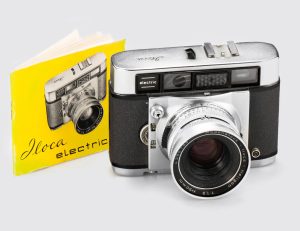

This is a Graflex Graphic 35 Electric, an electrically powered motor driven interchangeable lens 35mm rangefinder made in Hamburg, West Germany by Iloca for Graflex, Inc of Rochester, NY in 1959. The Graphic 35 Electric is a name variant of the Iloca Electric, which has all of the same features. Both cameras were the first ever designed for AA “pen-light” batteries and used an internal electric motor drive that not only advanced the film, but also set and fired the shutter. Unlike some other early electric drive cameras, the Graphic 35 Electric has no manual override, meaning when the batteries die, or the electronics fail, the camera will no longer work. In addition to the electric motor drive, the camera is well featured with an interchangeable DKL lens mount, coupled rangefinder, and coupled selenium exposure meter. Like all cutting edge cameras, the camera was expensive, sold poorly, and was in production for a very short amount of time.

This is a Graflex Graphic 35 Electric, an electrically powered motor driven interchangeable lens 35mm rangefinder made in Hamburg, West Germany by Iloca for Graflex, Inc of Rochester, NY in 1959. The Graphic 35 Electric is a name variant of the Iloca Electric, which has all of the same features. Both cameras were the first ever designed for AA “pen-light” batteries and used an internal electric motor drive that not only advanced the film, but also set and fired the shutter. Unlike some other early electric drive cameras, the Graphic 35 Electric has no manual override, meaning when the batteries die, or the electronics fail, the camera will no longer work. In addition to the electric motor drive, the camera is well featured with an interchangeable DKL lens mount, coupled rangefinder, and coupled selenium exposure meter. Like all cutting edge cameras, the camera was expensive, sold poorly, and was in production for a very short amount of time.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 50mm f/2.8 Iloca-Culminar coated 4-elements in 3-groups

Lens Mount: DKL Bayonet Mount

Focus: 3 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder w/ 50mm and 135mm Projected Frame Lines, Match Needle Readout, Automatic Parallax Correction

Shutter: Synchro Compur Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: Coupled Selenium Cell w/ top plate and viewfinder match needle

Battery: (2x) 1.5v AA Zinc-Carbon or Alkaline Battery

Flash Mount: Cold shoe and M and X Flash Sync

Other Features: Self-Timer, Motor Drive

Weight: 862 grams, 754 grams (body only)

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/pdf_files/graphic_35_electric.pdf

History

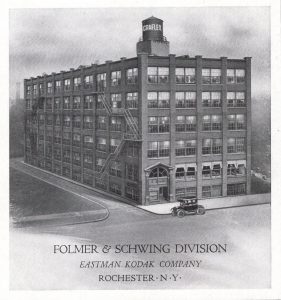

Graflex is one of the most storied camera brands of all time. Originally formed in 1887 as the Folmer and Schwing Manufacturing Company by William F. Folmer and William E. Schwing, the company produced a variety of gas lighting fixtures, lamps, bicycles, and starting in 1898, cameras. Their Graflex Reflex series came with focal plane shutters and proved to be popular and competed with the likes of Anthony & Scovill Companies lines of similar cameras.

Between 1905 and 1906 the company was acquired by George Eastman and became the Folmer & Schwing division of Eastman Kodak. A variety of new twin lens, stereoscopic, sheet film, and roll film cameras were released by the company over the next couple of years.

In 1912, the first Speed Graphic press camera would be released that would be the foundation for a successful line of press cameras that would stay in production until the early 1970s. The Speed Graphic would launch several other models, some with focal plane shutters and others with leaf shutters.

The rapid success of the Folmer & Schwing division of Kodak was so successful that in 1926 the company was found by the US government to be in violation of the Sherman Anti-Trust Act and two years later, was forced to split off it’s Graflex division into a separate company which would be known as the Folmer Graflex Corp of Rochester, NY.

During World War II, Folmer Graflex would produce a variety of aerial and military use cameras that were used by Allied forces. Their press cameras remained popular back home and continued to sell well in the years that would follow. Perhaps in an effort to clearly identify themselves as the maker of Graflex cameras, in 1945, the company would once again change it’s name to Graflex Inc.

It was during these years that Graflex cameras saw their greatest success. Press photographers regularly used Speed, Crown, and Century Graphics almost exclusively. Although exact production numbers were not kept, efforts to analyze production numbers by serial numbers suggest that total production extended into the several hundreds of thousands.

In the years after World War II, the history of Graflex started to get a little strange as the company put their name on a variety of cameras produced by other companies they acquired and others they licensed their name to.

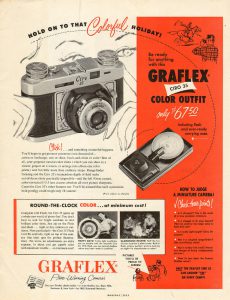

The first such model was the Graflex Ciro 35 in 1949, which was based off earlier Perfex cameras produced by the Candid Camera Corporation of Chicago. In 1955, the Ciro 35 would be heavily redesigned and turned into a new camera called the Graflex Graphic 35 that was built by Graflex, but used German lenses and shutters.

In 1951, Graflex would produce another of Ciro’s cameras, their twin lens reflex camera, the Ciro-Flex, first still using the Ciro-Flex name, but starting in 1953, rebadged as the Graflex 22. A total of three different models would be released called the 22-200, 22-400, and 22-400F which matched up feature for feature with the original Ciro-Flex Models D, E, and F.

Once again 1957, Graflex would tap the expertise of another camera company, this time, the Japanese company Kowa, whose Kallo 35 series of rangefinders and scale focus cameras had been in production. For Graflex, Kowa would rebadge their Kowa 35 rangefinder and sell it as the Graflex Century 35, a capable midlevel 35mm rangefinder with quality Japanese optics.

Graflex would continue their relationship with Kowa in 1961 with the release of the strangely ambitious, Graflex Graphic 35 Jet, a robust 35mm rangefinder with a rapid motor drive powered by a small bottle of compressed carbon dioxide gas. The Graphic 35 Jet is the only camera ever built to be powered by compressed CO2.

Although the camera technically worked, it was plagued with reliability problems of it’s O-rings, and with a very high price tag and a technology that was a tough sell to customers, it sold very poorly. So poorly in fact, that shortly after it’s release, unsold inventory was sent back to the factory where Graflex “neutered” the cameras, removing the jet propulsion features, so that it could be resold as a manual film advance camera at a reduced cost.

In between Graflex’s first and last Kowa partnership, in 1959 they reached an agreement with yet another company, the German camera maker Iloca from Hamburg, West Germany.

Iloca Camera Werk was a relatively new company, founded by A. Walter Illing in 1947. Iloca originally produced precision parts for other companies, but around 1950 started making their own cameras. Competing in a crowded market, Iloca found success partnering with a variety of other, mostly American companies, producing cameras under contract for them, A variety of Tower cameras were produced for Sears, Roebuck, & Company, but other models like the Argus V-100, David White Stereo Realist, and Montgomery Wards Photrix Stereo were also produced.

One additional camera, which Iloca called the Iloca Electric, was introduced in 1959 that would end up being the company’s most ambitious camera to date. Featuring a coupled rangefinder, coupled selenium exposure meter, and an interchangeable Deckel lens mount, the Iloca Electric’s signature feature was it’s battery powered electric motor drive. Like electrically driven cameras from decades later, the Iloca Electric relied on two AA “penlight” batteries. Batteries of this era were zinc-carbon dry cells, but later advancements in alkaline battery technology means that modern alkaline AA batteries would work as well.

The electric motor inside of the camera handled film advance and all shutter operation. A selenium meter on top of the camera was coupled to the shutter, allowing for match needle exposure calculation, but the camera did not have any auto exposure capabilities. Still, the idea of an electrically powered camera was quite advanced for it’s day.

Graflex made an agreement with Iloca to build a name variant of the Iloca Electric as the Graflex Graphic 35 Electric. Other than the name, the two cameras were identical, but nevertheless, allowed Graflex to promote themselves as the first American company to have an electrically powered 35mm camera.

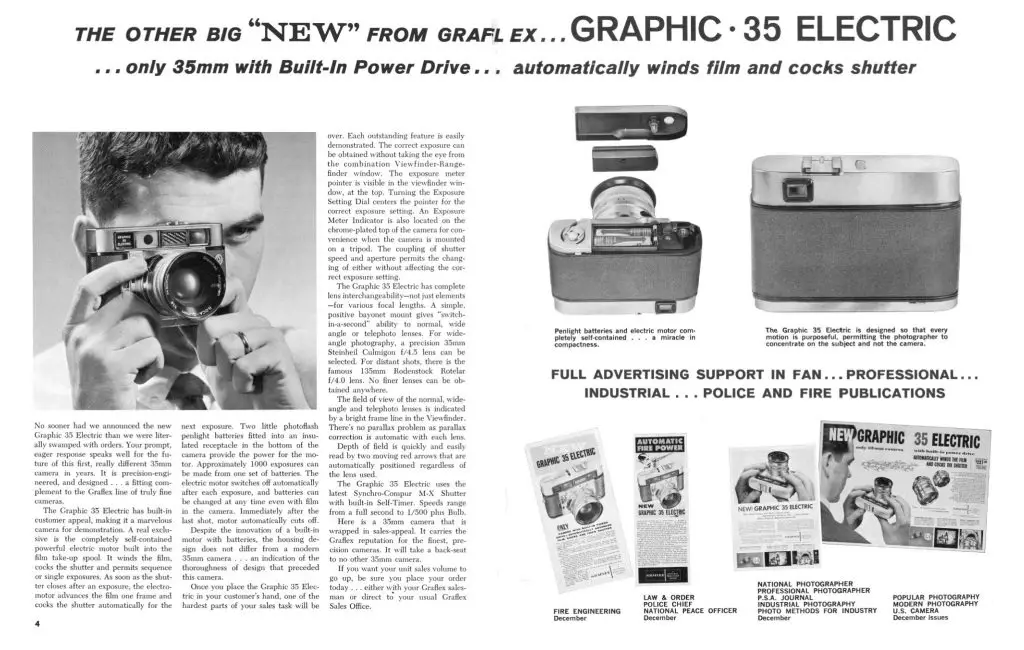

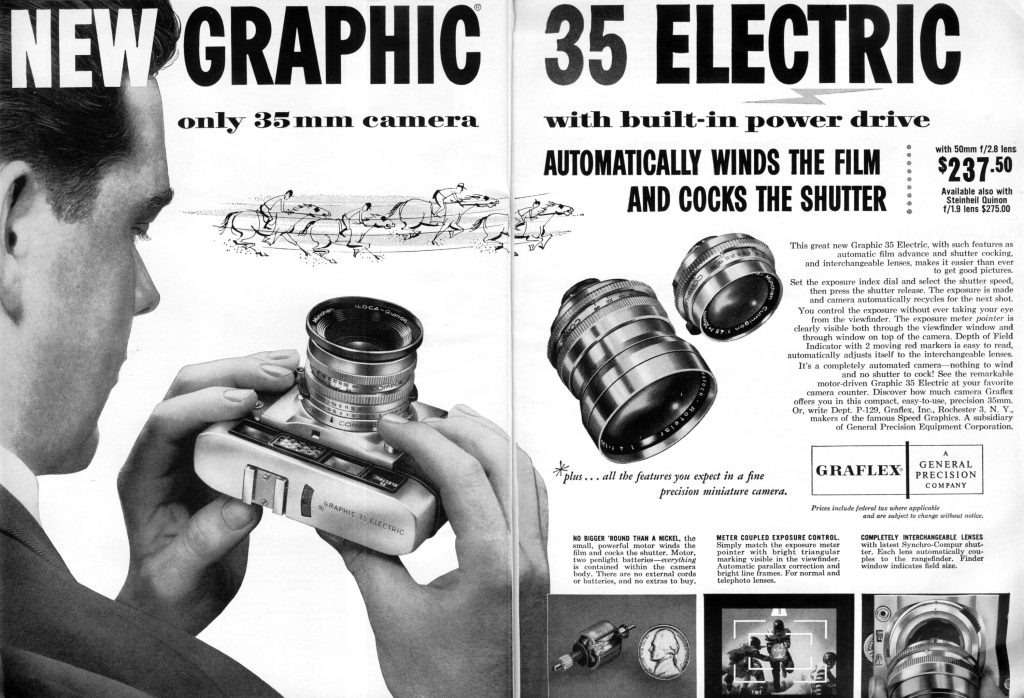

I found no record of how the Iloca camera was marketed or sold in Germany, but in the United States, as the short promotional article above suggests, the Graflex was advertised in a variety of publications. The following ad appeared in the December 1959 issue of Popular Photography.

In March 1960, the camera was tested by Herbert Keppler in his monthly Modern Tests columns in Modern Photography Magazine. Keppler wastes little time getting to the electric motor drive, humorously suggesting that atomic powered cameras might still be a ways off, but that we are doing alright with electric ones. He quickly points out that the rapid fire speed of the Graflex Graphic 35 Electric isn’t all that impressive, only able to fire off 3 shots in 5 seconds, which compared to a trigger wind camera (he’s almost certainly referring to a Leica with the Leicavit accessory) can manage 1 shot per second.

He does comment however, that the greatest benefit of the Graphic 35 Electric isn’t it’s top speed, but rather it’s combination of speed and smoothness. Using a trigger wind camera of the same era, although you can physically fire the shutter quickly, doing so requires quite a bit of motion from your hands, which caused a great deal of body shake, meaning that the faster you shoot those cameras, the more likely you are to blur your images. With the Graphic 35 Electric, the camera is remarkably steady, allowing you to confidently fire off a sequence of images that will show no sign of body shake.

The article continues pointing out the camera’s interchangeable Deckel mount allows for flexibility at all the commonly used focal lengths and that the viewfinder is good enough, although that seeing the edges with the 35mm lens would be quite difficult while wearing glasses.

In March 1960, the Graflex Graphic 35 Electric had a retail price of $275 when equipped with the 50mm f/1.9 Iloca-Quinon lens which when adjusted for inflation, compares to $2700 today. This would have been a very ambitious price, especially for a model sold by a company not known for premium products with a feature that many people probably didn’t think they needed.

As you might imagine, the camera sold poorly and was not promoted for very long. In fact, other than the March 1960 review from Modern Photography above, I could not find any advertisements for the camera past that, suggesting the camera was likely not on anyone’s radar even while that issue was in the newsstands.

The relative failure of the CO2 powered Graflex Graphic 35 Jet a year later further suggests that Graflex was grasping at straws in this era desperately trying anything they could to be different. Sadly, it resulted in the end of the company’s 35mm effort, with their Graflex press cameras slowly falling out of popularity as well. Graflex would continue to stumble through the rest of the 1960s before being acquired in 1968 by the Singer Corporation who continued Graflex camera production for another couple of years before completely dissolving the company.

Today, there’s certainly a lot of collectors who seek out historically significant interchangeable lens German rangefinders, but I’m not so certain many people are looking for this particular historically significant interchangeable lens German rangefinder. That’s not to say the Iloca built Graflex Graphic 35 Electric isn’t worth your time, its just that they’re so incredibly difficult to find, and that they were both sold and made by companies whose cameras rarely excite the dedicated collector.

If however, you’re interested in a solidly made camera, with a long list of features, one of which was a historic first, then perhaps one of these cameras are for you, if anything other than to adapt the DKL lenses to some other camera. What the Graflex Graphic 35 Electric lacks in collector desirability, it more than makes up for in shelf appeal!

My Thoughts

“Hey dude, I got a box of stuff for you…”

“Oh wow man, that’s cool, I’ll give you my address.”

“No way, it’s too heavy, we have to meet up…”

“Okay, when do you want to do it?”

…months pass…

“Hey, do you still have that stuff you wanted to give me?”

“Yeah, I’ll be in the city tomorrow, let’s meet somewhere.”

“How about I send my wife to pick it up?”

“Okay, that works for me.”

The above is an actual conversation (paraphrased for brevity) of what went down between me and Johnny Sisson when he was purging himself of boxes of cameras that he no longer wanted. In that box were half a dozen Exaktas, a couple Pentaxes, some Argus C3s, a Zenit or two, and this Graflex Graphic 35 Electric. Being the only camera I had never heard of before, I was instantly interested in the possibilities of what I would later discover to be the first camera electrically powered by regular AA batteries.

The first thing I noticed when I picked up the Graflex is how heavy it is. For a 35mm rangefinder, at 862 grams, it is well within SLR territory. This particular camera had mounted the 50mm f/2.8 Iloca-Culminar, which is a relatively light weight lens. Had I mounted the 50mm f/1.9 Iloca-Quinon lens that was advertised with the camera when it was new, it would have likely tipped the scales at around 1000 grams which is heavier even than many medium format twin lens reflex cameras.

Up top, the uncluttered top plate hints at the camera’s electronic features as there’s no need for things such as a film advance lever. All that’s here is the accessory cold shoe and match needle readout from the coupled selenium exposure meter,

Flip the camera over and we see the fold out rewind knob on the left, the cover for the battery compartment, a coin operated screw for removing the battery compartment, and the offset 1/4″ tripod socket. While I would normally lament the location of a tripod socket on the side of such a heavy camera, the need for the battery compartment is understandable.

Opening the battery compartment with a coin is a curious decision but I guess with such little experience making electronic cameras, the designers at Iloca wanted it to be secure. With the metal cover off, underneath we see….another cover!

Unlike the outer cover, an inner black plastic cover has a simple clip to remove, revealing the two slots for the AA cells. It’s worth noting that in the era this camera was made, AA cells were usually paper wrapped zinc-carbon dry cells that were ever so slightly thicker than modern day AA batteries. A modern alkaline cell will still work, but it will be a tad loose in the compartment. Each of the two sides of the battery compartment you’ll see large white plus signs to help with polarity, which probably makes sense as this style of battery was likely still new for many people.

The sides of the Graflex are rather spartan, not even featuring strap lugs, which means that in order to attach a neck strap, you’d either have to use the original ever ready case, or some kind of tripod socket adapter. From the camera’s left side, you get a look at the front mounted shutter release, ASA film speed dial, and green lever for selecting between M and X flash sync and the V position for the self timer.

Around back there’s very little to see other than the rectangular eyepiece for the viewfinder and a very small metal lever in the lower right corner which is used both to release the rewind lever on the bottom of the camera and also unlock the film compartment door.

As with other Iloca produced cameras like the Argus V-100, opening the film compartment is a mystery for the first time user. There is no latch on the side or obvious lever to pull up on to release the door. Sliding the tiny lever on the back of the camera to pop up the rewind lever at first doesn’t appear to do anything, as tugging up on the lever after you’ve unlocked it does nothing as well. It’s not until after releasing the rewind lever, that you have to keep holding that tiny release lever while giving the now loose rewind lever a second tug, that the door will release. Although not difficult to do, it is not at all obvious and likely has confounded more than a few first time, and even repeat users of this camera.

As with most 35mm cameras with the film rewind lever on the bottom, film transport is reversed, going from right to left. The take up spool is fixed and single slotted, but is also much larger than the typical 35mm camera spool, more closely resembling a drum.

Loading in a new roll of film requires you to insert the leader into the vertical slot in the take up drum and manually rotate it one revolution so that the film is properly secured. A red dot above the take up drum seems to indicate the position you are supposed to line up the slot with, but there is no mention of it’s purpose in the camera’s manual. The electronic film transport is disengaged when the back is removed, so you can rotate the drum freely.

After attaching the leader and inserting the cassette into the supply side, there is one more step you need to do before attaching the back, which is to reset the exposure counter. Once again, like other Iloca cameras, resetting the exposure counter can only be done with the back removed. If you forget to do this step, you’ll need to take it off again. A large toothed wheel above the film gate manually rotates the exposure counter. This wheel freely rotates in any direction so you can go any way you like. The exposure counter is subtractive, showing how many exposures remain on a roll, so when loading in a new roll, you must set the counter to two above however many exposures are in your cassette. For a 36 exposure roll, set it to two small arrows beyond the 36th number. For a 20 exposure cassette, set it to a red number 22. Back then, 24 exposure cassettes didn’t exist, so the number 26 isn’t in red, but if that’s what you were using, you’d set it to 26.

One final tip is that the back of the camera is nearly symmetrical, but has a small roller on one side preventing you from putting it on the wrong way. If you encounter resistance trying to attach the back, you probably have it upside down.

Back up top, looking down upon the shutter and lens, first we see a small square window above the lens mount which is the exposure counter. A curious, but somewhat convenient location for this counter, as mentioned earlier, it is subtractive, showing how many exposures remain. I’ll take this time to say it again, remember to reset this counter before attaching the back of the camera after loading in a new roll of film!

The Graflex Graphic 35 Electric uses the Deckel “DKL” mount, which was used on other cameras like the Kodak Retina and Voigtländer Vitessa T, so if you’ve used one of those cameras, things should look pretty familiar here. Shutter speeds and f/stops are selected using a ring closest to the mount with two black “ears” which make gripping it easier. Both the shutter speeds and aperture rings are coupled together, so making a change to one makes an opposite change to the other so that the same EV value is maintained.

Like the Kodak Retina Reflex series, a wheel on the bottom of the shutter mount is used to select different combinations of EV values. If, for example, you had both 1/60 and f/8 selected, rotating the shutter speed ring to 1/30 would automatically select f/11, but if you wanted to select 1/60 and f/11, you’d need to turn this dial on the bottom to do that. I’ve always found these coupled EV systems to be extremely frustrating and slow to use, and making matters even more curious is the Graphic 35 Electric doesn’t display EV values anywhere on the camera. So you in essence have a coupled EV system, without EV numbers. Strange, but that’s how things were done back then.

Forward of the shutter speed and aperture rings is the focus scale which is turned by rotating the entire front lens group. Like other DKL lenses, the focus scale also has two red pointers which are coupled with the aperture ring. As a faster f/stop is selected, the two pointers get closer together to indicate narrower depth of field, as a smaller f/stop is selected, they spread apart to indicate greater depth of field. Although mechanically complex, this system works really well and was shared by a number of other lens makers such as Schneider and Zeiss.

Like other DKL mount cameras, removing the lens requires pressing in on a small metal tab directly below the lens mount and rotating the entire lens counterclockwise. A less than quarter turn is all that’s needed to remove the bayonet lens. Reinstalling a new lens is the opposite and doesn’t require that you press in this tab as it will lock into place automatically.

On the left side of the shutter is a large wheel which is used to set the film speed for the exposure meter. The wheel is split in half between a silver and black side, with small windows in the metal to indicate the selected speed. An unusually wide range of film speeds from ASA 8 to 8000 and DIN 10 to 40 are available, which is very surprising as finding films anywhere close to that fast did not exist in the era the camera was made.

Above the film speed windows is the front mounted shutter release button. The button is threaded for a cable release and is within easy reach of the photographer’s right hand while holding the camera.

The Graphic 35 Electric’s viewfinder is quite well featured, with silver 50mm and 135mm frame lines, with the entire image representing a 35mm frame. Both of the frame lines automatically correct for parallax, shifting down and toward the right at close focus. In the center is circular rangefinder patch which on this example is still very bright and contrasty, making accurate focus easy, even in poor lighting. Finally, above the main viewfinder is an image of the match needle so you can read the exposure with the camera to your eye. A neat feature of this match needle is that the needle itself glows, in addition to a triangular patch behind it, making it really easy to see.

In the image to the right, I struggled to capture a through the viewfinder image that shows both sets of frame lines, the rangefinder patch, and the match needle all at once, so I had to make a composite image that looks a little strange. In reality, seeing all these things is very easy and looks great. Unlike the frame lines and rangefinder patch which are illuminated with light from the front of the camera, the meter read out is illuminated from light coming through the top plate, so if the light isn’t consistent above and in front, one might be darker than the other.

My Results

Sadly, the Graflex Graphic 35 Electric was dead. No attempt at cleaning battery contacts, or checking soldering joints made any difference. I made a half hearted attempt to see if I could open up the camera, hoping to see some other loose connection that I could fix, but I eventually gave up, accepting this camera’s fate as a camera of the dead.

The camera might not work, but the 50mm f/2.8 Iloca-Culminar looked to be in great shape, both optically, and with an oil free diaphragm and clean glass. In a recent Camera of the Dead review, I was criticized that I shouldn’t be able to call it a review if I don’t actually shoot the camera so I thought that perhaps I could satisfy that person by mounting the DKL mount Iloca-Culimar to my Sony A7 II and firing off a few shots. Sure, it’s not the same as shooting the actual camera, but maybe I’d get a pass showing proof of what the lens is capable of.

As you might imagine, the digital images shot through the 50mm f/2.8 Iloca-Culminar look terrific. To be perfectly honest, I am not sure that there are any DKL mount lenses that look bad when adapted to digital. The biggest challenge when adapting these lenses is in the quality of the adapter. Where simpler adapters like for M42, Nikon F, or Minolta SR mounts are usually just solid pieces of metal, the DKL mount needs to have moving parts that control the diaphragm. Also, these adapters all seem to go beyond infinity focus at the expense of minimum focus, so don’t expect to shoot any close ups with them mounted.

Sharpness across the frame and color accuracy are excellent. I did notice a hint of lower contrast in the outdoor scenes, but that’s well within what you’d see from a digitally adapted rangefinder lens from the early 1960s. I would be happy to leave this lens on my camera all day long taking photos of the kids or pretty sunsets, and most people would be none the wiser. If there was one area in which I sort of detected a slightly unappealing look, it’s in the out of focus details. While I didn’t intentionally make any bokeh shots, looking at the images of the two road construction signs where the background is slightly blurred, the out of focus details appear to be erratic.

Had I shot this lens on film, it would have not been able to resolve as much detail as the Sony, but to know that it could, suggests that the limit of detail would be in the film, not the lens.

I don’t know that there’s much else I can tell you about the experience of just shooting the lens, as I would much rather have had a chance to hear and feel the sound of the electric motor.

If I had a working camera, I would have likely attempted to match Herbert Keppler’s claim that the camera could fire off 3 shots in 5 seconds. I probably would have agreed with his statement that the camera was very smooth, but also probably pretty noisy. I almost certainly would have complained about the ill-conceived EV wheel at the bottom of the lens and how I hated having to use it to decouple shutter speeds and f/stops.

More than likely I would have liked the quality of the images, and the convenience of the motor drive would have allowed me to forgive the exposure system, but I’ll likely never know as this one seems to be permanently dead and it’s unlikely I’ll come across another.

Hopefully that person who thought I can’t review a camera without shooting it will give me a pass on this one, as I did my best to show everything I possibly could of a very obscure camera that although having a very nice lens, had taken it’s last photo, likely decades before. If you have a working Graflex Graphic 35 Electric and would like to share your thoughts on it’s use, please let me know and who knows, maybe we can arrange a trade some day!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Iloca_Electric

http://phsc.ca/camera/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/GJ3-17.pdf

http://www.cjs-classic-cameras.co.uk/iloca/auto-electric.html

‘To be perfectly honest, I am not sure that there are any DKL mount lenses that look bad when adapted to digital’ hadn’t thought about it, but that certainly echoes my experience!

I can’t be sure, but did any other optical company other than German ones make lenses for the DKL mount? Certainly the Schneider lenses I have with my Retina III Reflex and the Voigtlanders for my Bessamatic de Luxe all work well adapted to digital.