This is a Great Wall DF-3, a medium format SLR made by the Beijing Camera Company in Beijing China starting in 1984. The DF-3 shoots 6cm x 6cm images on 120 format roll film and is part of the DF-series of SLRs that are loosely inspired by the KW Pilot 6. The DF-3 adds a self-timer to the earlier, and more common DF-2. The camera has an interchangeable lens mount that is physically the same as the M39 Leica Thread Mount, but due to a much longer flange focal distance, can only focus to a couple of inches. The Great Wall DF-3, like most Chinese cameras of this era is cheaply made and was several decades out of date compared to other cameras being made at the time, but is of just good enough quality to be a capable shooter.

Film Type: 120 Roll Film (twelve 6cm x 6cm exposures or sixteen 4.5cm x 6cm with mask, per roll)

Lens: 90mm f/3.5 Great Wall coated 4-elements in 3-groups

Lens Mount: M39 Screw Mount, Great Wall Flange Distance

Focus: 1 meter to Infinity

Viewfinder: Waist Level Reflex Viewfinder

Shutter: Metal “Guillotine” Shutter

Speeds: B, 1/30 – 1/200 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Other Features: Self Timer, Magnifying Glass

Weight: 922 grams (w/ lens), 726 grams (body only)

Manual: None

How these ratings work |

The Great Wall DF-3 is one of the least expensive ways to get into a medium format SLR. The camera is quite basic, offering limited shutter speeds, but it’s simplicity also means that most should still be in working order today. Although using the M39 lens mount, using rangefinder lenses is only good for extreme macro shots, but with the included 90mm Great Wall lens, it produces images with nice sharpness and just the right amount of optical flaws to add some character to the images. This is a fun camera and well worth owning. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0% | |

| Bonus | +1 for great value, the cheapest option in medium format SLRs | ||||||

| Final Score | 9.0 | ||||||

History

In my earlier review for the Seagull 203 camera, I introduced the Chinese camera industry as one shrouded in mystery, saying that with few exceptions, much of the history of it’s camera makers has been lost to time. Using a book called “Cameras of the People’s Republic of China” by Douglas St Denny, I was able to learn more about the various Chinese camera factories than I could find on any website. If you’d like to learn more about the history of Chinese camera makers, I recommend you check out that post as I do not want to duplicate too much here.

In the second half of the 20th century, a large number of Chinese made cameras used the name Great Wall. The use of names like “Great Wall”, “Five Goats”, “Seagull”, and “Happiness” come out of a desire by the Chinese government to instill confidence and national pride into Chinese made goods.

Most early Chinese cameras were copies of existing Japanese or Soviet designs, which themselves were copies of German cameras. China went through a great deal of political turmoil which is far beyond the scope of this article, but from what I learned while reading St Denny’s book is that things with Western influences were frowned upon, so names that evoked Chinese imagery were preferred.

The name “Great Wall” was used by a series of camera factories in Beijing, China. The first such factory was formed either in late 1949 or early 1950 and was eventually called the Da Lai Precision Machine Shop. The name “Da Lai” loosely translates to “very popular” suggesting a level of propaganda in an effort to establish itself as a market leader.

Da Lai’s first products, like many burgeoning photographic operations was making tripods and other photographic goods. It wouldn’t be until 1955 or 1956 when the first Da Lai 35mm camera was made, which was a Chinese copy of the Zorki rangefinder. The Chinese factory built the camera body, shutter, and housing for the lenses in Beijing, but lacked the ability to produce glass lenses, so those produced for the Zorki were used. Since the Da Lai 35mm camera was built to exact Soviet specifications, swapping lens elements was not a challenge. It is thought that a total of 12 of these Da Lai 35mm cameras were produced, only one of which is known to exist today in the museum of the current day Beijing Camera Factory.

A coordinated announcement of the release of China’s first camera was made on August 4, 1956 in a variety of Chinese publications. The announcement included photographers of Chinese workers assembling the cameras, sample photos said to be made by the cameras, and a large amount of praise for the camera’s high quality.

Around the same time as the development of the Da Lai 35mm camera, a second camera which was a copy of a Japanese Ricoh TLR was being worked on but never finished. Despite receiving a huge amount of support by the Soviet Union, the Republic of China was going through a period of great instability. The Da Lai Precision Machine Shop was both privately and state owned, which caused there to be a huge amount of worker turnover.

Shortly after the release of the Da Lai 35mm camera, the Chinese government assumed complete control over the factory and renamed it to the Beijing Camera Factory, the name it still uses today. The first camera produced by the nationalized Beijing Camera Factory was made around 1957 and was called the Rainbow, which looked very much like the Dai Lai TLR prototype created earlier. The Rainbow was only made for one year and according to St Denny’s book, around 7600 were thought to be made.

In the years that would follow, the factories in Beijing continued to release new models. A second TLR called the Temple of Heaven based off the Japanese Yashica A and a medium format Bakelite camera called the Leap Forward based off the Dufa Pionyr from Czechoslovakia were all made around this time.

In 1968, at a time known as the Cultural Revolution, a new camera called the Red Dawn was being developed. The Red Dawn was a copy of the Japanese Ricoh Super Shot spring wind rangefinder. Before it was officially released, the new camera was renamed the Beijing SZ-1 and featured slogans such as “Serve the People” and “Long Live Chairman Mao” engraved into the camera and also on printed material relating to the camera.

Fearing that such engravings and the Beijing name might offend people from other Chinese provinces, in 1969, the camera was renamed the Great Wall SZ-1, a name that would be used over and over on many future Beijing produced cameras.

The Great Wall SZ-1 and the slightly improved SZ-2 were very popular cameras both in Chinese markets and some Chinese friendly export markets and remained in production until 1980. When he wrote his book in 1989, Douglas St Denny claimed that although the Great Wall SZ-1 and SZ-2 could no longer be purchased new, it was very easy to find in second hand shops as there were a huge number of them around.

By the mid 1970s, the Beijing Camera Factory had exceeded the capacity of the original factory and was forced to relocate to a much larger facility to the northwestern suburbs of Beijing behind the Big Bell Temple. With more space and a more modern facility, the Beijing Camera Factory branched out into areas besides camera production, including microfilm and photo copy machines.

By the mid 1970s, the Beijing Camera Factory had exceeded the capacity of the original factory and was forced to relocate to a much larger facility to the northwestern suburbs of Beijing behind the Big Bell Temple. With more space and a more modern facility, the Beijing Camera Factory branched out into areas besides camera production, including microfilm and photo copy machines.

Around 1980, a prototype for a medium format SLR, based on the KW Pilot Super 6 from 1939 was produced. No name for this prototype was ever given, but in 1981 when it went into production, it was called the Great Wall DF-2, suggesting the prototype might have been the DF-1. Exactly why a Chinese camera maker in 1980 would consider making a new camera based off a design from more than 40 years early, especially when the factory was already producing much more capable and technically advanced cameras is unknown.

Although the Great Wall DF-2 and the KW Pilot Super 6 share some of the same attributes, they did not share the same lens mount. Both the Pilot Super 6 and the DF-2 had interchangeable lenses, the KW camera had a smaller 32mm mount, whereas the DF-2 used a larger 39mm mount.

The shutter was a “guillotine” type in which a baffle connected to the reflex mirror doubles as one of the shutter curtains. Cocking the shutter also lowers the mirror which blocks light from entering the film plane. Firing the shutter raises the mirror which also opens the shutter, and a second baffle follows close behind to close it again. A gap between the mirror baffle and the second baffle momentarily allows light to pass through exposing the image. A similar design was also used by Ihagee in their lower end Exa series which began production in 1951. The benefit of this style of shutter is that it is simple and with so few moving parts, is fairly reliable. The biggest drawback however is that you’re limited in the number of speeds.

Watch the slow motion clip of the shutter in the DF-3 firing at 1/30. At the start of the clip, the mirror is already lowered.

In addition to the curiosity of why the Beijing Camera Factory copied such an old camera, it’s decision to use the M39 mount is just as strange. The Great Wall DF-2’s mount is physically identical to the Leica Thread mount. Both the diameter and thread pitch are exactly the same, meaning that you can physically screw a Leica lens into the DF-2, but because the distance from the lens mount to the focal plane is much different, using Leica rangefinder lenses on the DF-2 only allows for focus up to a couple of inches.

Perhaps answering the question of why this camera was made, the Great Wall DF-2 sold well as it was very inexpensive and simple to use. In 1984 and 1985 two updated models entered production called the Great Wall DF-3 and DF-4 respectively. The two updated models were very similar to the original model, with the only changes being the addition of a self-timer and revised name plate to the DF-3, and a flash synchronization port, a hot shoe, and a secondary slider for the 4.5×6 exposure window on the back of the camera to the DF-4. A DF-5 model was reportedly in development during the end of DF-4 production that had a more advanced 5 element lens with front cell focusing, but only a very small number were ever made and none were sold.

By the mid 1980s, the market for medium format cameras in China had dried up. Inexpensive 35mm cameras and film minilabs from Japan meant that people could buy simpler and cheaper cameras from Japan than use something as clunky as the Great Wall DF-series, causing the line to be discontinued.

Douglas St Denny’s book was published in 1989, so his information stops there, and with how difficult it is today to learn about the history of most Chinese companies, I honestly have no idea what happened next. A Google search finds companies in Beijing that make cheap digital cameras today, but I have no idea if these modern companies share any lineage with the ones that produced cameras like the Great Wall DF-3. Maybe they do, maybe they don’t.

If I had to guess, I am sure that the company kept making film cameras, largely based off those from Japanese models. We know that other Chinese camera factories copied several different Nikon and Minolta designs, so there’s no reason to believe they suddenly stopped doing it in the 1990s.

Today, there is a small but growing number of those who collect Chinese cameras, not necessarily because they’re better, or offer anything that other American, German, Japanese, or Soviet camera makers didn’t, but more because of how obscure they are. If you are the type of person who likes “the thrill of the chase” then collecting Chinese cameras might be for you as there are a heck of a lot of them out there, but they’re very hard to find.

The Chinese camera industry is very complex and rich in history, but as you can see, most of that history is lost today and likely will never be fully understood. Cameras like the Great Wall DF-3 are relatively easy to find, making them good additions to any collection, without having to do so much digging for the more rare models. Combined with the fact that they have a simple design that holds up to the rigors of time and can often be found in working condition today, they can also be pretty good shooters too, if you are interested in medium format SLRs, but don’t want to spend too much money.

My Thoughts

This Great Wall DF-3 came to me like many oddball cameras do, from a reader of this site. Back in July 2021, I received an email from Dwight Anderson who noticed a lack of any Chinese SLRs, and offered me his DF-3 for review. While I’m always open to taking on loaners from readers, when I realized that next Chinese New Year would occur on the same week I normally start releasing new reviews, I thought it would be fun to review this one in celebration of the year of the tiger.

Dwight had said that this DF-3 was in perfect working order and true to his word, when the camera arrived, everything seemed to be ready to go. Being made in the 1980s, the camera wasn’t yet old enough to need light seals or have any other common age related ailment.

The camera strongly resembles the general shape of other 6×6 waist level SLRs of the 1960s like the Komaflex-S and Fujita 66. Unlike more advanced medium format SLRs like the Hasselblad 500C and Bronica S2 that are more deep than they are tall, the DF-3 takes on a shape of a short TLR.

The camera’s build quality is what I would call…not bad. It’s not as cheap feeling as Chinese made “scameras” that were common in the 1980s and 90s, but is a far cry from the quality you’d expect of a German or Japanese camera. With a weight of 922 grams with the lens, the camera has a decent amount of heft, but there’s still quite a bit of rough feeling metal all over the body. Perhaps the most telling design detail of the camera’s quality is the cheap looking silkscreened Great Wall name plate and vanity ring around the lens.

Up top is the hood for the waist level reflex finder. There is no catch pin holding the hood shut, only friction, so all it takes is a gentle upward flick of the hood and it pops up into the viewing position. Behind it is some kind of exposure chart written in Chinese making recommendations of how to shoot ASA 100 speed film with a shutter speed of 1/125 in various lighting situations. To the right of the hood, on the top plate of the camera, next to the right strap lug, is a threaded socket for a cable release.

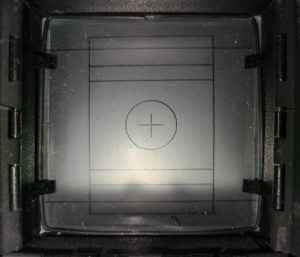

With the viewfinder hood up, the focusing screen is reasonably bright if compared to other 1960s cameras, but compared to other SLRs from 1984, is quite dark. The focusing screen appears to be frosted glass, and lacking in any Fresnel or laser etching pattern to improve corner brightness. Vignetting is strong even in bright daylight and almost completely black indoors. The DF-3 does not have an instant return mirror, so you’ll need to cock the shutter in order to drop the mirror and see through the viewfinder.

On the focusing screen are some various squares and a round circle with a plus sign in the middle of it. No other focusing aides like a split image rangefinder or microprism circle are evident. Two horizontal lines going across the top and bottom quarter of the images are framing lines for using the optional 4.5×6 adapter that originally came with this camera, but I am unsure of the purpose of the various squares printed on the viewfinder as I’ve found no English language manual for the DF-3. My best guess is they were to be used for other accessories available for the camera.

Also like other waist level reflex cameras, the Great Wall DF-3 has a flip up magnifying glass for critical focus.

The magnifying glass is connected to a metal plate that entirely blocks extraneous light from entering the viewfinder, making it very easy to see a high contrast image for precise focus.

Around back is a slider and two doors, one for 6×6 images and the other for 4.5×6 images which are used when using the DF-3’s optional 4.5×6 mask that originally came with it. The metal slider opens both doors at the same time, so after advancing film to whatever next frame is appropriate for the format you are shooting, be sure to close the door to avoid accidental exposure of the film through the paper backing.

The bottom of the camera has a centrally located 1/4″ tripod socket and the film door release.

To access the film compartment, you must slide two metal “ears” around the outer perimeter of the tripod base toward the back of the camera. Doing so, will push forward on a metal clip which is holding the door shut. To close the camera, slide the ears towards the front of the camera, and the clip will move back, holding the door shut. In the image to the left, the ears are in the open position.

The film compartment door is hinged at the top and swings open like a Rolleiflex. A new supply of film is loaded into the bottom of the camera, and wraps around a metal roller, across the film plane, and onto an empty take up spool, positioned near the top of the camera. Since the Great Wall DF-3 lacks any sort of automatic frame counter, there is no need to be concerned with the starting position of a new roll of film. With a new roll of film loaded, once you are certain the backing paper is securely attached to the take up spool, you may close the camera and use the red windows on the back of the camera to advance the film to the first exposure.

That the Great Wall DF-3 has an interchangeable lens mount isn’t all that interesting, but to see that it uses the M39 screw mount is.

Removing and attaching the coated Great Wall lens is the same as any Leica Thread Mount lens, righty tighty, lefty loosey. And although you can physically mount any LTM lens you want, the thickness of the Great Wall camera is much greater, pushing LTM lenses quite a bit farther away from the film plane than they were designed for, which means that you’ll only ever be able to focus closely…very close, to your subject. With any LTM lens, the Great Wall DF-3 effectively becomes a 6×6 medium format macro camera.

Another limitation of mounting LTM lenses onto the Great Wall is that no part of the lens can protrude beyond the screw threads, or else it will bottom out. Using a Nikkor 5cm f/2 lens, the lens needed to be set to a focus distance of 3 feet or less or else I couldn’t mount it to the camera. A Leitz Elmar 5cm f/3.5 lens would only fully screw on if it was at minimum focus.

Note: While shooting this camera, I mounted a Nikkor 5cm f/2 LTM lens and took a few pictures. Check out the image gallery below to see what a LTM lens looks like on the Great Wall DF-3.

The lens itself is rather ordinary, with the aperture ring closest to the body and the slightly thicker focus ring nearest the front of the lens. The aperture ring has prominent click stops at every indicated f/stop from f/3.5 to f/22 and the focus ring is indicated in meters, from 1 meter to infinity. The front of the lens is threaded to accept 52mm filters and caps.

The camera’s left side is where most of the action is, featuring the film advance knob in the upper left corner, combined shutter speed dial and cocking knob in the middle, a small double exposure prevention override, self timer lever in the upper right corner, and shutter release in the bottom right corner.

The Great Wall DF-3 does not have a coupled film transport, but it does have a double exposure prevention feature which prevents you from cocking the shutter until after advancing the film. For intentional double exposures, pressing up on a small button between the two knobs while rotating the shutter knob will allow you to cock the shutter a second time without advancing the film.

Using the red windows on the back of the camera, turning the film advance knob clockwise will advance the film and unlock the shutter speed knob. To change shutter speeds, you must lift the outer portion of the shutter speed knob and rotate it so that your chosen speed lines up with a chrome triangle in the center piece. A red arrow indicates the direction you must rotate the shutter speed knob to cock the shutter. I was able to change shutter speeds both before and after cocking the shutter, but found it easier to do after the shutter is cocked, so that’s how I would recommend doing it.

Caution: When cocking the shutter, you must overcome a spring that wants to return the knob to it’s uncocked state. Be sure that you have reached the limit of this knob before taking your hand off of it, as it will quickly spring back to an uncocked position. If this happens, the double exposure prevention feature will kick in, requiring you to activate the override button to properly cock the shutter again.

To use the self-timer, you must push the lever in the direction of a small arrow on the handle. After pushing it to it’s limit, a small chrome button beneath it is used to activate the timer. Using the main shutter release will not trigger the self-timer.

The shutter release is a small chrome button that slides down to release the shutter. It is in easy reach of your right thumb when supporting the camera with your right hand. The shutter on the Great Wall DF-2 is part of the reflex mirror mechanism, similar to what of the Ihagee Exa, and is not only very loud, but also causes quite a bit of body shake when firing the shutter, so you should make sure the camera is firmly supported when making exposures.

Caution 2: Upon firing the shutter, the shutter speed knob will spin back to it’s original state. You must take care not to let any part of your hand touch this knob while it is rotating as it will throw off the timing of the shutter, causing your image to become over exposed.

The Great Wall DF-3 is a strange camera. It’s design is German but it’s function is Chinese and although built in the 1980s, it is based off a design from the 1930s. The entire camera is one big contradiction, but somehow manages to come together to a single cohesive camera that works quite well.

I didn’t have high hopes for the camera, but was confident enough that it should return some decent results, so I loaded in some film and took it for a stroll.

My Results

For the first roll of film through the Great Wall DF-3, I chose some slightly expired Kodak Portra NC 160 that I had laying around. I took with me a Nikkor-HC 5cm f/2 lens to use to see how the camera performed with a LTM lens mounted. Using this lens, I would only be able to get extreme closeups, but with the reflex finder, I figured focusing and framing the image wouldn’t be much of a problem. I took that and the correct Great Wall lens on a short walk through Crown Point, Indiana near the end of summer 2021.

Pleased with the results from the first roll of Portra, I wanted to give the Great Wall one more go, this time with some slightly expired Shanghai GP3 film. I figured this Chinese film would make for a good pairing in a Chinese camera. Not to mention, I shot this film in early January 2022 in the dead of winter, so a black and white film better suited the environment I was in.

I’ll start off by saying that while there is a “cool factor” of using an M39 rangefinder lens for macro shots on a medium format SLR, in use, it is very difficult to do. For starters, the close focus distance is about 5 inches from the front edge of the lens to your subject. The way the lens mount is designed on the Great Wall DF-3, all three of the LTM lenses I tried needed to be set to minimum focus before screwing them onto the camera as if any part of the lens protrudes beyond the screw threads, it would bottom out. So in other words, you can’t even set the lens to infinity on it’s own focusing scale to get you an extra couple of inches distance on the camera. With a LTM lens on the DF-3, it’s effectively a fixed focus lens to about 5 inches.

Note: After doing this test, but before publishing this article, someone had suggested I use an M39 lens made for the original Zenit SLR which also has a longer flange distance than an M39 lens. While not as long as the Great Wall’s, using a Zenit M39 lens might have given me a little more distance to be able to focus on. It wouldn’t have reached infinity, but might have been good for less extreme close ups. If I ever get a chance to try this, I will update this review.

With the front of your lens 5 inches away from your subject, depth of field is razor thin, meaning that getting anything more than a sliver of your image in focus is very difficult to do, and even more difficult to hold steady. Stopped down all the way in bright sunlight, you might gain half an inch of depth, but nothing more. Try to shoot a flower like a daylily, and maybe the tip of the stamen will be in focus, but the filament below it will be completely out of focus.

I shot the DF-3 with the Nikkor lens four times, and only the images of the dog bones and red flower came out. It was certainly cool, but more effort than it was worth.

When shooting the camera using the lens it came with, I was quite pleased with both the experience and results. Like most other waist level medium format SLRs, the image in the viewfinder is reversed left to right, and on the Great Wall shows noticeable vignetting near the edges. It’s certainly not a problem outdoors, just remember to open the lens all the way while composing and stop it back down before making your exposure. I did not bother trying to shoot the camera indoors as I just didn’t feel like it.

Image quality is good, but considering this camera was made in the mid 1980s, when compared to other medium format and 35mm models of the same era, it is clear the Chinese were still quite far behind. Sharpness is good in the center, but softness creeps up quickly near the corners, and most of my images had noticeable vignetting.

The deep blue lens coating on the lens seems to do a good job of reducing flare and maintaining accurate colors as I saw no flares in any of the bright sunlight outdoor photos I took, and the colors seemed accurate to the Kodak Portra NC 160 I was using.

Overall, the images have a nice distinct look that if someone showed me and asked me to guess which camera shot them, I would have predicted some kind of mid century folding camera with a 3 or 4 element lens, not a 1980s Chinese SLR.

Like the lens, the rest of the camera isn’t perfect either. I could live with the limited selection of shutter speeds as I rarely go faster or slower than the 1/30 – 1/200 the DF-3 is capable of, but the strong tension on the shutter speed dial, and it’s desire to slip out of my hands each time I wound it, was bothersome. I also had concerns with the strong force exhibited by the guillotine shutter, which like the name suggests, is rather abrupt in it’s action. Looking at the images I shot, I didn’t notice any body shake caused by the shutter, but it was something that was on my mind each time I pressed the shutter release.

The Great Wall DF-3 is not a bad camera, and despite my mostly negative comments above, I did actually enjoy using it. The selection of inexpensive medium format SLRs is not very big these days, so for those wanting to get into this style of camera, the Great Wall is a good option. But once you do, you will never mistake it for a German, Japanese, or even Soviet made camera as nearly everything about the operation of this camera is a little less refined.

If that’s OK with you, then by all means go ahead and buy one. I will say that the simple operation of the camera probably means that most should be in working condition as apart from subjecting it to physical damage, there isn’t much to break on it. I think you’ll find, just as I did, that for the money, the Great Wall DF-3 is a capable and economical entry into the world of medium format SLRs.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Great_Wall_DF

http://www.heayes.com/greatwall.htm

https://cameralegend.com/tag/great-wall-df-review/

http://moominsean.blogspot.com/2008/06/great-wallthe-camera-not-wall.html

https://inauspicious.org/cameras/df4/

https://www.lomography.com/magazine/216077-rare-and-funky-the-great-wall-df-camera-a-true-lomo-jewel

http://web.archive.org/web/20060708153446/http://www2.xitek.com/info/showarticle.php%3Fid%3D1931 (in Chinese)

Thank you for an interesting review of another obscure camera. I’d like to find a Zi Jin Shan one day to shoot. Years ago I had a KW Pilot 6. That camera was built like a tin can; IMHO the Great Wall is likely no less solid-feeling or more clunky than the Pilot original. The Pilot 6’s side panels were subject to flexing if squeezed even gently. I had to take great care with the film door when loading the camera, as the door would misalign if given half a chance.

eBay Austrian seller “leica-by-boris” has a Zi Jin Shan for sale, but it ain’t cheap: https://www.ebay.com/sch/i.html?_from=R40&_trksid=p2380057.m570.l1313&_nkw=zi+jin+shan&_sacat=625

Say £7,500! (Plus postage)

Great review, and as usual it triggered my gas. Unfortunately on eBay I discovered that the price of the DF series is ridiculously high, entering rollei/mamiya tlr territory. Definitely something I would pick up at $50, but not $600.

Wow! That’s definitely not worth it! Setup something on a watch list and wait for one to be listed at a more reasonable price. That is how I usually get cameras for these reviews. Sometimes I have a camera on my watch list for a year or two before one finally shows up at the right price. Patience is definitely the key to getting a bargain!

An interesting camera, Mike, and with a lens that doesn’t embarrass it. But certainly one for collector interest going by the prices on ebay. Looks like the horse has bolted to be able to pick one up for a reasonable amount.

Actually, the part of you review that caught my attention was the film, Shanghai GP3, and which really showed how sharp the lens was, and it had clean grain. Googling it, I found a number of sellers here in the UK with fresh stock but on price it can’t compete with the price we can get Ilford FP4 for here in the UK. The price is much closer to that of Kodak film. But, and here comes the really interesting bit, it is being offered in 35mm, 127, 620, 120 and 220!

A very interesting review, as always! It is a delight to read your page, and much is learned from it.

As a modest form of thanks, I will give you this.

The decision of using LTM / L39 mounts outside its “normal” 18mm flange distance is puzzling at first glance, but not absurd. And this is HARDLY the only camera to do so: The first model Zenit reflex camera had an L39 mount (with a reflex flange distance, obviously) for its 50mm lens. So did the tiny, wonderful Chaika (Small viewfinder half-frame) in an abortive “short-but-not-short-enough” flange distance for its 30mm.

Did you figured out already? It made me chuckle when I did!

L39 is/was also the de-facto standard… for enlarger lenses! Chinese and eastern-european photographers were much too poor to afford a separate enlarging lens, and used the one already present in their cameras.

This is especially useful on the chaika, since enlarger lenses shorter than 50mm are quite hard to come by.

Keep up the great work!

A fan.

Just found one of these for a great deal. I’ve only shot two photos but I already love how it fits in my hands. I hope I don’t have a lemon. Thanks for helping me better understand this camera.

Glad you found the review helpful and congrats on the pickup! If you ever get any cool macro shots using any other M39 lenses, please let me know!

这个相机在中国 80年代全新的 100RMB 大约是当时普通人3个月工资 现在在中国二手市场库存全新的 大概500-900RMB 我去年也买了一台花了980rmb 大概合140美元 用L39螺口是因为 它和放大机放大头的螺口一样这样可以省下放大镜头的钱。当时的中国很穷,这样能省放大头的钱。

Translation:

This camera was brand new in China in the 1980s at 100RMB, which was about 3 months’ wages for ordinary people at that time, and now the new ones in stock in the second-hand market in China are about 500-900RMB. I also bought a camera last year and spent 980rmb, which is about 140 US dollars. The L39 screw is used because It is the same as the screw on the magnifying head of the magnifying machine, which can save money on the magnifying lens. China was very poor at that time, so it could save a lot of money.