This is a Topcon R, a 35mm single lens reflex camera made by Tokyo Kogaku in Tokyo, Japan between the years 1957 and 1960. The Topcon R was Tokyo Kogaku’s first 35mm SLR and like their later RE series, used the Exakta bayonet mount and had interchangeable viewfinders. The Topcon R was a very heavy and solidly built camera and was marketed towards the professional photographer. Although sharing the same lens mount with the Exakta, not every lens would work on it, nor would most Topcon lenses work on Exakta bodies. When exported to the United States, the Topcon R was sold as the Beseler-Topcon B.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 5.8cm f/1.8 Auto-Topcor coated 6-elements in 4-groups

Lens Mount: Exakta Bayonet

Focus: 1.5 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Interchangeable SLR Pentaprism

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: PC Port F and X Flash Sync

Weight: 1035 grams (w/ lens), 765 grams (body only)

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/pdf_files/beseler_topcon_r.pdf

Manual (similar model): https://www.cameramanuals.org/pdf_files/beseler_b_topcon.pdf

Manual (booklet): https://www.cameramanuals.org/pdf_files/beseler_topcon_b_booklet.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Topcon R was one of the earliest professional level Japanese cameras, being released a year before the Nikon F. It is a big and heavy camera with rugged build quality and excellent lenses. With interchangeable viewfinders, a great selection of native Japanese lenses, support for Exakta bayonet lenses, and modern features like an instant return mirror the Topcon R is one of the best early Japanese SLRs. I really enjoyed shooting mine and although I ran into some age related issues, got excellent results from it and would consider a full CLA down the road. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 30% | |

| Bonus | +1 for excellence in quality and performance | ||||||

| Final Score | 14.0 | ||||||

Topcon originally formed in 1932 as Tokyo Kogaku Kikai K.K. which translates in English as Tokyo Optical Company, Ltd. The new company was a dependent subsidiary of Hattori Tokei-ten which had a precision manufacturing branch called Seikosha who themselves would eventually be known as Seiko. Tokyo Kogaku would remain a dependent of Seikosha until 1947 at which time would become it’s own entity.

Throughout it’s most prominent years, Tokyo Kogaku would follow a very similar path to another Japanese optics company, Nippon Kogaku (who would later become Nikon). Tokyo Kogaku was originally established as an optics company who was the sole supplier of optics equipment to the Imperial Japanese Army. Nippon Kogaku was the primary optics supplier to the Japanese Navy making the two companies the foremost Japanese optics companies prior to World War II.

Also like Nippon Kogaku, Tokyo Kogaku would start developing lenses, scopes, binoculars, and other equipment for the military, and would also be a third party supplier to other companies but wouldn’t market it’s products directly to the public, at least not at first. It’s earliest products were three and four element lenses known as the State, Toko, and Simlar. After World War II, the company would branch out to lenses using the Leica Thread Mount for Leotax cameras.

Unlike Nippon Kogaku however, whose first attempt at their own camera was the hugely successful Nikon S rangefinder from 1948, Tokyo Kogaku’s first attempt was far less successful. In 1937, a camera called the Lord was released, a solid bodied 6×4.5 medium format rangefinder with a collapsible lens. It is estimated that only 50 were ever made between 1937 and 1938 and that production was halted due to an outbreak of war between Japan and China. Some historians believe this to be only part of the reason, as the Lord was known to be poorly built and unreliable. This 1937 Lord camera should not be confused with another Lord series of cameras made in the mid 1950s by Okaya Kogaku who was also a child company of Seikosha. Apparently, they liked the name “Lord” so it was re-used on this completely unrelated camera.

The only other camera made by Tokyo Kogaku prior to the war was the Minion, a horizontally folding strut camera that took 4cm x 5cm images on 127 film. The Minion was much more successful than the Lord as it was made until 1943 and then again shortly after the war.

After Word War II, Tokyo Kogaku would release a 35mm version of the Minion called the Minion 35, and a 6×6 TLR called the Topcoflex. The Topcoflex would be the first time the letters “TOPCO” would be used in any products made by the company, hinting at their eventual change to Topcon.

During my research for this model, I could not find a lot of information about the success of these early cameras, but based on how little info there is, I have to guess they probably weren’t that successful. It is likely that like Nippon Kogaku, Tokyo Kogaku focused most of it’s effort on supplying the Japanese military, but as a result of the de-militarization of Japan after their surrender in the war, the company was forced to grow its portfolio into consumer oriented goods.

Perhaps in an effort to stand out from the crowded medium format and 35mm rangefinder market in Japan, in the mid 1950s Tokyo Kogaku would begin work on their own 35mm SLR camera. The new camera would be released in 1957 and called the Topcon R. It was unique among Japanese cameras in that it used the Exakta Bayonet mount used on Ihagee Exakta cameras. Tokyo Kogaku likely wanted to aim for the top of the market with their new SLR as the Exakta was the preferred SLR choice for professional photographers of the era. There was an abundance of Exakta mount lenses already available for it, allowing for an easy transition from someone who already had an Exakta system and was curious about a Japanese model.

When it sold in the United States as the Beseler Topcon B, it had a retail price with the 50mm f/1.8 or 35mm f/2.8 Auto-Topcors of $295, which when adjusted for inflation, compares to $2780 today which was quite a high price for a first camera by a company that at the time was not well known to Western photographers.

The Topcon R was a robust and heavy camera that was significantly larger than competing models. Like the Exakta SLR, it used a cloth focal plane shutter, a front mounted shutter release, and had interchangeable viewfinders. The camera was such a success that the company would cease production of all other cameras, and would focus solely on 35mm SLRs from that point.

The Topcon R series would be in production until 1963, receiving two updates in 1960 and 1961 which were known as the RII Automatic and RIII Automatic. Both cameras added a self-timer and a new linkage to the lens mount for the automatic diaphragm, eliminating the need for an external button. Both cameras can easily be identified by the word “Automatic” engraved on the front face of the prism. The RIII Automatic differs by having a clip above the shutter release for a coupled meter and a revised shutter speed dial with slow and fast speeds on the same dial.

All three versions of the Topcon R were exported to North America where the original version was sold as the Beseler Topcon B and both the RII and RIII Automatics as the Beseler Topcon C.

In 1963, the Topcon R’s successor, the RE Super was released. Building on the success of the RIII Automatic, the RE Super received a redesigned body and an innovative behind the mirror exposure meter.

The RE Super was the first SLR with through the lens (TTL) metering, beating the Pentax Spotmatic by more than a year. In order to achieve in-body metering, the reflex mirror had a pattern of etched clear lines that allowed 7% of light from the lens to pass through to the CdS meter. This was uncharted territory at the time as every other metered SLR required an accessory, or externally mounted meter. Even the Nikon F, which was already on the market at the time, required the use of a separate viewfinder with a self-contained meter. Nippon Kogaku would not release a Nikon branded SLR with an in body meter until the Nikon EL2 in 1977.

In the mid 1960s, Tokyo Kogaku was near the forefront of the photographic world with back to back releases of very successful SLR systems. Unfortunately, the RE Super (and it’s variants) would be the company’s last success as later cameras, especially those from the UV series of leaf shutter SLRs, stopped innovating with new features and sold poorly.

Within ten years after the release of the RE Super, with smaller and lighter weight cameras coming from Olympus, Asahi, Canon, Minolta, and Konica, all using more and more electronics, Tokyo Kogaku quickly found them playing catch up, a game they would never win.

Tokyo Kogaku would attempt to modernize the RE Super in 1977 with two newer models called the RE 200 and RE 300, but it was too little too late. Quality control became an issue, and their reputation as a slow to innovate company basically killed any attempt at a resurgence. Tokyo Kogaku would stop sales of new cameras in December 1980, but would continue to produce a few models rebadged under different names.

Today, most collectors are aware of the excellence of the RE Super and it’s variants, but not so much the earlier cameras. Perhaps not enough is written about the similarities between the R and RE Super as the only major difference (aside from cosmetics) is the lack of a meter. Both cameras share the same large body with great build quality and even more excellent lenses. The Topcon R is a massive camera that just might be the right camera for you.

My Thoughts

Whether you’re a long time reader of this site, or just an experienced camera collector, you probably already know Topcon SLR like the RE Super and Super D are very, very good. These cameras were built to compete with the mighty Nikon F, and earned themselves a contract with the US Navy as their preferred camera. With some of the best SLR lenses of the era, in body TTL metering, and a rugged and incredibly smooth film transport, there was a lot to like about these cameras.

The Topcon RE-series was definitely good, but what about the models that came before it? Tokyo Kogaku had been making SLRs for five years before the RE Super, so maybe those were good too. This was the question I was asking myself when I had first saw a Topcon R. Although differing only in the letter “E” in it’s model name, externally, the Topcon R looks like a completely different camera.

The example I picked up for this review seems to have led a rough life. The camera showed heavy signs of wear and quite a bit of verdigris in it’s various crevices, but it worked perfectly. I don’t have any verifying statistics to back this up, but in my time collecting and shooting old cameras, I believe there to be a correlation between cameras that show heavy signs of use (not abuse) and still work correctly, compared to mint cameras that are seized up.

My first impression of the Topcon R is that this is a large camera! Compared to the Topcon RE Super, the peak of the pentaprism is slightly taller than the flat top of the RE and quite a bit wider. Depth front to back is about the same, with the RE Super’s more squared off edges giving it a thicker appearance, when in reality, the two cameras are about the same in this measurement. On the scale and with each’s respective lens, the Topcon R is slightly heavier at 1055 grams compared to the RE Super which weighs 1039 grams. This difference of course can only be seen on a scale however, as in the hand, both cameras are behemoths.

Where the Topcon R really shows it’s gargantuan proportions is when it is compared to some other camera, like the Pentax K, which was also available in 1958, the same year as the Topcon R.

Looking at the top of the camera the Topcon R looks like most other 1950s Japanese SLRs. Starting from the left we have the fold out rewind knob and film reminder dial, which both sit atop a removable accessory ring. The Topcon R lacks any kind of flash shoe, but you can attach a specially designed flash bracket to this knob by unscrewing the chrome ring around the film reminder dial.

To the right of the accessory ring is a lever for selecting between X and F flash sync, and a button for releasing the interchangeable viewfinder. Press this button and the pentaprism slides off the back of the camera. This method for attaching the viewfinder is superior to those used by Ihagee on the Exakta and Nippon Kogaku on the Nikon F which both lift up.

To the right of the prism is the shutter speed dial which has speeds 1/30 through 1/1000 plus B and X speeds on top, and a separate collar around the base for slow speeds from 1 second to 1/30. In order to use the slower speeds, you must set the top ring to the 1-30 setting, and then pick a slower speed with the ring below.

The shutter speed dial is a two piece design that can be set before or after cocking the shutter. Simply lift up on the dial and rotate it to whatever speed lines up with the black arrow. Be careful though as firing the shutter causes the shutter speed dial to rotate, so you must avoid any contact with this dial or else it will throw off the shutter speeds.

Finally, on the far right is the combined film advance lever and exposure counter. The counter is additive, showing how many exposures have been made, and must be manually reset after loading a new roll of film.

Flip the camera over and there’s not much to see on the bottom. A 1/4″ tripod socket is centrally located beneath the shutter, which is a very good thing as the weight of the camera, plus it’s lenses would definitely cause stability problems on a tripod if it wasn’t centered.

Off to the side is the rewind release, which is in the form of a knob, that must be pressed in and rotated in the direction of the arrow. Although this requires a bit more dexterity than a simple button like on most cameras, I actually like these style of knobs as they all but eliminate any chance that the camera can be accidentally put into rewind mode.

Looking at the Topcon R from the side gives another look into how massive this camera is, as it’s dimensions are larger than that of most other 35mm SLRs. The left side has the release latch for the film compartment, and immediately above it is the PC flash sync port. From this side you can also see the lens mount release lever and the Auto-Topcor lens’s semi-automatic diaphragm lever.

From behind, there’s not much to see other than the round opening for the viewfinder and a “Tokyo Kogaku Japan” engraving. The eyepiece for the viewfinder appears to have internal threads, suggesting that perhaps some type of diopter adjustment lens or right angle viewfinder might have been available, but no such accessories are present in any of the Topcon R literature I’ve found.

The film compartment is like that of most other cameras of the era, just a bit larger. Film transport is from left to right onto a single slotted and fixed take up spool. The film door has a smooth black painted pressure plate and a roller to maintain film flatness as it travels across the film plane.

The light seals in the Topcon R are made of yarn in the door channels and fabric on the hinge side as it predates the use of foam light seals. The seals on this example appeared to still be in good shape and did not require replacement.

The Auto-Topcor lens that would have come standard on the Topcon R has a semi-automatic diaphragm. Semi-automatic lenses differ from fully automatic lenses in that when selecting a desired f/stop for the lens, the diaphragm doesn’t open up until you manually activated it with a lever on the lens.

Semi-automatic lenses like these were a stop gap used by lens makers like Carl Zeiss, Asahi, and many others. With the lens manually opened, the lens is wide open, allowing the maximum amount of light into the viewfinder for the brightest possible composition. When it comes time to press the shutter release, an external button on the lens, which cover’s the camera body’s front mounted shutter release. first stops down the lens to the desired f/stop moments before triggering the shutter to fire.

In use, semi-automatic lenses work the same way as fully automatic ones, as long as you remember to keep pushing down on that lever before each and every exposure. If you aren’t bothered by a darker viewfinder, or just really like previewing depth of field, you can skip this step and use the camera normally.

When changing f/stops, the aperture ring has a locking feature which requires you to press a small chrome button opposite the side of the aperture scale before you can turn it. You can see this button in the image above of the bottom of the camera. When I first acquired this camera, I did not realize this was how it worked, and I assumed something was wrong with the lens as I couldn’t turn this ring. If you come across one of these lenses, don’t force it, just be sure to press the chrome button.

The Topcon R uses the Exakta bayonet mount, which was chosen at the time of this camera’s release to maintain compatibility with a huge number of Exakta lenses that were already available. Tokyo Kogaku likely knew that they’d have a much easier job attracting customers interested in buying a new SLR from a Japanese company they might not have heard of, if it meant their existing lenses would work with it.

In reality, the Topcon isn’t compatible with 100% of Exakta lenses. Those with an automatic diaphragm will not support that feature as the Exakta’s shutter release is on the photographer’s left side whereas the Topcon is on the right and the buttons won’t line up. You can still physically mount these lenses and either just not use the automatic feature, or try to trigger them with two separate fingers.

Beyond semi-automatic lenses, some will not work at all. In my review for the Topcon RE Super, I comment about the Schneider-Kreuznach Xenon lens in Exakta mount which hits the mirror when focused to infinity.

The use of the Exakta mount likely helped the Topcon gain some exposure, and it’s very possible the company wouldn’t have had the success they did if they went with their own proprietary mount like other Japanese SLRs did, however the use of the Exakta mount, with it’s narrow opening, proved to be a problem later on down the road as it made developing faster and wide angle lenses difficult.

When used with an Auto-Topcor lens, a threaded shutter release button on the lens lays over a shutter release on the camera’s body. A small gap between the two allows you to press the shutter release on the lens and stop down the diaphragm moments before firing the camera’s shutter. When used with Exakta lenses or those without the semi-automatic diaphragm, you directly press the shutter release button on the body to fire the shutter. This external coupling of the lens to the body for the automatic diaphragm was unique only to the first Topcon R. In 1960 and 1961, the Topcon RII Automatic and RIII Automatic switched to an internal coupling, but maintained backwards compatibility with older lenses.

Upon it’s release in 1958, the Topcon R was a pretty advanced camera, with features like an instant return mirror, rapid advance lever, and support for semi-automatic lenses, but one area in which the camera really shows it’s age is in it’s viewfinder. The below gallery shows two shots through the Topcon R’s viewfinder, one in and out out of focus so you can better see the focus aide in the center.

Looking through the viewfinder, you see a ground glass with a large split image focus aide in the center….and that’s it. Unlike the Nikon F which was still a year away from it’s release, the Topcon R doesn’t support interchangeable viewing screens. You can remove the pentaprism and attach a hood, but beyond that, there’s nothing else to see in the viewfinder. Image brightness is not even across the entire image, with noticeable vignetting in the corners, even with the lens wide open. This is not an issue outdoors, but in low light, or with slower f/2.8 or f/3.5 lenses attached, the image can get quite dark.

For it’s time, the Topcon R had a lot of things going right for it. It was a modern SLR with a selection of excellent Topcor lenses, support for many Exakta lenses, a robust build quality, and a long list of features. Most importantly, it beat other companies like Nippon Kogaku (Nikon), Canon, Yashica, and Konica into the world of 35mm SLRs. Comparatively, the Topcon RE Super is a better camera, but it also came five years later. For a 1958 SLR though, there is a lot to like on paper, but what is it like to shoot?

My Results

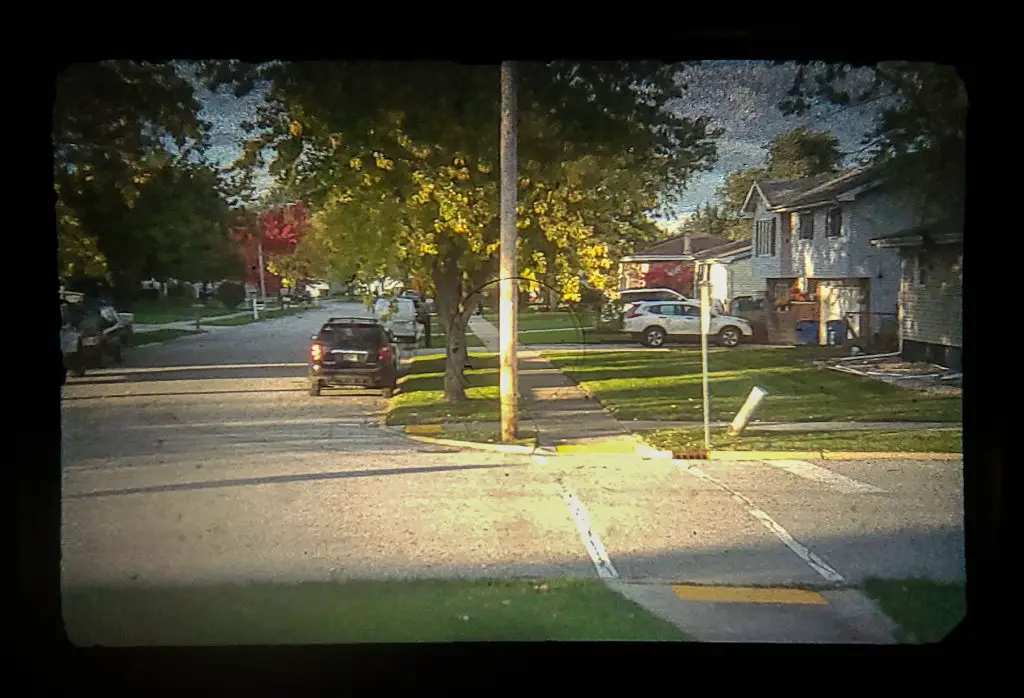

For the first roll through the Topcon R, I went with some Kodak Plus-X 125 that I had been on a kick shooting in mid fall of 2021. While my two favorite black and white films have been TMax 100 and Panatomic-X, I like the more noticeable grain and newspaper like contrast of Plus-X and found that I was enjoying it’s differences a little more compared to those other two films. Of course, it never hurts to shoot a 125 film in a camera with a 1/125 shutter speed that makes Sunny 16 incredibly easy to do.

True to my experience with the later Topcon RE Super, the results I got from the Topcon R were just as excellent. I guess it should be no surprise to see similar results from two cameras using one of Tokyo Kogaku’s excellent Topcor lenses. The Auto-Topcor being an older design mechanically, but I believe it to be the same optically as the later lens.

Images show incredible sharpness corner to corner, with excellent fine detail, resolution, and contrast. The earlier Auto-Topcor is absolutely worthy of the same praise heaped upon later Topcor RE lenses. It is clear that a couple extra years of age has done nothing to tarnish this lens’s performance.

Sadly, this Topcor R body wasn’t in as great of shape as it’s lens as the shutter shows noticeable capping in many images where the right side of the image is darker than the left. This of course is typical of older focal plane shutters in need of servicing, and in no way affected my opinion of this camera.

The Topcon R is big and heavy, which for people with small hands might find cumbersome, but I had no issues. The front shutter release was comfortably located, and despite sticking out about half an inch forward from the camera’s actual button, didn’t cause me any trouble. Focus motion of the Auto-Topcor was smooth as was the film transport. I don’t know if I’m just lucky, but both this and the later RE Super have two of the smoothest actions of the film advance lever of any camera I’ve used. Maybe the Leicaflex is better, but they’re very close.

Finally, despite lacking any information in the viewfinder, I found the size and brightness of the focusing screen and the inclusion of a very large split image focus aide to be enjoyable. I had no problems seeing the edges of the image while wearing prescription glasses and although not as bright as a 1980s SLR, composing the image in heavy shadow was not a problem for me.

If there was one nitpick about the camera that I didn’t love, it was the aperture lock which requires you to press and hold a tiny button around the lens to change f/stops. The issue isn’t necessarily in difficult, rather inconvenience as the location of the button changes as you turn the ring, so whether you have the lens wide open or stopped down all the way, you have to fumble about for a second or two while trying to locate it.

Beyond that, the camera was an absolute pleasure to use. After seeing the quality of the images I got from it, I would have normally shot a second or even third roll in this camera, but the shutter issues held me back.

As I review cameras, I don’t always have luck with them, many don’t work, but I continue with the review anyway because I can almost always look past conditional issues and give my opinion on how a camera should work when in proper order. In the case of cameras like the Topcon R that have some issues, I have to be discriminate about which ones I would send out for servicing, as I simply cannot afford to CLA every non-working camera I own, but this is one of the very few which I will still consider doing. The Topcon R is so good, it is worthy of being fully serviced once I get around to it.

Most collectors are aware of how good later Topcons like the RE Super or Super D are, but for anyone whose never considered the earlier models, I feel as thought despite some conditional issues with this one, in good working condition, the Topcon R is as good as those later cameras, and might even be the best looking camera of the bunch.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

https://retinarescue.com/topconr.html

http://exaktaphile.net/captjack/praktina/Topcon%20Cameras.htm

http://www.pentax-slr.com/181841704

http://www.topgabacho.jp/Topconclub/FPslr1.htm (in Japanese)

Topcor lenses are still highly valued in the digital realm as indicated in prices on eBay.

Stellar review! Looks like a real tank of a camera, and a lovely bit of history.

Thanks for the compliments, Jack!

Bravo, great article. I saw my first Topcon Beseler RE super D in the USN at a Naval air station in 1970 inside a anti submarine warfare plane. I was very familiar with SLR cameras, but not this one. I was a Pentax H1a user in those days. I was impressed, and it had the US Navy stamp on the bottom. I didn’t see another Topcon RE Super until 1990 at a camera show. Years later , and many servicing jobs on Topir re auto lenses, I am still impressed by the build quality and the outstanding optical quality. Today I serviced a Red Dot 5.8cm/1.8 black #9900×××× and thought this odd, where’s the green dot? Well after doing research, black lenses with green dots are in the the 1100xxxx serial number range. So the Black Topcon RE Super 46A build , came with a matching black normal lens having a red dot. It’s a early version, quite rare. Normal to this build date were chrome bodied lenses. I have many black 58mm topcor lenses but none have I ever seen with this serial #. Don@ Eastwestphoto

Thanks for the comments! Interestingly, you’re the second ex-Navy photographer who has contacted me recently! It’s always awesome to hear stories from the men and women like you who were out there shooting these wonderful cameras!

Mike,

Again a re auto topcor lens in black , 5.8/1.4 #942401, is not in the books. 94A build 100%, but found on a black re Super with a strange serial # 4635871. My research is extensive, but no info makes sense. I believe it’s a special order camera body and lens.

Very nice article, I didn’t collect Topcon cameras until now. But as a Nikon collector I have to correct one point: the first SLR with fixed TTL metering was the Nikkormat FT which came out 1965. The Nikkormat series was produced until 1977. Nippon Kogaku’s first electronic autoexposure camera, the Nikkormat EL, came out 1972.

Thanks for the compliments, but you are not correct. Both the Topcon RE Super and the Pentax Spotmatic beat the Nikkormat FT to the market with TTL metering. I have a thorough review of the Nikkormat FT3 on the site which also covers the history of the entire Nikkormat brand. Here is a link:

https://mikeeckman.com/2022/06/nikkormat-ft3-1977/

Mike,

The model RS is missing from your most excellent article. I own this camera model and I have been looking for its accessory light meter. To your knowledge did Beseler import the RS model into the USA? Ebay sales seem to show, UK has had sales in this model, but not USA? Model 32A RS=1962, model 46A Super D=1963, seems Beseler knew model #46A, was coming out and choose to import the more profitable 46A? Regards, Don