This is a Super Deluxe 1.7 rangefinder camera, produced by Mamiya Optical Co. starting in 1964. The Mamiya Super Deluxe was a premium 35mm rangefinder and was Mamiya’s first camera to feature a CdS exposure meter. Although the Super Deluxe has a non-removable lens, there were three versions available of this camera with three different lenses. This one with a Mamiya-Sekor f/1.7, and ones with a Mamiya-Sekor f/1.5 lens, and a Mamiya-Kominar f/2 lens. The Mamiya Super Deluxe competed with a large number of very similar Japanese 35mm rangefinders and struggled to stand out, which resulted in a rather short life span for this series. Compared to similar models by Minolta, Canon, Yashica, Olympus, and Konica, the Mamiya Super Deluxe is harder to find today.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 48mm f/1.7 Mamiya-Sekor coated 6-elements in 4-groups

Focus: 3.3 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder, Automatic Parallax Correction

Shutter: Copal SVE Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: Coupled CdS Cell w/ top plate and viewfinder match needle

Battery: 1.35v PX625 Mercury Battery

Flash Mount: Cold shoe and M and X Flash Sync

Other Features: Self-Timer, Automatic Resetting Exposure Counter

Weight: 758 grams

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/mamiya_pdf/mamiya_sekor_de_luxe.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Mamiya Super Deluxe is a pretty typical early to mid 1960s Japanese rangefinder. Featuring a large, mostly metal body, with squared off edges, a fast f/1.7 lens, a coupled rangefinder, and a coupled CdS meter with match needle capability, the Super Deluxe gives you everything you’d ever need to make really nice pictures. If you are new to shooting film or rangefinders, you could do a LOT worse than this camera. For me, the Super Deluxe offers nothing that a dozen other competing models from the same era offered. It works exactly like other offerings from Yashica, Minolta, Konica, Canon, and others, making it difficult to get excited about. This is a fine camera that does exactly what it should, and it does it well, but for the collector looking for something different, this isn’t it. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 20% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 8.4 | ||||||

History

Mamiya was originally founded in 1940 by inventor Mamiya Seiichi and investor Sugawara Tsunejirō as Mamiya Kōki Seisakusho (Mamiya Optical Works). The company’s first camera was the Mamiya Six, a folding camera that shot 6cm x 6cm negatives on 120 roll film. Mamiya saw immediate success upon the release of it’s camera, and was one of the few optical companies that continued to grow during World War II. By early 1944, the company had grown to 150 employees and had expanded to a second facility on the grounds of Tokyo University to build lenses.

In October 1945, Mamiya was the first Japanese optical company to receive an order to resume production by the office of General Douglas MacArthur during the Allied occupation of Japan following World War II. A few months later in January 1946, Mamiya had resumed full scale production of the Mamiya Six at a new facility in Tokyo.

Over the course of the next 8 years, the Mamiya Six would be upgraded several different times, adding features like a rangefinder, dual 6×6 and 6×4.5 format, better shutters, and better lenses. In 1948, Mamiya would expand their product line to include a 6cm x 6cm TLR called the Mamiyaflex and a fixed lens 35mm rangefinder and a year later, a 16mm subminiature camera called the Mamiya 16.

Mamiya’s rangefinder lineup started with the Mamiya 35 which went through three revisions, referred to today as the 35-I, 35-II, and 35-III. The first two models looked very similar from the outside with the most significant difference being the first model adopted a back focus feature first used on the Mamiya Six in which changing focus was not done by moving the lens, rather the film plane which would move forward and aft from minimum to infinity focus. This proved to be difficult and expensive to produce so later models abandoned it.

The Model III was released in 1957 and was based on the earlier models, but added several significant updates including a focusing helix, film advance lever instead of a knob, new Seikosha MXL shutter, and EV coupling. These additional features increased the weight of the camera by 10% and also increased it’s size in every dimension.

Over the course of the next couple of years, Mamiya would continue to release new 35mm rangefinder models like the Elca, Crown, Ruby, EE Merit, Auto-Metra, and Auto-Deluxe, most sharing similar feature sets, adding features like selenium meters, different combinations of shutters, and lenses, and modifying the cosmetics a bit. One model, in particular, the Mamiya Magazine added a very unique ability to separate the entire film chamber from the rest of the camera, allowing a photographer to swap rolls of film mid roll, without removing the film. This feature worked similarly to the Kodak Ektra from the 1940s.

In August 1964, with a majority of it’s competitors releasing models with new Cadmium Sulfide coupled meters and some level of automation, Mamiya released the Mamiya Super Deluxe. Although a fixed lens camera, the Super Deluxe was available with three different lenses. Initially, it was just the Mamiya-Sekor 48mm f/1.7 or a Mamiya Kominar f/2 lens, but in November, 1964, ones with a faster f/1.5 Mamiya-Sekor was available. For a short while after it’s release the f/1.5 equipped Mamiya Super Deluxe had the fastest lens ever offered on a fixed lens camera. A year later, Yashica would top it with the f/1.4 equipped Yashica Lynx-14.

From a glance, the three different versions of the Mamiya Super Deluxe look the same excepting the lens, but there were other differences. They are:

- The f/1.5 and f/1.7 models had the same shutter with MX flash synchronization, but the f/2 version lacked selectable MX sync.

- Both the f/1.5 and f/2 models have EV couplings, linking the shutter speed with aperture rings, but on the f/1.7 they are uncoupled with no EV scale.

- Each of the three models had a different design of the ASA film speed selector, with the f/2 model having a different sequence.

All three models would have other cosmetic changes throughout their production spans with earlier models having the name Mamiya in gold letters to the right of the viewfinder, with later models saying Mamiya/Sekor on the bottom. Changes to the typeface of “Super Deluxe” have been observed too.

Exactly how long the Mamiya Super Deluxes were produced is not known, but my guess is for not very long. A couple of factors in that while they were well built cameras, apart from the availability of the f/1.5 lens, nothing else stood out about these models that you couldn’t get from a half dozen other Japanese companies. Not to mention, the rising popularity of SLRs, along with more and more affordable options decreased the pool of people looking to buy a rangefinder each year.

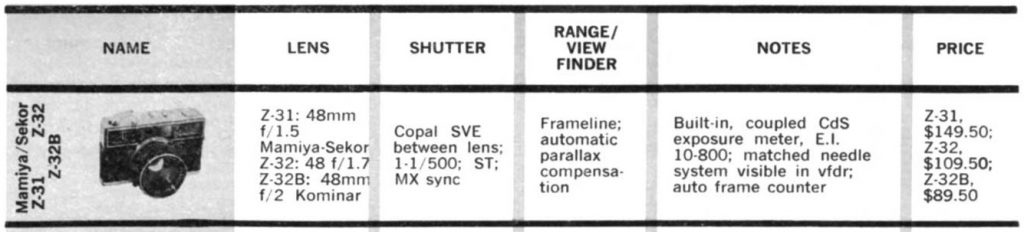

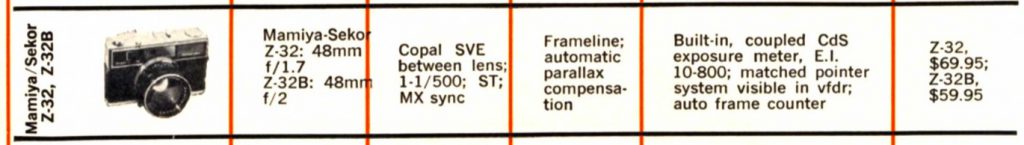

Perhaps the best sign of a quick exit come from both of Modern Photography’s December 1964 and 1965 year end price guides shown above in which all three Mamiya models are shown available with prices from $149.50 for the f/1.5 and $89.50 for the f/2, but only a year later, the f/1.5 is missing, with the other two showing dramatic price drops to $69.95 and $59.95. The only explanation of such a large drop in price would be that they didn’t sell well.

Another thing that’s not clear is why Modern refers to the Super Deluxe models as Z-31, Z-32. and Z-32b in both the 1964 and 65 round ups. I would have maybe guessed if these were pre-production names that were provided to the magazines before an official name was chosen and the 1964 issue was finalized before changes could be made, but since the names appear in the next year’s edition, more than a year after the camera’s release is strange.

Whatever the reason, we know for sure the cameras were available both years, possibly into 1966, but at steep discounts barely a year after they first made their debut.

Mamiya would continue producing rangefinders beyond the Super Deluxe, but as each new model was released, they became more and more ordinary, lacking any identity beyond a “good but unremarkable Japanese rangefinder”.

Today, 1960s Japanese rangefinders are still a very popular option for those looking to get back into film photography. Their rugged build quality, fully mechanical operation, excellent lenses, and ease of use make for a compelling formula. The Mamiya Super Deluxe sticks to that formula with very little deviation, making for a predictable, yet unremarkable option. There is nothing wrong with owning or collecting these cameras, but for someone looking for something unique or different from similar options by other Japanese makers will likely be disappointed.

My Thoughts

In the history of the Japanese camera industry, there was a brief moment in the mid 1960s where a large number of camera makers all had the same idea of how a 35mm rangefinder should look. Companies like Konica, Minolta. Yashica, Olympus, and Mamiya all produced large bodied 35mm rangefinder cameras with metal bodies and sharp corners.

All these cameras would have leaf shutters, a body or lens mounted Cadmium Sulfide exposure meter with match needle display, a coupled rangefinder inside of a pretty bright rectangular viewfinder, and would have some type of sub f/2 lens capable of making pretty good photographs.

I could probably end this review right here and you’d have most of what you need to know about the Mamiya Super Deluxe as apart from some Olympus-like black trim on the front of the camera, doesn’t stray too far from the formula outlined above. That said, to say the Mamiya Super Deluxe is a camera you shouldn’t ever consider would do it a disservice, so here we go.

Holding the Mamiya Super Deluxe, it is clear that whatever creativity might be lacking from it’s design, that in no way shape or form detracts from it’s quality. This is a stout and heavy camera, that aside from a few pieces of plastic trim, is a solid and heavy piece of metal. What little electronics are used for the meter, the rest of the camera operates on gears, levers, and springs. With it’s many right angle corners and 758 gram weight, this is definitely not a camera you’d want to drop on your bare foot.

The top plate’s design is clean and straight to the point. On the left is a pop-up folding rewind knob, then the accessory shoe, match needle read out, film advance lever, cable threaded shutter release, and automatic resetting exposure counter. The exposure counter counts up the number of exposures made. The film advance lever has a relatively short throw that I would estimate requires only a 140 degree motion. You must make it in a single motion however, as several shorter strokes are not permitted.

The base of the camera has the round opening for the PX625 mercury battery that powers the meter. In the center is a 1/4″ threaded tripod socket. and off to the side is the rewind release button. A nice little touch is that the rewind button has a small red dot that spins as you advance the film, allowing you to see if film is correctly transporting onto the take up spool.

The camera’s sides have little to see other than the front angled tripod lugs and on the bottom of the left side, the release for the film door. Simply pull down on the little catch and the door pops open.

Around back, there is the rectangular eyepiece opening for the viewfinder. To the right of the viewfinder is a round dial for turning the CdS meter on and off. This is actually a pretty nice touch as many cameras of this era did not have a power switch for the meter, requiring you to use a lens cap or some other means to prevent the meter from draining your battery.

The right hinged door reveals the Mamiya Super Deluxe’s film compartment. Film transports from left to right onto a fixed and double slotted take up spool. The film pressure plate is large and covered in small divots to reduce friction as film passes over it. A small metal roller on one side helps maintain film flatness as it passes over the exposure counter shaft. Like most cameras of it’s day, the Mamiya Super Deluxe uses foam light seals which should be replaced before shooting.

Exposure and focus controls on the Mamiya Super Deluxe is much like that of many other Japanese leaf shutter rangefinders, where everything is controlled by rings around the shutter. The focus ring is closest to the body of the lens and has a single tab sticking out of the side to make it easier to locate. The motion from minimum to infinity focus is quite short, which I estimate to be about 30 degrees, but this was the norm by the 1960s as coupled rangefinder systems valued speed over precision.

Earlier in this article, I detailed some differences between models of this camera with the f/1.7 lens compared to the f/1.5 and f/2 versions, which is this version is the only one without a coupled EV scale, and if you’ve been reading this site for more than a few minutes, you’ll know I do not like coupled scales like this, so while the f/1.5 Super Deluxe might be the most desirable, as a user the f/1.7 version is the best as you are free to choose any combination of shutter speeds or f/stops without having to deal with them being linked together.

Also visible in the previous image above is a small lever with a red dot on it which activates the self timer. As is the case with any camera with a mechanical self timer, you should avoid using it unless you are absolutely certain it works, or if the camera had a recent servicing as a stuck self timer can jam up the entire shutter.

The Mamiya Super Deluxe’s viewfinder is large and bright, with projected frame lines with automatic parallax correction and a rectangular rangefinder patch in the center. As you focus the lens towards minimum focus, the frame lines slowly move down and to the right to compensate for parallax error. Seeing the entire image, even while wearing prescription glasses was not a problem at all. Above the frame lines is a horizontal match needle scale for the exposure meter. This scale duplicates the one on the camera’s top plate and shows under exposure to the left and over to the right.

Although the blue and pinkish contrast of the main viewfinder and frame lines/rangefinder patch was easy enough to see, this camera, like many from it’s era suffers from some mild haze which reduces contrast. This is something that can sometimes be resolved by removing the top plate and cleaning the viewfinder glass, but in many cases, it is a result of the beamsplitter either hazing up or desilvering, which both cases require a replacement beamsplitter.

As has been a theme of this entire review, the Mamiya Super Deluxe is a really nice camera with a lot of good things going for it. It has a great lens, a capable shutter, and very user friendly ergonomics. It has a couple of nice touches such as automatic parallax correction in the viewfinder, a relatively short throw for the film advance, and lacks any sort of coupling between the shutter speed and f/stops, but so did many other cameras from this period. Spec for spec, there’s not much to differentiate it from it’s competition, but perhaps we’ll see a difference when shooting some film in it…

My Results

With depleting supplies of Fuji 200 and summer light, I took the Mamiya Super Deluxe with me on a trip to a pumpkin farm in late October hopefully to get some good fall foliage shots. The Fuji 200 was expired by about 3 years, but it’s film I’ve shot a number of times, so I pretty much knew what to expect and I thought it would pair well with the Mamiya-Sekor coated 6-element lens.

Sadly, it would seem that my trusty supply of Fuji 200 that I picked up when Walmart stopped selling it in 2017 seems to reached it’s end of life as the images above came out a bit muted with a noticeable cyan shift. While I can blame the film for most of the color quality of the images above, perhaps I shouldn’t be so forgiving on the Mamiya-Sekor lens as it has a noticeable yellow tint that likely affected the colors too.

Colors aside, the sharpness and coverage of the lens is about what I expected from a mid 1960s 6-element prime lens made by a major Japanese manufacturer. Last year, I shot some film through the Argus SLR, which is really a rebranded Mamiya from the same era, and got similar looking images, which is to say, really nice, but not remarkable. Sharpness is even across the frame with only the slightest hits of softness near the corners. I don’t usually shoot lenses wide open, but based on previous experiences, I am quite certain they would show more softness at f/1.7. No vignetting is visible on images with detail in the corners, but if I stare at images with the sky long enough, I do see some darkness creeping in at the corners.

I generally liked the Mamiya Super Deluxe and can see how it would appeal to a consumer looking for a solid, full bodied, mostly metal mechanical Japanese rangefinder. It does everything it should, the way it should, delivering the results it should.

Therein lies a feeling of ambivalence that I’ve had with this camera since the first moment I picked it up. While this camera has the specs that it should, and doesn’t do anything fundamentally wrong, I struggled to ever get excited to use it. This includes the time before, during, and after I shot my one and only roll through it. Normally, when I shoot a camera that doesn’t excite me after a first roll, I like to give it a second chance with another roll before making any conclusions in it, but in the four months since I last shot this camera, I’ve handled it a number of times, trying to will myself into getting excited about it, and I just couldn’t.

Perhaps I have unintentionally discovered the reason this camera was in production for such a short time and why it had such a significant price reduction within one year of it’s release, that my feeling of “meh” was shared by those who handled it back then.

Disclaimer time…the Mamiya Super Deluxe is definitely not a bad camera. I think my problem is that I’ve simply shot too many similar cameras that this style of “Japanese 35mm rangefinder with sub f/2 lens” does not excite me any more. If you are new to film photography, or don’t have a lot of experience with Japanese rangefinders and one of these comes your way at a price you are happy with, I absolutely think you should give it a try as I’m sure you’ll like it. But if you’re like me, and have shot countless similar cameras over the years, don’t expect to find anything new or unique about the camera or the experience.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Mamiya_35_Super_Deluxe

http://www.herron.50megs.com/rangefinder.htm

http://www.collection-appareils.fr/x/html/page_standard.php?id_appareil=12636

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MHJZzvGN9lw (in Spanish)

Great article on the Mamiya Super Deluxe. From factory records, here is some production info:

Super Deluxe with F/2 lens produced from March 1964 to July 1965, 6000 produced

Super Deluxe with F/1.7 lens produced from June 1964 to September 1965, 13,000 produced

Super Deluxe with F/1.5 lens produced from September 1964 to July 1965, 16,000 produced

Wow, this is great info Bill! I find it interesting that they made more of the f/1.5s as they were the most expensive and the hardest to find today. I guess though the 1.5 was the most desirable though, so perhaps they were anticipating higher demand. Thanks for sharing!

Also, there were three different versions of top covers on the various models: one version has “Mamiya” engraved on top, another has a sticker that says “Mamiya/Sekor” over the “Mamiya” engraving and the last version has “Mamiya/Sekor” engraved on the top cover. Your copy, which has “Mamiya/Sekor” engraved, is the least common in my experience. I think this was done for different markets in the world.

“Uh, Houston, we have a problem.” Your description states that the Mamiya Super Deluxe 1.7 featured a CdS light meter. But the Exposure Meter is a “Coupled Selenium Cell w/ top plate and viewfinder match needle.” That is followed by Battery: “1.35V PX625 Mercury Battery.” As I recall, the Selenium cell on my Olde Sekonic L-28C light meter didn’t require a battery. My later Sekonic L-98 Micro-Leader, which used a CdS cell required Ye Olde PX13 Mercury battery to measure “available darkness.” Sorry, but watching old episodes of “Columbo” on Sundance TV has me seeing discrepancies and asking “just one more question.”;)

Aaah, you got me, Patrick! It seems that my ambivalence towards this camera extended into my proofreading before I published it. This camera most certainly has a CdS meter powered by a PX625 cell, with match needle on the top plate and in the viewfinder. I have made the correction. Good catch!

Your ennui is understandable- I would say there are scores of similar Japanese RF cameras from that era- most of them pretty good.

Great, informative article, thank you! While your reasons not loving this camera are well explained and understandable, perhaps interestingly the Super Deluxe is one of my favourite and often used RF in my collection – albeit with the 1.5 lens which I believe the special sauce in the package. The rest of the camera is – as you said – well made and reliable without any quirks. The flip side is that it gets out of the way and shooting is easy, while the 1.5 has a lot of quirks and surprises and tons of character. If not for collection value but as a shooter to me this is a winning combo. One small note, my 1.5 doesn’t seem to have coupled EV system which is my preference also.

Glad to hear the 1.5 version has that special extra that elevates this camera to be a regular shooter for you. That is interesting that your 1.5 doesn’t have the coupled EV system, as I got that information straight out of the manual. Sounds like you either have a very early or very late version. In any case, thanks for the feedback and keep shooting!