saalfeld-optics, silver ones etc.

So, what are you looking for? A good overview for at least the most common versions of the WERRA is provided in the book “WERRA – das Sammlerbuch”, published by Hartmut Thiele – written in German. And we supplemented this in different articles in our camera collectors membership magazin “Photographica Cabinett”, mostly written by Manfred Herrman based on pictures of my cameras. Let me know if I could provide any stuff, cheers

Hubertus

I have a werra and I think about using it more often. I take it out, look at it, play with the shutter and then put it back on my shelf. I never quite get around to using it. I am lucky mine is in good condition. I also have both parts of the lens hood. You have to remember to put it back on with the lens set to infinity, many are cracked due to that. Lovely article, thanks Mike.

With the one in this article being a loaner, I honestly think that if I owned it, I likely would do as you did, Peggy. Pick it up, admire it’s looks and simplicity, but then put it down to shoot something else. I am not ignoring other people’s requests for me to come back and give one of the later Werras a try though. If I ever come across a nice Werramatic, I might have to do a follow-up Werra review!

I inherited the Werra that my father purchased in Spain in the early 60’s. I remember finally being allowed to shoot with it as a teenager in the late 70’s, and how fascinating it was to focus with a rangefinder for the first time.

Until I read the comment thread on this page, I really didn’t know which model I have. Thanks to Terry B. for the link to the French page, I now know I have an early (1961) Werramatic.

Anyway, my favorite feature is that both the aperture and shutter speed are on the lens. You have to press a tiny lever on the aperture ring to move it separately from the shutter speed ring. If you don’t press that small lever, the two rings are coupled together, so that changing either the speed or the aperture moves the other to keep overall exposure the same. That was a godsend to me in the days before I understood the relationship between aperture and shutter speeds! Secondly, I’m naturally left-eyed, so I liked using my left hand to advance the film instead of having to take my eye away from the viewfinder to have room for my right thumb to do it. (Hello M2, I’m looking at you!)

I’m going to have to load up the Werra again now. 😀

The Werra is not exactly a rare camera, more than 600k of them were made. The vast majority were sold in Eastern Germany, and especially there you can find these cameras easily and everywhere. The wide and tele lenses are much more rare, though, only 18k Flektogons and 23k Cardinars have been sold.

The olive (not green) cover is not made of vulcanite, but is so-called Buna, a special synthetic rubber. I think they took the olive color, because they could co-use this cover as it was already used by CZJ for some of their binoculars of that time.

The Werra you’ve tested was the very first version of its kind. There have been many improvements to them over time, as some others mentioned. The Werra 1 and 2/Werramat are available here in Germany easily for around 20 € in workable condition, the more advanced Werras 3,4, and 5/Werramatic with exchangeable lenses usually go for something between 50 and 100 €. With a little luck you can get a working one of those for less than 50 €. The wide and tele lens usually are offered for between 50 and 150 € each, regardless of their state. I paid 50 € each for mine, both in very good condition.

While the cameras themselves mostly are in good shape, especially the shutter often needs a CLA to work again as intended.

To me, the Werra 3 and 4 retain most of the simplicity and design of the original Werra 1, but add a coupled rangefinder and/or light meter to the camera, plus a very improved viewfinder. Due to size, weight, quality of the rangefinder and viewfinder and of course of the lenses, I prefer those cameras even to a rangefinder Leica or Contax. My Werra 4 is the only 35mm rangefinder I kept, after I more or less completely switched to medium and large format photography.

Just a very quick comment on a fascinating article.

For the early Werras without a rewind crank, the knob pulls out approx. 10mm so that it can easily be turned between thumb and forefinger when rewinding the film.